Community: The United States Colored Troops (USCT)

Community: The United States Colored Troops (USCT)

Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters US, let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.[i]

Frederick Douglass, Formerly Enslaved Abolitionist, Douglass Monthly, August 1863

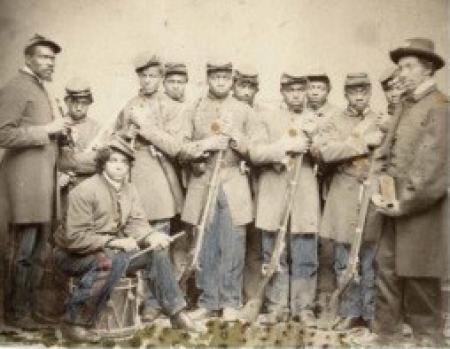

Source: Courtesy of Charles Joyce

In April 1861, when President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 militiamen to fight, enlistment was restricted to any free white male person above the age of eighteen, thereby excluding African American men from service. However, as the war raged on with decreasing enlistments and increasing casualties, the government and the military recognized the necessity for the recruitment of Black soldiers to serve in the Union Army. On July 17, 1862, President Lincoln signed an amendment to the Military Act of 1795 that sanctioned the employment of “as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of this rebellion”[ii] The legislation specifically mentioned labor and camp duty as well as more general military and naval service. A few Black regiments, organized in late 1862, participated in combat operations and helped to show authorities the abilities, determination, and courage of African American men engaged in fighting for their freedoms.[iii]

The Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, explicitly authorized the enlistment of African American men as soldiers.[iv] The following March, the Alexandria Gazette announced their recruitment: “[T]he first drafts at the North will be from the free negro population. All the able-bodied colored men between twenty and thirty-five years of age are to be taken to fill up the ranks of the various negro brigades now under way.”[v] Coordinating and organizing the regiments fell to the Bureau of Colored Troops, established on May 22, 1863, within the Office of the Adjutant General of the Army.[vi] By December, there were reportedly 48,000 United States Colored Troops (USCT) actually in the field, with 106,000 African American men employed by the U.S. Army.[vii] Ultimately, Black men enlisted from every state, totaling more than 200,000 in number, with 5,723 from Virginia.[viii] Nearly one in six Black Virginians who fled from enslavement or who were liberated by approaching Union armies joined the service.[ix] Black troops not only fought valiantly for their own freedom but also challenged the racial profiling of their era, contributing significantly on the battlefields and helping to ensure the success of the Union war effort.

Source: New York Public Library Digital Collection, Manuscripts and Archives Division

African American enlistees from Alexandria may have accounted for more than one-third of those in Virginia. One contemporary account indicates enlistment of 2,000 men from Alexandria alone.[x] The Union Army set up a training center for USCT at Camp Casey just north of the city. With Alexandria serving as a staging ground and supply center, the military government also established hospitals for care of African American soldiers, some of whom were transported from battlefields in Virginia to the city for treatment.

Freedmen’s Cemetery and the USCT in Alexandria took center stage in an incident that draws attention to the unequal treatment of African American soldiers during the war, but ends in a triumph of justice over discrimination in the earliest civil rights action known in the city. Freedmen’s Cemetery initially served as a burial ground for Black soldiers who had succumbed to their illnesses and injuries in Alexandria. More than 400 African American soldiers convalescing in Alexandria’s hospitals protested against this burial location, pointing out that, like white soldiers, they deserved acknowledgement and honor for their service to their country. Their successful petition resulted in the disinterment of approximately 118 USCT from Freedmen’s Cemetery and reburial with full military honors in Soldier’s Cemetery (now Alexandria National Cemetery).[xi]

Triumph Over Injustice and Stereotypes

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. and Britannica.com

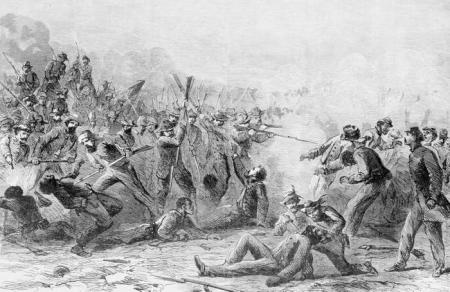

Prejudicial beliefs held by those on both sides of the conflict led to acts of injustice and even violence perpetrated against some USCT individuals and regiments. The worst atrocity took place after the Battle of Fort Pillow in Tennessee with the massacre of 400 USCT who had surrendered to Confederate troops. More routinely, African American soldiers were issued inferior supplies; prevented from advancing into the upper ranks; and subjected to poor camp conditions, substandard hospital facilities, and a shortage of doctors. The fact that Black enlisted men and officers received only $7 per month while white privates earned $13 became a particularly controversial and offensive issue, finally corrected in 1864, at least partially as a result of intervention and protest by the formerly enslaved activist, Frederick Douglass.[xii]

Despite USCT determination to make a mark on the front lines, initial assignments included jobs as laborers, construction workers, and guards on fortifications throughout the Union, including the Defenses of Washington. However, as the war progressed, the need for Black soldiers as a fighting force became inevitable. The USCT rose up to counter injustices and stereotypes about their capabilities with remarkable tenacity and courage in military engagements, distinguishing themselves at the battles of Fort Wagner in South Carolina, Port Hudson in Louisiana, and Nashville in Tennessee.[xiii]

Closer to Alexandria, the greatest number of USCT participated in Grant’s initiatives against Petersburg and Richmond in the Virginia theater during the last two years of the war. One of the most heroic USCT engagements at the Battle of New Market Heights (Chaffin’s Farm) near Richmond resulted in the award of the Medal of Honor to 14 African American soldiers. Heavy fighting by the valorous USCT around Petersburg during the summer of 1864 prompted Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to assert, "The hardest fighting was done by the black troops. The forts they stormed were, I think, the worst of all."[xiv] Ultimately, USCT units took part in every major campaign from 1863 until the war’s end, fighting in 39 major engagements and more than 400 lesser battles and skirmishes. The last regiment mustered out of federal service in December 1867.[xv]

Source: Painting courtesy of the West Point Museum, U.S. Military Academy, West Point, NY

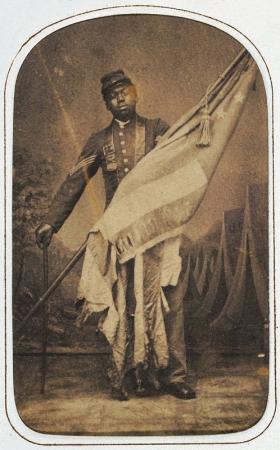

Carte-de-visite of Sgt. William H. Carney, Co. C, 54th Mass. Volunteer Infantry. When the color guard was killed during the July 18, 1863 assault on Fort Wagner (Charleston, SC), Carney seized the flag, marched forward and planted the colors on the parapet. When the Union troops retreated, he struggled back across the battlefield under fierce fire receiving multiple wounds and eventually returning with the flag to his own lines. “Boys,” he said, “I did but my duty; the dear old flag never touched the ground.”

Source: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Garrison Family in memory of George Thompson Garrison

Source: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Garrison Family in memory of George Thompson Garrison

USCT In and Around Alexandria

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Camp Casey, located in what was Alexandria County (now Arlington) north of the city, served as one of the many USCT draft and training centers set up for eager new recruits. At least 16 USCT regiments spent time at Camp Casey, serving as defenders of the Capital or preparing for transport to combat areas.[xvi] Several USCT regiments were recruited in the Washington, D.C. area. These included the 1st USCT Infantry Regiment, organized in D.C.; the 2nd, organized in Alexandria County with its ranks filled by men from D.C. Maryland and Virginia; and the 23rd, raised at Camp Casey.[xvii] The 28th and 29th Infantry Regiments, recruited in Indiana and Illinois, respectively, also trained briefly at the Alexandria County facility before transport to the front. With the war’s end, several units of African American soldiers, including men of the 107th and 4th USCT regiments, found themselves back in the D.C. area on guard duty at the Defenses of Washington.[xviii]

Comprising only ten percent of the entire Union Army, the USCT suffered tremendous losses; approximately one-third of all African American men enrolled in the military died during the Civil War. Given the fierce fighting in the Virginia theater and the proximity of these military operations to Alexandria, many wounded USCT found themselves transported to one of the city’s African American hospitals for treatment. Some succumbed to gunshot wounds and other battle injuries, but infectious diseases and respiratory illnesses caused by unsanitary conditions claimed far more.[xix] Private Adolphus Jacobs of the 23rd USCT wrote from Alexandria: “I have never got over the hurt I received at the Charge at [Petersburg] but I am Well as far as health is Concerned as I ever was.” Unfortunately, Private Jacobs did not recover, though “he stood his Wound as brave as a lion,” according to a fellow soldier who wrote Jacobs’ mother following his death.[xx]

Source: Find A Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com); Memorial Page for Adolphus Jacobs, Find A Grave Memorial no. 67555548, citing Alexandria National Cemetery, Alexandria, Virginia; Maintained by Mrs. Bee (contributor 47112547)

Footnotes

[i] Frederick Douglass, “Should the Negro Enlist in the Union Army?” Douglass’ Monthly, vol. 5, no. 10, Rochester, NY, August 1863.

[ii] An act to amend the act calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions, approved February twenty-eight seventeen hundred and nine-five, and the acts amendatory thereof, and for other purposes, July 17,1862, ch. 201, U.S. Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America, vol. 12 (Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1863), 597-600.

[iii] “Fighting for Freedom,” Fort Ward Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/fighting-for-freedom-black-union-soldiers-of-the-civil-war

[iv] “The United States Colored Troops,” Andre Fleche and Peter C. Luebke, Encyclopedia Virginia

https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/United_States_Colored_Troops_The#start_entry.

[v] Alexandria Gazette, 28 March 1863.

[vi] General Order 143, War Department, May 22, 1863, Orders and Circulars, 1797-1910, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780s-1917, Record Group 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[vii] Alexandria Gazette, 4 December 1863.

[viii] Research conducted in 2010 by the African American Civil War Memorial and Museum in Washington, D.C., into the official records of the Bureau of United States Colored Troops resulted in the identification of records for over 200,000 soldiers; https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/United_States_Colored_Troops_The#start_entry.

[ix] Christina S. Draper, editor, Don’t Grieve After Me: The Black Experience in Virginia, 1619-2005 (Hampton, VA: Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and Public Policy, 2006), 50.

[x] Judge John C. Underwood to William Syphax, Letter, 12 July 1865, reprinted in Alexandria Gazette, 18 July 1865.

[xi] Alexandria Gazette, 10 December 1864 and 8 July 1864; U.S. Colored Troops to Major Edwin Bentley, Surgeon in Charge, at L’Ouverture General Hospital, Alexandria VA, 27 December 1864; J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, to Major General M.C. Meigs, Depot Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General; General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xii] “Fighting for Freedom,” Fort Ward Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/fighting-for-freedom-black-union-soldiers-of-the-civil-war.

[xiii] “Fighting for Freedom,” Fort Ward Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA,https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/fighting-for-freedom-black-union-soldiers-of-the-civil-war.

[xiv] Edward Stanton to Major General Dix, New York 18 June 1864, Summary of Army Intelligence, The Soldier’s Journal, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89038091/1864-06-22/ed-1/seq-6/, cited in “Fighting For Freedom,” Fort Ward Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/fighting-for-freedom-black-union-soldiers-of-the-civil-war.

[xv] "Fighting for Freedom,” Fort Ward Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/fighting-for-freedom-black-union-soldiers-of-the-civil-war.

[xvi] Traceries, Camp Casey, Arlington, VA, Research and Historic Context, prepared for Stantec Architecture, 2019, 4.

[xvii] Fighting for Freedom,” Fort Ward Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/fighting-for-freedom-black-union-soldiers-of-the-civil-war.; 2nd Infantry Regiment, United States Colored Troops Living History Association, http://www.the2ndusctlha.org/mission.

[xviii] Fighting for Freedom,” Fort Ward Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/fighting-for-freedom-black-union-soldiers-of-the-civil-war.

[xix] Edward A. Miller, Jr., “Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in Alexandria National Cemetery, Part I,” Historic Alexandria Quarterly (Alexandria, VA: City of Alexandria, Fall 1998), 5, 6.

[xx] Edward A. Miller, Jr., “Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in Alexandria National Cemetery, Part II,” Historic Alexandria Quarterly (Alexandria, VA: City of Alexandria, Winter 1998), 21.