History of Alexandria’s African American Community

Resources for the study of the African American Community

Alexandria's African American Community: Online Resources include books and CDs, brochures, lesson plans, Oral History transcriptions and archaeological site reports.

African Americans in Alexandria, Virginia: Beacons of Light in the Twentieth Century

This book, by Audrey Davis and Char McCargo Bah, is available for sale at the Museum, at the Historic Alexandria Museum Shop located at The Lyceum, and online from The Alexandria Shop. All proceeds will go to the Museum to assist in their programming.

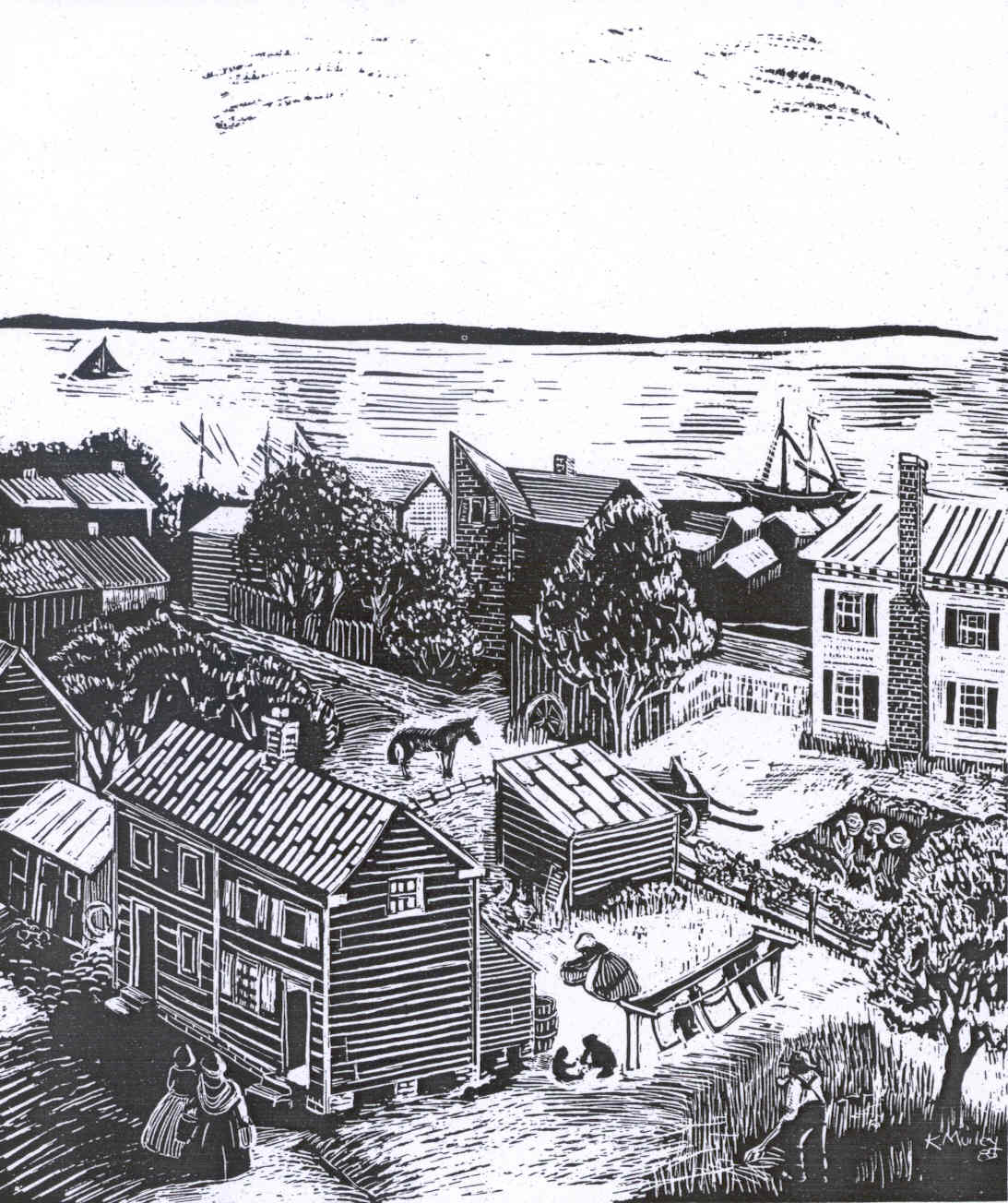

Early Free Black Neighborhoods

In 1790, when the first federal census was taken, 52 free Blacks were recorded as living in Alexandria. The first community of free Blacks formed at the southwestern edge of the city and became known as “The Bottoms.” By 1810, this neighborhood had extended to the southeast and a new community, Hayti, sprang up to the east.

In mid-century, Uptown began in the northwestern section of Alexandria. A community known as Petersburg (also known as The Berg or Fishtown) developed in an area just back from the north waterfront.

The free Black population increased dramatically during the period in which Alexandria was part of the Federal city, rising to 836 by 1820 and continuing to expand until 1846 when Alexandria retroceded from the District of Columbia and once again became part of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

- Hayti: One of Alexandria's African American Neighborhoods, Out of the Attic, Alexandria Times, April 29, 2021

- Uptown: From 1796 Platt to National Historic District, Out of the Attic, Alexandria Times, May 20, 2021

- From Grantville to Petersburg to The Berg, Out of the Attic, Alexandria Times, May 27, 2021

The 46 Petitioners: Social Justice in the Age of Nat Turner

The 46 Petitioners: Social Justice in the Age of Nat Turner

Mapping Alexandria's Free Black Citizens

Dr. Garrett Fesler introduces his research on the 46 free Black residents who published a petition in the local newspaper asserting their loyalty to the “authorities of the town” in the aftermath of the Nat Turner uprising in 1831.

Slavery in Alexandria

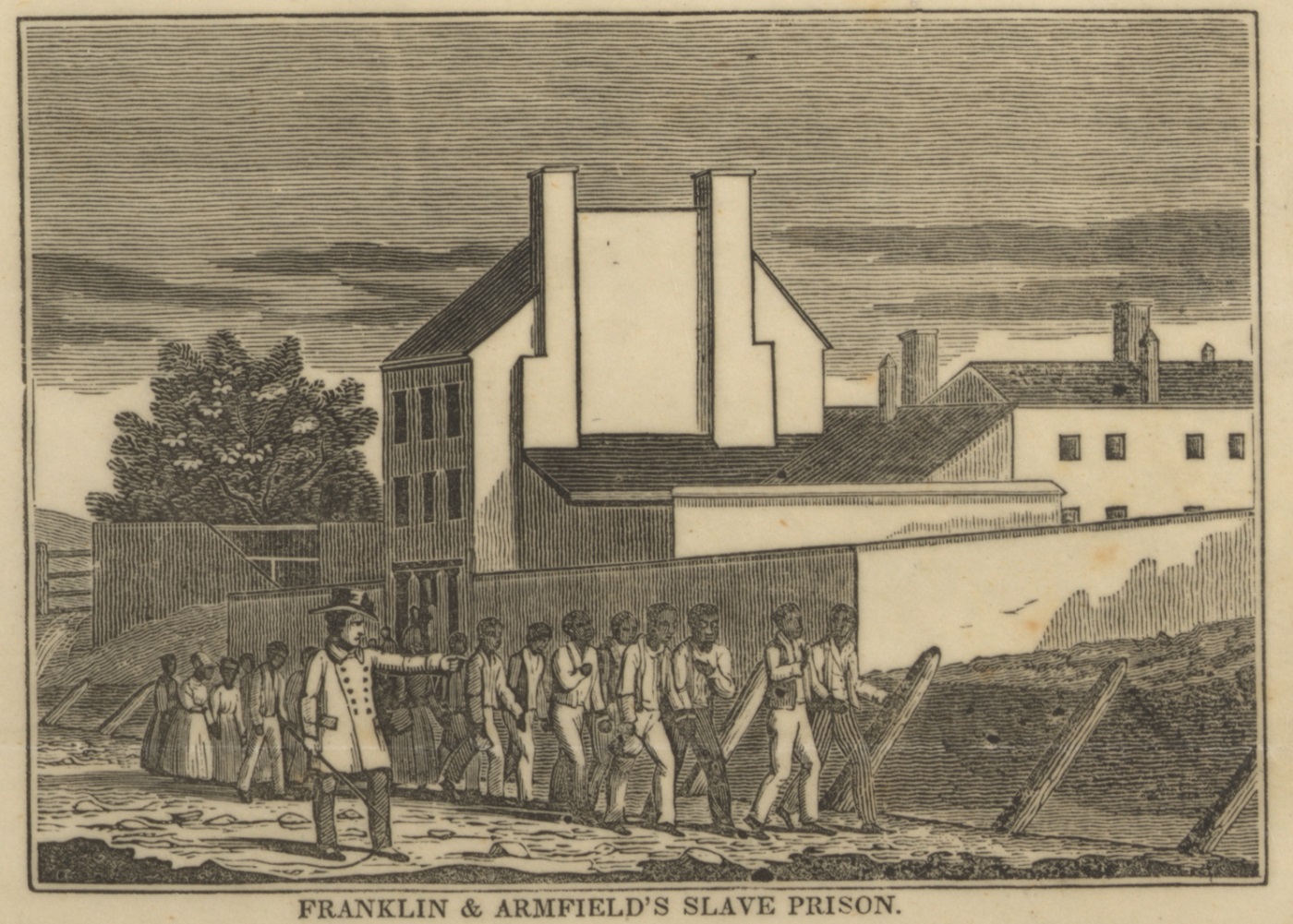

Prior to the Civil War, Alexandria was also home to one of the largest slave-trading operations in the country.

The building at 1315 Duke Street, now the Freedom House Museum, was once part of the headquarters for Franklin and Armfield, the largest domestic slave trading firm in the United States. Enslaved people were brought from the Chesapeake Bay area and forced to the slave markets in Natchez, Mississippi and New Orleans either by foot, in coffles, or by ship. Franklin and Armfield were active from 1828 until 1836, exporting over 3,750 enslaved people to cotton and sugar plantations in the Deep South. Later, other slave-trading firms continued here. A sign seen in Civil War period photographs has the name of Price, Birch & Co. During the Civil War the building and its surrounding site were used as a military prison for deserters, the L'Ouverture Hospital for black soldiers and barracks for contrabands who fled the confederate states and sought refuge with Union troops. Freedom House Museum was purchased by the City of Alexandria in 2020.

The Bruin Slave Jail at 1707 Duke Street was purchased by slave trader Joseph Bruin in 1844 as his holding facility, or "slave jail" for enslaved people awaiting sale to individuals and other traffickers. In December 1845, he and partner Henry Hill advertised in the Alexandria Gazette: "NEGROES WANTED: All persons having Negroes to sell will find ready sale and liberal prices for them by calling at the new establishment of BRUIN & HILL."

Harriet Beecher Stowe, in The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1854), described how she employed her knowledge of Bruin's slave jail as background for her explosive 1852 novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin. In The Key, she described the escape of a number of enslaved people from Washington, DC, on April 15, 1848, in the ship Pearl. They were later captured and returned for eventual sale in New Orleans. Bruin & Hill purchased an enslaved family known as the Edmondsons and brought them to the slave jail. According to Stowe, Bruin's daughter begged that Mary and Emily Edmondson be excluded from the group that was eventually sent to New Orleans for sale there, a group that included other Edmondson siblings. Their father, Paul Edmondson, traveled north to try and raise funds for the purchase of two of his daughters. He eventually met Reverend Lyman Beecher, Stowe's father, who raised the sum overnight. Bruin and his "large slave warehouse" are mentioned approximately 20 times in The Key. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Bruin fled Alexandria but was captured and then confined in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, DC, until the end of the war. In his absence, his slave jail was used as the Fairfax County courthouse until July of 1865.

The Bruin Slave Jail is featured on the National Park Service website, Underground Railroad: Journey to Freedom. The building is not open to the public. A statue was erected at this site in 2010 as a memorial to the Edmondson sisters and others who passed through the Slave Jail. For more information, read the archaeological site report.

The Ledger and the Chain (lecture)

Joshua Rothman, author of The Ledger and the Chain talked about his book which recounts the shocking story of the domestic slave trade by tracing the lives and careers of Isaac Franklin, John Armfield, and Rice Ballard, who built the largest and most powerful slave-trading operation in American history. Their main office was 1315 Duke Street, now the Freedom House Museum, which is owned and operated by the City of Alexandria. Historian Joshua D. Rothman is a professor and Chair of the History Department at the University of Alabama.

The Civil War

![[Railroad construction workers]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2022-07/tunnel.png?itok=21nT6DQf)

During the Civil War, Alexandria was occupied by Union troops. Those escaping from slavery found safe haven in Alexandria because of the Union occupation. Alexandria's Black population reached 5,300 by 1870, and the large numbers arriving during the war created a refugee crisis. While many found employment, other Contrabands, as the freedmen were officially known, were destitute after self-emancipating, and arrived hungry and in ill health. Many were housed in barracks, and disease was rampant. In 1864, after hundreds had perished, the Superintendent of Contrabands ordered that a property on the southern edge of town, across from the Catholic cemetery, be

confiscated for use as a cemetery. Alexandria Contrabands & Freedmen Cemetery served as the burial place for about 1,800 of those who fled to Alexandria to escape from bondage. A Memorial opened on the site of the cemetery in 2014, to honor the memory of the Freedmen, the hardships they faced, and their contributions to the City.

Black regiments, commanded by white officers and designated U.S. Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.), were quickly raised by the War Department following the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in early 1863. Approximately 180,000 African American soldiers took up the call to fight for the Union, comprising more than 10% of all Federal forces. Knowing that a Northern loss could mean possible re-enslavement, freemen and those formerly enslaved showed dedication to their country and a commitment to the freedom of their people forever.

Black soldiers were buried at Contrabands & Freedmen Cemetery until convalescent soldiers at L’Ouverture Hospital protested. In response to their petition in which "We ask that our bodies may find a resting place in the ground designated for the burial of the brave defenders of our countries flag....," the soldiers gained the right to be buried in Soldiers’ Cemetery, now the Alexandria National Cemetery.

Black Soldiers in the Civil War

- The USCT and Alexandria National Cemetery (Courtesy, Alexandria Black History Museum)

- Convalescent Soldiers in L’Ouverture Hospital "Express Our Views" on Burial Location. (Courtesy, Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery)

- Fighting for Freedom: Black Union Soldiers of the Civil War. (Courtesy, Fort Ward Museum)

- Miller, Jr., Edward A. Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in Alexandria’s National Cemetery, Part I. Historic Alexandria Quarterly, Fall 1998.

- Miller, Jr., Edward A. Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in Alexandria’s National Cemetery, Part II. Historic Alexandria Quarterly, Winter 1998.

- Traum, Sarah, Joseph Balicki and Brian Corle. A Documentary Study, Archeological Evaluation and Resource Management Plan for 1323 Duke Street, Alexandria, Virginia . John Milner Associates, Inc., Alexandria, VA., 2007. Public Summary (Archaeological Site Report. In 1864, this site became part of the L'Ouverture Hospital for African American soldiers.)

History of the Contrabands & Freedmen Cemetery Memorial

This video explores the history of the founding of the Freedmen Cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1864 and the neglect and resurrection the cemetery experienced over the subsequent centuries.

Juneteenth: A Time of Reflection and Rejoicing

On June 19th, we celebrate Juneteenth (June + 19th), commemorating the end of slavery in the United States. On that day in 1865, General Gordon Granger of the Union Army and his troops arrived in Galveston to announce that the enslaved people in Texas were free and that “…rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired laborer."

In Alexandria, there has been some discussion about observing Emancipation Day on April 7th, the date that those individuals enslaved in Virginia were emancipated. With a rich history of observance beginning in 1889, Alexandrians have celebrated on different days of the year and in different months. More recently, the Alexandria Black History Museum has celebrated Juneteenth for almost 30 years.

Black Neighborhoods after the Civil War

Early Black neighborhoods expanded, and new settlements began in the post-bellum period. New settlements included The Hill (south of Hayti), Cross Canal (located on each side of the Alexandria Canal locks on the north end of town), The Hump (to the west of Cross Canal), and Colored Rosemont south of The Hump and east of the railroad. By 1910, there was almost a continuous band of African American neighborhoods surrounding the city’s center and edging Alexandria’s boundaries. The early neighborhoods of Uptown and The Berg are still viable 21st century neighborhoods. The historic African American community known as Uptown was designated as the Parker-Gray Historic District in 1984, and in 2008 was approved for listing on the Virginia Landmarks Register. It is expected to join the Old and Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.

After the Civil War, a neighborhood known as The Fort grew up around Fort Ward, one of the Union forts built as part of the Defenses of Washington. But in the 1950s and 1960s, the City displaced the residents to establish the Fort Ward Park and Museum. The City of Alexandria is working on an Interpretive Plan for Fort Ward Park to expand interpretation to include the full range of its history, especially including the African American experience and the post-Civil War Fort community. As part of this effort, archaeological investigations took place in the park between 2009 and 2014.

- The Fort: Out of the Civil War and back again, Out of the Attic, Alexandria Times, May 6, 2021

- 'Colored Rosemont', Out of the Attic, Alexandria Times, May 13, 2021

Immune Regiments in the Spanish-American War

During the Spanish-American War (1898), Black Virginians were part of “Immune” regiments that were raised throughout the South to provide troops who were allegedly immune to the tropical diseases that prevailed in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines and which proved to be much deadlier than Spanish bullets. The first of Virginia’s four Immune companies was organized in Alexandria at the Braddock House Hotel (now Carlyle House Historic Park).

- Cunningham, Roger D. We are an orderly body of men”: Virginia’s Black “Immunes” in the Spanish-American War. Historic Alexandria Quarterly, Summer 2001.

Lynchings and the Equal Justice Initiative

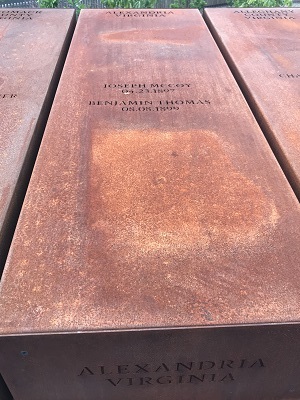

Between 1882 and 1968, 100 Virginians, including at least 11 in Northern Virginia, were lynched. The lynchings were among 4,743 reported nationwide during the same period. Lynching was never a federal offense. In Alexandria, there is documentation of the lynching of two individuals: Joseph McCoy in 1897 and Benjamin Thomas in 1899.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama includes over 800 steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. The Alexandria Community Remembrance Project is part of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), which invites counties across the country to claim their monuments and install them in the counties they represent. In addition to installing the pillars, EJI encourages participating communities to place a historical marker and to collect soil from the site of the lynchings, to "allow communities to gain perspective and experience that we believe is crucial to managing the monument retrieval process wisely and effectively." Alexandria is now undergoing this process.

Black Education in Alexandria: A Legacy of Triumph and Struggle

Black Education in Alexandria: A Legacy of Triumph and Struggle is a three part research report history of Black education in Alexandria, from 1793 to 2023.

Part 1: Early African American Education in Alexandria,1793-1870

Part 2: Separate and Not Equal, 1870-1960

Part 3: The Legacy of Segregation, 1954-2023

Also read about The History of the Parker-Gray Schools, and learn about the Parker-Gray School Archives and the 100th Anniversary.

Civil Rights: Samuel Tucker and America’s First Sit-Down Strike

An important event in 20th-century Alexandria’s African American history occurred in 1939. This event raised the consciousness of the minority community and became one of the watershed moments in Alexandria’s civil rights history.

On August 21, 1939, lawyer Samuel W. Tucker sent five young African American men to stage a peaceful protest at the whites-only library at 717 Queen Street in Alexandria, VA. The five men were arrested for disorderly conduct, but the charges against the men were dropped. In September, the court heard Tucker’s petition and agreed that African Americans should have access to a library. In 1940, the Robert H. Robinson Library was constructed for the African American citizens of Alexandria.

Learn more about the Sit-Down Strike and Samuel Tucker, a Civil Rights lawyer who staged a library sit-in at the Alexandria Library on Queen Street in 1939.

Samuel Tucker: African American Change Agents of Alexandria

The Ramsey Homes and Public Housing

Several low-income housing projects were built in Alexandria between 1941 and 1968. Most of the properties were first built as military housing. Many of them have now been replaced with scattered-site housing and mixed income communities. The Ramsey Homes, built in 1941 for African American defense workers, were demolished in 2018 to make way for a new community of low-income and market-rate units. The Board of Commissioners of the Alexandria and Redevelopment Housing Authority (ARHA) have redeveloped the Ramsey Homes at a density high enough to sustain a critical mass of low-income residents in order to maintain the strong social and support networks that are essential in low-income communities. The Lineage apartment building now sits on the site of the former Ramsey Homes. Demolition of the Ramsey Homes required Section 106 mitigation as required by Federal historic preservation laws, including historical and architectural documentation, genealogical research and oral histories, interpretive signage and community engagement.

The Alexandria Black History Museum

In 1983, through the advocacy of the Parker-Gray Alumni and the Alexandria Society for the Preservation of Black Heritage, the Robert H. Robinson Library re-opened as the Black Alexandria & Parker Gray Alumni Historic Resource Center (later Alexandria Black History Resource Center and then Alexandria Black History Museum). At first, staffing was provided on a volunteer basis by the members of these organizations. In 1987, the Alexandria City Council placed the operation of the Museum under the Office of Historic Alexandria and provided funding for an addition to the building that was completed in 1989.

Two additional properties were added to the museum in 1995. The Watson Reading Room is located next door to the Museum. The Alexandria African American Heritage Park, a nine-acre park on Holland Lane, preserves the site of a 19th-century African American cemetery.

The museum follows its mission to enrich the lives of Alexandria’s residents and visitors, to foster tolerance and understanding, and to stimulate appreciation for the diversity of the African American experience. The ABHM uses its large collection to inspire the public to explore the integral relationship between African American history and other cultural traditions. With one permanent and one rotating exhibition gallery, as well as a variety of programs and lectures, the Alexandria Black History Museum continues to expand educational opportunities for residents, scholars and tourists.

Reacting to the Death of George Floyd

Peaceful vigils, protests and other events took place in Alexandria during the first week in June, following the May 25, 2020 death of George Perry Floyd, Jr. at the hands of police in Minneapolis, Minnesota. With the murder of George Floyd, the continued push for racial equity in America reached a breaking point. Millions of people in the United States and around the world are demanding that institutions and political leaders address the disparity in treatment of African Americans. Since the dawn of American slavery in 1619, African Americans have fought for freedom, citizenship and equality in daily life. The frustration, sadness and anger of Americans is evident. Millions have chosen to protest and speak out for the right of everyone to live free of fear of police brutality, and to achieve equity in employment, health care and education. This current movement has the power to enact change for many.

The Legacy of George Floyd: the Black Lives Remembered Collection

Historic Alexandria launched a collecting initiative in 2020 and the donations received led to the creation of a new collection at the Alexandria Black History Museum.

Freedom House Museum

The Freedom House Museum honors the lives and experiences of the enslaved and free Black people who lived in and were trafficked through Alexandria.

The Freedom House Museum at 1315 Duke Street closed on March 17, 2020 due to the pandemic and on March 24, 2020, the City of Alexandria purchased the building from the Urban League of Northern Virginia. Throughout the pandemic, work continued to protect and interpret the building including the completion of the Historic Structures Report, research, and the creation of three new exhibits. The museum reopened in May, 2022, following extensive renovations.

The Freedom House Museum site is integral to the understanding of Black history in Alexandria and the United States, and is part of Alexandria’s large collection of historic sites, tours, markers and more that depict stories of the Colonial era, through the Civil War and Civil Rights eras, to today.

Taking a New Look at African American History

The City of Alexandria is expanding its study, preservation and interpretation of African American history through the following initiatives.

- Including history of The Fort neighborhood in the Fort Ward Interpretive Plan.

- Participating in the Equal Justice Initiative through the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project.

- Incorporating African American history into interpretation at all of the City-owned museums.