Building an Earthwork Fort

Upcoming EventsView All

- Mar 17Sister Cities Committee Dundee and Helsingborg7:00 PM / Lloyd House

- Mar 18Historic Alexandria Resources Commission (HARC)7:00 PM / Lloyd House

- Mar 19Alexandria Archaeological Commission7:00 PM / Lloyd House

Museums

- Historic Alexandria (Home)

- Alexandria Archaeology Museum

- Alexandria Black History Museum

- Alexandria History Museum at The Lyceum

- Fort Ward Museum & Historic Site

- Freedom House Museum

- Friendship Firehouse Museum

- Gadsby's Tavern Museum

- Stabler-Leadbeater Apothecary Museum

- Visit Other Historic Sites

- African American History Division

- Alexandria Community Remembrance Project

- Alexandria Oral History Center

- Archives & Records Center

- Educational Resources

- Historic Preservation

- History of Alexandria

- Museum Collections

- News Releases

- Plan your Visit

- Rentals and Private Events

- Self-Guided Tours

- Stay Connected

- Support Historic Alexandria

Building an Earthwork Fort

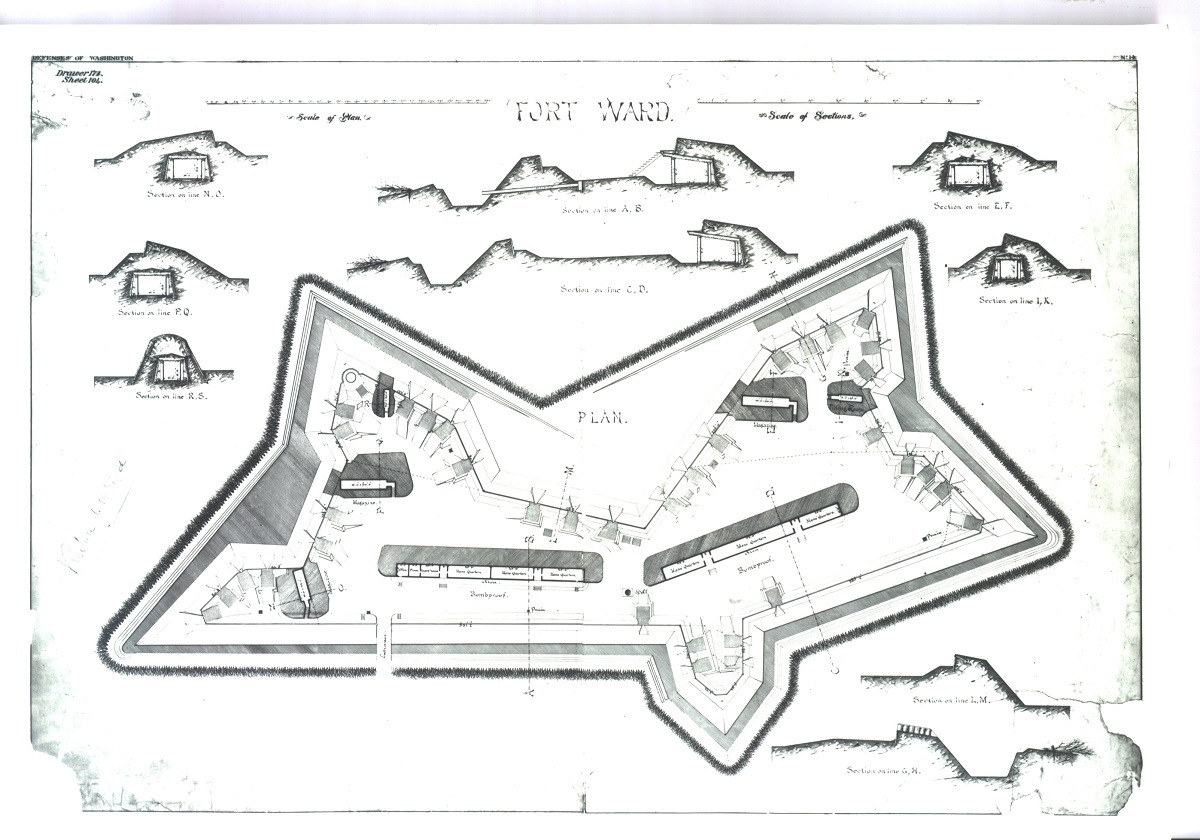

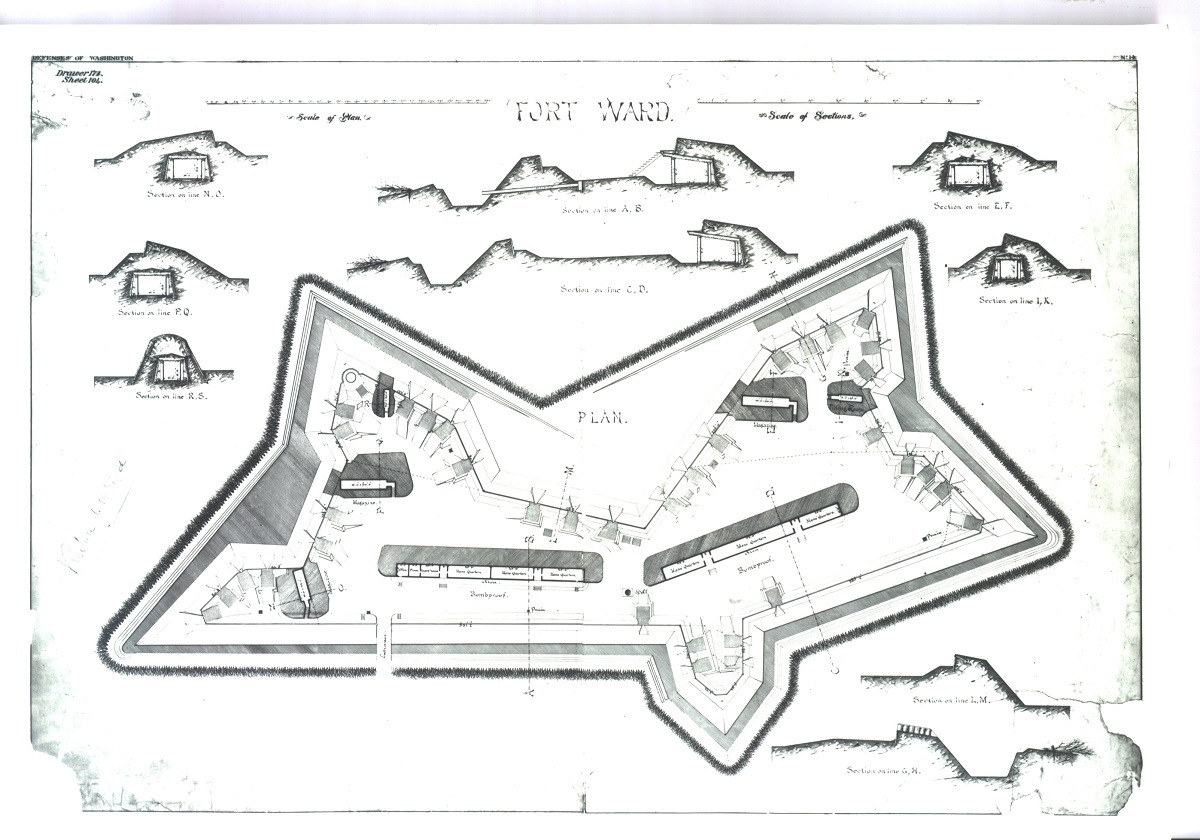

Nineteenth-century field fortifications or earthwork forts were constructed in various forms according to the topography of the land. They were constructed primarily from earth and wood, materials readily at hand, and were designed for temporary use. As this sketch illustrates, a framework was built, and as earth was removed from the "ditch" or dry moat that surrounded the fort, the earth was tamped (or rammed) into the framework. As the ditch grew deeper, the wall grew higher, extending to heights of 20-25 feet. The completed walls were 12-18 feet thick and were supported by a vertical pole system called "revetment."

Dennis Hart Mahan, professor of civil and military engineering at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, was primarily, if not solely, responsible for the theories of defensive warfare used by the Union and Confederacy during the American Civil War. Mahan taught the theories of military science developed in France by Marshal Prestre de Vauban, adapting Vauban’s principles to his own ideas of the changing nature of warfare. Mahan’s Complete Treatise of Field Fortifications (1836) and his Elementary Treatise of Advance-Guard, Outpost and Detachment Service of Troops (1847) were in use by army officers before the Civil War and became standard reference works for men who would lead armies for both the Union and Confederacy. Considered the nation’s leading military educator, Mahan would remain at the U.S. Military Academy during the Civil War as his theories were employed in every aspect of land warfare. Nowhere are Mahan’s theories on defensive warfare more visible than in General John G. Barnard’s design and construction of the Defenses of Washington.

Parts of the Fort

See a full-size image of the map shown above.

East Bastion: This Bastion protected the rear wall of the fort from the Ceremonial Gate to the North Bastion. Jutting out from the earthen walls with four strategically placed guns, the East Bastion protected the entire area behind the fort where the officers’ quarters, barracks and mess hall were located.

North Bastion: The North Bastion’s guns were positioned to cover one of the major routes into Alexandria (Leesburg Turnpike) as well as provide protection for an outlying rifle trench. The rifle trench extended from the point of the North Bastion to Battery Garesche, the next fort in line, about two miles away.

Northwest Bastion: The Northwest Bastion, together with its counterpart the Southwest Bastion, were the major defensive elements of Fort Ward. Armed with two 24-pounder Howitzers, three 4.5" ordnance rifles and a six-pounder James rifle, the Northwest Bastion guarded the approach to Alexandria along the Leesburg Turnpike (State Route 7).

South Bastion: Guns in the South Bastion were mounted to cover the ditch along the wall of the Southwest Bastion.

Southwest Bastion: The largest gun in the fort, a 100-pounder Parrott rifle, was mounted en barbette on a center pintle carriage at the point of the Southwest Bastion. This weapon had a maximum range of five miles and the center pintle carriage enabled the gun to be aimed in any direction, providing a significant range of fire to guard the approach to Alexandria via Little River Turnpike (State Route 236).

Rifle Trench: Rifle trenches were dug with earth piled to the exposed (defensive) side into which infantry could move without exposure to enemy fire. These trenches connected many of the forts in the Defenses of Washington to prevent an advancing enemy from executing a flanking maneuver to the rear of the forts.

Abatis: An abatis was constructed from the branches of large trees piled several feet high in a line along the outer wall of the ditch (dry moat). The ends of the branches pointing outward were cut to a point to deter enemy troops from breaching the line. An abatis usually surrounded the entire perimeter of the fort, having the same effect as barbed wire.

Bombproofs: These partially underground structures were located in the center of the fort. Designed to provide space for operations in the event a fort came under attack, the bombproof could hold one third of the fort’s complement of troops. Space was also allocated for a guard house and dispensary. Covered by several feet of earth, a breastheight and banquette were also constructed on top of the bombproof as a line of defense for infantry in any attempt to breach the fort’s walls.

Powder Magazine and Filling Room: Ammunition for the fort’s guns was kept in underground storage facilities called powder magazines and filling rooms. Shells were armed and sometimes stored in the filling room, while the magazine was used to hold black powder and crated rounds. Implements for firing the cannons could also be kept in the filling room.

Officers’ Quarters and Barracks: The garrison for a fort lived outside the earthen structure. The officers’ quarters, barracks and mess hall as well as other support buildings were located to the rear of the fort. In an attack, the troops would have moved inside the earthen structure, closing the gate.

Ceremonial Gate: The large Ceremonial Gate was erected in 1865 to mark the main entrance to Fort Ward. The arch was adorned with a castle, the insignia of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which designed and supervised the construction of the fort. The gate’s columns were topped with a stand of cannon balls in tribute to the artillerymen who manned the fort from 1861-1865. This gate, which marks the site of the original structure, has been reproduced from a Corps of Engineers drawing for Fort Ward.

Glossary of Military Terms

Abatis (Ah-ba-tee): A barrier of felled trees with sharpened and entangled branches pointing toward the enemy and lined up in a mass along the glacis. The abatis served to impede the enemy advance upon the fort.

Banquette (baun-kett): The narrow walk behind the breastheight or interior slope on which the infantry stands while firing. The flat walk is the banquette tread; the slope up to it is the banquette slope.

Barbette: Raising a gun by placing it on a high carriage or mound of earth so that it fires over the parapet rather than through an opening in the wall, expanding its range of fire.

Bastioned fort: A fortification plan which assures that every section of the fort is mutually supported by fire from another part. The star-shaped fort with five or more bastions is considered the ideal fort and is generally used only for important works.

Breastheight or interior slope: The inside of the fort wall (parapet) where the defender leans while firing.

Counterscarp: The outer slope of the ditch (dry moat), opposite the parapet.

Ditch: A deep dry moat surrounding the fort in front of the parapet. It is designed to impede access to the parapet.

Embrasure: An opening in the parapet (fort wall) through which a gun is fired. Although it weakens the parapet to assault, the embrasure provides protection for the gun crew.

Emplacement: see Embrasure.

Exterior slope: That part of the parapet facing toward the enemy.

Filling room: An underground structure like a powder magazine where rounds were armed and loose powder, shot and firing implements were kept.

Flanking maneuver: The movement of troops around an enemy or his works in an effort to get behind and cut off any possibility of escape. In a defensive system like the forts that surrounded Washington, D.C., rifle trenches and outlying gun batteries constructed between the forts all but eliminated the possibility of such a movement.

Gabion (gay-bee-un): A round, wicker cylinder, approximately 24" in diameter and 3' high, filled with sod. Gabions were used to line gun embrasures and could be used for other purposes like supporting the walls of a temporary fortification.

Garrison: The troops stationed at a fort or other military stronghold.

Glacis (gla-see): The raised ground in front of the ditch, which exposes the enemy to the defenders' fire.

Interior slope: see Breastheight.

Ordnance: Military weapons, ammunition and equipment.

Parade ground: The flat area in the center of the fort.

Parapet: An elevated wall or embankment constructed from earth, wood or stone designed to intercept enemy fire.

Powder magazine: An underground structure where containerized rounds and black powder for the ordnance of a fort were kept.

Profile: A vertical cross-section of the fort.

Revetment: Material such as blocks of sod, trunks of small trees (pole revetting), or horizontally placed boards used to support the earthen walls on the interior of a field fortification. Pole revetting was the preferred choice.

Rifle trench: A deep ditch with excavated earth piled along the exposed side that protected infantry from enemy fire and enabled them to prevent a flanking maneuver on the fort or battery.

Scarp: The inner slope of the ditch (or moat) that surrounds a fort; the same as the exterior slope.

Superior slope: The top of the parapet.

Trace: The ground-plan or outline of the fort.

Terreplein (ter-a-plane): The flat ground inside the fort, at least 6'6" below the top of the parapet.

Traverse: A breastheight placed on top of the magazine, bombproof or filling room to form a second line of defense, usually accessed by a ladder or steps.