Community: African American Life in Early Alexandria

Community: African Americans Life in Early Alexandria

A city slave is almost a freeman, compared with a slave on the plantation. He is much better fed and clothed, and enjoys privileges altogether unknown to the slave on the plantation.[i]

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, 1845

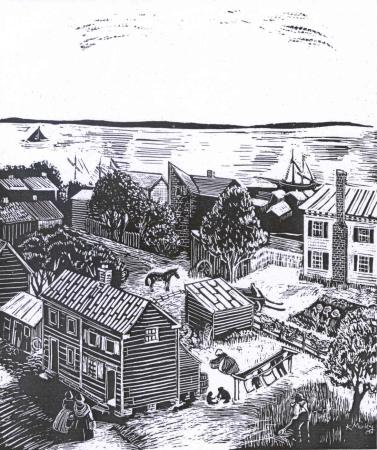

Caption. A conjectural drawing of the 400 block of South Royal Street in the 1830’s. The drawing is based on archaeological excavations in the Hayti neighborhood. The homes and shed in the foreground belonged to free African Americans. The homes in The Bottoms would have been similar to the ones in the drawing.

Source: Drawing by Karen Murley, Alexandria Archaeology, Alexandria, VA

When the freedom-seekers arrived in Alexandria, they found an established African American community in what had grown into a thriving port city. The first United States Census in 1790 identified 2,748 individuals in Alexandria, including 595 African American residents representing nearly 22% of the population; this number included 543 enslaved individuals and 52 Black people listed as free. A decade later, Alexandria’s Black population had reached 1,244, with 29% free. The free populace increased steadily, ultimately surpassing those enslaved by 1830. In 1840, the free Black population peaked at 1,627 as the number of enslaved individuals began to notably decline, having crested at 1,488 in 1810. Although a rising free Black population and a decreasing enslaved populace were statistically typical for most urban settings nationwide, Alexandria was the only locality in Virginia to have more free Black than enslaved people by 1850.[ii]

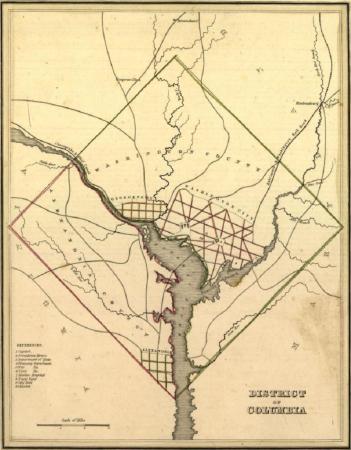

A partial explanation for these statistics relates to Alexandria’s inclusion as part of the nation’s new capital, which unofficially took place in 1790, became law under the Organic Act of 1801, and lasted until retrocession back to Virginia in 1847.[iii] The city’s status as a part of the District of Columbia undoubtedly offered more opportunities than most other Southern cities. The District’s less restrictive laws against assembly of and education for Black people encouraged free African American settlement. The prosperous seaport of Alexandria, with its urban lifestyle, provided anonymity and an added measure of liberty, with more opportunities for new experiences and personal accomplishments, encouraged by social, communal, religious, and educational networks.

Nevertheless, restrictive policies certainly still affected Alexandria’s African American residents, both free and enslaved. The Alexandria Council enacted laws limiting the freedoms of the Black population, perhaps bent on reducing the attraction of the city to free African American immigrants. For instance, one statute passed in 1799 stipulated “that in the future all black people found in the streets at night after the blowing of the horn, and having no passes from their masters, would be confined to jail.”[iv] Moreover, the city’s Black populace had to endure the knowledge that companies operating within the jurisdiction engaged in human trafficking with the sale of enslaved individuals to plantations in the South.[v]

By the middle of the nineteenth century, retrocession from D.C. back to Virginia placed additional constraints on opportunities for the city’s African American population, and many free Black individuals left for more unrestrictive polities to the north. Just a few years after retrocession, Congressional passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, may have contributed to an increase in the number of enslaved people embracing and seeking self-emancipation through attempts to escape to Canada - despite, or perhaps because of, the law’s harsh conditions. The Act required all citizens to assist in the return of those fleeing enslavement to their enslavers and added to the terrorizing policies facing those with the courage to self-emancipate. Nevertheless, some enslaved people made the decision to leave Alexandria or passed through the city on their way north to freedom.

Source: LOC ct00053, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C.

Neighborhoods, Schools and Churches

[P]erhaps the earliest [African American school in Alexandria] was the one taught by Mrs. Cameron, a white Virginia lady, who had for some years a primary school…on the corner of Duke and Fairfax streets…[vi]

U.S. Department of Education, 1871

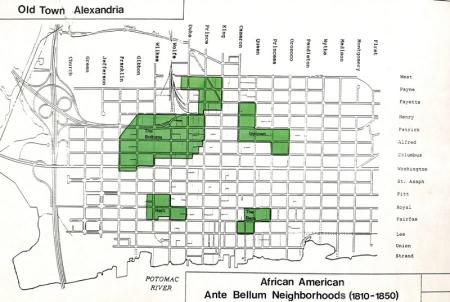

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Alexandria, VA

The establishment of Alexandria’s free Black neighborhoods began as early as the 1790s.[vii] Families settled in a low-lying area in the southwestern section of town that became known as the Bottoms and farther east in an area called Hayti. Pronounced “Hay-Tie,” the latter neighborhood bore the name of the Caribbean nation founded after the successful 1791 uprising that resulted in freedom for the island’s enslaved population. In the early nineteenth century, free Black settlement also took hold in what became known as Uptown in the northwestern part of the city. Fishtown, along the northern waterfront, bustled seasonally during the annual fish runs. In these burgeoning neighborhoods, some enslaved people shared homes with other African American individuals living free.[viii]

Churches and schools for African American people sprang up in the growing neighborhoods. Alexandria’s Black churches became spiritual, social, and charitable centers with the founding of the Alfred Street Baptist Church in 1806 and Roberts Memorial United Methodist Church (originally Davis Chapel Church) in 1832.[ix] By about 1809, Alexandrians had established schools for African American children,[x] capitalizing on the educational possibilities offered through inclusion in the District of Columbia.

Work Opportunities

Amos Beckly, 24, brickmaker; Richard Bumry, 30, stevedore; James Carter, 42, baker; Richard Digs, 25, cooper; Samuel Dundass, 38, carpenter; John Nickins, 50, clerk; Eliza Syphax, 24, servant[xi]

Alexandria County Register of Free Negroes, 1858

The urban setting also provided openings for both free and enslaved Black people to learn skills and apply business acumen. They worked alongside white men, filling a myriad of positions, especially in Alexandria’s fisheries and building trades. The various jobs worked by the city’s self-employed free Black men recorded in the 1858 Alexandria County Register of Free Negroes included brickmakers, porters, clerks, whitewashers, cartmen, wire workers, bakers, wood sawyers, blacksmiths, carpenters, plasterers, cordwainers (shoemakers), caulkers (boat sealers), coopers (barrel makers), riggers for ships, shipyard laborers, stevedores (dockworkers), fishermen, and oystermen. Free Black individuals also served as servants, cooks, barbers, hucksters (peddlers), teamsters, and domestic help in hotels, restaurants, and the city’s many boarding houses.[xii] Like the free Black population, many of the people enslaved in urban settings like Alexandria were trained in a variety of skills benefiting enslavers, thus creating a notable populace of enslaved artisans.[xiii] Enslaved individuals were also hired out, some earning wages and buying freedom for themselves and family members.

Restrictions, Human Trafficking, and Retrocession

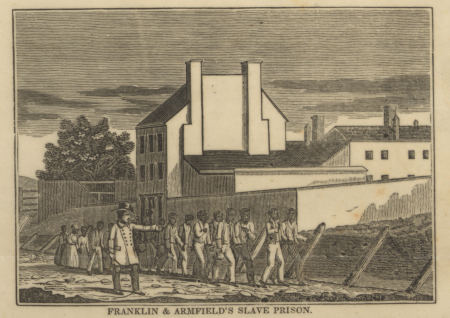

Bill Keeling, male, age 11, height 4’5” | Elisabeth, female, age 10, height 4’1” | Monroe, male, age 12, height 4’7” | Lovey, female, age 10, height 3’10” | Robert, male, age 12, height 4’4” | Mary Fitchett, female, age 11, height 4’11”[xiv]

Enslaved children sold South by the Franklin and Armfield Office

Source: American Anti-Slavery Society, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Despite the relative advantages of urban life, laws and restrictive policies had a profound effect on the lives of Alexandria’s African American people even throughout the period of inclusion in the District of Columbia. Statutes passed in the 1790s and the first decade of the nineteenth century put in place night-time curfews, required registration of free Black individuals, and set limitations on free Black immigration into the city.[xv]

In 1807, Congress voted to ban the importation of slaves into the United States, effective January 1, 1808. The ban discouraged manumissions by raising the value of enslaved people, and the domestic slave trade flourished. Many enslavers in northern Virginia seized the opportunity to sell to the southern slave market. Franklin & Armfield, one of the largest and most lucrative and notorious slave-trading firms in America, established their business on Duke Street in Alexandria in 1828. By the time of the Civil War, Franklin and Armfield no longer operated in the city. However, their building remained in use by subsequent traffickers in human suffering, including Price, Birch & Company, purchaser of the property in 1858 and 1859. Another notorious trafficker, Joseph Bruin, operated his business four blocks to the west. Alexandria slave dealers made fortunes by splitting apart families for profits, selling women into prostitution, and sending enslaved laborers to the Deep South’s brutal cotton and sugar plantations.[xvi]

Retrocession of Alexandria from D.C. back to Virginia in 1847 heralded an era of greater restrictions, subjecting Alexandria’s free African American residents to the strictly enforced racial laws of the Commonwealth. Many Virginia laws had gone into effect as a result of white fears after the Nat Turner Rebellion in 1831. People of African descent were prohibited from preaching the Bible, testifying in court, possessing firearms, conducting gatherings or meetings, and traveling without restrictions. Virginia state law also forbade the education of African American people, forcing closure of the few African American schools in the city. The number of free Black individuals in Alexandria notably declined as many migrated north in search of the freedoms they had previously experienced as residents of the District of Columbia. Still, on the eve of the Civil War, the percentage of free Black people in Alexandria was markedly greater than in any other urban area in the Commonwealth, except for Richmond. Although it had continued to decline, the enslaved population of Alexandria was still the fifth highest of Virginia’s major towns and cities with 1,386 Black people held by 251 enslavers. [xvii]

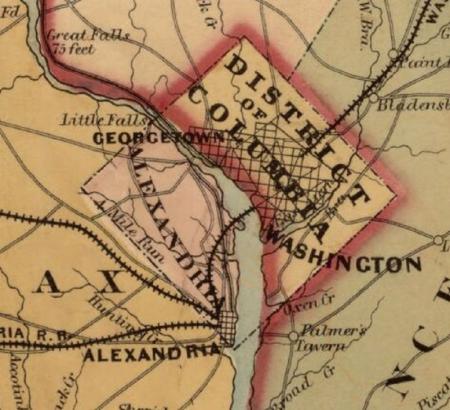

Portion of 1861 war map of Baltimore, Washington and vicinities showing boundary separating the District of Columbia and Alexandria, Virginia, based on survey by G.M. Hopkins, Jr., and published by Jacob Weiss of Philadelphia.

Source: Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C.

The Fugitive Slave Act and the Underground Railroad

Source: National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Shortly after retrocession, Congress enacted the Compromise of 1850, which included the Fugitive Slave Act.[xviii] One of the most controversial laws ever passed, the act was intended as a temporary solution to keep the states united. It required that all citizens assist in the recovery of those who had sought self-emancipation, denied enslaved people the right to a jury trial, and made the process of filing a claim easier for enslavers. Activist and author Harriet Jacobs, formerly enslaved, stated that she considered the passage of the law to be “the beginning of a reign of terror to the colored population.”[xix]

Despite the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, many enslaved people continued to take the significant risks associated with self-emancipation. Most freedom-seekers undoubtedly planned their escapes without assistance, running northward independently to minimize the risk of being caught. However, the Underground Railroad, an anti-slavery network of both white and free Black people, helped many to flee during the first half of the nineteenth century. The “compromise,” through its harshness and severity, may have precipitated a surge of activity along the network’s numerous routes toward and into Canada in the decade before the start of the Civil War.[xx] An 1859 article from the Alexandria Gazette recounts Alexandria’s role in this passage to freedom along the Underground Railroad:

On Saturday evening last, not less than fifteen thousand dollars worth of “property” passed through this city [Rochester, NY] on a train of the “Underground,” fairly rivaling the Central. But the most wonderful part of the story is that in the transit across the Suspension Bridge at Niagara, the “property” suddenly became metamorphosed into about a dozen smart, intelligent, young and middle-aged men and women. These “chattels personal” were part of a large shipment which left Alexandria, Va., about the time of the Harper’s Ferry insurrection.[xxi]

"Twenty-eight Fugitives Escaping from the Eastern Shore of Maryland,” October 28, 1857; engraving by John Osler published in William Still’s book The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia: Porter & Coats, 1872).

Source: House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College; prepared for digital use by John Osborne, Dickinson College, June 28, 2008. http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/18721.

Footnotes

[i] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (Boston, MA: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), 34.

[ii] Belinda Blomberg, Free Black Adaptive Responses to the Antebellum Urban Environment: Neighborhood Formation and Socio-economic Stratification in Alexandria, Virginia, 1790-1850. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, American University, 1988. University Microfilms, Intl., Ann Arbor, Michigan; Mark K Walker, Madeleine Pappas, Jesse Daughterty, Christopher Martin and Elizabeth Crowell, Archaeological Evaluation of the Alfred Street Baptist Church (44AX161), Alexandria, Virginia, prepared by Engineering Sciences, Washington D.C. for FAIA & Associates, PC, Oxon Hill Maryland and the Alfred Street Baptist Church, Alexandria, VA, 1992, 6, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[iii]An Act for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the Government of the United States, 1st Congress, 2nd Sess, ch.28, enacted July 16, 1790; An Act to amend “An Act for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the Government of the United States,” 1st Congress, 3rd Sess, ch.17, enacted March 3, 1791; An Act Concerning the District of Columbia, 6th Congress, 2nd Sess., ch. 15, 2 Stat. 103, enacted 27 February 1801.

[iv] T. Michael Miller, Research Historian, Office of Historic Alexandria, Memorandum to Jean Federico, Director, Office of Historic Alexandria, 13 May 2004, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[v] Benjamin A. Skolnik, Building and Property History, 1315 Duke Street, Alexandria, Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, Virginia, January 2021, media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/archaeology/1315dukestbuildinghistoryskolnik2021.pdf

[vi] U.S. Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), 283.

[vii] Pamela J. Cressey, The Nineteenth Century Transformation and Spatial Development of Alexandria, Virginia, Alexandria Archaeology, publication no. 1, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA., paper presented at the First Joint Archaeological Conference, January 5-9, 1989, Baltimore, MD, 1988.

[viii] David R. Goldfield, “Black Life in Old South Cities,” in Edward D.C. Campbell, Jr., Before Freedom Came, African American Life in the Antebellum South (Richmond, VA: The Museum of the Confederacy, 1991), 137.

[ix] The Afro-American Institute for Historic Preservation and Community Development, “A Study of Historic Sites in the Metropolitan Washington Region of Northern Virginia and Southern Maryland Importantly related to the History of Afro-Americans: Beulah Baptist Church,” Washington, D.C., August 1978, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[x] U.S. Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), 187, 283.

[xi] Alexandria (Arlington) County Register of Free Negroes, 1858, archived with local government records collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia, courtesy of Wesley E. Pippenger, transcribed by Tim Dennee, freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/1858register.shtml

[xii] Alexandria (Arlington) County Register of Free Negroes, 1858, archived with local government records collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia, courtesy of Wesley E. Pippenger, transcribed by Tim Dennee, freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/1858register.shtml; Dorothy Provine, Alexandria County, Virginia, Free Negro Registers, 1797-1861 (Berwyn Heights, MD: Heritage Books, 1991), cited in Harold W. Hurst, Alexandria on the Potomac: The Portrait of an Antebellum Community (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1991), 37.

[xiii] Ann Deines, “The Slave Populations in 1810 Alexandria, VA, A Preservation Plan for Historic Resources,” Master’s Thesis, George Washington University, Washington, D.C., 1994, 8-13.

[xiv] Franklin and Armfield Office, National Park Service, nps.gov/places/franklin-and-armfield-office.htm

[xv] T. Michael Miller, Research Historian, Office of Historic Alexandria, Memorandum to Jean Federico, Director, Office of Historic Alexandria, 13 May 2004, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xvi] Lisa Krauss, John Bedell and Charles LeeDecker, Archaeology of the Bruin Slave Jail (Site 44AX0172), prepared by The Louis Berger Group, Inc., Washington, D.C., 2010, 47, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/archaeology/sitereportkraus2010bruinslavejailax172.pdf; Benjamin A. Skolnik, Building and Property History, 1315 Duke Street, Alexandria, Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, Virginia, January 2021, media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/archaeology/1315dukestbuildinghistoryskolnik2021.pdf; Janice G. Artemel, Elizabeth A. Crowell, and Jeff Parker, The Alexandria Slave Pen: The Archaeology of Urban Captivity. Engineering-Science, Inc., Washington, D.C., media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/archaeology/sitereportartemel1987slavepenax75.pdf.

[xvii] U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics of Virginia, Slaveholders and Slaves, Records of U.S. Census Bureau, 1860, M653, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xviii] An Act to amend, and supplementary to, the Act entitled "An Act respecting Fugitives from Justice, and Persons escaping from the Service of their Masters,” approved February twelfth, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-three, 31st Congress, 1st Session, ch.60, 1850, U.S. Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America, vol. 12 (Boston, MA: Little Brown and Company, 1851), 462-465.

[xix] Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (unabridged) (New York: Dover Publications, 2001), 155.

[xx] Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad, National Historical Park, Maryland, History and Culture, National Park Service, nps.gov/hatu/learn/historyculture/index.htm.

[xxi] “The Underground Railroad,” Alexandria Gazette, 29 October 1859.