Community: Putting Down Roots in a City Under Siege

Community: Putting Down Roots in a City Under Siege

[W]e have had eight to ten thousand … refugees from Virginia slavery [in Alexandria]; about two thousand … have enlisted into the army..., and nearly as many more have been employed in the Commissary and Quartermaster’s service, and in the hospitals…. They have, within three years, built over a thousand dwelling houses…They have built three churches…together with two…wooden school houses…. They have now twenty teachers employed in the education of their children…. [i]

Unionist Judge John C. Underwood, Letter to William Syphax, July 12, 1865

Beginning as the Old Shiloh Society gathered in the nearby L’Ouverture Hospital mess hall, 50 former enslaved people established a congregation. The first edifice of Shiloh Baptist Church was erected on West Street near Duke Street. and dedicated on September 26, 1865.

Source: Google Maps image (enhanced)

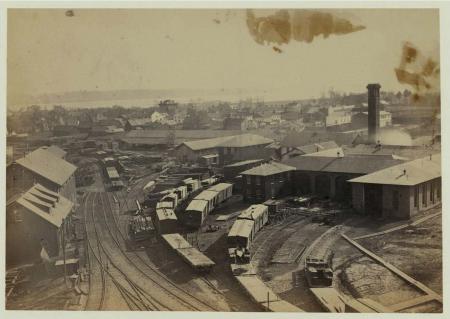

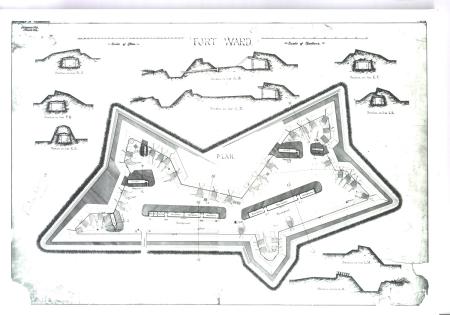

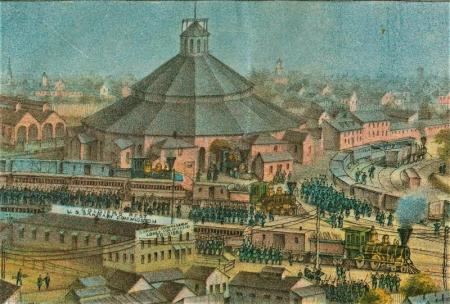

On May 24, 1861, just hours after Virginians had voted to secede from the Union, federal troops invaded Alexandria. The city would remain under martial law throughout the entirety of the war. With the port and a network of rail lines, the defensive value of Alexandria, just across the Potomac and downriver from Washington, could not be overestimated. Alexandria served as a staging area and supply center for Union activities with public buildings and private homes converted into offices, military headquarters, hospitals, and prisons. New construction, under the jurisdiction of the Quartermaster’s Department, added the infrastructure to support Union activities and needs. The U.S. Military Railroad Construction Corps was based in Alexandria, where separate routes leading to the north, northwest, and south already existed to bring troops and supplies to the battlefields and injured soldiers back for treatment. The federal government completely controlled the city’s port on the Potomac River. In addition, the military immediately established a circle of more than 160 fortifications intended to shield the nation’s capital from invasion. Remnants of the Defenses of Washington constructed within the present-day limits of Alexandria remain visible today, notably Fort Ellsworth on the grounds of what is now the George Washington Masonic National Memorial, and Fort Ward, well-preserved and interpreted in what is currently a historic park in the western part of the city.

The immediate influx of more than 2,100 soldiers[ii] caused great tension and mayhem for Alexandrians, with more than one-half of the residents fleeing to Confederate territory and business activity decreasing “by at least eighty or ninety per cent.”[iii] Residents who remained in the city confronted not only a constant military presence, but government employees, camp followers, opportunists, and entrepreneurs who sought to benefit from the war.[iv] Civilian travel was restricted, passes were required for traveling to Washington, farm goods were confiscated, and those suspected of being disloyal to the Union were often arrested and placed in jail.[v]

Thousands of freedom-seekers, arriving destitute and in need of food and shelter, added to the changing demographics. The U.S. military recognized the increased potential for a humanitarian crisis as overcrowding and poverty created conditions especially conducive to the spread of dangerous communicable diseases, such as smallpox and typhoid fever. In addition, these highly contagious diseases posed a significant threat to the troops and to the logistical needs of the Union forces.[vi]

In October 1862, Alexandria’s new military governor, Brigadier General John P. Slough, took several administrative actions to address the complex issues that arose as the self-emancipating refugees continued to pour into the city. The need for labor to support the war effort provided a little relief to the critical situation. Slough appointed the first commissary to the Contrabands, Sidney A. Burdge, who managed their employment and rations, and the first physician, Dr. Charles Culverwell, who oversaw medical treatment as well as attempts to vaccinate the population against smallpox.[vii] At about the same time, Reverend Albert S. Gladwin, a white Baptist organizer born in Connecticut, began performing the duties of Superintendent of Contrabands, a position that focused on helping to manage and administer to the increasing number of freedom-seekers within the city.[viii]

A new and different city began to take shape under military control. Despite the housing crisis and difficult living conditions, new neighborhoods arose as the freedmen constructed shelters on undeveloped land in the city and also resided in barracks built by the government. Recognized for their ability to contribute to the Union war effort, the freedom-seekers found jobs in Alexandria. Many of the men served as laborers for the U.S government, and women often worked in more domestic capacities. The new arrivals established churches and sought educational opportunities, putting down roots and building up community.

Source: Alexandria Black History Museum

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (Part of Mathew Brady Civil War Photograph Collection)

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Source: Fort Ward Quartermaster Map, Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Source: The Library Company of Philadelphia Print Dept.

Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

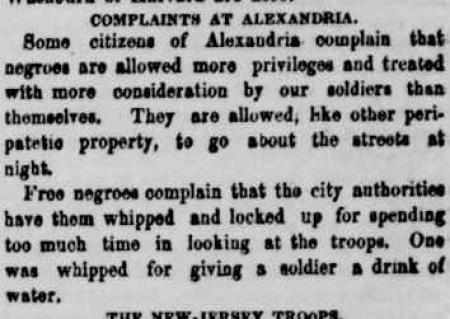

A Federal Protection Zone for an Army of Refugees

Source: New York Daily Tribune, vol. XXI, no. 6274, 31 May 1861, page 4

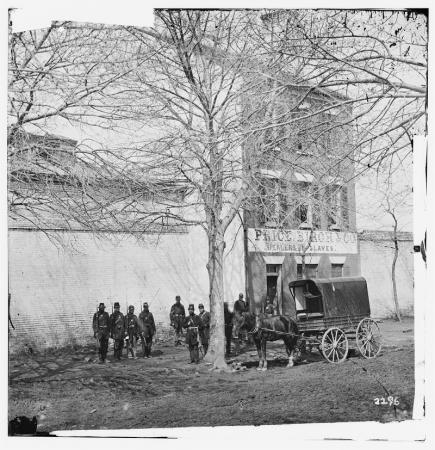

While ill-treatment and prejudice against African American people still surfaced on the streets of Alexandria,[ix] the Union control essentially created a federal protection zone for its Black residents, and ultimately a much sought-after destination for those seeking freedom, despite its restricted military form. One of the first actions taken by the Union on May 24, the very day the Army entered the city, was liberation of enslaved African American individuals held for sale in the Price, Birch & Company slave pen. Shortly thereafter, the Union Army claimed the building for use as a military jail, primarily for imprisonment of Union soldiers who committed disciplinary infractions.[x]

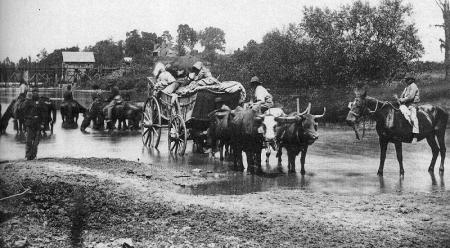

May 24 was also the date of General Butler’s declaration that formerly enslaved people were “contraband of war,” bringing the promise of a new beginning for those who had been deprived of their liberty. With the subsequent passage of the Confiscation Acts in 1861 and 1862, what might be characterized as an army of refugees, sometimes as many as 100 a day,[xi] poured into Alexandria, mostly from the nearby war-torn Virginia counties of Fairfax, Fauquier, Loudon, Prince William and Culpeper. They steadily increased in number throughout the war, although an exact count of those arriving and remaining in Alexandria is not easily discernible due to inaccurate records and tabulations.

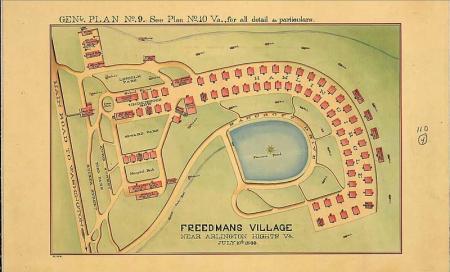

According to a report by the Freedmen’s Relief Society, Alexandria was home to 3,000 freedom-seekers in 1863; this number would increase to more than 7,000 by September 1864.[xii] Estimates of freedpeople in Alexandria City from 1863 to 1865 ultimately reached 8,000 to 10,000.[xiii] Another 1,000 lived north of the city in Freedmen’s Village on the grounds of Arlington House, the confiscated estate of Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his wife Mary Custis Lee in what was then considered Alexandria County (renamed Arlington County in 1920).[xiv] Significant numbers had also fled to the Fairfax Seminary and Fort Ward area, likewise under federal control in what is currently the western part of the city.[xv] Perhaps the largest number of those determined to free themselves during the war sought refuge in Washington, D.C., just across the Potomac River from Alexandria. By 1865, as many as 40,000 formerly enslaved individuals had made their way to the capital city.[xvi]

Source: Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Lives and Work

…[I]f there ever should be recognition of their great services, the faithful contrabands will be justly entitled to their share; no other class of men would have exhibited so much patience and endurance under days and nights of continued and sleepless labor.[xvii]

General Herman Haupt, Commander of the U.S. Military Railroad in Alexandria, Reminiscences, 1901

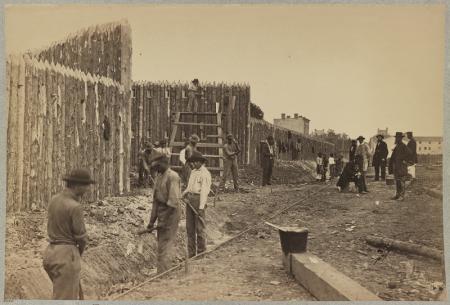

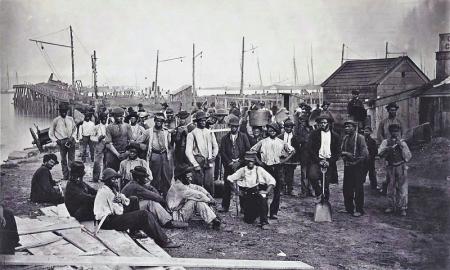

Contrabands employed in the construction of stockades for defensive purposes around the U.S. Military Railroad complex, 1861.

Source: National Archives, Washington, D.C. 111-B-523. National Archives Identifier 524934

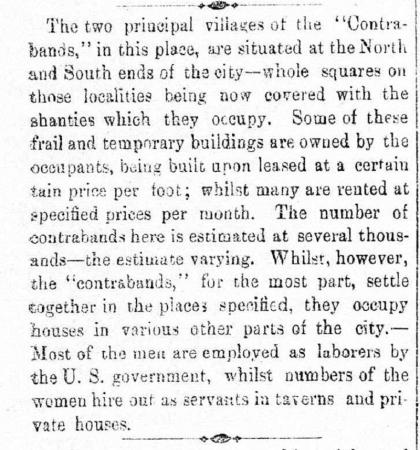

Despite their difficult journeys, freedom-seekers entered Alexandria ready to contribute to the Union war effort and to lend their industriousness to bolster the economy of the city. The Local News noted, “Most of the men are employed as laborers by the U.S. government, whilst numbers of the women hire out as servants in taverns and private houses.”[xviii] Their jobs ranged from nurses and hospital stewards to stevedores (dock laborers) and road workers, from painters and carpenters to laundresses and cooks, often utilizing the skills they had mastered in their enslavement.

African American Labor: Necessary and Valued

The intense need for “Contraband” labor by the Union Army in Alexandria and the D.C. area reveals itself in the records and correspondence kept by the soldiers stationed there. Officers of the Quartermaster Department, responsible for supplying goods and services to federal troops, often complained that there were not “sufficient number[s] of ‘Contrabands’ here…” to accomplish the necessary work and that those who were in the town already had jobs as laborers.[xix] To meet the need for workers, the government transported groups to the vicinity of D.C. In October 1862, Major General John Adams Dix of Fortress Monroe, the Union-held fortification where a burgeoning population of African American refugees were seeking asylum, sent 195 individuals by steamer “for work on the fortifications of Washington….”[xx] This is one of the first instances of freedom-seekers being relocated to work for the Union Army. Those initially sent included a number of women and children, who, although not essential to the military labor force, were members of intact families the government respectfully insisted on keeping together.[xxi] As needs intensified, nearly 250 more arrived in Alexandria and Washington a few weeks later, again sent by steamers from the fort at Hampton Roads.[xxii] In the latter years of the war, freedmen are known to have worked on the expansion of the fortification at Fort Ward in what is now western Alexandria.[xxiii]

Letters of the Quartermaster Department and the Engineer of Defenses also document the value placed on the labor of the freedom-seekers, frequently employed to build and maintain the railroads, roads, rifle pits, and fortifications surrounding Washington, D.C. One letter detailed the significant role that African American laborers played in the construction and maintenance of the roads around the Defenses of Washington:

[I]f we can obtain “contrabands” in sufficient numbers, they will furnish the true solution of the subject. I would propose to get about 1000 negroes, to organize them into 3 gangs under a general superintendent….If such a force was now organized, I think the roads could be put in good order before Christmas, and if it was properly managed they could be kept in tolerable order during the entire winter and spring...[xxiv]

Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

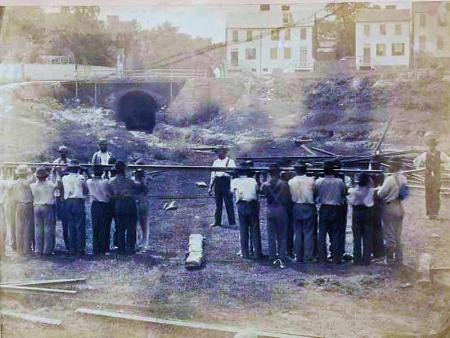

With Alexandria serving as a bustling staging ground for Union supplies and men, the military government similarly put many freedom-seekers to work on the docks and wharves of the port as well as on the railroad to keep the stream of soldiers and materiel flowing. African American men, working under General Herman Haupt, commander of the U.S. Military Railroad Construction Corps, laid the tracks and constructed the bridges, barges, and related fortifications. In fact, construction of the railroad complex south of Duke Street, between Alfred and Payne streets in Alexandria, fell almost entirely to African American laborers. In Haupt’s reminiscences, written decades later, he applauded the tireless work of the freedom-seekers:

With the exception of the superior officers and the foremen, the Construction Corps consisted almost entirely of so-called “contrabands.” Thousands of these refugees had flocked into Washington, and from them were selected several hundred, healthy, able-bodied men familiar with the use of the ax. These Africans worked with enthusiasm, and each gang with a laudable emulation to excel others in the progress made in a given time.[xxv]

Contraband laborers at the Quartermaster's Coal Wharf (at the foot of Montgomery Street) in Alexandria, Va. Photographed between 1863-1865 and attributed to photographer Andrew Russell.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Resilience in the Face of Injustice

While military officials affirmed the need to compensate African American laborers at the going rate for their work,[xxvi] freedmen received lower wages than white workers in comparable jobs.[xxvii] In addition, payment was frequently delayed or never granted. The wages they did receive often did not come close to covering expenses, as “prices rose as fast as wages,” and refugee laborers found that “‘every thing [sic] is so high’ their money would ‘not go any whare [sic]’.”[xxviii] In inquiring about payment of wages to the Black laborers, one Union official noted that “[m]any have been at work for more than two months and never received any pay, they are almost destitute of clothing and other necessaries.”[xxix] Despite these difficulties and injustices, the strength and determination of the freedom-seekers comes through in this description by Harriet Jacobs, who became an aid worker and educator in Alexandria:

They have had to struggle along and help themselves as they could. But though this has been discouraging, at times, it teaches them self reliance [sic]; and that is good for them, as it is for everybody….[T]hey are willing to earn their own ways, and generally capable of it.[xxx]

Contributions of Freedwomen

Likewise aiding the war effort, African American women sewed and laundered uniforms, cooked meals, or worked in nearby gardens to cultivate food for soldiers and fellow refugees. One such documented instance took place at Volusia, a plantation located a few miles west of the city limits at the time. The 5th New Hampshire Volunteers encamped from December 1861 until March 1862 on the grounds of Volusia, and their commander asked for his laundry to be done, “offering to ‘cheerfully pay almost any price’ for the service.”[xxxi] Black women were also caretakers of the home, which included looking after the elderly, children, and an ever-growing orphan population. Harriet Jacobs proudly said of the women, “I am bound to testify that I have never known them, in any one instance, refuse to shelter an orphan. In many cases, mothers who have five or six children of their own, without enough to feed and cover them, will readily receive these helpless little ones into their own poor hovels.”[xxxii]

Source: “Slaves at Volusia: Photographs of Felix Richards’ Slaves near Alexandria, Virginia,” by Amy Bertsch

Housing and Neighborhoods

Within the last eight months seven hundred little cabins have been built, containing from two to four rooms. The average cost was from one hundred to two hundred and fifty dollars…. When we went round visiting the homes of these people, we found much to commend them for. Many of them showed marks of industry, neatness and natural refinement...[xxxiii]

Harriet Jacobs, Aid Worker, Educator and Author, Letters from the Teachers of Freedmen, 1864

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Alexandria, VA

A housing crisis developed in Alexandria as freedom-seekers flooded into the Union-controlled city. John C. Wyman, the Provost Marshal of Alexandria, noted how ill-prepared the military government was for this influx of refugees in October of 1862:

Of course no intimation of their coming had been given and no property provision had been made for their accommodation and as they were arriving daily it was found impossible to furnish them with suitable quarters.[xxxiv]

The early solutions were haphazard at best and often resulted in substandard living conditions for those entering the city. At first, freedom-seekers crowded into abandoned buildings, including the homes of Confederate sympathizers who had fled the city. Some took up residency in available rooms of the old slave pens, like the Franklin and Armfield property that had been turned into the military jail. The living conditions in these abandoned structures were worse than sub-standard -- “so crowded that great danger exists of diseases which may prove contagious—and fatal.”[xxxv] A letter by Julia Wilbur brings to light the deplorable conditions she found in her first year as an aid worker in Alexandria:

In the old Slave pen there are several rooms. In the small room (a brick floor I discovered through the dirt) with one window were 20 women & children, many of them sick, a little fire wh[ich] they were huddled around, c[ould] not all get to it at once, & they were wrapped in their old rags. The weather has changed & they feel the cold very much now. They are furnished with a very little wood, & there are now many sick children that will die for the want of fire.[xxxvi]

Compelled by the continued arrival of so many freedom-seekers into Alexandria and the unrelenting perseverance of reformers and aid workers like Julia Wilbur and Harriet Jacobs, government officials eventually became convinced of the need for the construction of barracks specifically for the Contrabands.[xxxvii] In addition, communities sprang up on vacant land outside of the developed areas of the city.

Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Government Barracks

Construction of barracks for the freedom-seekers by the military government began in late 1862 in three areas of Alexandria—two sites near the railroad yard and one at the wharf bounded by Union, Wolfe, and Wilkes streets. One of the sites, which became known as the Prince Street Barracks, stood at the southeast corner of Payne and Prince streets on the city block immediately east of the military jail (the old slave pen property). Occupation of the Barracks, as they were often called, appears to have begun in late February 1863.[xxxviii] They became part of the L’Ouverture Hospital complex when the medical facility for the treatment of the city’s African Americans soldiers and civilians opened in February 1864 on the block containing the prison. The area emerged as the core of an African American community with the establishment of Shiloh Baptist Church, probably in the Barracks sometime in 1863, by a group of about 50 African American residents.[xxxix] Reverend Leland Warring, the first African American preacher of the church, is known to have resided in the Barracks and would go on to lead the Shiloh congregation until 1889.[xl] Shiloh’s 1893 historic building currently stands on the block just west of the former location of the hospital complex.[xli]

Despite the best efforts of the military, however, the new barracks remained overcrowded and unsanitary. By May 1863, reports indicated the “quarters set apart for the use of Contrabands [are] all filled.”[xlii] With numbers continuing to increase, some of the freedpeople were transferred to housing north of the city at Freedmen’s Village, officially established in December 1863.[xliii]

Although the federal government partially funded relief efforts for the freedom-seekers with a tax on wages, rent was still collected from those who lived in the government facilities. Activists like Julia Wilbur protested the policy, claiming amounts were too high and left little for other needs, but most of the refugees were charged about $5 per month for government housing.[xliv]

Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

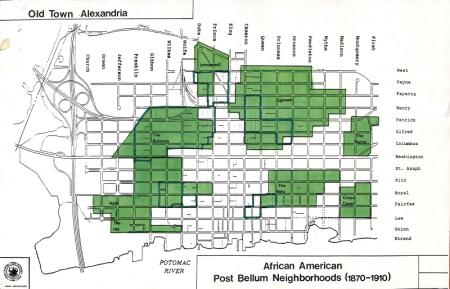

New Neighborhood Development

In addition to the government barracks, refugee communities sprang up on vacant land, particularly on the northern and southern outskirts of the developed part of the city as the existing free Black neighborhoods began to extend beyond their antebellum borders. More than a dozen new communities took shape on undeveloped city blocks, “whole squares on those localities being…covered with…shanties.”[xlv] The communities grew quickly, with the “frail and temporary buildings” either rented outright or perhaps more often built by the freedmen and subject to ground rent.[xlvi] Activist and aid worker Harriet Jacobs reported that the land was leased for $1.00 per month for a 15 x 20-foot lot.[xlvii]

Community names often reflected the areas the refugees had left, characteristics of their new settlements, or recognition of those who supported the cause of freedom. One 1864 reporter recounted, “We have ‘Petersburg,’ and ‘Richmond,’ ‘Contraband Valley,’ and ‘Pump Town,’ and twenty other towns in our midst.”[xlviii] The name Petersburg for a settlement on the northern outskirts of town undoubtedly hearkened back to the area in Virginia that many of the refugees had fled, notably a location of intense fighting during the war. In later years, Petersburg absorbed Grantville, a neighboring community likely established at approximately the same time and named to honor its founder, shoemaker Peter Grant, credited with building the first house in the neighborhood for a cost of $39.[xlix] A post-war account attributes the name in part to General Grant, noting that the recognition of both General Grant and Peter Grant was said to have “killed two birds with one stone.”[l] Sumnerville, an Alexandria neighborhood mentioned by Harriet Jacobs, took its name from the Hon. Chas. Sumner, described by Jacobs as a man of “large heart and great mind… nearly murdered…for standing up so manfully in defence [sic] of Freedom;”[li] Other communities included the Hill, Vinegar Hill, and Newtown, names found in the records of the Superintendent of Contrabands.[lii] Some locations and boundaries of the emerging neighborhoods may never be known definitively, as locations were absorbed into post-war Black neighborhoods that grew from the core areas. However, at least one, the Berg, shortened from Petersburg, retained its wartime identity.

Source: “Local News,” Alexandria Gazette, 10 January 1865

Improvement Despite Overcrowding

Overcrowding, with so many concomitant problems, such as the spread of disease, limited access to clean water, improper sewage disposal, and lack of sufficient food, plagued those living in these new neighborhoods, just as it had in the housing alternatives provided by the military government. In November 1863, Julia Wilbur recounted the challenge of visiting all of the homes of the burgeoning communities, stating ”Grantville is so large that I have given up the idea of visiting it all.”[liii] An 1864 newspaper article paints a picture of the crowded conditions of life in these neighborhoods:

These houses, huddled together, with no conveniences for drainage, swarm with a mass of men, women, and children. We have no means of knowing what are their numbers…Those of our citizens who lived here before the war, would hardly know the place, if they could return here, so overgrown by the negro shanties have been the commons and vacant lots….It is said that the inhabitants of these new and strange villages are generally orderly and give no occasion for the interference of the civil or military police.[liv]

Nevertheless, with the aid of reformers like Julia Wilbur and Harriet Jacobs and the provisions of the military government, gradually the conditions improved. Reverend Samuel May, Jr., an activist who wrote regularly for the National Anti-Slavery Standard, documented not only the conditions in the Contraband homes, but also the determination and self-sufficiency of the occupants:

Grantville…is composed of small and humble dwellings, yet their own, very many (I believe the most) of them built and paid for out of the proceeds of their own labor. We entered many of these humble abodes, being always received with civility and propriety, and finding neatness, and an ambition to make the best appearance possible with their few possessions, the prevailing rule...[lv]

Schools and Churches

In Alexandria, and in various other places,… one of the first acts of the negroes, when they found themselves free, was to establish schools at their own expense; and in every instance where schools and churches have been provided for them, they have shown lively gratitude and the greatest eagerness to avail themselves of such opportunities of improvement.[lii]

American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, 22 June 1864

Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Denied education as enslaved individuals, freedmen were eager to learn. William Davis, an early freedom-seeker at Fort Monroe in Hampton Roads, posited:

Some say we have not the same faculties and feelings with white folks. All we want is cultivation. What would the best soil produce without cultivation? We want to get wisdom. That is all we need. Let us get that, and we are made for time and eternity. [lvii]

By the end of the war, dozens of schools had been built in Alexandria to “cultivate” the minds of the thousands of students who flooded the city.

Alexandria’s freedpeople placed a high value on education, initially establishing schools “wholly by themselves.”[lviii] Mary Chase, formerly enslaved, opened what may have been the first known school for freedom-seekers in the United States near Wolfe Street in Alexandria on September 1, 1861. Abandoned by her enslaver when the military occupied the city, Chase had experienced the educational freedoms, albeit limited, allowed African American people prior to retrocession of Alexandria to Virginia. She seized the opportunity offered by federal control to “courageously set to work for the good of her race.” Her pioneering educational facility was the first of twenty-four schools for African American students established in Alexandria during the Civil War. By the end of 1862, four additional schools had been “started and conducted by colored persons” now able to assume responsibility for their own education as well as that of other Black individuals.[lix]

Source: Hampton History Museum and EncyclopediaVirginia.org

Also of note, Jacobs Free School at the corner of Pitt and Oronoco streets opened in January 1864. Supported by the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society and the local Black community, the school was named in honor of formerly enslaved activist, teacher, and author Harriet Jacobs and her daughter Louisa. Both worked diligently, along with Sarah V. Lawton (born free in 1846 in Massachusetts), in the education of freedpeople, with 170 students in attendance in December 1864 and 135 students the following June.[lxi]

Additional educational opportunities presented themselves at the local churches. Four new religious institutions under the sponsorship of African American clergy sprang up in Alexandria during the war. The newly formed congregations joined the antebellum Alfred Street Baptist and Roberts Memorial United Methodist churches, which continued to flourish in their neighborhoods, drawing freedmen and refugees into their spiritual circle and providing charitable aid to those in need.[lxii] Established in October, 1863, Beulah Baptist Church on S. Washington Street was the first formed after the military seized control.[lxiii] Over the next few years, three other new churches would be established to address spiritual, educational, and social needs: Third Baptist Church at Pitt and Oronoco streets, Shiloh Baptist Church at what would become the L’Ouverture Hospital complex, and Zion Baptist Church on South Lee Street. All were closely tied to promoting educational opportunities. An 1871 U.S. Department of Education report noted that “these churches have each a flourishing Sabbath school, in which old and young unite in learning to read and in the study of the Bible.”[lxiv]

Source: Google Maps image (enhanced)

Source: Alexandria Black History Museum

The 1871 Department of Education report further documents the success of the school programs. Between 1861 and 1864, 3,732 Black students registered for school, with 1,734 able to read by war’s end in 1865.[lxv] Educational opportunities continued after the war under the direction of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (Freedmen’s Bureau). In the summer of 1865, a section of L’Ouverture Hospital complex served as a school for the freedmen.[lxvi] Nearly one year after the war’s end, with the city still under martial law, Alexandria was home to four large African American schools, “with from two to five teachers each,” as well as several private schools, “with a total attendance of over a thousand scholars.”[lxvii]

In 1866 and 1867, the Freedmen’s Bureau contracted with George Lewis Seaton for the construction of two new schools for African American children – the Snowden School for Boys (also called the Seaton School) and the Hallowell School for Girls. Seaton, a master builder and prominent free Black Alexandrian before the war, advocated for the education of African American students and would go on to serve in the Virginia’s House of Delegates during Reconstruction. The schools, which opened in 1867 with the closure of the educational facilities at L’Ouverture. subsequently became part of the city’s public school system organized in 1870.[lxviii]

Footnotes

[i] Judge John C. Underwood to William Syphax, Letter, 12 July 1865, reprinted in Alexandria Gazette, 18 July 1865, 2.

[ii] William F. Smith and T. Michael Miller, A Seaport Saga, Portrait of Old Alexandria, Virginia (Norfolk: The Donning Company 1989), 84.

[iii] “Alexandria Under Occupation,” New York Herald-Tribune, 19 July 1861, 6.

[iv] Tim Dennée and Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, 0-59, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 7, freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf

[v] William F. Smith and T. Michael Miller, A Seaport Saga, Portrait of Old Alexandria, Virginia (Norfolk: The Donning Company 1989).

[vi] Tim Dennée and Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 7-8, freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf; Alexandria Gazette, 6 October 1862; Personal Papers of Medical Officers and Physicians Prior to 1912, Record Group 94, Entry 561, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[vii] Tim Dennée and Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 8, freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf; Alexandria Gazette, 6 October 1862; Personal Papers of Medical Officers and Physicians, Record Group 94, Entry 561, National Archives and Records Administration.

[viii] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 2; Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 6 May 1863, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf.

[ix] “Complaints at Alexandria,” New York Tribune, vol. XXI, no. 6274, 31 May 1861, 4-5; Franklin H. Barroll, 2nd Infantry, US Artillery, 16 September 1862, Record Group 393, Entry 5382, M5, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; “Ill Treatment,” Daily News, Vol. 1, No. 137, Alexandria, VA, 15 September 1862, archived with Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 5382, M5, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[x] Franklin and Armfield Office, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 1976, Section 8, 2, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/100-0105_FranklinArmfieldOffice_1976_Nomination.pdf, Benjamin A. Skolnik, Building and Property History, 1315 Duke Street, Alexandria, Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, Virginia, January 2021, 6, media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/archaeology/1315dukestbuildinghistoryskolnik2021.pdf; Janice G. Artemel, Elizabeth A. Crowell, and Jeff Parker, The Alexandria Slave Pen: The Archaeology of Urban Captivity, Engineering-Science, Inc., Washington, D.C., 1987, 41-47, media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/archaeology/sitereportartemel1987slavepenax75.pdf.

[xi] Alexandria Gazette, 26 August 1862.

[xii] Friends Intelligencer: A Religious and Family Journal, vol. 21 (Philadelphia, PA: Emmor Comly, 1865), 581.

[xiii] Judge John C. Underwood to William Syphax, Letter, 12 July 1865, reprinted in Alexandria Gazette, 18 July 1865, 2.

[xiv] Stefan Comibert, “Freedman's Village: a lost chapter of Arlington's Black History.” The Connection Newspapers, October 1, 2004.

[xv] Krystyn Moon, Finding The Fort: A History of an African American Neighborhood in Northern Virginia, 1860s-1960s, prepared for Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, 2014, 25-31.

[xvi] Jennifer Fleischner, Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship Between a First Lady and a Former Slave (New York: Broadway Books, 2003), 241.

[xvii] Herman Haupt, Reminiscences of General Herman Haupt (Milwaukee, WI: Wright & Joys Co., July 1901), 319.

[xviii] “Local News,” Alexandria Gazette, 10 January 1865.

[xix] Ulysses D. Eddy to Amiel W. Whipple, Alexandria, VA, 19 June 1862, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, 1821-1920, Record Group 393, Entry 6760, 12, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xx] William C. Gunnell, Chief Engineer, Report to Department of Quartermaster’s Office, Washington, D.C., 6 October 1862, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Record Group 77, Entry 556, 82, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxi] C.J. Sibley, Department of Quartermaster to Quartermaster General’s Office, Washington, D.C., 24 October 1862, Records of the Quartermaster General’s Office, Record Group 77, Entry 556, 444, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxii] William C. Gunnell, Chief Engineer, Report to Department of Quartermaster’s Office, Washington, D.C., 22 October 1862 Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Record Group 77, Entry 556, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Daniel H. Rucker to Department of Quartermaster’s Office, Washington, D.C., 22 October 1862, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Record Group 77, Entry 553, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; and Daniel H. Rucker to Department of Quartermaster’s Office, Washington, D.C., 10 November 1862 and 28 November 1862, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Record Group 77, Entry 556, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxiii] William Armstrong, Fort Ward, to Daniel Casper, Fredericksburg, OH, Letter, May 27, 1864, Dorothy Starr Civil War Research Library, Fort Ward Museum and Historic Site, Alexandria, VA.

[xxiv] Barton S. Alexander to John G. Barnard, Alexandria, VA, 20 October 1862, Letter H1620 and related correspondence A88, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, 1821-1920, Record Group 393, Part 1, Entry 5382, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxv] Herman Haupt, Reminiscences of General Herman Haupt (Milwaukee, WI: Wright & Joys Co., July 1901), 319.

[xxvi] Cited in Ira Berlin, Steven F. Miller, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, editors, Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867, Series I, Volume II, The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Upper South (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 250.

[xxvii] William C. Gunnell, Chief Engineer, Report to Department of Quartermaster’s Office, Washington, D.C., 25 November 1863, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Record Group 77, Entry 556, 160, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxviii] Cited in Ira Berlin, Steven F. Miller, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, editors, Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867, Series I, Volume II, The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Upper South (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 250.

[xxix] Ulysses D. Eddy to Amiel W. Whipple, Alexandria, VA, 25 August 1862, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, 1821-1920, Record Group 393, Part 2, Entry 6760, 33; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxx] Harriet Jacobs to Mrs. L. Maria Child, 26 March 1864, reprinted in National Anti-Slavery Standard, “Letters from Teachers of the Freedmen,” 16 April 1864.

[xxxi] Amy Bertsch, “Slaves at Volusia: Photographs of Felix Richards’ Slaves near Alexandria, Virginia,” 11 April 2010, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xxxii] Jean Fagan Yellin, editor, The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, Volume 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

[xxxiii] Harriet Jacobs to Mrs. L. Maria Child, 26 March 1864, reprinted in National Anti-Slavery Standard, “Letters from Teachers of the Freedmen,” 16 April 1864.

[xxxiv] Testimony of Captain John C. Wyman, “An Official Inquiry into the Conduct of The Reverend Albert Gladwin, Superintendent of Contraband at Alexandria, Virginia;” October, 1863, archived in Office of the Adjutant General Colored Troops Division 1863, Record Group 94, G26-83, Box 15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., compiled by T. Michael Miller, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, 2004.

[xxxv] John Carpenter, 21 October 1862, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, Record Group 92, Entry 225, Alexandria file, boxes 22-23, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxvi] Julia A. Wilbur to Mrs. Amy Kirby Post, 5 November 1862, Family papers of Isaac and Amy Kirby Post, 1817-1918, Rush Rhees Library, The University of Rochester, New York.

[xxxvii] Chauncey M. Keever, 8 December 1862, Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 5382, M130, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxviii] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 27 February 1863, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf.

[xxxix] The Shiloh Baptist Church History indicates that the church was established in March 1863 in the mess house of L’Ouverture Hospital, but Quartermaster documents indicate that this structure opened in 1864. Shiloh Baptist Church, Founding Our Church, 6144c7c0bc57920d7b57bf6d_History_-_Founding_Our_Church.pdf (website-files.com)

[xl] Sarah Traum, Brian Corle, and Joseph Balicki, Documentary Study, Archaeological Evaluation and Resource Management Plan for 1323 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA, John Milner Associates for Harambee CEDC, 2007, 27, on file at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, VA.

[xli] Shiloh Baptist Church, Founding Our Church, 6144c7c0bc57920d7b57bf6d_History_-_Founding_Our_Church.pdf (website-files.com)

[xlii] H.H. Wells, Acting Provost Marshal, May 1863, Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821-1920, Record Group 393, Entry 5386, W159, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xliii] “The Contrabands,” Alexandria Gazette, 18 December 1863.

[xliv] Findings of Captain W. McL. Gwynne, “An Official Inquiry into the Conduct of The Reverend Albert Gladwin, Superintendent of Contraband at Alexandria, Virginia,” archived in Office of the Adjutant General Colored Troops Division 1863; Record Group 94, G26-83, Box 15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C, compiled by T. Michael Miller, on file Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, 2004.

[xlv] “Local News,” Alexandria Gazette, 10 January 1865.

[xlvi] “Local News,” Alexandria Gazette, 10 January 1865.

[xlvii] Jean Fagan Yellin, editor, The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, Volume 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008); Letter from Harriet Jacobs, quoted in “Report of Friends” Association for the Aid and Elevation of Freedmen, 23 May 1864, 573-575.

[xlviii] “Alexandria Affairs,” Evening Union, Washington, D.C., 26 August 1864.

[xlix] Jean Fagan Yellin, editor, The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, Volume 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008); Letter from Harriet Jacobs, quoted in “Report of Friends” Association for the Aid and Elevation of Freedmen, 23 May 1864, 573-575.

[l] U.S. Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), 201; cited in Alexandria African American Trail, African American Neighborhoods, .

[li] Harriet Jacobs to Mrs. L. Maria Child, 26 March 1864, reprinted in National Anti-Slavery Standard, “Letters from Teachers of the Freedmen,” 16 April 1864.

[lii] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va., Library of Virginia, Richmond, Accession Number 1100408.

[liii] Julia A. Wilbur to Mrs. Anna M.C. Barnes, 20 November 1863, Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society papers, 1851-1868, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

[liv] “Alexandria Affairs,” Evening Union, Washington, D.C., 26 August 1864.

[lv] Cited in Jean Fagan Yellin, editor, The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, Volume 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 586.

[lvi] American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, 22 June 1864, 19, Report of the Secretary of War, communicating in compliance with a resolution of the Senate on the 26th of May; S. Exec. Doc. 53, Washington, 1864.

[lvii] Cited in Rev. Lewis C. Lockwood, "Appendix," Mary S. Peake, the Colored Teacher at Fortress Monroe, American Tract Society, 1862, 53-64, reprinted in An American Antiquarian Society Online Exhibition, 2006, americanantiquarian.org/Manuscripts/marypeakeappend.html.

[lviii] U.S. Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), 287.

[lix] U.S. Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), 285-287.

[lx] United States Department of Education, “Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia,” 287-8. Collier was the daughter of William Collier, himself a pioneering city missionary. The vital records for Massachusetts do not mention a cause of death or place of burial for Mary Collier, who died December 25, 1866 at the age of 56 in Alexandria.

[lxi] Dorothy Sterling, editor, We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997), 247-248.

[lxii] U.S. Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), 291.

[lxiii] The Afro-American Institute for Historic Preservation and Community Development, “A Study of Historic Sites in the Metropolitan Washington Region of Northern Virginia and Southern Maryland Importantly related to the History of Afro-Americans: Beulah Baptist Church,” Washington, D.C., August 1978, 97, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[lxiv] U.S. Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), 291.

[lxv] U.S. Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), 292.

[lxvi] Reverend James I. Ferree to Major General O.O. Howard, 18 August 1865; Records of the Field Offices of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, Letters Sent July 1865-July 1867; Record Group 105, Entry 3847; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[lxvii] The Freedmen’s Records, vol. II, no. 2 (Boston, MA: New England Freedmen’s Aid Society, February 1866).

[lxviii] Peter Bernstein, The Life and Times of George Lewis Seaton, Alexandria Archaeology Publication no. 121, 2001, 17, Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.