Soil Collection Remembrance Event

Soil Collection Remembrance Event

Soil Collection Remembrance Event

September 24, 2022 at 4 p.m.

Market Square, 301 King Street

The Alexandria Community Remembrance Project will hold a ceremony to memorialize the lives and deaths of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas who were lynched in this City on April 23, 1897, and August 8, 1899.

These lynchings and the events that followed traumatized Black Alexandrians, yet they were struck from our collective history as though they never occurred. The Equal Justice Initiative's Remembrance program asks participating projects to hold Soil Collection Ceremonies.

The rituals encourage participants to create a visual memorial for the victims by gathering soil.

On Saturday, September 24, 2022, Alexandrians are invited to a Soil Collection Ceremony at Market Square at 4 p.m. where participants will have an opportunity to touch earth excavated from sites known intimately by McCoy and Thomas. Two wooden vessels designed and built by students at Jefferson-Houston IB School will hold the soil representing the lives of each man. Participants will take some of this soil and place it into a glass jar bearing each man’s name that will be delivered by the Alexandria community to the Equal Justice Initiative on October 7, 2022.

‘This Soil Cries Out. ’Ceremony remembers lynching victims McCoy, Thomas. Alexandria Gazette Packet, September 29, 2002

Soil Collection Ceremony honors victims. Alexandria Times, September 29, 2022

Remembering the lost lives of Alexandria’s lynching victims Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas. Alexandria Times, September 22, 2022

With scoop by scoop of soil, Alexandria remembers lynched Black teens. Washington Post, September 27, 2022

View the Event

Event Program

Alexandria Community Remembrance Project Soil Collection Ceremony

Honoring Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas

Download or print the Event Program

A Call to Gather Musical Invitation

- “Precious Lord,” by Thomas A. Dorsey. Min. Siera Grace

Welcome and Recognitions & Proclamation. Mayor Justin Wilson

Intention and Purpose. Gretchen Bulova and Audrey Davis, Co-Directors ACRP

Narratives. Alexandria City High School Students

- Joseph McCoy. Irvin (Naeem) Scott

- Benjamin Thomas. Nathan Desta

The Earth Speaks. Zeina Azzam, City of Alexandria Poet Laureate

Blessing of the Soil

- For Joseph McCoy. Rev. James Daniely of Roberts Memorial United Methodist Church

- For Benjamin Thomas. Pastor Octavia Caldwell of Shiloh Baptist Church

Libation Ritual. Rev. Quardricos Driskell of Beulah Baptist Church

Recognition of Descendants. Rev. Quardricos Driskell of Beulah Baptist Church

Invitation to Collect the Soil. Rev. Quardricos Driskell of Beulah Baptist Church

Please form a line at the outer end of each row of seats. Those on Joseph McCoy’s side stay on the outside of the vessels and those on Benjamin Thomas side move along the inside of the vessels. Please extract a small amount of soil from inside of each vessel with your hands or the trowel and place it into the jar before moving to the next vessel and doing the same before carrying on to your seat. Thank you for participating.

Music for Meditation. Vivian Podgainy, Cellist

Interfaith Reading of Lift Every Voice and Sing, by James W. Johnson/J. Rosamond Johnson

- Pastor Octavia Caldwell for Shiloh Baptist Church

- Rev. Stacy Carlson Kelly for St. Paul’s Episcopal Church

- Rev. Dr. Robert Melone for Mount Vernon Presbyterian Church

- Rev. Robin Anderson for Commonwealth Baptist Church

- Rev. Marcia Norfleet for Alfred Street Baptist Church

- Rev. Dr. Barbara La Toison for Alleyne AME Zion

- Kimberly Young for Washington Street United Methodist Church

- Rev. Collins Asonye for Meade Episcopal Church

- Rev. Grace Han for Trinity United Methodist Church

- Rabbi David Spinrad for Bethel El Hebrew Congregation

- Rev. Dr. James G. Daniely for Roberts Memorial United Methodist Church

- Rev. Dr. Noelle York Simmons for Christ Church Episcopal

- Rev. Dr. Barbara La Toison for Alleyne AME Zion

- Rev. Peter J. Clem for the Basilica of St. Mary

- Rev. Donald Fest for St. Joseph's Catholic Church

- Rev. Quardricos Driskell for Beulah Baptist Church

“Still, I Rise,” by Yolanda Adams. Min. Siera Grace

The Black National Anthem: "Lift Every Voice and Sing"

The Negro National Anthem: "Lift Every Voice and Sing"

by James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871 - June 26, 1938)

This poem was originally written by Johnson in celebration of the birthday of Abraham Lincoln and was performed by children in Jacksonville, Florida. In church hymnals it can be found with the title “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Over the years, the song was popularized as The Negro National Anthem and figures prominently in African American culture, yet it is not well known among white people of European descent. Learn more.

Today, in a spirit of reconciliation, an interfaith group of ministers will join together in the reading of the poem during the collection of the soil for Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas.

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us,

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun Let us march on till victory is won.

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

We have come over a way that with tears have been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

Out from the gloomy past,

Till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who has brought us thus far on the way;

Thou who has by Thy might Led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places,

Our God, where we met Thee;

Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee;

Shadowed beneath Thy hand,

May we forever stand.

True to our GOD,

True to our native land.

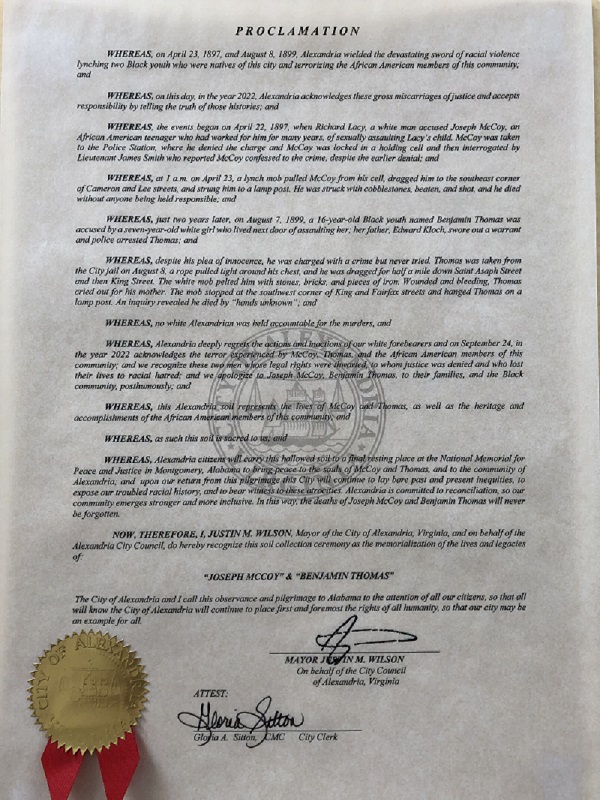

A Proclamation

The Proclamation

Whereas, on April 23, 1897, and August 8, 1899, Alexandria wielded the devastating sword of racial violence lynching two Black youth who were natives of this city and terrorizing the African American members of this community; and

Whereas, on this day, in the year 2022, Alexandria acknowledges these gross miscarriages of justice and accepts responsibility by telling the truth of those histories; and

Whereas, the events began on April 22, 1897, when Richard Lacy, a white man accused Joseph McCoy, an African American teenager who had worked for him for many years, of sexually assaulting Lacy’s child. McCoy was taken to the police station, where he denied the charge and McCoy was locked in a holding cell and then interrogated by Lieutenant James Smith who reported McCoy confessed to the crime, despite the earlier denial; and

Whereas, at 1 a.m. on April 23, a lynch mob pulled McCoy from his cell, dragged him to the southeast corner of Cameron and Lee Streets, and strung him to a lamp post. He was struck with cobblestones, beaten, and shot and he died without anyone being held responsible; and

Whereas, just two years later, on August 7, 1899, a 16-year-old Black youth named Benjamin Thomas was accused by a seven-year-old white girl who lived next door of assaulting her, her father, Edward Kloch, swore out a warrant and police arrested Thomas; and

Whereas, despite his plea of innocence, he was charged with a crime but never tried. Thomas was taken from the City Jail on August 8, a rope pulled tight around his chest, and he was dragged for half a mile down Saint Asaph Street and then King Street. The white mob pelted him with stones, bricks, and pieces of iron. Wounded and bleeding, Thomas cried out for his mother. The mob stopped at the southwest corner of King and Fairfax Streets and hanged Thomas on a lamp post. An inquiry revealed he died by “hands unknown;” and

Whereas, no white Alexandrian was held accountable for the murders, and

Whereas, Alexandria deeply regrets the actions and inactions of our white forebearers and on September 24, in the year 2022, acknowledges the terror experienced by McCoy, Thomas, and the African American members of this community; and we recognize these two men whose legal rights were thwarted, to whom justice was denied and who lost their lives to racial hatred; and we apologize to Joseph McCoy, Benjamin Thomas, to their families, and the Black community, posthumously; and

Whereas, this Alexandria soil represents the lives of McCoy and Thomas, as well as the heritages and accomplishments of the African American members of the community; and

Whereas, as such this soil is sacred to us, and

Whereas, Alexandria citizens will carry this hollowed soil to a final resting place at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama to bring peace to the souls of McCoy and Thomas, and to the community of Alexandria; and upon our return from the pilgrimage this City will continue to lay bare past and present inequities, to expose our troubled racial history, and to bear witness to these atrocities. Alexandria is committed to reconciliation, so our community emerges stronger and more inclusive. In this way, the deaths of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas will never be forgotten.

Now, Therefore, I, Justin M. Wilson, Mayor of the City of Alexandria, Virginia, and on behalf of the Alexandria City Council do hereby recognize this soil collection ceremony as the memorialization of the lives and legacies of:

Joseph McCoy & Benjamin Thomas

The City of Alexandria and I call this observance and pilgrimage to Alabama to the attention of all our citizens, so that all will know the City of Alexandria will continue to place first and foremost the rights of all humanity, so that our city may be an example for all.

MAYOR JUSTIN M. WILSON

On behalf of the City Council

of Alexandria, Virginia

A Poem: The Earth Speaks

The Earth Speaks:

Honoring the Lives of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas

© Zeina Azzam, Poet Laureate of the City of Alexandria, Virginia, August 2022

The earth speaks.

Listen to the stories

from beneath our feet.

Gather the soil, touch it, smell it,

reply with your breath

and heart.

This hallowed ground

witnessed despicable deeds.

It cries in pain.

Let us open our ears to hear

the mobs, fists, whips, guns, and chains.

Let us comprehend the horror

of the noose on the lamppost.

We must look back

to sense the wounds and grief,

the wrongs inflicted

on the agonized and the aggrieved.

At the same time

we ask this soil to teach us

about where our ancestors

walked and worked and loved,

the places they learned and played,

slept and ate and prayed,

held weddings and baptisms

and communal celebrations.

They honored the living and the dead,

protected and uplifted each other

with love and kindness.

This earth tells vital stories.

We feel the deep foundation

gripping the stones we walk on,

the roots of the struggle for freedom

that keep trying to reach upward

to emerge and grow, until today.

We are still learning to make way

for rays of light

to nourish them.

As we cup this sacred soil in our hands,

we become grounded in history,

surrounded by messages from the earth

and blessings from the sky

to keep listening—

like rain on an autumn day

as it touches everything:

our schools, homes, neighborhoods,

the river and the trees,

these tangible memories of Joseph and Benjamin,

and the earth

that continues

to speak.

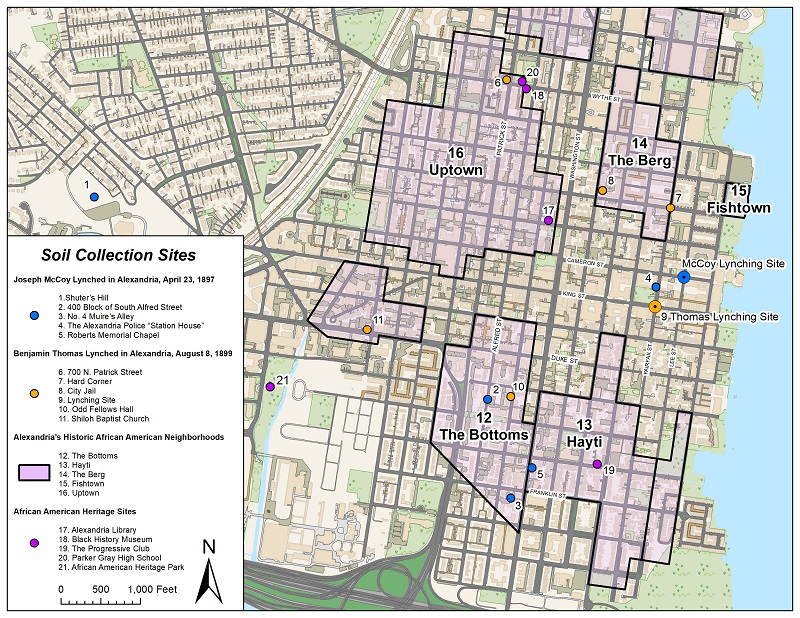

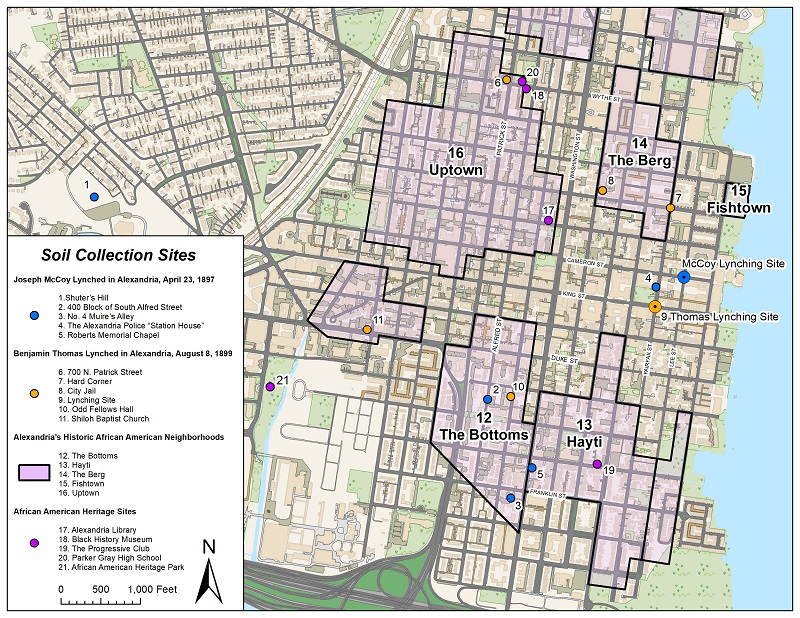

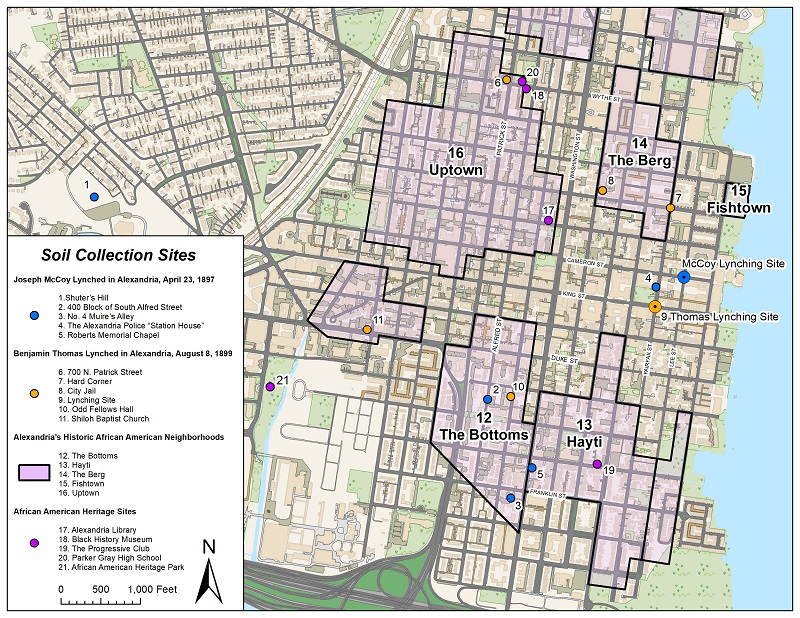

Soil Collection Sites

To honor the lives of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas who were terrorized by racial violence soil has been collected from areas in the City of Alexandria associated with both men's lives, arrests, and deaths. This was combined with soil from areas of historical significance to the African American community.

Over the summer, a team of Alexandria City Archeologists and ACRP members reviewed sites recommended by the Soil and Marker Committee. In August, the soil was excavated from as many of these locations as possible.

Read the narratives of McCoy and Thomas as well as descriptions of the locations where soil was gathered and match them up with the map of Alexandria.

In Memoriam: Joseph McCoy April 23, 1897

Joseph McCoy Narrative

Joseph McCoy

April 23, 1897

One-hundred-and-twenty-five years ago, on a mild April evening in 1897, a doctor told Richard Lacy his 8-year-old daughter had been “tampered with” and set in motion a series of events that ended with the brutal lynching of Joseph McCoy.

When Lacy discovered his daughter had been sexually assaulted, he blamed the 18-year-old Black youth he had known and had employed since a child. A neighbor who found Lacy searching for McCoy became concerned he might kill the boy and told police about the alleged crime.

Two stories of McCoy’s arrest emerged, one placed him at Lacy’s home still working at 7PM, while the other claimed he was arrested at his Aunt Rachel’s house at 4 Muire’s Alley (about three blocks North of Lacy’s property at Church and Washington Streets). [3]

The morning edition of The Washington Times, printed the night before the lynching, carried the following story of the arrest:

“When the horrible truth was discovered this evening, the father immediately went in search of McCoy, and would doubtless have killed the negro had he been able to find him at that time. The occurrence was reported to police headquarters about 7 o’clock, and Lieut. Smith went immediately in search of the negro. He found McCoy at the home of his aunt, in Muire’s Alley, near the scene of his brutal crime. As soon as Mr. Lacy learned that the negro had been captured, he became greatly excited and ran to his home evidently with the intention of securing a revolver. The officer in the meantime hurried to the police station with his prisoner,” The Washington Times, April 23, 1897.

The other arrest story published in afternoon newspapers and retold by Lieut. James Smith during a Governor’s inquiry into the lynching of McCoy, stated that Smith went to the Lacy residence to find McCoy before the enraged father did. Smith said he asked McCoy to come to the police station with him but did not tell the young man he was under arrest until they arrived there.

The Times initial account is more likely to reflect actual events since in the aftermath of the lynching authorities colluded to provide a version of events that would protect the identities of those who murdered McCoy.

Once they were at the station, Smith invited City Councilman and Newspaperman John Strider into the Chief of Police’s empty office while he interrogated McCoy. [4]

According to all accounts, Joseph “flatly” denied the allegations made against him, however, after what was described as “a little persuasion” McCoy “broke down and acknowledged that he was guilty of the crime charged against him.”

News of the crime and McCoy’s arrest spread throughout the city igniting a racist fury that brought more than 150 white men to the police station just after 11 PM. Eager to met out their own justice, the mob asked officers to hand McCoy over to them, but the police refused.[4]

Using a battering ram lifted from a nearby lumber yard the mob broke through the police station doors. Lacy was among them. Officers managed to repel the lynch mob, arrest the ring leaders, and secure the entrance with the same timber used to break in. [4]

Around 12:15AM the police sent word of the attempted lynching to Mayor Luther Thompson. It was within Thompson’s power to summon the largest military company in the state to defend the rule of law, he also could have moved McCoy to a new location or added more police to protect him. Instead, the mayor told police to free the leaders of the attack and then he went back to bed. [4]

At 1:00AM, by all accounts, at least 500 people were outside the station house. Within the crowd were leading citizens and members of the militia. The white mob surged forward, smashing shutters, chopping window sashes, hacking at the building with axes, sledges, crowbars, and picks. They dragged Joseph into the street where he begged for his life. They force marched him to the intersection of Cameron and Lee Streets and hanged him from a streetlamp on the southeast corner. Joseph’s neck didn’t break. They beat him with fists, clubs, and cobblestones then shot him three times. In the first hour of Friday, April 24, 1897, Joseph McCoy died because he could not breathe.

Hours later, Alexandria’s white leaders realized they were being scrutinized when Virginia Governor Charles O’Ferrall, a law-and-order Democrat who crusaded against mobocracy and lynchings, sent a telegram to Alexandria’s Judge J.K.M Norton. In it he asked why the Alexandria Light Infantry (ALI) had not mobilized and said he wanted a detailed account of what happened and where the fault lay.

“Please wire me the facts briefly and follow with letter in case of lynching in your city this morning. It seems most irregular to me that in Alexandria with police force and strong military company such a thing should occur. Where rests the blame? Is it with the Civil officers or military?”

To hide the identities of the lynchers, the ineptitude of police, and to explain the failure of the ALI to mobilize, Mayor and Gazette reporter L. Thompson, Councilman and Times reporter J. Strider, Commonwealth Attorney Leonard Marbury, ALI Capt. Albert Bryan, and the police developed a new narrative about the detention and lynching of McCoy.

In the end, no one was held accountable for Joseph’s death or for the days of triumphalism and nights of terror that followed.

However, Alexandria’s African Americans did not forget these grave events, and two years later, when another Black youth was accused of sexually assaulting a little white girl, they tried to defend the accused and they vehemently protested mob law in the weeks, months and years that followed.

This narrative for Joseph McCoy was written by Tiffany Pache, ACRP Coordinator, and is based upon newspaper accounts, court records, and the research report produced by ACRP’s volunteer research committee that can be read on the ACRP website.

Eulogy for Joseph McCoy

Remarks by Rev. James Daniely of Roberts Memorial United Methodist Church, the church that held Joseph McCoy’s funeral service in 1897.

Joseph McCoy Eulogy

April 23, 2022

Psalm 137: 4: How can we sing the songs of the LORD while in a foreign land?

From the time Africans came as indentured/enslaved people around 1619, we have caught hell. Arriving with the Dutch to New Amsterdam, later called New York, some were manumitted by 1644 and many others were granted full manumission in 1827, but only in New York. Yet still what does it mean to be granted your freedom? If granted, then it may be taken away! But did not the founding fathers grant freedom to all? The Declaration of Independence states: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” But they didn’t Africans! In fact, in 1857, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, declared, on behalf of the majority decision…” blacks have no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.” Is this carte blanch to do with blacks as any white person so determined? If so, a very dangerous scenario was alive in the land. How dangerous? Between 1890 and 1900, more than 1600 blacks were lynched by white mobs all over this socalled bastion of freedom! In fact, history tells us that were nearly 5,000 black victims of brutality in that era, the post Reconstruction era, by white mobs bent on “keeping the darkies in their place”. No wonder the protest song by Billy Holiday, “Strange Fruit”, caught the imagination of blacks and angered white audiences as it was barred from radio broadcast, highlighting so-called ‘lynching era (1890-1940).

The House of Representatives did manage to put forth an Anti-Lynching bill in 1922, but President Warren G. Harding refused to push the matter before the US Senate. (A footnote: the Emmett Till Antilynching Act was finalized as a Federal law March 29, 2022. A little late, don’t you think?)

Alexandria was not an exception to this vehement violence; in fact, we gather today to remember Joseph McCoy, another victim of the insanity which swept these shores. This is not to say that lawlessness ruled the land. What it does say is that there were many silent witnesses who either said nothing or did nothing to aid the victims. But there were also organized lynchings where newspapers advertised the upcoming events. And though images within the crowd were printed in local newsprint, law enforcement never could “identify anyone committing this heinous crime.

To see an injustice and not attempt to prevent it gives credence to the act. So where was the outcry? So, we turn to James Russell Lowell, writing during the stench of slavery in America. His epic poem speaks volumes against the injustices facing African Americans. However, he was in the minority and his words appear to have fallen on deaf ears:

Careless seems the great Avenger; history's pages but record One death-grapple in the darkness 'twixt old systems and the Word; Truth forever on the scaffold, Wrong forever on the throne, —

Yet that scaffold sways the future, and, behind the dim unknown, Standeth God within the shadow, keeping watch above his own. Then to side with Truth is noble when we share her wretched crust, ere her cause bring fame and profit, and 'tis prosperous to be just; Then it is the brave man chooses, while the coward stands aside, doubting in his abject spirit, till his Lord is crucified, and the multitude make virtue of the faith they had denied.

-James Russell Lowell 1819-1891.

He appears to declare that God was standing by, watching to see if any would side with Truth. Those in power didn’t. Were they either cowards or timid politicians to afraid to act on the side of Truth? Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., speaking against in another context, gives me a clear perspective on the matter:

“Cowardice asks the question, is it safe? Expediency asks the question, is it politic? Vanity asks the question, is it popular? But conscience asks the question, is it right? And there comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe, nor politic, nor popular, but one must take it because it is right.”

So, the text before us comes at a time when Israel has been taken captive by the Babylonians. The psalmist is devastated by the chain of events. His beloved Jerusalem has been destroyed and the leaders have either been killed or taken into captivity. He knows firsthand of the atrocities his people have suffered and in prayer, asks for vengeance. He wants the Babylonians to suffer like he has suffered. Can I blame him? No, because it is righteous indignation. But is it right? You tell me!

As I stand before you today, I am appalled that more than a century has passed since 19-year-old Joseph McCoy was murdered and we’re just getting around to passing legislature making it a crime. It might make one ask, is this too little, too late? He was arrested without a warrant, dragged from his cell by a mob (over 500 persons says the Evening Star) and shot multiple times, and finally, brutally lynched at the corner of Cameron and Lee streets. By the time an autopsy was performed, his head had been split open by an axe, and his body showed evidence of burn marks! What type of humans does this to another human?

His family refused to claim the body. A report from the Evening Star (dated April 26, 1897, states that an aunt said: “As the people killed him, let them bury him”. Accused of attacking a child of Richard Lacy, whom he worked for, he never had a trial by his peers. Oh, yeah, I forgot, “blacks have no rights which the white man was bound to respect…”

What’s a minister to say at a time like this? The original eulogist, the Rev. William H. Gaines, pastor of Roberts Chapel, said: “Those who shed blood shall lose their own” Then, carefully, he added, “Mothers, take your sons into your confidence and teach them the higher principles of morality, that there might never again be a repetition of the terrible crimes committed and charged to have been committed.”

Hear him clearly, ‘that there might never again be a repetition of the terrible crimes’, my emphasis. I don’t think the twenty black persons in attendance missed what was being said. They were brave souls to attend, and I am certain they heard, what happened to this young man should never, ever happen again. As a follower of Jesus, the Christ, I agree that it should never, ever, happen again.

We must remember every atrocity; every dastardly deed perpetrated against humankind by humankind and find a way to forgive. In that forgiveness however is a determination to prevent them from happening again. In my resolve to fight injustice in every form, the words of the Apostle Paul help me in that regard: “Therefore, my beloved, be steadfast, immovable, always excelling in the work of the Lord, because you know that in the Lord your labor is not in vain.” (I Corinthians 4 15:58). And this is the Lord’s work, laboring to make equal justice the law of the land. It’s the Lord’s work, bringing equity and healing to our land. We must be diligent, steadfast, and immovable in our stance against police violence against brown and black people! Equally adamant against politicians taking the expedient path in writing the nations statutes, as opposed to the right laws! But that’s not all, each of us must wrap ourselves in the concepts of holiness espoused through the Abrahamic Traditions: love of neighbor, charity for the poor, and justice for all! Those traditions include Judaism, Christianity, Islam, the Baha’i Faith, Druze, Samaritan, and Rastafari. Our task, those gathered here and those viewing/seeing this presentation, must be to become people on a mission to right all the wrongs in our society. To become the peacemakers during confrontations of hate. To make this American nightmare into the reality where all men and women in these United States are treated as equals, that they are protected by their governments to ensure their Rights, that among these are equal access to good representation, an opportunity to be trained for gainful employment, access to good health care, and education. Then, Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness has the same meaning to the sisters and brothers in the Burg as well as Beverly Hills and Chirilagua!” And that we will, by any means necessary, protect this grand thought and make it a reality for all of us. And all is one of those inclusive terms that leaves no one out! It’s not enough to hold others accountable, we, each of us, must be accountable to each other because we are our brother and sister’s keepers.

And to answer the question: How can we sing the songs of the Lord while in a foreign land? A land that devalues, belittles, and devours it’s brown and black citizenry…by not doing it alone. We must walk with Jesus…the song writer said,” I’ve seen lightning flashing, I’ve heard thunder the roll; I’ve felt sin’s breaker dashing, trying to conquer my soul; I’ve heard the voice of Jesus, telling me still to fight on; He promised never to leave me, never to leave me alone. No, never alone, no never alone. He promised never to leave me alone!” That’s my story and I am sticking to it! Amen.

Poem in Honor of Joseph McCoy: To Bring Justice Near (2022)

To Bring Justice Near -- a poem for Joseph McCoy

On the Commemoration of the Lynching of Joseph McCoy in Alexandria, Virginia, on April 23, 1897

© Zeina Azzam, Poet Laureate of the City of Alexandria, Virginia, April 23, 2022

A Black man was lynched in our city, here,

where a white mob savagely had its way.

We must face history, bring justice near.

He lived on Alfred Street, age eighteen years,

grew up when harsh Jim Crow laws ruled the day.

A Black man was lynched in our city, here.

Together let’s say his name, bare our tears.

We lift up Joseph McCoy, and we pray:

We must face history, bring justice near.

The trauma from racial hate is severe,

remains till now, unless we change our ways.

A Black man was lynched in our city, here.

No one was tried for his murder; it’s clear

that this son of our city was betrayed.

We must face history, bring justice near.

Let’s educate our youth, open eyes, ears,

so inhumanity is not replayed.

A Black man was lynched in our city, here.

We must face history, bring justice near.

Poem in Honor of Joseph McCoy: Feeling in Blanks (2020)

Feeling in Blanks ... For Joseph McCoy

© KaNikki Jakarta, Poet Laureate of Alexandria, Virginia April 17, 2020

Black Boy

Born to Ann and Samuel as Reconstruction ended

And the era of Jim Crow started

Left many family members broken hearted

Before his life as a man officially began

A sorrowful trend amongst black families

Tugging on heart strings to rejoice or weep

when black boys are birthed

A blessing and a curse on a family tree

Because we’re never sure if someone will kill you

And write you down in history untrue

After accusing you of crimes like

Assaulting someone white

Talking back to someone white

Looking at someone white

Whistling at someone white

Despite putting up a fight or screaming a denial

You might get a trial

But it will be unjust

Although you initially denied it all

I think you thought it was best to confess…

This is not a history that belongs to you alone

And if you would have grown

Just a bit older

You may have cried on someone’s shoulder

Two years later over another black boy named Benjamin Thompson

Who shares this story too

I wish I could talk to you

I would ask you what really took place

I wish I could look upon your face

to hear your story

The way that you would have it told

The way that circumstances would unfold

On April 23, 1897

Truth is, I want to pen your story

But the newspapers don’t show

What happened all of those years ago

But this is what I know…

You were born Joseph McCoy

You had four siblings and you were the youngest boy

And before you were ever thought to be

Your grandmother Cecilia McCoy was born free

More than a half century

Before you were lynched

Hanged from a lamppost and shot multiple times

No family members would claim your body

And no one was ever charged with a crime

But, this is not the part of your story that I would want to tell

I don’t want to recap the horrible night a mob of 500 retrieved you from jail

I don’t want to write about your how your funeral was held

Instead,

I would like to highlight

That despite the fact you didn’t celebrate your 21st birthday

Today,

123 Years Later

You are celebrated

You are remembered

A legend, a light

Shining bright

even in your absence

An ancestor whose story far surpassed the details of your death

A part of history that will let in peace be the way you rest

No one remembers the names of the people who took your life

They don’t get glory for spreading bitterness and strife

But you

Joseph McCoy

A black boy

Born to Ann and Samuel as Reconstruction ended

And the era of Jim Crow started

Whose death left many family members broken hearted

Before his life as a man officially began

A horrific trend

In black history

Another tragedy

But your history will be one remembered alongside

Others who were also lynched, shot, or hanged

But we will remember your name

Because your history is within my pen now

Within my words now

A black writer

Who decided to write about you in a positive way

But still today

We are left with the question

Who could you have grown to be?

If they would not have killed you

Soil was collected from Joseph McCoy’s boyhood home on S. Alfred Street, the place of his arrest at 4 Muire’s Alley, from outside the Police Station House on the East side of City Hall where he was taken by a lynch mob, and from his home church. This soil was combined with samples from sites of significance to local African American history and placed in a vessel engraved with McCoy’s name. Students at Jefferson-Houston IB K-8 School led by their technical education instructor Nicole Reidinger designed and built the vessel.

1. Shuter's Hill

As early as 3000 BCE, Native Americans camped on this site during hunting and fishing expeditions. A wealthy white merchant and slave owner named John Mills was the first person to establish a plantation house on the property in the early 1780s. Enslaved men and women lived and worked on the property for Mills, and for later owners of the land in the 19th century. Archeologists have identified the foundations of six buildings on the property, many of which were occupied by the enslaved workforce, making this one of the few places in Alexandria where so many artifacts related directly to households of enslaved Americans have been discovered. One of the buildings uncovered at Shuter’s Hill served as a laundry, a place where enslaved washer women cleaned, mended, and sewed clothing. The finding is an additional link to McCoy’s story, since his grandmother who raised him spent her life working as a laundress in Alexandria.

2. 400 Block of South Alfred Street

Joseph McCoy was raised in The Bottoms neighborhood of Alexandria by his grandmother Cecelia McCoy. The 1880 Census showed that Cecelia and one-year old Joseph, lived at 491 S. Alfred Street. Today, the Heritage at Old Town apartments span the length of the block across from where the McCoy home once stood.

3. No. 4 Muire’s Alley

In February 1897, Rachel Chase, who was related to Joseph McCoy, married Samuel Gairy (sometimes spelled Gary or Geary) and lived at Number 4 Muire’s Alley, located just behind 714 Franklin Street. It is likely that McCoy was at Rachel and Samuel’s house when he was arrested.

4. The Alexandria Police “Station House”

The Station House was located at 126 N. Fairfax Street on the east side of City Hall. Today, you can still see the words etched above what was an entrance with double doors. Joseph McCoy spent his last hours alive in a cell in this building. This is where he reportedly confessed to criminal assault against Lacy’s daughter and where a white mob twice attacked the building before apprehending McCoy and dragging him to the corner of Cameron and Lee streets where they tortured and hanged him.

5. Roberts Memorial Chapel

The McCoy family belonged to Roberts Memorial Chapel at 606 S. Washington Street. Rev. William Gaines, who was the pastor, performed the funeral service for McCoy.

As a home to one of the oldest African American congregations in Alexandria, this site is significant to Alexandria’s African American heritage.

In Memoriam: Benjamin Thomas August 8, 1899

Benjamin Thomas Narrative

Benjamin Thomas

August 8, 1899

It was 8PM on a clear Monday night the 7th of August 1899 when two policemen knocked on Elizabeth Thomas’ door. They were there to arrest her 16-year-old son Benjamin for an alleged attempted assault. [6]

Earlier that day, Lillian Kloch, a seven-year-old white girl who lived next door was sent by her parents to retrieve an ax from the Thomas family. Screaming, she ran home without it, and told her parents that Benjamin had pulled her into the house and attempted to assault her. After hearing his child’s story, Edward Kloch swore out a warrant and had the teen arrested. [6]

Thomas denied the charges and proclaimed his innocence, but the officers pulled him from the safety of his home and took him to the police station anyway. Benjamin Thomas was locked in a cell. He would never see 700 N. Patrick Street again. [4]

That same night, after hearing a group of white men threaten to lynch “some negro,” James Turley and Albert Green organized Alexandria’s African American men. Remembering the sudden lynching of Joseph McCoy and at a time when the South was experiencing a record number of manhunts and lynchings, the Black men were determined to protect Thomas from the same fate.

First, the men who were leaders in the Black community, went to the police and told them that Benjamin Thomas was in jeopardy of being lynched. They offered to help protect the youth, but the officers rejected them. Next, they went to Mayor George L. Simpson and told him of the danger Thomas faced. He told them to go home.

But these heroes had no intention of leaving and late into the night, more than 100 Black Alexandrians stood vigil around the police station. Their nonviolent presence irritated some white citizens and annoyed Lieut. James Smith to the point that he complained to Mayor Simpson who gave him permission to order them home and arrest any who didn’t comply. Smith led officers and deputized citizens out into the streets to question, antagonize and arrest Thomas’ defenders. [7]

The next day, Mayor Simpson severely punished the 15 Black men who had been arrested and charged with “disorderly conduct” and “attempting to incite a riot,” with significant fines. Most couldn’t afford the debt they incurred trying to uphold the law and were forced to labor for the city on the chain gang.

During the hearing, police officers did not bring up the fact that these men had overheard a threat to Benjamin’s life and were requesting more protection for him. Instead, they told the packed courtroom and newspapermen that while white Alexandrians slept in their beds, the Blacks were in the streets threatening them - setting the scene for a race riot, or a lynching.

That same morning, Thomas’ 7-year-old accuser Lillian testified before the court about his conduct the previous day. Without hearing from Benjamin Thomas, Mayor Simpson sided with the child and placed the teen into the custody of the City Sergeant B. B. Smith. Thomas was taken to the City Jail at Saint Asaph and Princess Streets until a grand jury could meet. [8]

All day long, white Alexandria revisited grievances that still festered from when they lynched McCoy - the fear of retaliation from armed African Americans, the ridicule from big city newspapers from Boston to Washington, D.C., the Governor’s investigation of the lynching. They imagined armed Black men looking for a fight and parading through the streets the night before; and complained they wouldn’t have dared had the Kloch’s been rich instead of poor. By late afternoon, it was clear, a lynching was in the works.

That night, an armed and angry crowd of between 500 and 2000 white people gathered outside the prison walls and crudely demanded authorities turn the teen over to them. Officers made a half-hearted attempt to scare them off, but when members of the mob fired their guns at the building, the police went to the jail’s office and hid. [8]

Fifty men went into the jail to bring Thomas out. But breaking into the corridor took more work than expected and several times they returned to those waiting outside to ask for help. For more than an hour they rooted around the jail with little interference from the officers on duty. [8]

Mayor Simpson took advantage of the lull, appearing with a dozen friends and officials to address the crowd, he said,

“Gentlemen and fellow citizens, he shouted, in the name of the law I beg of you to disperse. As Chief Executive of the City of Alexandria I give you my solemn promise that the Grand Jury shall be empaneled tomorrow, and that the case of this negro whom you are seeking to lynch shall be brought before it. He will be indicted, and I promise you a trial on the following day and a speedy execution. If he is not indicted tomorrow, I give you my word of honor as Mayor and as a citizen that I will personally lead you tomorrow night in lynching this negro, and I defy any man to point to an instance where George L. Simpson has ever failed to keep his word,” according to the Washington Post.

The article reported that Simpson’s statement was met with derision.

Members of the mob dismissed the mayor with a shout: “lynch the negro.” [8]

Meanwhile, those inside had gained access to the cells and in their search for Benjamin, terrorized a number of prisoners before finding the youth hiding in the basement.

“As the mob caught sight of him, a piercing shriek of exultation rent the air. Pistols were fired and a throng of hundreds charged down upon the helpless victim,” wrote The Washington Post, August 9, 1899.

Outside, they threw him into the waiting crowd.

Officer Wilkinson drew his pistols and told the lynchers to stand back –he told them they had the wrong man. As the mob retreated, he took the noose from Benjamin’s neck. In the next moments, Thomas almost escaped, making it three quarters of a block before the spell wore off and he was pulled back into the vicious throng. [8]

They placed a rope around his neck, in his mouth and under his arms and ran down Saint Asaph Street dragging him over cobblestones. For over a half of a mile, they struck, pierced, bludgeoned, kicked, and wounded Benjamin who cried out for his mother as he struggled to free himself.

At the corner of King and Fairfax Streets, the white citizens of Alexandria hanged Benjamin Thomas from a lamp post. The boy’s neck did not break, and he struggled to live for more than 20 minutes. [9]

Officer Wilkinson cut the suffering boy down and laid him on the ground. He tried to use his revolver to keep the lynchers away, but all at once they were there kicking and beating the boy until someone put a gun to Benjamin’s heart and fired. [9]

In the wake of the devastating murder, the African American community in Alexandria and Washington, D.C. rallied. Servants in both cities refused to go to work for their white employers, several Black men attended the inquiry into his death as human rights witnesses, a fundraiser for the family was held, secret meetings were had to consider moving his body from a pauper’s grave to Douglass Cemetery. [10]

Alexandria’s African American leaders planned a mass meeting for Thomas’ memorial service at Shiloh Baptist Church. More than 600 people attended and protested the terror, proclaimed Thomas’ innocence, and called for an economic boycott. [11]

This narrative for Benjamin Thomas was written by Tiffany Pache, ACRP Coordinator, and is based upon newspaper accounts and the research report produced by ACRP’s volunteer research committee that can be read on the ACRP web page.

Eulogy for Benjamin Thomas

Remarks by Rev. Dr. Taft Quincey Heatley of Shiloh Baptist Church, the church that held Benjamin Thomas funeral service in 1899.

Benjamin Thomas Eulogy

August 8, 2021

The word eulogy has its etymological roots from the Greek word eulogia it means to give words of praise and words of blessing. Its counterpart in the Hebrew is Baruch, that of praise and blessing both of divine and human intention.

It’s easy to give words of praise when you know the span of a life of someone whose life was well lived, you know their accomplishments, you know what they meant to society, they lived a long life and in the timeline of the dash between their beginning date and end date there is a multiplicity of things to which you can give praise.

But I must be honest, as we stand on this place 122 years ago, I have a hard time seeing words of praise anywhere, how is it that we can give praise to a teenager who had no idea what he was entering in simply because he was at his home?

How is it that we can give words of praise when this type of act was known as common place in a country that - at that time - in the 19th century - was supposed to be a Christian nation?

I think about how can we give words of praise for this type of evil and heinous act, what crime did Ben commit? He was charged on trump charges, his only accusation was something he had nothing to do with, he could not help the ewe of which he was given by God. And yet it is this very same ewe that was dehumanized and looked at as if he didn’t matter.

The question I have is that of that angry mob of 2000 - how many of them ever stepped foot into a church or synagogue or some temple of worship? How many of them proclaim Christ as their savior? Because if I could go back in time, I would take my seminary degree and put it into a JD and ask some questions.

Did you not know that this was your brother in Christ?

Did you not know that at 14 he was baptized in the water, and he came up a new being?

Did you not know he received the right hand of fellowship?

Did you not know he was your neighbor?

And it’s the irony that his neighbor was the one who convicted him simply for saying hello.

I got questions that I would ask these gentlemen. Maybe all of them were not professing and Bible toting Christians, but then I would ask them - what in their humanity would feel that you would have the authority and the power to act as if you were God to decide when someone leaves this place?

I got questions.

Where’s the praise? Did they not flip and look at Deuteronomy 6, 4, and 5 and see the Shema that they have to love the lord god with all their heart, all their soul with all their mind?

Did they not hear the words of the gospel: Mathew 22:37 and 42; when Jesus said the very same words?

I know we are at a government whatever you want to call it, but this is my member, my Christian brother in Christ so I have to speak from my faith tradition with respect for all other faith traditions.

Did they not hear the words that Jesus says when the pharisees question him and ask him, ‘what is the greatest law?’ and Jesus repeated the Shema, Deuteronomy: 6, 4 and 5 and then said this from Leviticus:19 that, ‘you are to love your neighbor as yourself’ for on these two commandments hang all the law of the prophets.

Was Ben your neighbor?

Did his life matter?

Apparently not, and as we stand here 122 years later trying to give words of praise, I struggle to find them. But I recognize that hope is still available. Do you know because Ben gave his life to his Savior, in our faith tradition, we have this belief that to be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord. And the truth is, Ben shared some esteemed company and high company of One who was accosted by a mob.

As I flip over the Holy Writ and look for inspiration, I see there was another man who was approached with swords and spears and an angry mob. There was another man, I don’t know if August 8th in 1899 was a Thursday, but I do know of another man, on a Thursday who was accosted by a mob.

He too was accused of something he did not commit.

He too had his time in court, but all the accusations outweighed his testimony because he was instructed not to say a word.

He too had to march on some cobble stone streets after being beaten, after being pelted, after being whipped, after being mutilated.

He too had to walk this place that we call the Via Della Rosa. Now in no more form or fashion am I saying that this teenage boy Benjamin Thomas is in the same category of the One that I calm to be Savior, but I am saying this: there is this strange correlation between the lynching tree and the cross, according to James Cone.

That innocent people are not put on display, I believe, that even posthumously Ben your name still has power - even 122 years later, we recognize what was done to you, we recognize that your name should be spoken - whether its Thomas or Thompson - we know who you are.

My only hope is to believe that as my faith teaches me that when this child was taken to prison; when this child was accosted from the jail; when this child was dragged through the streets; when this child had a rope around his neck; when this child who actually died from a bullet wound to a heart before they ever put him on a lamp post; when this child - in his moment -that my god sent a heavenly host of angels to sing the words of that negro spiritual, “Yes, I want Jesus to walk with me, I believe there were Holy Angels walking with him through the entire time. Yes, the mob saw the body, but he was already gone. His spirit lives this day. And Ben, if I get there with you, I just want to see what your glorified body looks like. I want to see what it looks like when the man in whom you believe wiped away every tear and dried every eye. I want to see what your glorified body looks like and those of us who remain, even as we commemorate this heinous and evil fabric of American history, we recognize that we too can still be inspired and look at one another as neighbors and learn to speak and say ‘Hello.’

God bless you.

Poem: In Memory of Benjamin Thomas, 1883-1899 (2022)

In Memory of Benjamin Thomas, 1883-1899

© Zeina Azzam, Poet Laureate of the City of Alexandria, Virginia, August 2022

A sense of foreboding spread

through Alexandria’s streets

the night before the lynching.

The crescent moon, as it set

in the western sky, illumined

scores of Black men who gathered

to protect Benjamin Thomas

as he languished in his jail cell.

But the mayor and police halted

the community’s heroic efforts

like a raging fire can silence a town.

Alone and vulnerable,

Thomas would later emit a scream

from the depth of his being,

the primal cry to his mother

for succor in his final moments.

Let us honor this voice

and this bright life

beyond his gruesome death,

this once vibrant body full of promise

now tortured and maimed

and hanged until lifeless.

With his lynching a piece of us was killed, too:

We wear the same shroud.

How do we make sense of

Benjamin Thomas’s short life?

If we callously allow simple hemp fibers

to become a noose,

a poplar tree or a lamppost

to become a gallows,

what will we fashion

of our history books?

His life breath, usurped violently,

is like ours, fragile

and full of human spirit,

innocent and vital.

One with our mother breath.

May our grief over his cruel loss

impel us to action.

May his memory nourish our resolve.

Poem: A Tale of Two Names: For Benjamin (2020)

A Tale of Two Names: For Benjamin

© An Original Poem by KaNikki Jakarta, the First Black Poet Laureate of Alexandria, Virginia

You were Benjamin Thomas

also known as Benjamin Thompson

lynched in Alexandria, Virginia on August 8, 1899

due to a varied crime

during a time

when the newspapers didn’t care enough to print your name right

That night,

the story seems a bit blurry

between blurred lines of testimony of what really took place

Your history is traced

121 years

and still unclear

Did Lillian walk by your house or come to your door to borrow an ax?

Did she flee in an outcry after an attack?

Was she with her younger brother or was she alone?

Did Lillian indeed come to your home?

I’ve read enough black history of lynching’s and tragedies

to know that even with a testimony and blatant discrepancies…

justice would not be the outcome

Accuser’s accusations could have a black person hung

Who cares if these stories where accurate? Who cares about the truth?

when the mission of the accuser is to kill the black youth

they painted you as a horrible person,

shot you in the heart and hung you from a lamp post in an attempt to burn out your light

but there were protesters of Black people willing to fight for your life

the writers stated that when they learned of this accusation, the White community was enraged

no writings about your mind state or anything that you said while you were encage

Breaking into the jail and taking your life was a white mob’s intent

while falsehoods spread that the Black community was willing to kill White residents

There was one man named Albert Green

who was jailed when he tried to intervene

The journalist wrote that they didn’t think you would be lynched

especially since Lillian and her parents were the only witnesses

how frightening it must have been listening and wondering why

and having to sit silently with no chance to testify

I’m not sure if you were 16 or 20 in your final days

because the writers also didn’t care to verify your age

to them you were just another black boy

killed two years after they murdered Joseph McCoy

I’m certain that living in this city; Joseph’s murder was a tragedy of which you knew

and never in yourself imagination you would think this would also happen to you

Throughout the city, the Black community demanded your protection

and was willing to help in your defense

And here we are 12 decades later to hold up your name in remembrance

You didn’t deserve to die this way; leaving your mother heart broken and in grief

Unfortunately your story doesn’t leave us in utter disbelief

You deserved to be the person to create your own legacy

Yet, you are another fallen ancestor in our tragic history

We will pour libations and hold you in the light

and say your names as Thomas and Thompson in an attend to get it right

We will make people aware of injustice that was done to you

and say you lived until you were murdered and leave that to be true

These sad murder stories are a part of the city of Alexandria’s DNA

and affect what Alexandria was and continue to affect Alexandria today

We celebrate your life and create a memorial for you, Benjamin

and mourn at the loss of who you could have been

Poem: Take Him Out (1899)

Printed in the Colored American (Washington, D.C.), August 26, 1899, page 4. Reverend Lott was an early organizer of the Afro-American League in the District of Columbia and lived at 818 North Columbus Street. Alexandria City Directory, 1899.

“TAKE HIM OUT!”

By Reverend A. A. Lott

(Inspired by the Alexandria,, Va., Lynching)

What means this howling, hideous shout

“Take him out! Take him out!”

What can be all this noise about,

“Take him out! Take him out!”

The midnight shriek reached the sky,

All over town both far and nigh,

The sound shocks every passer by,

“Take him out! Take him out!”

Is this for crime that some one did,

That fiends should keep the secret bid,

And enter doors the laws forbid,

Crying-

“Take him out! Take him out!”

What means this running through the street,

As though upon a swift retreat,

And crying as they stamp their feet,

“Take him out! Take him out!”

Look! How they rush with furious glare,

While at the jail they wildly stare;

Shooting their pistols in the air,

Shouting-

“Take him out! Take him out!”

See! They have him in their grasp,

The rope around his neck is fast,

They drag him through the street at last,

Crying-

“Take him out! Take him out!”

The victim pleads but all in vain,

Their fury he could not restrain,

With murder stamped upon their brain,

Crying-

“Take him out! Take him out!”

Upon a lamp post now hard by,

The furious mob did swing him high,

And left him all alone to die,

Without Crying-

“Take him out! Take him out!

The blood that stained the rugged street,

Where horses tread with noisy feet,

Still cries to heaven for Justice sweet,

Upon the cryers-

“Take him out! Take him out!”

O! Land of Liberty and might,

Can Justice look on such a sight,

As on that memorable night,

When they-

Took him out! Took him out!

Eternal King! Almighty God,

Send not Thy judgment hence abroad.

Keep back Thy terrible, chastening Rod,

From those who-

Took him out! Took him out!

A majority of the soil collected for Benjamin Thomas was excavated from 720 N. Patrick Street. In 1899, the Thomas family lived on this block in the predominately African American neighborhood known as Uptown.

Soil was also collected from Thomas’ home where he lived and was arrested at 700 N. Patrick Street, then from Hard Corner where Princess and N. Fairfax meet, the jail on St. Asaph where he was kidnapped by a lynch mob, and from the site of his lynching at Fairfax and King Streets. This was mixed with soil from the Odd Fellows Hall where protest meetings occurred after his death, his home church, and locations significant to the heritage of the African American community in Alexandria.

The combined soil representing the life and death of Benjamin Thomas has been placed in a vessel engraved with his name made by students from Jefferson-Houston IB K-8 School led by their technical education instructor Nicole Reidinger.

6. 700 N. Patrick Street

On August 7, 1899, Benjamin Thomas, 16, was at his home at 700 N. Patrick Street when Lillian Kloch, 7, a white girl who lived at 702 N. Patrick Street, came by to retrieve an ax.

Hours later, two police officers knocked on the Thomas’ front door. They held a warrant for Benjamin’s arrest sworn out by the girl’s father, Edward Kloch. He was accused of criminally assaulting the girl and despite his plea of innocence the officers arrested him. That night, as he was pulled out of his mother’s arms, Benjamin saw his house for the very last time.

7. Hard Corner

On the night that Benjamin Thomas was arrested, more than 100 African American men gathered on the street corners around the police station after overhearing a group of white men threaten to lynch the youth. Their offers to help law enforcement protect Thomas were rejected by police and Mayor George Simpson. Refusing to recognize their valid concerns, police arrested the ring leaders at the intersection of Fairfax and Princess Streets – a crossroad at the heart of The Berg known at the time as Hard Corner. Soil from this spot was excavated to represent these local

8. City Jail

On Tuesday, August 8, 1899, Mayor Simpson placed Thomas in the custody of the City Sergeant. Thomas was moved to the City Jail at 401 N. Saint Asaph Street to wait for a grand jury to meet. According to newspaper sources, a lynch mob surrounded the jail at 11 p.m., sought out Thomas, and tortured him as they paraded him through town.

9. Lynching Site

On a lamppost at the intersection of S. Fairfax Street meets King Street a lynch mob hanged Benjamin Thomas.

10. Odd Fellows Hall

The late 19th century brick building at 411 S. Columbus Street was an important gathering place for African Americans at the turn of the last century. In the wake of the Thomas lynching, the African American community rallied and held a series of protests - some of which were planned in this building.

11. Shiloh Baptist Church

The Thomas family belonged to Shiloh Baptist Church at 1401 Duke Street. Two years before his lynching, Benjamin was Baptized and became a member of the church. More than 600 African Americans from Alexandria and Washington, D.C. attended his memorial service at Shiloh. The church was established in 1863.

Alexandria’s Historic African American Neighborhoods

In remembrance of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas, soil was collected from several historic African American neighborhoods in Alexandria.

12. The Bottoms

Established in 1790, The Bottoms was the first African American neighborhood in Alexandria. It was settled by Free Blacks who were allowed to hold long term rental agreements with property owners. It is called the Bottoms because surrounding streets are at a higher elevation. Joseph McCoy’s home and Odd Fellows Hall are in The Bottoms community.

13. Hayti

A second African American neighborhood was developed in the early 1800s with the help of Quakers Mordecai Miller and his son Robert. Mordecai emancipated several slaves and testified to the free status of many of Alexandria’s free Blacks who often had to prove their status to avoid being enslaved. Mordecai built nine houses on the 400 block of S. Royal Street and rented them to free Blacks. When Robert became president of First National Bank of Alexandria, he then sold the homes to their Black renters. The neighborhood grew to include the 300 block of S. Fairfax Street. It is thought that residents named the area Hayti in recognition of the Haitian Revolution in the 1790s.

14. The Berg

During the Civil War, African Americans escaping slavery arrived in Union occupied Alexandria in large numbers. The bulk of these refugees established a neighborhood north of King Street called The Berg, named after Petersburg, Va. from where many had escaped. In the 1870s, the neighborhood was a hot bed of radical republicanism. African Americans from this community held leadership posts in the local and state republican party. On the night of Benjamin Thomas’ arrest, many of the men from this neighborhood were involved in trying to protect the youth from a threatened lynching.

15. Fishtown

Just to the East of The Berg was Fishtown, a seasonal village of enslaved and free African Americans that originated in the 1700s along the waterfront. Each fishing season (March to May), small wooden shacks and stalls would spring up at the foot of Oronoco Street where up to 600 Black’s counted, beheaded, gutted, cleaned, and salted thousands of fish for sale. By the mid-1800s, Fishtown included land from Princess to Oronoco and from Union Street to the Potomac River.

By 1920, Fishtown was gone. Today, Founder’s Park stands in its place. Soil from this location was collected in recognition of the Black men and women who lived and labored in the fisheries.

16. Uptown

The streets that make up the neighborhood were laid out as early as 1796, but the area was mainly developed after the Civil War. By 1899, rowhouses were packed tightly together merging The Hump and Colored Rosemont into Uptown. The majority of residents were Black, however, white people also lived in this district.

As the talons of Jim Crow gripped Alexandria during the 20th century, the 1100 Block of Queen Street became a hub for Black-owned businesses.

The Thomas family lived in Uptown.

African American Heritage Sites

Soil was gathered from sites of significance that recognized Alexandria’s African Americans role in the struggle for equal rights and combined with soil representing the lives of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas.

17. Alexandria Library on Queen Street

Two decades before the Civil Rights movement spread through the south, Black attorney and activist Samuel Tucker led a sit-in at the Alexandria Public Library. In 1937, the Alexandria Free Library opened, but African Americans were not allowed to use it. After failing to convince officials to provide library services to both white and Black Alexandrians, Tucker organized a protest.

On August 21, 1939, five African Americans, Otto Tucker, Edward Gaddis, Morris Murray, William Evans and Clarence Strange, went into the reading room, pulled books from the shelves and when asked, they refused to leave. They were respectful, well dressed, and nonviolent, just as Tucker had instructed them to behave. The five men were arrested and charged, but then they were released without a judge’s ruling. Tucker had been counting on representing the men in court, but when the charges were dropped his plan was thwarted.

As a result of the protest, the city built the small Roberts H. Robinson Library for African Americans which opened in 1940. Tucker and other Blacks felt this was an inferior option and continued to advocate for library privileges at the Queen Street building.

18. Alexandria Black History Museum

As a result of the 1939 sit-in, the Roberts H. Robinson Library was constructed at 902 Wythe Street and opened in 1940. Once a segregated reading room, the building is now the Alexandria Black History Museum. The museum collects and interprets Black Alexandrian’s contributions to local and national history and culture.

19. The Departmental Progressive Club

In 1927, seven African American’s who worked for the federal government, established the Departmental Progressive Club to provide a setting for Alexandria’s Black community to meet and hold social events before, during, and after segregation. Known as the Secret Seven, these men worked to integrate Alexandria City Public Schools and fought tirelessly for social and civil rights in this city. Members continue this legacy today.

20. Parker-Gray High School

Due to segregation in education, the Parker-Gray High School opened in 1920 to teach black students in grades 1 thru 8 at 901 Wythe Street. The name comes from the former principals of boys’ and girls’ schools set up by the Freedman’s Bureau after the Civil War.

At its opening, the Parker-Gray School employed nine teachers and was led by Principal Henry White. Because the City was meager in its support, members of the community banded together to provide the furniture, equipment and supplies needed to teach the children.

In the 1930s high school grades were added and in 1936, the first students graduated. In 1950, a new Parker-Gray High School was built on Madison Street and the school on Wythe again became an elementary school. It was named after Charles Houston, the NAACP lawyer and civil rights leader.

Parker Gray produced doctors, lawyers, judges, a brigadier general, the first African American NBA player, numerous college and high school coaches and Federal workers, scientists, musicians, and businessmen of note. Today, the site of the old school is the Charles Houston Recreation Center that houses the Alexandria African American Hall of Fame to recognize the many impressive graduates.

21. Alexandria African American Heritage Park

Established on the site of the oldest known independent African American burial ground, the Black Baptist Cemetery, the park with its bronzed memorial, Truths that Rise from the Roots – Remembered by Jerome Meadows, honors the contributions of African Americans to the growth and success of Alexandria.

The cemetery was chartered in 1885 by the Silver Leaf Colored Society of Alexandria.

Statements from Elected Officials

Senator Mark Warner

Senator Mark Warner

United States Senate

September 24, 2022

Dear Friends,

I am writing to join the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project in memorializing Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas, who were lynching victims in the late 1800s, during today's Soil Collection Ceremony.

It is important that we take time to reflect upon the lives of Mr. McCoy, Mr. Thomas, and the many Black Americans who were heinously lynched in Alexandria and in communities across the United States during some of our darkest days. According to data from the Equal Justice Initiative, lynching was used in the United States as an instrument of terror and intimidation more than 4,000 times during the 19th and 20th centuries. Reckoning with this history is an essential step in identifying and addressing its modern-day manifestations, especially in our housing, education, voting, and criminal justice systems.

The Emmett Till Antilynching Act that was signed into law by President Biden on March 29, 2022, is long overdue legislation that finally begins to acknowledge a painful chapter in our history by designating lynching as a federal hate crime. Over the past century, Congress failed to pass anti-lynching legislation nearly 200 times. Following these failures, I was proud to join my Senate colleagues in unanimously passing this important measure, which is a critical step forward in renewing our resolve to build a strong, inclusive future together.

I send my best wishes for a meaningful event and a successful trip to Montgomery, Alabama in October to bring this soil to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Sincerely,

MARK R. WARNER

United States Senator

Senator Tim Kaine

Senator Tim Kaine

United States Senate

September 24, 2022

Dear Friends,

I am grateful to the City of Alexandria and the community at large for your ongoing efforts to remember victims of lynching in Alexandria, Virginia. By confronting the failures of our past, we take steps in creating a more equitable future for the Commonwealth and our nation. Your commitment to telling the full and truthful story of Alexandria's history, is a step towards healing for our nation.

By memorializing Joseph McCoy, Benjamin Thomas, and other victims of lynching, we acknowledge the dark history of violence against African-Americans in our country. Racial injustice is part of not only our history but also our present. That is why, in March of this year, President Biden signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act into law. This legislation makes lynching a federal hate crime; improves

transparency in policing; improves police training and practices, and holds police accountable in our courts.

The stained legacy of this egregious period in American history must never repeat itself, and the Alexandria Remembrance project is an important effort to dismantle the architecture of discrimination in our nation.

Sincerely,

Tim Kaine

Congressman Don Beyer

Congressman Don Beyer

United States Congress

This statement was submitted for the Congressional Record

September 2, 2022

Remarks by the Honorable Donald S. Beyer Jr.

HONORING THE MEMORY OF JOSEPH MCCOY AND BENJAMIN THOMAS

Madam Speaker, I rise in memory of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas – and to commend the City of Alexandria for its work on the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project (ACRP).

Through its partnership with the Equal Justice Initiative, the ACRP has brought our community together to remember the city’s history of racial terror and to memorialize Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas, who were lynched in 1897 and 1899, respectively. These lynchings were two of 86 documented lynchings committed in Virginia between 1880 and 1930. These acts of premeditated violence were deliberate attempts by whites to terrorize and control black populations across the state.

As our community convenes again on September 24, 2022 we do so to collect soil representing these two young men’s lives. In October, Alexandrians will then make a pilgrimage to Montgomery, Alabama to deliver this sacred soil to its final resting place at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

These events also occur during a year in which the Emmitt Till Antilynching Act, a federal bill making lynching a federal hate crime, was signed into law by President Biden on March 29. I was proud to support this long overdue legislation in the U.S. House of Representatives, but also recognize that we still have much more work to do.

It is incumbent on all of us to remember this shameful episode of our history and others like it. In doing so, we are better able to see the continuous chain of racially motivated violence against Black Americans that spans our nation’s history. We can truly honor the memories of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas, along with the countless number of named and unnamed victims of racial violence, by seeking justice for all Americans and working to build a more inclusive society.

Donald S. Beyer Jr.

Eighth District, Virginia

Governor Glenn Youngkin

Governor Glenn Youngkin

Governor of Virginia

September 24, 2022

Dear Friends,

On behalf of the Commonwealth of Virginia, I wish to add my appreciation to the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project (ACRP) for its efforts in the remembrance of Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas, lynching victims in 1897 and 1899.

I congratulate ACRP on its work to bring attention to "the good and the bad" pieces of our history in Virginia and assist in more accurately depicting and calibrating past events in the Commonwealth.

The First Lady and I stand with the City Alexandria as it recognizes the terrible actions taken by its citizens in these lynchings approximately 125 years ago. We must never shy away from the tapestry of events throughout the history of the Commonwealth in order to strengthen the Spirit of all Virginians.

Sincerely,

Glenn Youngkin

Lieutenant Governor Winsome Earle-Sears

Winsome Earle-Sears

Lieutenant Governor of Virginia

Letter from Lieutenant Governor Winsome Earle-Sears

September 24, 2022

Dear Alexandria Community Remembrance Project,

Today, you gather in remembrance of a dark time in our American History: racism and hate covered our land. Rightfully, we honor the memories of those who bravely fought to secure for us a better tomorrow.

We reflect on the life of Joseph McCoy- a Black nineteen-year-old who was lynched in 1897 based on the word of a white man. A mob broke into the jail, dragged him out, and tortured him. The actions of the mob were so repugnant, that the newspapers, at the time, refused to publish the most graphic details. Despite this brutality, justice was never delivered for the McCoy family.

Two years later, in 1899, the mob was back. This time their homicidal intent was fixated on a Black sixteen-year-old boy named Benjamin Thomas- whose alleged crime was reported by an eight-year-old! The city officials ignored the pleas from the African-American community who knew what lay ahead. The mob dragged him from his cell, throwing bricks, iron, and stones; however, that did not quell their appetite. The mob did not cease until they had stabbed, shot, and hung Thomas!

These two lynchings represent a time when the law treated our Black community differently than our white neighbors. But today, as we remember the young souls-that were lost in this fight, we can proclaim that they did not die in vain. Since those somber days, our Commonwealth and nation has changed. There is no better proof of that than myself. I write to you as a Black woman, who is second in command in the former capital of the Confederacy. Our nation may not be what she should be, but thank God she isn’t what she once was.

To God be the glory,

Winsome Earle-Sears

Lieutenant Governor

Commonwealth of Virginia

Jason S. Miyares, Attorney General

Jason S. Miyares

Attorney General

Letter from Attorney General Miyares

September 24, 2022

Dear Friends,

Virginia has played such a pivotal role in the birth and foundation of our nation’s story. While so much has been accomplished in our Commonwealth, the evil of slavery and lynching is a tragic part of our history that we must never forget.

As the Office of Historic Alexandria hosts a Soil Collection Ceremony in remembrance of lynching victims Joseph McCoy and Benjamin Thomas, we must reflect upon their lives, mourn our nation’s past sins, and recognize our nation’s progress towards racial equality. I applaud the City of Alexandria and the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project for urging us to remember the past, and also challenge us to look to the future to honor the individual dignity of every person.

It is an honor to serve as your Attorney General. Our office is committed to seeking equal opportunity and justice for all Virginians.

Sincerely,

Jason S. Miyares, Attorney General

Remembrance Walking Tour

This walking tour through historic Old Town Alexandria allows you to explore a few of the sites associated with a disturbing part of Alexandria’s past. Thirty years after the Civil War, white conservative democrats were in control of Alexandria’s government, economy, police, and its major newspaper. The lynching of Joseph McCoy in 1897 and Benjamin Thomas in 1899 and the aftermath terrorized the African American community in this city. This short self-guided walking tour will take about 45 minutes to an hour. This is a difficult history to reflect upon and we recommend preparing mentally prior to starting.

Social Justice Reading List for 2022

About the Reading List

Here are is a Social Justice Reading List, provided by the City of Alexandria Library staff. We hope you will find these additional selections educational, and moving. These titles - both fiction and nonfiction - provide context for discussion of race, class, violence and American society.

See also:

Readings for Adults

Biography

- Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the struggle for equality – Omiko Brown-Nagin

Non-Fiction

- Between the World and Me – Ta'Nehesi Coates

- Blackballed: The Black Vote and US Democracy – Darryl Pinckney

- Don't Call Us Dead – Danez Smith

- Driving While Black: African American travel and the road to civil rights – Gretchen Sullivan Sorin

- "Ebony & Ivory: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America's Universities" – Craig Wilder

- Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower – Brittney Cooper

- Fear of black consciousness – Lewis R Gordon

- For White Folks Who Teach in the 'Hood... and the Rest of Y'all Too – Christopher Emdin

- Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women that a Movement Forgot – Mikki Kendall