Community: Humanitarian Aid and the Bureaucracy of War

Community: Humanitarian Aid and the Bureaucracy of War

Do send something, bedding, clothing, shoes, stockings, any poor ones even will be acceptable, warm clothing for children of all ages & necessaries for the sick are very desirable. It appears to me we have no right to any luxuries while such a state of things exists.[i]

Julia Wilbur, Alexandria Aid Worker, to Amy Post, November 1862

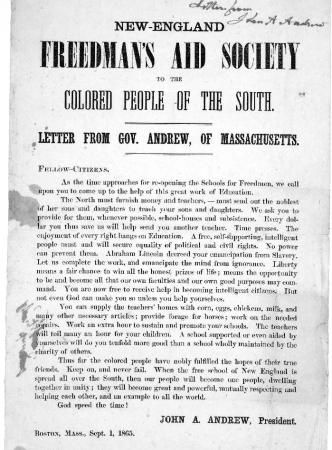

Source: Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Printed Ephemera Collection

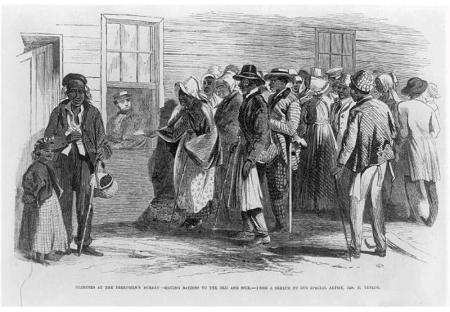

The massive influx of freedom-seekers into Alexandria overwhelmed Union officers, who were not prepared for the humanitarian crisis that unfolded as an unforeseen result of the war. Initially, the government did not provide any dedicated housing, medical support, nutritional provisions, clothing supplies, or educational facilities, and there were few places of worship or burial. The newspapers, particularly the free Black press, painted a dire picture of conditions, urging readers to assist the

thousands of contrabands…in a condition of extremest [sic] suffering. We see them in droves everyday perambuling [sic] the streets…, homeless, shoeless, dressless, and moneyless. And when we think of the cold freezing days of the coming winter…our sensibilities of humanity sink under the dreadful apprehensions consequent upon such direful privations.[ii]

The government could not even begin to address all the needs of freedom-seekers despite the evolving administrative organization and the activities of Reverend Albert Gladwin, a Baptist minister who began working as the Superintendent of Contrabands in the fall of 1862. Moreover, records indicate that official rations and clothing routinely went to the men employed by the government.[iii] The vast majority of refugees, unemployed and predominately women and children, desperately needed assistance and received “no other aid than a daily ration.”[iv]

Northerners, Black and white alike, stepped in to advocate for the freedom-seekers and provide much-needed help. They organized relief societies, raised funds, volunteered in hospitals, established schools, and collected and distributed donated clothing, blankets, and medicine throughout the city’s refugee communities. The National Freedmen’s Relief Association, the Free Mission Society, and other organizations generously provided assistance by forwarding large and valuable consignments of tools and agricultural implements, as well as considerable quantities of provisions and clothing.[v] They also sent teachers for the numerous Black schools appearing throughout the South. Overwhelmingly, the relief workers maintained a philosophy about autonomy and self-sufficiency, emphasizing that wage earners had an opportunity to rise to property-owning independence.[vi]

Quaker Julia Wilbur and formerly enslaved abolitionist Harriet Jacobs achieved recognition for their tireless efforts to provide aid to Alexandria’s freedom-seeking populace. Their diaries and letters provide first-person accounts of the conditions in Alexandria during the war. At times, they found themselves clashing with military and government officials over living conditions of the freedpeople, methods of support, and punitive threats and actions undertaken by the authorities. With relief workers largely gone after the war, aid for the freedpeople as they transitioned to freedom fell to the administrators of the Freedmen’s Bureau, created just one month prior to the end of the hostilities.

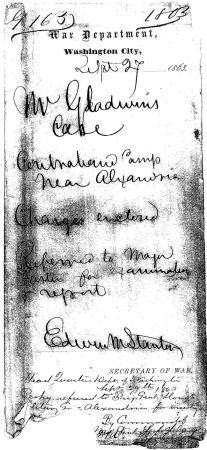

Reverend Albert Gladwin - Government Management

October 1862, Reverend Albert S. Gladwin, a Baptist minister who had arrived in Alexandria several months earlier, began performing the duties of Superintendent of Contrabands.[vii] A Connecticut-born Baptist organizer and fundraiser, Gladwin had spent time raising money for church construction in Rhode Island and then serving as a missionary in overcrowded neighborhoods in New York. Representing the American Baptist Free Mission Society, he arrived in the D.C. area in May 1862, achieving some success in the establishment of schools for freedmen in Washington. Capitalizing on his connections with the provost marshal, Gladwin was officially appointed as Superintendent of Contrabands in Alexandria in early May 1863, and began paid employment for Alexandria’s military government, which had more resources for support than the missionary society.[viii]

Gladwin described his work in his report to the missionary society:

My labors have been incessant from house to house, in looking after their sanitary conditions, clothing, schooling, employment and pay, and funerals at the barracks built for their accommodation and elsewhere.[ix]

Given responsibility for performing weddings and attending to burials of Contrabands and freedmen in the city, Gladwin’s office began production of an important document for historians studying Freedmen’s Cemetery and the history of the Civil War in Alexandria. Titled the Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va., the document (often referred to as the Gladwin Record, hereinafter called the Book of Records) lists the names of Contrabands and freedmen who died in Alexandria, along with their ages, places of death, and sometimes causes of death. The record provides invaluable raw data for genealogists looking for their ancestors, demographers studying mortality, and historians interested in the development of African American neighborhoods in Alexandria.

Julia Wilbur and Harriet Jacobs

We went into many of their [the contrabands’] houses, and were gratified with the appearance of neatness and comfort compared with those of Washington. This improvement we attribute in great measure to the labors of Harriet Jacobs and Julia A. Wilbur, who is from Rochester, New York, whose exertions for these people have been indefatigable.[x]

Report to the New England Society of Friends (Quakers), 1864

Source: Haverford College Library, Quaker Collection, Haverford, Pennsylvania

Julia Wilbur, a Quaker schoolteacher and abolitionist from upstate New York, arrived in Alexandria in early November of 1862 as a Freedmen’s agent on behalf of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society.[xi] Unyielding in her dedicated efforts to procure supplies for the refugees, Wilbur was not averse to seeking the assistance of those who held the power to do something to aid the freedom-seekers, even petitioning “the President of the U.S. on behalf of suffering humanity.”[xii]

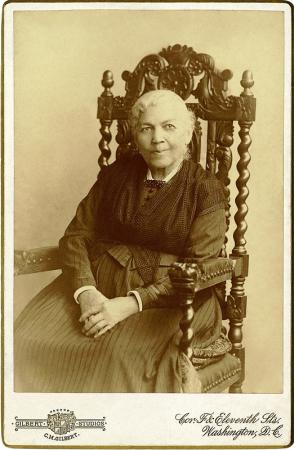

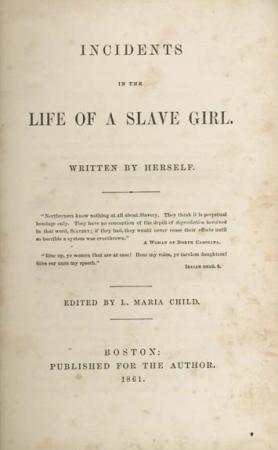

In 1863, Harriet Ann Jacobs joined Wilbur after leaving her adopted home in New York and serving as an aid worker in Washington, D.C. for a year. Jacobs was born into enslavement in 1813, escaped in 1842, and became legally free in 1852 when friends arranged to pay for her manumission. Her manuscript, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published in 1860, became one of the most important narratives of the abolitionist movement, describing nearly seven years of hiding in an attic.[xiii] Jacobs came to Alexandria under the sponsorship of the New York Society of Friends (Quakers) to assist her fellows during the war.[xiv] Like Wilbur, she dedicated herself to improving the lives of the freedom-seekers and described the terrible conditions of the Contrabands’ living situations in which the refugees were “packed together in the most miserable quarters, dying without the commonest necessities of life.”[xv]

By the middle of 1863, Wilbur and Jacobs had moved into rooms in the southern half of a house at 321-323 S. Washington St. The military governor had designated this private residence, abandoned by Confederate sympathizers, for use as Contraband housing in the early years of the war. The northern section eventually became a hospital for Contrabands, while the southern section served as a storage and distribution area for relief supplies and as housing for government and aid workers, like Wilbur and Jacobs.[xvi] Jacobs revealed something of the relationship between the housemates when she wrote, “I had the assistance of two kind friends, women. True at heart, they felt the wrongs and degradation of their race,”[xvii] likely referring in one instance to Wilbur, who often wrote about “Mrs. J” in her diaries for the rest of her life.[xviii]

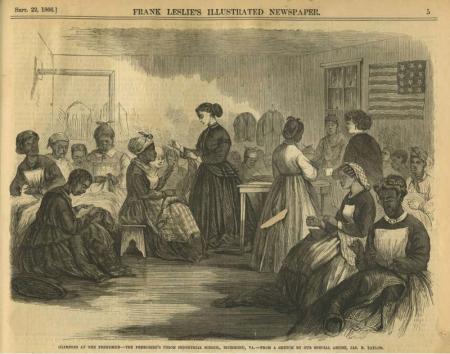

Both Harriet Jacobs and Julia Wilbur worked tirelessly to distribute bundles of clothing, blankets, bedding, and other supplies they had collected from sympathetic supporters. In the first few months of 1863, Wilbur received 33 boxes, barrels, and bales of needed items, while Jacobs distributed more than 2,600 pieces. They set up a sewing school room with four machines, producing almost 7,000 garments for distribution.[xix] In a typical day, Wilbur walked several miles, visiting hospitals, homes of the freedpeople in their neighborhoods, and government barracks, checking on the health of the refugees and distributing supplies.[xx] Jacobs’ concerns also focused on schooling and her commitment to African American people taking lead roles in their own education.[xxi]

Source: Harriet Jacobs. By Gilbert Studios, Washington, D.C. (C. M. Gilbert). Restored by Adam Cuerden. Journal of the Civil War Era. Public Domain; Jean Fagan Yellin, Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, www.docsouth.unc.edu

Source: Documenting the American South, The University Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC; https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jacobs/title.html

Source: Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, Record Group 111, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

A Clash of Values

Source: Office of the Adjutant General Colored Troops Division 1863, Record Group 94, G26-83, Box 15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

In their advocacy, Jacobs and Wilbur sometimes clashed with the military establishment over how best to care for the refugees. For both women, helping the freedom-seekers was a battle that required standing up to the military government for their convictions but also subjected them to disrespect and contempt as they brought attention to what they perceived as unfair, and sometimes inhumane, practices and a lack of empathy. Some of the doctors treating the refugees also challenged officials they deemed incompetent, echoing the sentiments of the two aid workers.[xxii]

Previous historians have argued that the doctors’ and aid workers’ clashes with authorities sprang from “complex rivalries…fueled by ambition and personal animosity.”[xxiii] However, more recent interpretations of the historical record, including entries in Julia Wilbur’s diary and letters, as well as other sources, demonstrate the very real concerns that Wilbur and Jacobs had about care and treatment of the freedpeople and the difficulties they faced as women combating discrimination in the nineteenth century.[xxiv] Wilbur’s letters highlight the depths of her conflict with Gladwin, who considered her “out of her sphere” when military authorities asked her to accompany him to a meeting.[xxv] Notably, the disrespect experienced by the aid workers for voicing their concerns also becomes apparent in a document that deals with an official inquiry into Gladwin’s behavior in the fall of 1863, when Jacobs and Wilbur are called “busy bodies,” said to be “meddling in the affairs of Mr. Gladwin and endeavoring to sour the minds of the Negroes against their Superintendent.”[xxvi]

The disagreements resulted in Gladwin attempting to evict the two women from their rooms in the southern half of the S. Washington Street house to the point of being chastised by the military governor for his attempts.[xxvii] In fact, perhaps Wilbur’s relationship with Gladwin contributed to her decision to move to Washington, D.C. in early 1865, although the definitive reason for her departure from Alexandria remains unknown. Shortly before the move, she learned that Gladwin had lost his position as Superintendent of Contrabands due to his policies and actions relating to the burial of soldiers in Freedmen’s Cemetery. Perhaps this seemed like a triumph of justice to Wilbur, as she recorded in her diary on January 15, 1865:

When we returned from the meeting, Dr. Pettijohn informed us that Capt. Ferree was really to supersede Gladwin & an order to that effect had been given by Sec. of War….Well, well.[xxviii]

Conflicts with Gladwin and other government officials had their roots in perceptions of what constituted proper and ethical treatment. Housing conditions deemed “comfortable” for the Contrabands by Reverend Gladwin caused distress to Wilbur and Jacobs.[xxix] In addition, Gladwin threatened to flog those whom he perceived as misbehaving, telling Wilbur, “if you…knew these people as well as I do, you would find there is no other way of getting around them.”[xxx] Disagreements also developed over the payment of rent for rooms in government barracks at a price Wilbur and Jacobs deemed unaffordable for many of the refugees, with Gladwin threatening to evict the inhabitants and send them South.[xxxi]

Throughout their time in Alexandria, Wilbur and Jacobs nevertheless continued to work fervently for the needs and rights of the freedmen. They achieved considerable success in fighting against some of the more egregious offenses put in place or suggested by authorities. They thwarted a proposal to care for orphans in a smallpox hospital where the children would have been exposed to the deadly disease, and they caused a cessation to the torturous practice of subjecting Black female prisoners to punishment in a shower bath, where they were stripped and forcefully sprayed with freezing water.[xxxii] The “self-sacrificing work” of the two friends did not go unrecognized in the public media of their own era, as they were mentioned by name in an article in the New York Evening Post.[xxxiii]

Post War: The Freedmen’s Bureau

[The Freedmen’s Bureau was] charged with the study and plans and execution of measures for easily guiding, and in every way judiciously and humanely aiding, the passage of our emancipated and yet to be emancipated blacks from the old condition of forced labor to their new state of voluntary industry.[xxxiv]

W.E.B. Du Bois, Atlantic Monthly, 1901

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Signed into law just one month before the end of hostilities, Congress created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, to help African American people transition from enslavement to freedom. Administrative concerns included issuing rations and medicines; helping freedpeople find housing and paid employment; reuniting and resettling free families; assisting in the establishment of schools, churches, and businesses; and dealing with lands confiscated from Confederate sympathizers.[xxxv]

In Alexandria, the activities of the Freedmen’s Bureau were essential to the city’s reconstruction. The bureau took on many responsibilities previously under the purview of the office of the Superintendent of Contrabands and created the position of Superintendent of Freedmen. It maintained its own population statistics for the city, citing:

[T}here were no less than (8,000) eight thousand freedpeople in this city, according to the census taken during the fall of 1865. Of these about (5,000) five thousand fled from their homes during the rebellion, and sought asylum here where they would be under the protection of the Army.[xxxvi]

With the end of the war, the economy fluctuated and many aid workers like Wilbur and Jacobs were no longer present. The situation remained unstable for many of the freedpeople who made the city their permanent home. Reverend James I. Ferree, the second regional assistant superintendent for the Freedmen’s Bureau in Alexandria and the former Superintendent of Contrabands who had replaced Gladwin after the latter’s removal from the position, dedicated himself to support of the freedmen, ensuring that they received “full compensation” for any services performed after the effective date of the Emancipation Proclamation.[xxxvii] Ferree observed that the freedmen were “kept living from hand to mouth because of the exorbitant rents they…[were] compelled to pay for the rooms and shanties” in which they lived, echoing the earlier concerns of Wilbur and Jacobs. To mitigate this situation, he requisitioned buildings constructed or occupied during the war for continued use as hospitals, housing, and schools.[xxxviii] In addition, management of Freedmen’s Cemetery fell to the bureau in July 1865. The administrators continued to list names of the deceased and other information in the Book of Records that had been started under the supervision of Reverend Gladwin.[xxxix]

Source: Find A Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com), memorial page for J.I. Ferree, Find A Grave Memorial no. 70163040, citing Veterans Memorial Grove Cemetery, Yountville, Napa County, California; Maintained by Connie (contributor 47390019); and The Fare Facs Gazette, The Newsletter of Historic Fairfax City, Inc. (VA), Volume 13, Issue 4, Fall 2016

Footnotes

[i] Julia A. Wilbur to Mrs. Amy Kirby Post, 5 November 1862, Family papers of Isaac and Amy Kirby Post, 1817-1918, Rush Rhees Library, The University of Rochester, New York.

[ii] Cited in Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York, NY: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), 158.

[iii] Alexandria Gazette, 31 October 1862; “Monthly Record of Clothing Furnished Contrabands and Deductions from Their Pay therefor [sic], 1862-1863,” Office of Chief of Engineers, Record Group 77, Entry 571, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[iv] Henry L. Swint, editor, Dear Ones at Home (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 1966), 19.

[v] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 116-117.

[vi] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 117-118.

[vii] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va., Library of Virginia, Richmond, Accession Number 1100408, 2.

[viii] Tim Dennée and Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 20-21, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf; cited in Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 130.

[ix] Albert Gladwin, Twentieth Annual Report, American Baptist Free Mission Society, 1863, 9.

[x] Report to the Executive Committee of New England Yearly Meeting of Friends, Upon the Condition and Needs of the Freed people of Color in Washington and Virginia, Fortress Monroe, VA, November 10, 1864, 589.

[xi] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 82.

[xii] Cited in Ira Berlin, Steven F. Miller, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, editors, Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867, Series I, Volume II, The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Upper South (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 275.

[xiii] Harriet Jacobs was the first woman to author a fugitive slave narrative in the United States, although she was not widely celebrated until the archival work of Jean Fagan Yellin brought Jacobs’s work to life in the late 1980s.

[xiv] Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York, NY: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), 158.

[xv] Cited in Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York, NY: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), 164.

[xvi] Tim Dennée and Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf.

[xvii] Cited in Jean Fagan Yellin, editor, The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, Volume 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 401.

[xviii] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 109.

[xix] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 116-117.

[xx] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017),110.

[xxi] Dorothy Sterling, editor, We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997), 247-248; Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 155.

[xxii] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017); Charges filed by the Committee of the National Freedmen’s Association of Washington, “An Official Inquiry into the Conduct of The Reverend Albert Gladwin, Superintendent of Contraband at Alexandria, Virginia;” October, 1863, archived in Office of the Adjutant General Colored Troops Division 1863, Record Group 94, G26-83, Box 15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., compiled by T. Michael Miller, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, 2004.

[xxiii] Ira Berlin, Steven F. Miller, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, editors, Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867, Series I, Volume II, The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Upper South (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 251.

[xxiv] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017).

[xxv] Cited in Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 112.

[xxvi] Cited in Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 147.

[xxvii] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, , 2017), 149-150.

[xxviii] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 15 January 1865, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf.

[xxix] Cited in Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 121.

[xxx] Cited in Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 121.

[xxxi] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 121.

[xxxii] Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017),114, 127.

[xxxiii] Ulysses Ward, “The Freedmen of Alexandria. Their Improved Condition and Character, “New York Evening Post, May 2, 1865, cited in Paula Tarnapol Whitacre, A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time, Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose (University of Nebraska Press: Potomac Books, 2017), 132.

[xxxiv] W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” Atlantic Monthly, vol. 87 (March 1901), 354-365.

[xxxv] Records of the Field Offices of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, July 1865-July 1867, vol. 1 and 2, Record Group 105, Entry 3847, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxvi] Samuel P. Lee to Lieutenant Colonel William W. Rogers, 30 October 1866, Report of the working of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands from January 1, 1866 to October 31, 1866 inclusive, Record Group 105, Entry 3878, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxvii] Reverend James I. Ferree, Correspondence, Records of the Field Offices of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, July 1865-July 1867, vol. 1 and 2, Record Group 105, Entry 3847, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxviii] Reverend James I. Ferree to Major General O.O. Howard, 18 August 1865 and18 September 1865, Records of the Field Offices of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, Letters Sent July 1865-July 1867, Record Group 105, Entry 3847, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxix] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va., Library of Virginia, Richmond, Accession Number 1100408, 80-119; Timothy Dennee, Personal Communications, emails with Francine Bromberg, Nov. 27 – Dec. 5, 2019, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.