Black Education in Alexandria, Part 3

Black Education in Alexandria: A Legacy of Triumph and Struggle

Black Education in Alexandria

Main page: Black Education in Alexandria: A Legacy of Triumph and Struggle

Part 1: Early African American Education in Alexandria,1793-1870

Part 2: Separate and Not Equal, 1870-1960

Part 3: The Legacy of Segregation, 1954-2023

More Information

Summary: The Legacy of Segregation, 1954-2023

Stripped of their agency by local authorities, Black Alexandrians had to sue the school board to get the City to obey the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board decision and desegregate schools. Ninety years after Black Virginians, Republicans, and Unionists created a constitutional requirement for a system of free schools, 89 years after conservative Democrats required public schools to be segregated and put white authorities in charge, 63 years after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld state-imposed racial segregation, and nearly half-a-decade after the court decided Brown, 14 Black children walked through the doors of Alexandria’s all-white schools on February 10, 1959. It took another fourteen troubled years for Alexandria City Public Schools to fully integrate.

The begrudged integration was not the realization of Alexandria Education Advocate George Seaton’s dream of equality. Instead, Black students found themselves in schools built with more money than their two elementary and one high school, and in classrooms the City outfitted in excess of what their teachers had been given. They were taught by white teachers who did not have the same expectations of them, and they learned alongside children from families who did not think they deserved to be sitting at their desks.

Alexandria Superintendent of Schools T.C. Williams and the school board continued to stonewall desegregation until his retirement in 1963. Under his successor, John Albohm, Alexandria began to cautiously integrate. At first, they assigned just a small number of Black children to white schools. Two years later, in 1965, they assigned students to neighborhood schools and when they did, the legacy of enslavement and Jim Crow was revealed in eye-popping poverty among the Black neighborhoods in Old Town. Immediately, white concerns coalesced around a perception that poor Black students would cause the quality of academics to decline and discipline problems to rise.

As the City began to desegregate, white supremacists burned crosses and terrorized Alexandria’s Black community. The perpetrators went unpunished, while Black children at Maury Elementary and George Washington High School had to step over burnt wood and ashes to go to school.

It would not be until the early 1970s that school authorities would desegregate high school students (1971) and completely integrate elementary schools (1973). The last battle conservative white Alexandrians waged and lost was over bussing – in the end, students had to share the burden equally. In response, more than 1,000 white families fled the school system citing the following reasons: low standards, discipline, and safety. Those white perceptions that continue to dominate public school debates to this day are rooted in Massive Resistance to desegregation.

The white community chose not to honestly reckon with the ways the white power structure had historically and systematically:

- disenfranchised established Black educators and the Black community from City Council and the school board;

- took over the administration and operation of Black schools;

- underpaid educators; stole from and then neglected Black school properties;

- required a curriculum that reinforced white supremacy;

- continually denied Alexandria’s Black students a proper high school;

- denied Black students applications to white schools on racist grounds, including “mental maturity.”

The legacy of these past policies resulted in white families demanding special attention and classes for their children, which impacted the education of Black Alexandrians through the turn of the 21st Century.

Authorities reacted by setting up two schools within each building, forcing a majority of African American students into remedial or general education classes with lower expectations, and streamlining a majority of white students into Gifted and Talented or honors courses with higher expectations.

In 1985, after a decade of apartheid education, Superintendent Robert Peebles published test results that documented a significant racial achievement gap. The drastic reversal in student performance from the early 1870s illustrates the impact racism had on Alexandria’s schools.

After the Reagan Administration produced a report on the mediocre state of public education in “A Nation at Risk,” a coalition of politicians, governors, education reformers, and civil rights advocates launched an accountability movement that focused less on trying to make sure educational resources, racial demographics, special education, and money were distributed equally, and more on holding schools accountable for student performance. “Some civil rights leaders felt that ignoring test scores was allowing school leaders to get away with educational malpractice, particularly for minority and poor students. Similarly, many minority parents lost their enthusiasm for the integrationist project and felt that the improvement of educational outcomes mattered far more than whether their child sat next to a white child in school,” according to Douglas Reed, author of The Federal School House.

As the national debate over educational accountability shifted, the demographics of Alexandria were changing. After desegregation, the student body of Alexandria’s schools was a majority Black and low-income. As Alexandria’s white families fled the city to avoid the integration of schools, they were replaced with young white professionals and retired couples. As a result, many in the white community lost interest in the schools or at least weren’t paying attention to them. After the economy crashed in 2008 and many white families returned to the school system, they were shocked by the state of the facilities.

In the same time period, there was an influx of immigrants into the region that continues to change the face of Alexandria’s public schools. The student body has grown more Hispanic and international and less Black and white. This change, combined with the legacy of more than a century of white control of Black education, provides some nuance and context for ACPS’s struggle to reach federal and state expectations.

More recent regime changes have placed Alexandria City Public Schools under the leadership of Black educators who have been making an effort to address a long legacy of historic wrongs in Alexandria schools through both policy and practice.

Brown Decision Shakes Things Up

In 1954, Thurgood Marshall convinced the U.S. Supreme Court that the “separate but equal” doctrine clashed with the 14th Amendment and was unconstitutional. However, the verdict didn’t specify how school systems should integrate. Instead, the court asked to hear further arguments. Virginia’s white lawmakers took advantage of this window over the following two years to mount an offense that would become a regional white supremacy campaign of Massive Resistance to school desegregation.

While the conservatives were scheming, in 1955, economist Milton Friedman provided them with a cache of ammunition in an article, "The Role of Government in Education," applying Tocqueville’s laissez-faire free market philosophy to education. Not a fan of public education, Friedman advocated for giving parents vouchers to help pay for private schools, theorizing that market forces would establish which were best. [Endnote 1]

At the time of the court’s decision, conservative Democrat U.S. Sen. Robert Byrd, a white supremacist concerned with maintaining the racial hierarchy, represented the Commonwealth. While strategizing options to evade desegregation, Byrd and a team of like-minded Virginia lawmakers eyed a loophole – the court order applied only to public schools. They realized they could avoid integration by offering families vouchers to abandon the public schools, and they could use Friedman’s arguments as a shield against accusations of racism.

Duke University Professor and Author Nancy MacLean said Friedman and his allies

“helped Jim Crow survive in America by providing ostensibly race-neutral arguments for tax subsidies to the private schools sought by white supremacists. Indeed, to achieve court-proof vouchers, leading defenders of segregation learned from the libertarians that the best strategy was to abandon overtly racist rationales and embrace both an anti-government stance and a positive rubric of liberty, competition, and market choice.” These arguments are still being used by voucher proponents. [Endnote 2]

In May 1955, the U.S. Supreme Court issued Brown II and ordered schools to integrate “with all deliberate speed.” However, the language was vague and prioritized the “rights and preferences of white parents by enabling delay,” according to the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). [Endnote 3]

On February 25, 1956, Byrd mobilized his troops and launched a campaign of Massive Resistance.

Within weeks, and in coordination with Byrd, Virginia Congressman Howard Smith introduced the Southern Manifesto that directed states to resist Brown at all costs. In it, lawmakers claimed the Supreme Court had overreached. They also made the all-too-familiar “Lost Cause” argument that the federal government had interfered with states’ rights. Every member of Virginia’s congressional delegation signed the document. [Endnote 4]

The University of North Carolina Historian Karen L. Cox has illustrated how decades of schooling based on “Lost Cause” revisionist history prepared generations of Southerners to engage in and carry out Massive Resistance. [Endnote 5]

“Millions of white parents nationwide acted to deny Black children equal education by voting to close and defund public schools, transferring their children to private, white-only schools, and harassing and violently attacking Black students while their own children watched or participated,” stated EJI in a report on Massive Resistance.

White Virginians were no different.

Early in 1956, Virginia passed legislation that gave parents “freedom of choice” vouchers to send their children to private schools. This drew a reaction from NAACP Lawyer Oliver Hill, who had worked on the Virginia case that was folded into Brown.

“No one in a democratic society has the right to have his private prejudices financed at public expense,” Hill said, piercing the thin veil Byrd and others had hoped Friedman provided. [Endnote 6]

The legislation employed additional tactics to avoid desegregation, including the creation of a three-person board appointed by the governor to assign pupils to schools and handle transfer requests, and a promise to pull funding from, and mandate the closing of, any school that desegregated – even if they were ordered to do so by federal courts.

It took several years for all of the laws associated with Massive Resistance to be challenged and wend their way through the courts, but eventually, each tactic was deemed illegal.

Massive Resistance in Action

In 1956, the governor closed nine schools in Warren County, Charlottesville, and Norfolk to prevent them from integrating. But what happened in Prince Edward County took Massive Resistance to a new level. To avoid a court order to desegregate in May 1959, the county opened private schools for white students using the vouchers and tax credits to cover the cost. More than 90 percent of the white students enrolled. More than 2,200 Black children didn’t have a proper education for five years - those who could afford to move did, others left their homes to live with friends, relatives, or volunteers in the North, breaking up families. Those left behind were unable to overcome the deficit in their schooling. The Supreme Court ruled that vouchers were illegal and forced the county to open the public schools. In 2004, philanthropist John Kluge and the Virginia Assembly set up a scholarship for the adults, now in their 50s and 60s, to further their schooling. However, that didn’t address the needs of their children and grandchildren, who grew up with parents lacking education. Education experts point to parental education level as significant for student success. The Assembly rectified this legacy in 2023 by extending the scholarship money to descendants.

Alexandria Stalls and Delays

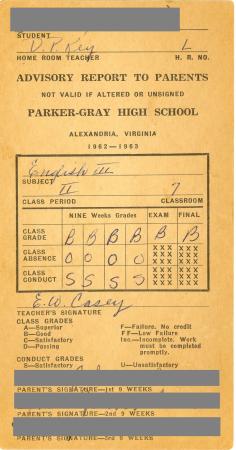

Committed segregationist T.C. Williams and the Alexandria School Board hid behind the state’s threats to close schools and used the Pupil Placement Board to avoid integration. During those years, Black students who wanted to transfer to a white public school had to sit for a test to prove their academic abilities. Their scores, along with their applications, were sent to the state placement board for adjudication.

The school officials’ strategy worked until 1957, when Black parents of 14 students whose applications were denied took the Alexandria School Board to court to compel them to admit their children to the white schools. Over the next academic year, the NAACP represented the families in court. [Endnote 6]

Just before the trial was set to begin, the School Board announced they had developed a “race-neutral” evaluation for transfer requests. Each applicant would be considered against six criteria – none of which used the word “race” but all of which were subjective, giving board members power to control each school’s enrollments.

Judge Albert V. Bryan delayed his ruling on the 14 students’ case until January 1959. He wanted to see how Virginia’s Supreme Court ruled on the state’s student assignment plan. This time out gave Alexandria’s school authorities an opportunity to apply the new rating system to the transfer requests. [Deeper Dig 1]

On January 19, 1959, the Virginia Supreme Court struck down part of the state’s student assignment plan.

Just three days later, the Alexandria School Board boldly denied all 14 applications based on their subjective new criteria.

On February 4, Judge Bryan ruled against the school board, finding that the students were denied admission due to their “race.” He forced Alexandria’s officials to honor the transfers.

The school board appealed and lost.

On February 10, 1959, for the first time, Black children walked through the doors of Alexandria’s all-white schools. [Deeper Dig 2,3]

Williams continued to stonewall and took to evaluating each transfer request on a case-by-case basis, examining each candidate against the six criteria. From 1959 to 1962, only 75 applications were considered and just 16 transfers were approved. Alexandria denied the rights of 59 students during those three years. [Endnote 7]

The Big Test

One of the most common excuses the school board used to deny transfers was the Black child’s inability to compete academically – they used terms such as “mental maturity.” As Alexandria continued to engage in an effort to deny an education to the Black community, officials decided to test all rising first-grade students to see if they were ready for classes. They assumed there would be a glaring “achievement gap” between white and Black children that could be used to justify segregation. They were wrong.

The first test was administered in the summer of 1959 by white psychologists. Fearing they would help their students, Black teachers were under strict orders during testing. [Endnote 8]

The results of the test revealed a number of white children had “quite low” abilities. Shocked, the school board retested all the failing students and created “readiness classes” for any student whose mental maturity was below 4.5 years old.

“Of the 130 students who eventually enrolled in readiness classes, 85 attended all-Black schools….While the effects of delaying entrance of students into first grade fell disproportionately on African American students, white students from a few schools were amply represented in the readiness classes, with over half of the forty-six white students coming from three schools alone.” [Endnote 9]

Williams was obsessed with the white underachievers. He saw their unpreparedness as a “contagion” that could harm the education of other white pupils. In 1960, Alexandria tested every student – roughly 14,000 children – and 714 elementary students and 317 high school students were deemed “irregular.” [Endnote 10]

The distribution was again among both white and Black students. In fact, the all-Black fifth-grade class at Lyles Crouch Elementary School scored higher than all their peers across the city, according to Mable Lyles' book, Caught Between Two Systems.

Of the students who were considered “irregular,” 280 were placed in courses specifically for “mentally retarded” students. Williams had them all retested after which it was decided only 23 students would be put into “mentally retarded classes.” Still, more than 700 elementary school children were placed in remedial courses at 11 Alexandria schools.

“While the purging of underachievers disproportionately affected African Americans, whites constituted the numerical majority of students assigned to the remedial irregular classes.”

At that time, many of Alexandria's Black children were living in low-income families. Modern research on kindergarten readiness has shown that fewer than half of low-income children are ready to start school, as opposed to 75 percent of moderate- and high-income children. In addition, children exposed to trauma, abuse, neglect, divorce, the death of a parent, or domestic violence are much more likely to struggle with school, according to a 2019 study by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The school board’s efforts to use readiness testing to limit integration ended up exposing white parents to some unexpected truths about their children. But more importantly, it led to the establishment of remedial education in Alexandria’s schools, opening a route that would be used to legally continue segregation. [Endnote 11]

City Moves a Poor Black Community to Make Way for a White High School

Around the same time, the Alexandria School Board was planning a new $3 million high school to serve 2,000 white students in the mostly wealthy Seminary and Quaker Lane area. In need of 25 acres, in September 1960, the Board chose to forcibly remove an impoverished Black neighborhood known as “Mud Town.” The school division was only able to claim the land because the African American community had established a school there.

Douglass Wood, an African American, donated a piece of his land for a school. The local Black community raised $1,000, qualifying them to receive $900 from the Rosenwald Fund and over $4000 in public funds to build a one-room school house. In 1927, the Seminary School for African Americans opened as part of Fairfax County schools. Alexandria annexed the area in 1930 putting the school under the jurisdiction of the school division. This gave Williams and the board the foothold needed to claim the parcel the school was on, but they planned to grab a much larger area and build a school that would bear the superintendent's name.

The Black community fought back and eventually the school board and City Council agreed to set aside seven of the 25 acres for a new subdivision for the displaced Black families.

The End of Massive Resistance in Alexandria

In June 1962, Williams announced his retirement, effective January 1, 1963, ending a thirty-year reign over the schools during which he had “denied educational opportunities to disfavored groups, particularly African Americans and special needs students” on whom Williams did not “wish to waste precious public funds.” [Endnote 12]

In May 1963, the City Council voted to desegregate all public facilities. The new superintendent, John Albohm, hailed from York, Pennsylvania. That summer he began implementing the City’s decision by desegregating school programs, including summer school and night school.

However, Albohm found he had to move carefully – the local regime remained conservative and committed to preserving the “race-based class structure in Alexandria.” White authorities were both racist and classist and were not okay with poor African American children going to school with middle-class white students. [Endnote 13]

Albohm launched programs to tackle racialized poverty and address the legacy of decades of white control that had worn down Black schools and educators. Over time, some of Alexandria’s middle- and upper-class African American families had left the city and the schools. By the 1960s, the number of impoverished Black students attending Alexandria’s public schools had increased significantly. Up until desegregation, white Alexandrians had the luxury of ignoring systemic poverty, but once integration exposed it, they were shocked by its vastness.

Desegregation “meant that the problems of children in poverty became the problems of administrators (and parents) in white schools. The resulting class-based conflict between whites and African Americans produced significant conflict in Alexandria over the purposes and aims of schooling. Many white parents viewed these efforts to address the educational needs of African American students as harming the interests of their own children,” stated Douglas Reed, in Building the Federal Schoolhouse.

This zero-sum perception caused “significant” white flight from Alexandria, “even among parents who labeled themselves liberal,” according to Reed, whose research shows the flight trend was exacerbated ten years later when Federal authorities demanded Alexandria integrate neighborhood elementary schools.

Albohm began to cautiously integrate over the summer of 1963. In consultation with the Virginia Pupil Placement Board, he assigned 60 Black students who had been bussed to Lyles-Crouch to their neighborhood schools. He also asked the principals at Lyles-Crouch and Charles Houston to quietly recommend to parents that their children attend Ficklin and Lee (formerly all-white schools) in the Fall. These were the first moves away from segregation in Alexandria. [Endnote 14]

Federal Progress Encourages Change

In July of 1964, President Johnson signed into law the most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. The Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination in all public places, required the integration of schools and public facilities and made job discrimination illegal at the expense of losing federal funds (Title VI).

That same month, Alexandria expanded the school board from six to nine members and appointed the first Black Alexandrian - Ferdinand T. Day. He would eventually become the first African American to chair a school board in Virginia.

The same year, federal courts decided that “freedom of choice” tuition grants for private schools were unconstitutional. From 1960-1965, Alexandria granted 1,000 vouchers to upper-middle-class white students who used them to supplement the expense of private and parochial schools. Some students were educated as far away as Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Ohio and Indiana. [Endnote 15]

In 1965, the national movement for civil rights and racial equity convinced Congress and the President to protect the rights of African Americans with a Voting Rights Act. The voice of Alexandria’s Black community was finally restored.

That same year, the amount of federal dollars flowing to schools grew with the passage of the first Elementary and Secondary Education Act. The new ESEA, together with Title V of the Civil Rights Act, elevated the Office of Civil Rights within the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. The office was put in charge of desegregation.

An Uneasy Desegregation in Alexandria

In the Fall of 1965, every Alexandria student regardless of race was assigned to the nearest neighborhood school, revealing a concentration of Black students in a handful of schools and exposing more than a century of housing discrimination.

- Lyles-Crouch in Old Town: 100 percent Black student body.

- Charles Houston in Old Town: 100 percent Black student body.

- Patrick Henry serving Seminary area: 100 percent white student body.

- Douglas MacArthur on Janneys Lane: 100 percent white student body.

- James K. Polk serving Seminary area: 100 percent white student body.

[Endnote 16]

Parker-Gray High School graduated its last class in 1965 and reopened the next academic year as a middle school for Black and white students. The other three high schools were integrated based on the new school boundaries, which resulted in:

- T.C. Williams High School on Upper King Street: 12 percent of students were Black.

- George Washington High School in Del Ray: 25 percent of students were Black.

- Francis C. Hammond High School served Alexandria’s wealthiest neighborhoods: more than 90 percent of students were white.

Although Black students were admitted to the formerly all-white schools, they still encountered tremendous racism from other students and their teachers.

Lillian Patterson, former curator of the Alexandria Black History Museum and respected member of Alexandria’s Black community, said that when her daughter began attending a white school in 1965, the white teacher would not honor the top grades given to her by her previous Black teacher. [Endnote 17, Deeper Dig 4]

Research has found that when Black students have Black teachers, they are more likely to graduate and go to college. They are also more likely to be recommended for Gifted and Talented programs. At the same time, they are less likely to be suspended, expelled, or sent to detention. But most importantly, Black teachers have higher expectations for Black students. After Brown, Black students were more often underserved and over-disciplined by white teachers, harming their ability to learn, graduate, and take advantage of higher education. [Endnote 18]

In addition, Alexandria’s Black parents had a difficult time advocating for their children since white teachers refused to speak with them outside of two annual parent-teacher conferences. Not only did they face white hostility from educators, but Black parents were not welcome at the Parent Teacher Association meetings either. The PTAs formed “all-white executive councils” to maintain their control of Alexandria’s schools. Middle- and upper-class white Alexandrians continued to believe that poor Black children would harm the academic reputation of their schools. Many caved under their self-induced fears and left the school system for whiter suburbs or private schools as integration settled in. Horace Mann’s Common Schools philosophy had clearly been overcome by centuries-old colonialism that still infiltrated Southern white culture. [Endnote 19]

Secret Seven

After desegregation began, Alexandria’s Black community found they had to continue to rely on a group of African American men referred to as the Secret Seven to get school officials to do their jobs for their community. This group of Black leaders, who included Ferdinand T. Day, met regularly over the years to discuss community concerns, and find ways to negotiate improvements. Melvin Miller, an attorney and activist who worked pro bono on desegregation cases, was their spokesman.

Tensions Draw Out Racial Terror

In 1969, a large protest over police brutality grew out of an altercation between a white policeman, Officer Claiborne Callahan, and a group of Black teens who were playing basketball. Callahan arbitrarily ordered the youth to go home, but the boys refused to go. In response, the officer pistol whipped one young man, Keith Strickland, who lost consciousness. When the officer wasn’t disciplined, more than 150 Black Alexandrians marched to City Hall to demand accountability.

That fall, Friday night football games were canceled after a spate of incidents involving firebombs, racist vandalism, and rock throwing on the grounds of George Washington High School (GWHS).

Then on Friday, May 29, 1970, Robin Gibson, 19, was killed by a white storekeeper at a 7-Eleven near Lynhaven in North Alexandria. He was not armed and had done nothing wrong.

For three nights, Black youth gathered and protested while older community members urged them to remain peaceful. Some engaged in vandalism and rock throwing. Some started fires. No one was seriously hurt and at least 10 Black people were arrested. The Black community was frustrated, according to Urban League Staffer Mark Boston, who told the New York Times, “For the last few years, there have been poor relations between Blacks and the city’s power structure. This killing was the last straw. Now we can hardly control the people because they tried to abide by the system and got nowhere.”

The following Wednesday, the all-white City Council passed an ordinance outlawing firearms and knife sales and small cans of gasoline. They also gave themselves the power to impose a curfew.

On Oct. 23, 1970, the NAACP held its state convention in Alexandria. On opening night, flames from a burning cross reflected in the windows of Maury Elementary School.

A few weeks later, white supremacists gathered around a burning eight-foot cross at GWHS. After leaving the high school, the mob torched another cross at Maury Elementary School. The next school day, Black students had to step over charred remains of the wooden crosses to attend classes to take advantage of their right to a free and adequate education. Alexandria police failed to hold anyone accountable for these acts of terrorism against the Black community. [Endnote 20]

In November, white supremacists picketed in front of Superintendent Albohm’s home. They called him a “traitor to the white race,” who was “aiding Black terrorists” in Alexandria’s schools.

In his book, Reed writes about a school event where a white student called the Black Homecoming Queen a “n- - - - r” to rousing cheers. The white students heckled her and demanded she step down. Then a fight broke out.

GWHS white parents put the blame not on racial terror, but on the lack of discipline at the school. They told a Washington Post reporter that safety was their main concern. They said desegregation had brought too many discipline problems. “Everything would fall back into place if we could get discipline back into the schools,” they said. [Endnote 21]

The problem wasn’t disciplinary. The problem was racism. Many African American parents and students were fed up with school policies that used race-neutral language while maintaining racial hierarchies.

White and Black community members continually clashed over school discipline and school quality until the two issues came to define integration. [Endnote 22]

It wasn’t long before a few school board members tried to fire Albohm over the dual perceptions that there were lower achievement levels and a breakdown of discipline.

Between burning crosses, angry white parents, and school board defectors, Albohm surrendered and gave teachers the authority to expel students permanently from their classes. The new subjective and unappealable power was written into teacher contracts in 1971.

“Repressive,” is what Black City Councilman Ira Robinson called it. Robinson criticized the schools for failing, ignoring and neglecting Black students. He denounced teachers for labeling Black children as disruptive in order to kick them out of school. And he chided them for passing students to the next grade without having taught them. [Endnote 23]

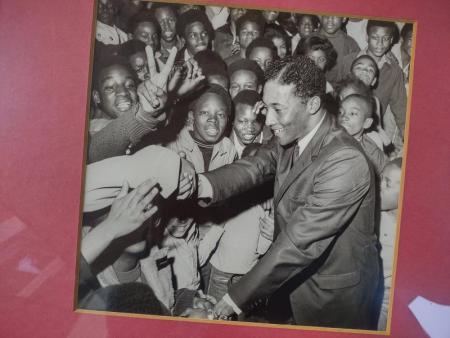

Photo courtesy of McArthur Myers

Alexandria’s Black youth were clearly being denied their right to an adequate education and they knew it. In late March 1971, Black student leaders at George Washington High held a series of all-day discussions. The students developed a list of demands for local officials to consider. They asked for a Black principal, more Black teachers, classes on Black culture and for the school to relax the strict code of discipline. Many of the students who skipped classes to attend the organizing sessions were suspended by the white school authorities. When students met again without permission, the white principal threatened to suspend them and was subsequently assaulted by a student. That night, at least 100 white people held a meeting in Rosemont and called for a crackdown on discipline at GWHS.

Albohm told reporters that the problems at GW were the result of frustrations in both communities. “Blacks remember when their children dominated the athletics, social events and prizes at Parker-Gray and whites believe their high school has declined from standards of excellence in achievement,” he said.

The solution, he and the board decided, was to reorganize middle and secondary schools by fully integrating upper school students first. Officials knew that “wholesale elementary school integration - would accelerate white flight.” To avoid that, they hatched a plan that kept neighborhood-based junior high schools, sent students to ninth and tenth grades at GWHS and Hammond High, and brought all 11th and 12th grade students together at T.C. Williams High School. [Endnote 24]

Remember the Titans

The new approach was implemented in the Fall of 1971 and the resulting racially mixed Titan football team had the benefit of varsity talent from all three high schools. That fall, they handily won the state championship and along the way, brought Alexandria’s white and Black communities a little closer together.

Director of Secondary Education John Stubbins told the Washington Post, “It’s pretty obvious that there’s been a tremendous spillover into the entire system because of that team…. The parents are thrilled to death to see these kids getting along and it's really helped. A lot of minds have been changed at the dinner table, believe me.”

But that spirit didn’t translate to communities surrounding extremely segregated neighborhood elementary schools or to Hammond and George Washington where racial clashes were constant. [Endnote 25]

Bussing Battles

Under more federal pressure to integrate all grades, Albohm prepared for systemwide desegregation. That meant changing neighborhood boundaries and it meant bussing students. Critics from both communities were unhappy with him.

White parents who wanted to keep their segregated neighborhood schools through the current boundaries joined the Alexandria Committee for Quality Education. The anti-bussing group didn’t want to waste taxpayer dollars on a “sociological experiment.” [Endnote 26]

In a letter to the Washington Post, the group’s founder Donald Baldwin, a GOP lobbyist and member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, wrote, “The reorganization of Alexandria’s secondary schools last year to achieve racial balance is not working. The quality of education in our public schools has gone down, and no one is happy with it - blacks or whites.” [Endnote 27]

The Black community wanted to redistrict, but they also had issues with bussing. “The weight of bussing is going to fall on the poor Blacks of this city,” Melvin Miller said.

The NAACP threatened to sue.

In the end, Albohm incorporated most of the NAACP’s proposals, including pairing elementary schools and boundary changes. The final plan bussed white and Black children equally, allowing the City to avoid a federal lawsuit. It was adopted and with the help of citizen groups Alexandria started desegregating schools in earnest in 1973, according to Mable Lyles. [Endnote 28, Deeper Dig 5]

But not all the white parents were helpful. Baldwin filed a lawsuit in an attempt to halt the integration plan on August 27, 1973. He and 11 parents, who made up the Committee for Quality Education, failed in their bid. The suit was never heard by the courts, which ruled there had been adequate public deliberation on the bussing plan. [Endnote 29]

The summer after Alexandria implemented bussing (1974), 1,039 white students left ACPS. Their families either moved or put their children in private schools. Three elementary schools lost 40 families to private schools. The parents weren’t shy about why they left, telling ACPS surveyors that integration had harmed the quality of education in the public schools, using language such as, “low standards,” “discipline,” “safety,” and “racial issues.” [Endnote 30]

The proportion of Black students in Alexandria schools jumped from 31 percent in 1971 to 52 percent in 1976, solely because of white flight. [Endnote 31]

The Legacy of Desegregation

White parents' reactions to desegregation, based on racist and classist perceptions that were not supported by data, cleaved the education system in two. In the same school buildings, educators provided both racialized special needs assistance and Gifted and Talented programs - resulting in vastly different educational experiences and expectations for Black and white students.

By 1980, Black Alexandrians made up less than a quarter of the city’s population while Black public school students made up nearly 60 percent of ACPS enrollments. As a result, school officials expanded the Gifted and Talented programs and did everything they could to entice and keep white students at the public schools. [Endnote 34]

Gifted and Talented

In the fall of 1973, the year Alexandria finally desegregated its elementary schools, the school division applied for federal funding to develop a Gifted and Talented program. The previous June, only four students in Alexandria had been identified as “gifted and talented” and one of them attended private school. In the application, the school admitted they hoped the program would reduce white flight. [Endnote 32]

In the first years, the majority of the students identified as academically gifted (not musical or art) were white. By 1981, the program included 14 percent of all fourth through sixth grade students in the city, but 83 percent of the students were white and just 12 percent were African American (with five percent identifying as other). [Endnote 33]

The Gifted and Talented program “served to further segregate students within schools and became a form of de facto racialized tracking of students, which only further expanded a black-white test score gap,” according to Reed.

The Impact of the Reagan Years

President Ronald Reagan, whose children attended private schools, was no fan of public education. Reagan campaigned on getting rid of the Department of Education and advocated for vouchers for families to send their students to private schools, as well as tax breaks for wealthy parents whose children were enrolled at private institutions. Reagan’s budget proposals continually cut spending on schools. [Endnote 35]

In 1981, Reagan appointed Terrel H. Bell to be Secretary of Education with the expectation he would dismantle the department. While Bell didn’t eliminate the federal agency, he did usher in significant change to the nation’s schools based on a report he commissioned. Bell established The National Commission on Excellence in Education in August of 1981, and tasked the panel with investigating the state of the nation's schools. He wanted to address “the widespread public perception that something is seriously remiss in our educational system.” [Endnote 36]

Twenty-seven years after the Brown decision, the commission was specifically charged with “assessing the degree to which major social and educational changes in the last quarter century have affected student achievement,” a reference to white perceptions that desegregation negatively impacted the quality of schools. [Endnote 37]

The final report, published in 1983, characterized the nation's public schools as centers of mediocrity. America's students, it claimed, could not compete with their peers around the world.

President Reagan called “A Nation at Risk” a wake-up call.

In more recent years, it has come to light that the study's authors went into their research with a set of predetermined outcomes.

An instigating reason for the report was a decline in student scores on national tests, such as the SAT. But the report didn’t take into account the context around falling SAT scores, such as that more youth were going to college than ever before. In the 1950s and ‘60s, very few Americans went on to higher education. Those who did were mainly white male students at the top of their class. However, by the 1980s college was more accessible to all income levels. Culture had changed too, making college an expectation after high school graduation as opposed to immediately entering the workforce. This meant many more students of varying abilities, both sexes, and multiple ethnicities were taking college entrance exams than had been mid-century – the years being used as a baseline. [Endnote 38]

In 1990, the Department of Energy conducted an analysis of test score trends. The resulting Sandia Report contradicted A National at Risk by finding improvement across the board. The Sandia authors broke the test results down by subgroups - men, women, African-American, Hispanic, white, and low-income, and they found that most of the groups were improving over time on the high-stakes standardized tests.

Another fact ignored by the authors of “Nation at Risk:” The nation’s top students were actually ahead of their international peers when it came to academic achievement.

In 2018, National Public Radio reporter Anya Kamenetz interviewed two “Nation at Risk” authors, who cast doubt on the findings that have driven education reforms for the last four decades. They said the panel,

“never set out to undertake an objective inquiry into the state of the nation’s schools. They started out already alarmed by their perceived decline in education, and looked for facts to fit that narrative.” [Endnote 39]

While the report was written in apocalyptic terms in order to grab the public’s attention, the findings simply weren’t true, according to education professor and author James Guthrie, who wrote “A Nation At Risk Revisited: Did 'Wrong' Reasoning Result in 'Right' Results? At What Cost?”

Guthrie told NPR, the commission was “hell-bent on proving that schools were bad. They cooked the books to get what they wanted.”

Back in Alexandria

In 1985, Alexandria administered a standardized test developed by the education publisher Science Research Associates. The disaggregated results identified a glaring gap – white high school students scored at the 75th percentile in reading, math and language arts. Black high school students scored at the 27th percentile in the same subjects.

This drastic reversal from the early days of public education in Alexandria, when Black students were taught by experienced Black instructors and outscored their white peers, illustrates the impact racism has had on education in Alexandria.

“Alexandria public schools are designed to educate white students. The board responds to the needs of white, upper-class students,” said Melvin Miller, who was also spokesman for the Urban League of Northern Virginia, in reaction to the test scores.

Miller called for the establishment of a community task force, as well as more tutoring and prioritizing of Black youth.

But many in the white community continued to blame poverty, not the accumulation of years of racial discrimination.

“It is unfortunate we still have vestiges of the old days and the old ways in Alexandria. Some Alexandrians, both black and white, still assume that poor kids – black poor kids, specifically – cannot learn; that they cannot succeed in school. This must change…We must assume that every child can learn,” said Superintendent Robert Peebles, who was white.

Black Alexandrian John Smith, a staffer on the U.S. House Committee on Education and Labor, blamed low expectations, not poverty. He said that in other parts of the country where students are treated the same, regardless of class or ethnicity, they see different outcomes.

“When a ghetto kid and a white kid walk in the school door, they are treated equally. The same is expected of both of them,” Smith said, echoing the original theory embedded in the Common Schools Movement.

The Standards and Accountability Movement

Expecting the same effort and outcomes from all students was the foundation upon which the Standards and Accountability movement was built. In a follow up to the 1983 “Nation at Risk” report, in 1989, President George H. W. Bush and Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, who headed up the National Governors Association, held an education summit and invited governors and business titans.

At the summit, governors committed their states to setting expectations for what students should know and be able to do before advancing to the next grade or graduating. These standards were tested by each state in certain grades – such as 4, 8, 10 and 12 – to ensure the material in the standards was being taught in the classroom.

Throughout the 1990s, states worked on setting standards and assessing them. Virginia produced the Standards of Learning and used SOL tests to make sure educational milestones were met.

No Child Left Behind and Civil Rights

In 2001, when reauthorizing the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, Massachusetts Sen. Ted Kennedy and Ohio Rep. John Boehner worked together on what would become President George W. Bush’s signature legislation - the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB).

The law was meant to help students by shining a light on the schools that were failing them. The system would be held accountable for teaching all students by requiring states to test student knowledge of grade-level standards each year in grades 3-8 and once in high school, and break the scores down by ethnicity, income, and English Learners. NCLB changed the use of tests to measure whether standards were being conveyed to and learned by students into a high-stakes annual indicator of school and community success or failure. If results identified declining test scores or gaps between groups, then states were required to label the schools as failing. States were to offer resources and schools were to generate improvement plans or be taken over by higher authorities. In an attempt to keep expectations high, the law gradually ratcheted up the percent of students who needed to reach proficiency on the state test through the year 2014, when all public school students across the nation were expected to perform at 100 percent proficiency.

Secretary of Education Rodney Paige, the first African American to serve as U.S. education chief (2001-2005), said the achievement gap was the most important civil rights issue of our time. He argued the new federal law would finally deliver on Brown vs. Board’s promise to provide equal educational opportunities to Black students.

The Impact of Testing

Developing and scoring tests is expensive and the federal government never came close to fully funding the mandates they set up with NCLB. States tended to rely on affordable contractors which translated into standardized multiple-choice tests, instead of criterion-referenced, or short- and long-answer tests. Many education experts didn’t believe annual testing was necessary to ensure the standards were being taught, suggesting that testing in benchmark years had worked in the past.

Teachers’ unions were being blamed by some for corrupting the schools and allowing ineffective teachers to continue to hold positions. The law addressed this by holding teachers accountable for students who didn’t score proficient. Annual NCLB testing, called annual yearly progress, summed up an entire year of classroom instruction in a single multiple choice test score without nuance or context. The results were made public. Teacher morale sank.

NCLB Failed to Close the Gap

Wharton School of Education Professor David Hursh argued in Race, Ethnicity and Education that the law failed to close the achievement gap, and in urban schools with minority-majority student bodies it exacerbated inequalities.

Hursh, an expert in curriculum, said that NCLB ignored students who weren’t middle-class and caused more inequality. Schools were blamed for the government’s failure to establish an equal society.

“NCLB, with its emphasis on efficiency and individualism, diverts attention away from the social issues that need to be solved if we are to really improve education outcomes and close the achievement gap. Neoliberal governments, such as in the United States, desire to reduce public funding for education and other social services and, where possible, privatize social services and submit them to market pressures,” according to Hursh.

Public schools have been disliked and barely tolerated by conservatives since they were first forced to open them under the 1869 Constitution, an agreement written by self-emancipated Blacks, Unionists and Republicans that Virginians had to agree to in order to rejoin the United States. It was replaced in 1902, with a new constitution written solely by white conservative Democrats with the sole purpose of disenfranchising Blacks. In it, they baked racial hierarchy into the system by enshrining the segregation of the state’s public schools. They were as driven by their colonial Protestant values as the authors of the 1869 Constitution were committed to the ideals of the Common Schools movement.

Another Loophole

NCLB fell into the same loophole as Brown – it too only applied to public schools. Private schools were not and are not required to test their students and report the disaggregated results to the state Department of Education. There are no scores to be made public allowing for comparisons with the public schools. Private schools were not and are not required to ensure their teachers are of “high quality” with higher degrees in the subjects they teach. They are not required to show their students are graduating on time. Private schools are not compelled by law to provide special education service to their students. Private schools are not held accountable by the federal, state or local governments in any way because they are private and do not use public dollars to fund their operations.

A consequence of aggressive annual testing and reporting for just one part of our education system - public schools - has been an increased perception that public schools are failing. However, it would be helpful to be able to balance public school testing data with private school results – disaggregated by income – to get a clearer picture, even though private schools are able to select their student body while public schools accept all students regardless of income or ability.

Changing Demographics & Politics

As conservative families left Alexandria to avoid integration, they were replaced with young professionals and retirees. One hundred years after conservative Democrats took over city politics, their one-party, white-supremacist rule ended in 1971. They were replaced by Republicans and progressive Democrats and the City Council grew increasingly liberal. African American concerns were finally on the table and the majority of city residents looked favorably upon government services.

Vola Lawson, who was City Manager from 1985-2000, said, “When we moved here in 1965, Alexandria was a sleepy Southern town, very much a stronghold of the Byrd machine. And it was wonderful to live here during the next several decades because during this period of time, the city really changed into one of the most progressive places in the state of Virginia.” [Endnote 40]

Black Alexandrians gained influence over the 1980s and ‘90s. At the same time, immigrants – many from Central America and Ethiopia – settled in West and North Alexandria. The new communities often didn’t speak English as their first language and Alexandria schools were initially slow to provide services for their children. In 2023, ACPS had more Hispanic students than Black or white.

Set up for Failure

On July 18, 2003, the principal at T.C. Williams High School, John Porter, testified before Congress about the impact NCLB was having on Alexandria’s schools. At the time, the city had one high school that served 2,000 diverse students, nearly half of whom were from low-income families. The majority were African American (44 percent), 34 percent were born in another country (representing 70 different countries), and 22 percent were white.

“Such ethnic and socioeconomic diversity is certainly a strength for our students and our community, but also presents many challenges related to addressing teaching and learning for our students. One of the most immediate challenges relates to foreign students and standardized testing. I have read research that indicates an individual needs to be fully immersed in a language for five to seven years in order to truly have the language skills necessary to perform on a standardized test. I am concerned about how many of our foreign-born students, solely as a result of language barriers, will drop out of school instead of stay in school. While the NCLB requirements are well intended, these students must be provided with adequate supports in order for them to achieve. We want all of our students to leave us with the knowledge and skills necessary to lead productive lives in whatever direction they choose,” Porter said. [Endnote 41]

In the first decade of the 2000s, T.C. Williams High School was considered a “persistently lowest-achieving school” and the federal government ordered it to “transform.” It has been difficult for Alexandria to overcome the fact that all students, even those who are brand new to the school or the country, must be tested and hit performance targets.

“The accountability structure of NCLB effectively made it nearly impossible for schools with high percentages of English-language learners to make” AYP, wrote Douglas Reed, before adding, expecting schools to demonstrate yearly growth in proficiency for “a subgroup which is, by nature, annually repopulated by students at lower levels of achievement is to set that school up for failure. As one scholar put it, even with the best resources, there is not much chance of improving the AYP indicator of the Limited English Proficient subgroup over time.” [Endnote 42]

State Threatens to Take Over Jefferson-Houston K-8 School

In 2003, Jefferson-Houston, a K-8 school on the West side of Old Town, failed to make Annual Yearly Progress as required under NCLB and Virginia. Over the next ten years the school didn’t meet the testing benchmarks and became one of four Virginia schools eligible for a state takeover.

Many blamed a redistricting plan from 1999 that increased the number of poor and minority students assigned to the school. Black parents from the Charles Houston neighborhood had pushed back against moving their children from George Mason elementary, but they didn’t win. Jefferson-Houston became a primarily low-income African American school. High turnover among the staff and leadership continued to exacerbate the school’s problems. After two years of failing test scores, parents were given the opportunity to send their children to other area public schools, as required under NCLB. But this meant that better-achieving students left behind those struggling the most, perpetuating a cycle of failure at Jefferson Houston. [Endnote 43]

Student performance continued to dive until 2013, and the school lost its accreditation. After avoiding a state takeover, Alexandria officials rebuilt the school facility and reopened it in 2014, but test scores remained too low to meet benchmarks that had been ratcheting up toward 100 percent proficient (NCLB’s 2014 goal). In 2015, the school offered the International Baccalaureate program in an attempt to reform and revamp the school's image. [Endnote 44]

Richmond Changes Accountability Requirements

Beginning with Republican Gov. Robert McDonnell’s tenure (2010-2014) Virginia has been loosening the grip test results have on school accreditation. Under McDonnell, VBOE lowered the cut score needed to reach proficiency on the Standard of Learning Tests because, the Board said, they designed a more rigorous test. At the same time, more and more superintendents were lobbying Richmond to reduce reliance on test scores.

Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D) (2014-2018) continued the trend. During his tenure, Congress reauthorized the school funding bill in 2015 and gave states more leeway to decide how to deal with schools that fail state tests. The new law no longer required Richmond to consider student scores when evaluating teacher performance.

Gov. Ralph Northam (D) followed McAuliffe, and his administration tied accreditation to reducing achievement gaps, but they did so by incentivizing improvement and recognizing growth in student learning.Under these expectations, Alexandria City Public Schools, with significant diversity and poverty, began to hit their targets. In 2019 every Alexandria school was fully accredited.

Alexandria’s Majority Minority High School

By 2020, Alexandria’s one high school was a minority majority school. Students were from 119 countries and spoke 125 languages. The majority of students at ACHS were Hispanic (37.7 percent); Black and white students each shared around a quarter of the student body. The school hosts an International Academy where students from around the world, many of whom are English learners, attend classes. The diversity and mobility at the high school generally translate into lower standardized test scores. On another indicator, on time graduation rates, the school is close to hitting the state average.

In 2021, despite being the second year of the COVID pandemic, ACHS saw its highest graduation (90 percent) and lowest dropout rates since Richmond began reporting the data (2008). The largest gains were made by Hispanic and low-income students. The statewide graduation average was 93 percent. To break that down further:

- 98 percent of white students graduated (state average 95 percent),

- 93 percent of Black students graduated (state average 91 percent),

- 84 percent of Hispanic students graduated (state average 85 percent),

- 90 percent of English Learners graduated (state average 77 percent), and

- 88 percent of economically disadvantaged students graduated (state average 89 percent).

In 2022, 86 percent of ACHS students graduated on time (state average 92 percent). The school was accredited by the state with conditions. Black, low-income, Hispanic, and students with disabilities needed to bring up their math scores on the SOLs for the high school to gain full accreditation without conditions. [Endnote 45]

Photo by Michelle Rief

At the time, Dr. Gregory Hutchings, Jr. was the superintendent, a Black leader who graduated from the high school when it was still called T.C. Williams. When the City considered whether to build a second high school to deal with a growing student body, Hutchings fought to keep just one unified school because he was concerned, in light of Alexandria’s history, that two would breed inequity. He supported students who led the charge to change the name of the high school from T.C. Williams to Alexandria City High School. Hutchings also led ACPS through a planning process that resulted in a strategic plan in which racial equity was placed at the center of every decision the school division makes.

High School Students Reject T.C. Williams Moniker

In 2021, students in the Black Student Union, Minority Student Achievement Network and a group called Rename T.C., led a campaign to change the name of T.C. Williams High School. After educating the community about T.C. Williams' history as a conservative white supremacist whose actions harmed the Black community, the school was renamed Alexandria City High School.

In many ways, Hutchings said, “Alexandria is more open to equity ideas than other school divisions around the country and state, which have seen heightened tensions and conflict in recent years.” [Endnote 46]

Hutchings resigned suddenly in June of 2022. He did not initially give a reason. However, he had come under heavy criticism for not opening schools sooner during the pandemic and for asking school board members to avoid publicly discussing an off-campus fatal stabbing of a student.

Studies have found that the longer schools were closed during the pandemic, the worse the learning loss, especially for low-income students and Black and Hispanic children, muddying Hutchings’ legacy. Hutchings left to lead an anti-racist professional development program at The American University.

In 2022, Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin attacked programs focused on equity, and called history courses that spell out the nation’s racial past divisive. In addition to ignoring the regular processes put in place to review and update the SOLs for history, Youngkin, tasked the Virginia Board of Education (VBOE) with tightening up the indicators used to hold public schools accountable – the same ones that were changed since McDonnell’s tenure.

“This broken accountability system fails to provide a clear picture of the academic achievement and progress of our schools to parents, teachers, and local school divisions,” he stated in September 2022. Youngkin, who is an advocate of tax supported vouchers for parents to send their children to private schools, said his goal is for VBOE to create “the most transparent and accountable education system in the nation” – accountability that will apply only to Virginia’s public schools. [Endnote 47]

On May 4, 2023, the Alexandria School Board appointed the first Black woman – Melanie Kay-Wyatt – to be the superintendent of Alexandria City Public Schools.

Alexandria public schools have trod a centuries-long path from vibrant Black schools, to white control, neglect, and atrophy, to new Black leadership that has put the focus on racial equity. The story of Black education in Alexandria doesn’t end here. It has merged with numerous other communities from around the world, who are living and learning together in one public high school. The social and economic diversity of the student body studying under a leadership focused on furthering equity may just be an example of the Common Schools philosophy in action. In that sense, Alexandria’s schools at last reflect the aspirations of the city’s early Black educators and proponents of free schools.

Part 3 Endnotes

Endnotes

- “How Milton Friedman Aided and Abetted Segregationists in his Quest to Privatize Public Education,” by Nancy MacLean, Institute for New Economic Thinking, Sept. 27, 2021.

- Ibid.

- “Massive Resistance,” Equal Justice Institute Report, EJI.org.

- “The Southern Manifesto of 1956, Historical Highlights, History, Art & Archives,” U.S. House of Representatives online history.

- “United Daughters of the Confederacy: Legacy,” Encyclopedia Virginia online historical resource.

- Maclean. It bears noting that after the NAACP’s success with Brown, Black lawyers became a target for angry whites. They formed citizens councils and used their power - their ownership of money, jobs and land, to threaten NAACP members.

- Building the Federal Schoolhouse, Localism and the American Education State, Reed, Douglas S, pp. 40-43.

- Caught Between Two Systems, Desegregating Alexandria’s Schools 1954-1973, Lyles, Mable T., p. 8.

- Reed, p. 132-133.

- Ibid p. 134.

- Ibid pp. 133-135.

- Ibid p..41.

- Ibid pp. 42-43.

- Ibid p. 43.

- Income: Reed 110-113; Schools pp.106-107; and “Lessons from Past Echoing in Schools,” Brigid Schulte, Washington Post, Sept. 1, 2005.

- Reed, pp..53,54.

- Schulte.

- “65 Years After Brown V. Board Where Are All the Black Educators,” Madeline Will, Education Week, May 14, 2019.

- Schulte and Reed p. 45

- Reed pp..60-64.

- Ibid p..68.

- Ibid p..66.

- Ibid p..69.

- Ibid pp..73-75.

- ACPS article, on ACPS website under history.

- Reed p. 92.

- GOP Lobbyist and SCV Membership can be found in Baldwin’s online obituary.

- Reed p. 93 and Lyles pp. 30, 31.

- Lyles p. 31.

- Reed pp. 116-118.

- Ibid p. 124, and “Northern Virginia Minority Population Grew Sharpley in the 1970s,”by Lawrence Feinberg, The Washington Post, March 11, 1981.

- Ibid p. 148.

- Ibid p. 149.

- Ibid p. 128.

- Reagan's Legacy: A Nation at Risk, Boost for Choice, by Sean Cavanagh, June 16, 2004.

- Washington Post, Apr. 5, 1981.

- A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Education Reform, Secretary of Education and the National Commission for Excellence in Education, April 1983.

- “What a Nation at Risk Got Wrong and Right About US Schools,” by Anya Kamenetz, National Public Radio, Apr.29, 2018.

- Ibid.

- “Interview with Vola Lawson, Retired City Manager,” Office of Historic Alexandria, Oral History taken May 21, 2009, also Reed, p.128.

- Statement of John Porter, Principal at TC Williams before the U.S. Senate.

- Reed, 169.

- Redistricting: “Parents Protest Alexandria School Redistricting,” Washington Post, May 20, 1999. High Turnover, “Turning Around Jefferson Houston,” Alexandria Gazette, June 26, 2005.

- “Alexandria IB To the Rescue?” Mount Vernon Gazette, March 19, 2015.

- Virginia School Quality Profiles, Virginia Department of Education.

- “Alexandria School Board Appoints Superintendent,” Washington Post, May 4, 2023.

- “Youngkin School Ratings,” Washington Post, Sept. 23, 2022.

Deeper Dig

- Albert V. Bryan was the son of the man who headed the Alexandria Militia (Alexandria Light Infantry) when Joseph McCoy was lynched in Alexandria on April 23, 1897. His father, also called Albert Bryan, was on the Board of Police Commissioners when Alexandrians lynched Benjamin Thomas on Aug. 8, 1899. The police failed to keep Thomas safe, and no one was held accountable.

- Initially, Blois Hundley, a Black Alexandrian who worked in the cafeteria of one of the schools, planned to join the NAACP’s lawsuit. When Superintendent Williams found out he fired her. Williams was forced to offer Hundley her job back. Hundley moved her family to Washington, D.C. instead of continuing to send her children to Alexandria’s schools.

- The students who first integrated Alexandria Schools were:

- James E. Lomax, 8

- Margaret Irene Lomax, 6

- Patsy Ragland, 15

- James Ragland, 14

- Sarah Ragland, 8

- Katherine Turner, 11

- Sandra Turner, 7

- Gerald Turner, 6

- Jesse Mae Jones, 8

- Marie Bradby

- James Bradby

- Debrah Bradby

- Judy Belk

- Vickie Belk

- Betty Lou and Jo Ann Gaymon

- Caught Between Two Systems, pp.23-24

- Because white authorities wouldn’t allow African Americans to teach white children, after the Brown decision a lot of experienced, highly credentialed Black educators were fired, according to Education Week.

- Under the pairing plan a partnership was made between the five predominantly Black schools with their white counterparts. All kindergarten students would continue to attend their neighborhood schools. Mount Vernon Elementary was racially mixed and did not pair with another school. The Ficklin School was closed. Cora Kelly 1-3 paired with John Tyler 4-6; James Polk 1-3 with Stonewall Jackson 4-6; Maury 1-3 with Lyles Crouch 4-6; Jefferson-Houston 1-3 with William Ramsey 4-6, Douglas McArthur 1-3 with Robert E Lee 4-6.

Researched and written by Tiffany D. Pache for the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project.