The City Steps In: Urban Renewal

The City Steps In: Urban Renewal

.Governments shape communities in many ways. Federal, state, and local policies and practices in the 20th century altered the physical appearance of neighborhoods and the ethnic, racial, and economic makeup of those living there.+

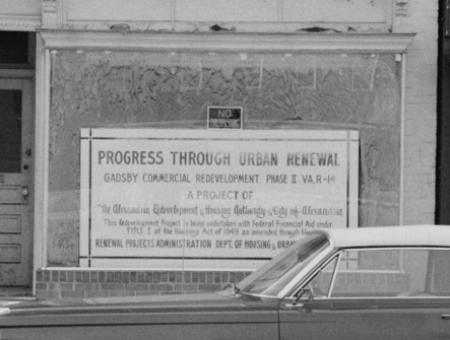

Like many cities across the country, urban renewal impacted Alexandria. In 1939, the City created the Alexandria Redevelopment and Housing Authority (ARHA), which led to the redevelopment of mixed-race neighborhoods in Old Town like The Berg and The Hump. While focused on improving the landscape and quality of life, urban renewal projects from the 1950s to the 1980s often included the displacement of residents, resulting in a more segregated city. In the 1960s, 77 structures were razed in an African American neighborhood in the Seminary area on the City’s west side to build Alexandria City High School. In the heart of Old Town, the Gadsby Commercial Urban Renewal Project changed and demolished portions of multiple blocks, including part of a racially mixed neighborhood.

Alexandria’s legacy of urban renewal has been mixed. The intent of sparking economic activity and beautification came at the cost of uprooting residents and demolishing historic buildings. The effects of urban renewal are still present today, as Alexandria continues to grow and change.

Office of Historic Alexandria.

Memories, from the Oral History Archive

Charles K. “Buster” Williams, born 1908; interviewed by Mitch Weinschenk, February 5, 1999:

I bought the house [801 Madison Street in ‘28] for $4400 with a down payment of 10%, which was 400 and some dollars…we stayed there until the Housing Authority came along and took over. That was 1944…the projects are there today. Built projects for the low income families. We fought them because they came along and set their price…I went to court for years fighting because they only offered $5000 and I owed $1700 on the property. So I fought and they eventually compromised. I asked, not knowing any better, I asked for ten thousand, and they compromised for $7500, which was half.

Sgt. Lee Thomas Young, resident of The Fort community; interviewed by Patricia Knock, November 19, 1996:

Where we’re living now…the government or something started an urban plan they call it. They buy up the wasteland – you know wherever it was rundown and they would build and – sell back to whoever…you know we had the choice – the people that were being displaced – so they wanted this for the park [Fort Ward Park] so I was displaced…They was building and as they were finishing a house, you would move in down there….I was one of the last to move in because I was living here and the people down there, they would move from one house to the other like, you know, ‘til they’d complete a house. It was rough. That would save them going into town and having to go back and all that.”

Maydell Casey Belk, resident of The Fort community 1952-1967; interviewed by Patricia Knock and others, June 6, 1994:

[The City] wanted the land for the park and my mother – she was forty and she didn’t want to sell hers. That’s when the city told her that if she didn’t sell it she would lose out because they were going to condemn the houses because they didn’t have any bathrooms, no running water and stuff...so that is when she gave in...Anybody that sold the land up at Fort Ward, they put the name on the list down here [area where former TC Williams High School and 29 homes were built] for a house...and that’s how I got it here [her home], through my mother.

Evelin Urrutia, immigrated from El Salvador in 1993; works on social justice issues for the Latin American community; interviewed by Sue Kovack Shuman, April 13, 2015:

I would like for the city try to keep this community [Arlandria-Chirilagua] the way it is…because if you see around, all over what is happening is development…When the development happens it’s a way to push people out of their community…Rent will go higher…So, what I would like is for the city to really try to maintain the community that is already here instead of displace them.

Harvey Boltwood, chair of Alexandria Chamber of Commerce in 1988; interviewed by Margie Bates, September 14, 2005:

...urban renewal...That happened in the 500 block of King Street...to put up the new courthouse...Across the street, did the same – the 500 block, 400 block, 300 block. So a lot of old businesses sort of faded away and some of them came back into the new buildings that were erected.

Vola Lawson, Alexandria City Manager 1995 - 2000; interviewed by Alice Reid, May 21, 2009:

…the Dip, which was the urban renewal area, and the northern part of Del Ray, Lynhaven, Arlandria, and Mount Jefferson. Lynhaven and Arlandria had terrible problems with flooding, and there was redlining going on in Del Ray that had been brought to our attention.

…in addition to the Dip urban renewal, I was given the closeout of the Gadsby Urban Renewal project—which was several hundred million dollars. It’s 12 blocks—the commercial part of downtown Alexandria. Originally it was going up to Washington Street. And it was going back into the neighborhoods. Fortunately that didn’t happen. But the Gadsby project really became King Street. I think if we were doing it today—and hindsight’s always better—it would have been different. There wouldn’t have been as much destruction of some of these old historic buildings…City Hall was part of it and Market Square and all the blocks across the street…