Cemetery: Preservation and Memorialization

Cemetery: Preservation and Memorialization

[W]e meet today to right these injustices and to honor the unique travails and contributions of the thousands of Americans whose remains rest in the Freedmen’s Cemetery. We encourage additional steps to protect and preserve this vital part of Alexandria’s historical legacy[i].

T. Michael Miller, City Librarian and Research Historian, Memorial Day, 1998

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

The establishment of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial reclaimed the site as a sacred place to ensure future protection of all graves and to honor the memory of those buried in Alexandria in their journey to be free. By the end of the 20th century, public knowledge of the burial ground at the corner of S. Washington and Church streets had faded. Headboards and fencing indicative of a cemetery had decayed a century earlier and the construction of roads and buildings had further obliterated any physical evidence of the property’s heritage. The process of preservation and memorialization spanned nearly three decades. It began in 1987 with the work of T. Michael Miller, an Alexandria City librarian and research historian who discovered nineteenth-century newspaper articles indicating the location of the nearly forgotten burial ground beneath a gas station and office building at the southwest corner of S. Washington and Church streets.

Alexandria has long been a city that values its history. In 1946, the city created one of the earliest nationally recognized historic districts in the nation. Alexandria Archaeology, a division of the city government, had its roots in the 1960s and ‘70s when construction activities threatened to destroy archaeological features buried near City Hall. It now oversees the Archaeological Protection Code, enacted in 1989 to ensure that information about the city’s past will not be lost due to development. In 1982, the city established the Alexandria Black History Museum with its current mission to enrich the lives of Alexandria's residents and visitors, to foster tolerance and understanding among all cultures, and to stimulate appreciation of the diversity of the African American experience. Clearly, the framework for understanding the significance of Miller’s find was embedded in the culture of the historic community.

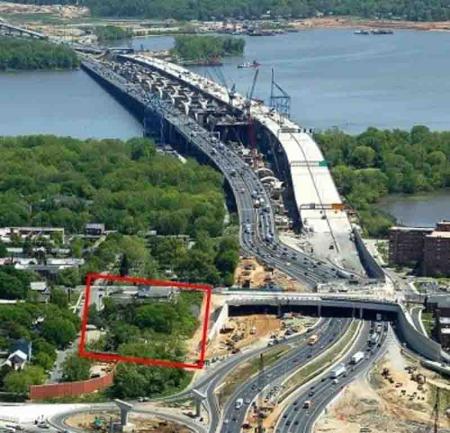

In 1989, just a few years after Miller’s discovery, the Federal Highway Administration began to develop plans for the replacement of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, which crossed the Potomac River in the vicinity of the site. Implementation of federal (and city) preservation laws required the evaluation of the effects of the bridge project on nearby historic properties. This work brought the cemetery back into the public’s consciousness and fostered a movement to restore dignity and recognition to those interred on the property.[ii] Community activists Lillie Finklea and Louise Massoud played a significant role in the surge of public awareness with their founding of the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery in 1997 and their subsequent successful lobbying efforts for the development of a memorial that would ensure protection of all graves that were still extant on the site. Under the umbrella of a partnership of federal, state, and city governments, historians, archaeologists, designers, engineers, and others worked together with the community to create a memorial that would ensure that the story of Freedmen’s Cemetery would not be forgotten again.

Archaeological work was integral to the design and development of the memorial to ensure protection of the graves. Agreements were put in place stipulating that no graves would be disturbed during the project. Excavation plans called for the discovery of as many grave locations as possible. It was equally important to determine where no graves were present so that designers would know where construction activities could take place. By the time the archaeological work was completed, 631 grave locations had been identified on the site.

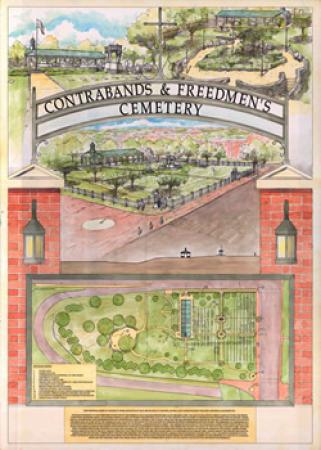

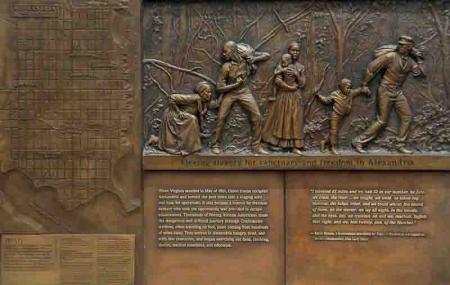

A community advisory group developed guidelines for creation of the memorial, generally echoing principles proposed earlier by the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery. In 2008, the city held a competition for the memorial design. Final plans by AECOM and Howard + Revis Design incorporated elements of C.J. Howard’s winning entry, as well as features of the second- and third- place submissions. In accordance with the guidelines, a stone marks each of the 631 graves locations identified by archaeologists, ensuring future protection of burials. The metal “picket” fence hearkens back to the likely white picket enclosure of the historical era. Remnants of past disturbances serve as reminders of periods of neglect and desecration. An interpretive marker highlights the successful civil rights protest of the USCT that led to a policy ensuring that African American soldiers who died in Alexandria would be laid to rest in the military cemetery in honor of their service. The Place of Remembrance serves as a haven for reflection and connection to the past, featuring bas-reliefs by Joanna Blake that depict the race to freedom and the importance of education to the freedom-seekers.

The fortuitous rediscovery of the Book of Records at the Library of Virginia in 1995 by historian Wesley Pippenger provided the names of the freedmen who were buried at the site, ultimately allowing for recognition and memorialization of individuals who sought freedom in Alexandria. A reproduction of the pages of the Book of Records etched into bronze plaques is the dominant feature of the Place of Remembrance. More than 150 of the names contain a marker, reading “Living Descendant Found,” the result of research conducted by genealogist Char McCargo Bah.

On September 6, 2014, a dedication ceremony marked the official opening of the memorial. Hundreds of family members of those buried in Freedmen’s Cemetery more than 145 years earlier entered the site. They placed roses on the base of the central sculpture, The Path of Thorns and Roses, which reflects the journey of those in search of freedom.

Source: Alexandria Black History Museum, City of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Convention and Visitors Association, photo by L. Barnes.

Historical Research

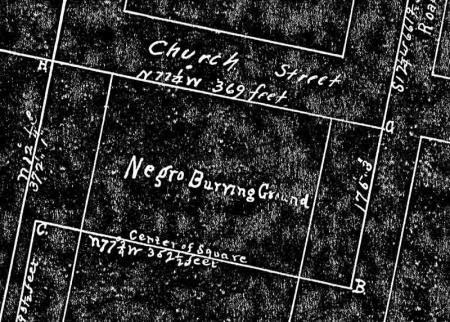

Two chance discoveries of historical documentation on Freedmen’s Cemetery proved seminal for the establishment of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial as it exists today. In 1987, T. Michael Miller, City of Alexandria research librarian, discovered the late 19th-century newspaper articles that indicated the presence of a burial ground for freedom-seekers established during the Civil War opposite the city’s Catholic Cemetery.[iii] The finds led to the discovery of other articles and historic maps that corroborated the location of the cemetery at the intersection of S. Washington and Church streets and allowed Miller to create the first timeline on the history of Freedmen’s Cemetery. The subsequent inclusion of the site in the Virginia Abandoned Cemetery Survey in 1989 and in the Historic Preservation Chapter of the Alexandria City Master Plan in 1992 ensured that despite the previous construction of a gas station and two-story building, any future developments would need to contend with the preservation of graves that could remain in situ on the property.

While Miller’s historical sleuthing revealed the all-important location of this significant site, a discovery in 1995 by research historian Wesley E. Pippenger in the Library of Virginia had a profound effect on the memorial’s design and emotional impact. While conducting research in the library in Richmond, Pippenger came upon the Book of Records with its listing of the names of the individuals buried at the cemetery, their ages, places of residence, etc. He published a transcription of the names in alphabetical order with all associated data.[iv] The addition of this personal information provided the basis for geographic and demographic studies and allowed for the establishment of genealogical connections to the present that have enriched the story of Freedmen’s Cemetery.

Source: Wesley Pippenger, Alexandria, Virginia Death Records 1863-1868 (The Gladwin Record) and 1869-1896, Family Line Publications, Westminster, MD, 1995

Woodrow Wilson Bridge Improvement Project

The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 requires that all federal projects consider the effects of development on significant historical and archaeological sites. The compliance process includes identification of historic properties, assessment of adverse effects on identified properties, and resolutions to avoid or mitigate recognized adverse effects.[v] In 1989, shortly after Miller discovered the documents that revealed the location of Freedmen’s Cemetery, federal plans for the improvement of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge over the Potomac River on the Capital Beltway got under way.[vi] As plans progressed, the Federal Highway Administration, the lead agency for the project, established a coordination committee in 1992 to deal with the potential effects of the changes to the bridge on the environment and cultural properties in the affected jurisdictions. Representatives from the City of Alexandria as an affected community and the Virginia Department of Transportation as the bridge construction leader for the state served on the committee.[vii]

Source: Woodrow Wilson Bridge Improvement Project, Federal Highway Administration

The Initial Role of Archaeology

The effects of the project on Freedmen’s Cemetery became a concern as alternatives for construction, staging, and mitigation were considered.[viii] Miller’s locational information, placing the site adjacent to, and perhaps partially within, the right-of-way for the Capital Beltway as it led to the bridge, became integral to implementation of the federal preservation laws. However, a determination of the effects of the project on the cemetery required additional historical study as well as archaeological investigations to delineate the boundaries of the site and to determine if burials were still present. The Virginia Department of Transportation hired a consultant to conduct this work.

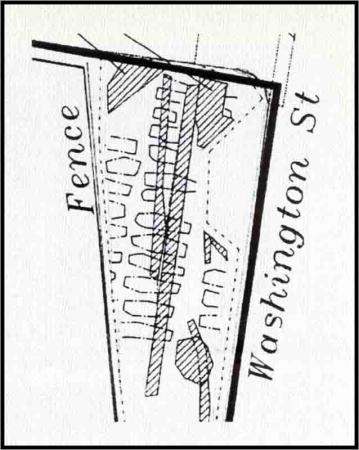

The historical study of the site provided the first evidence of a deed that mentioned the location of the cemetery; it was cited as a “Negro burying ground” in an 1875 land transaction that recorded the sale of the brickmaker’s property to the north.[ix] Moreover, map overlays showed that the Smith property taken for the creation of the cemetery contained the gas station and office building lots, extended into what is now the middle of S. Washington Street, and included land owned by the Virginia Department of Transportation, part of the project area for bridge development in the right-of-way for the Capital Beltway.

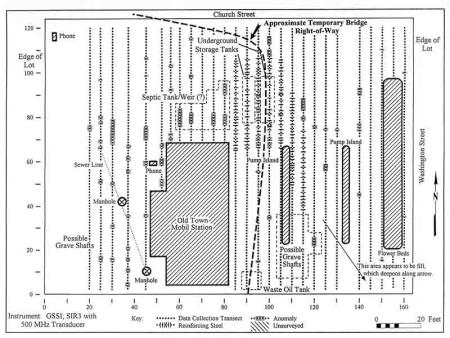

The first archaeological testing occurred in 1996 and took the form of remote sensing to investigate the possible presence of graves in the gas station lot. Remote sensing technologies (in this instance, ground-penetrating radar and electromagnetic sensitivity) attempt to determine previous ground-disturbing activities, such as digging for graves, without excavating into the layers of soil. This non-invasive procedure revealed patterns of anomalies in rows that suggested that burials were intact under the asphalt of the gas station lot. As a result of this work, Freedmen’s Cemetery was recognized for its historical significance and archaeological potential and deemed eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.[x]

With this establishment of the significance and archaeological potential of the cemetery, the Woodrow Wilson Bridge team executed a Memorandum of Agreement in 1997 indicating:

The Project shall be designed to avoid all temporary and permanent impacts to the Freedmen’s (Contraband) Cemetery.[xi]

This stipulation was reiterated in a Memorandum of Understanding in 2004.[xii] It meant that no graves could be disturbed during the development of the site and applied to archaeological work as well as construction activities. As a result, archaeologists implemented methods to allow for identification of grave locations without disturbance to the burials; no graves would be excavated.

Initial plans called for the creation of a small memorial on the Virginia Department of Transportation portion of the cemetery. Traditional archaeological testing in 1999-2000 identified 78 grave locations in the southern part of the site within the Virginia Department of Transportation section as well as under the sidewalk. Four of the graves discovered under the sidewalk originally extended into the roadway of what is now S. Washington Street.[xiii]

Source: J. Sanderson Stevens, Diane E. Hallsall, and Ronald J. Bowers, Addendum: Woodrow Wilson Bridge Improvement Study Documentary Research and Remote Sensing Investigations, Freedmen’s or Contraband Cemetery, Alexandria, Virginia, Parsons Engineering Science, Inc., Fairfax, Virginia, 1997

Source: Alexandria Deed Book 65:589, 26 December 1916, Alexandria Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA.

Source: Bernard W. Slaughter, George L. Miller and Meta Janowitz, Archaeological Investigations to Define the Boundaries of Freedmen's Cemetery (44 AX179), Within the Property owned by the Virginia Department of Transportation Alexandria, Virginia, The Potomac Crossing Consultants, 2001

The Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery

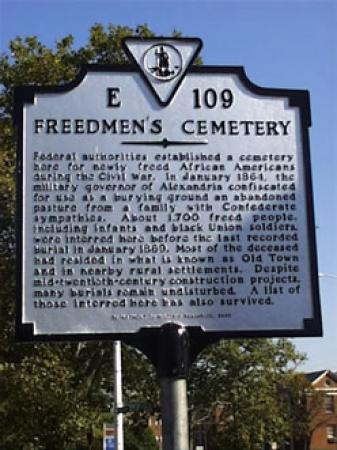

The tangible evidence of the presence of graves sparked a movement by community activists to call for purchase of the privately-owned gas station and office building lots so that the entire cemetery could be protected and preserved. The role played by the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery in the cemetery memorial project cannot be overstated. Alexandria residents Lillie Finklea and Louise Massoud founded the group after reading about the “the burial ground known as the Freedmen’s or Contraband Cemetery” in a Washington Post article in January 1997. Incensed that a gas station had been built on the site of an African American cemetery and amazed that they lived nearby, yet had no idea of the existence of the burial ground, Finklea and Massoud set up the organization with the purpose of preserving, commemorating, and researching the property. Coordinating with the city, the Friends focused their initial efforts on memorial ceremonies to honor Alexandria’s freedpeople and to raise public awareness of the location and condition of the nearly forgotten cemetery. A candle-lighting ceremony on Veterans Day in 1999 served as a reminder of the USCT who had originally been interred on the lot. Over the course of the next year, the group produced a brochure on the site’s history and helped prepare an exhibit at the Alexandria Black History Museum. In 2000, they also succeeded in obtaining a Virginia highway marker for the site.[xiv] That same year, Alexandria City Council adopted a resolution that the week of May 25-31 would be a Week of Remembrance, “in memory of the African American slaves who sought haven in our city and their descendants and those who seek freedom from injustice throughout the world.”

With the dream of a memorial on the entire cemetery property and with the knowledge that graves remained on the site, the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery expanded their work to include lobbying efforts that culminated in the decision for acquisition and enhancement of the privately owned sections of the cemetery to mitigate the effects of the bridge construction. As a result of a Settlement Agreement among the City of Alexandria, the Federal Highway Administration and the Virginia Department of Transportation, City Council adopted a plan in August 2002 to purchase the gas station and office building lots, setting in motion the local, state, and federal partnership that led to creating the memorial on the full area of the site and ensuring the protection and preservation of the entire cemetery.

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Guidelines for Memorial Creation

With plans for the purchase underway, the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery coordinated with the city’s Archaeological Commission, turning their efforts toward the development of principles for the creation of the memorial. Formulated in the fall of 2002 and sent to the Woodrow Wilson Bridge project manager for the Federal Highway Administration in early 2003, the principles included three primary goals:

- protection and stewardship of the cemetery and possible 1,800 graves;

- commemoration of Alexandria’s freed people; and

- increased public knowledge and awareness of the cemetery and the experience of the African Americans who fled to Alexandria as refugees seeking freedom from slavery during the Civil War.[xv]

The Friends’ vision for the design included principles for interpreting the site, calling for compatibility of all features, especially a surrounding fence, with the historic character of the cemetery. Other interpretive principles recommended the incorporation of public art as a focal point for the design; inclusion of a memorial wall reproducing the Book of Records and listing the names and ages of those buried in the cemetery in chronological order of death; marking all known grave locations with stones, flush to the ground; and historic interpretation using signs and to address topics such as the cemetery’s history, health and living conditions of the freedmen in Alexandria, and acknowledgement of the number of children who passed away.

Principles for design further stipulated that archaeological work be conducted to produce a survey map showing the extent and exact locations of burials before development of the memorial design. The survey information was needed both to inform the design process so that disturbance to graves could be avoided during development of the memorial and to allow for precise placement of the flat markers. Implicit in this latter stipulation was the obligation to guarantee the future protection of the graves and to ensure that the sacred nature of the site would never again be forgotten.

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Memorial Design and Development: The Process

As the Woodrow Wilson Bridge project progressed, the principles set forth by the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery became integral to the design and development of the memorial. In compliance with federal regulations requiring public input and involvement, the project formed the Freedmen’s Design Steering Committee, a community advisory group to work with city staff and memorial designers throughout the planning, construction, and dedication stages of the project. Drawn from representatives of the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, the Alexandria Archaeological Commission, the Society for the Preservation of Black Heritage, and other relevant city groups and commissions, the advisors took on the task of reviewing the design and interpretive plans for the memorial and incorporated many of the principles of the Friends’ group into their oversight requirements.

While remote sensing had indicated the possible presence of graves on the gas station and office building lots, the city required confirmation prior to purchase. City archaeologists conducted the required archaeological testing in 2004 and identified 45 additional grave locations on these parcels, bringing the total number to 123.[xvi] Confirmation of the presence of burials on the privately-owned lots led to negotiations with their owners. In 2007, the City of Alexandria purchased the gas station and office building properties with funding allocated from the Virginia Department of Transportation as part of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge Improvement Project.

Source: Contrabands and Freedmen’s Cemetery Memorial Design Competition, City of Alexandria, EDAW/AECOM

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Archeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Rededication as a Sacred Place

The establishment of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial began in earnest with the purchase of the gas station and office building properties. The project envisioned by the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery was to become a reality. City archaeologists monitored the demolition of the structures in preparation for the cemetery’s rebirth as a solemn place of dignity and respect. On May 12, 2007, the City of Alexandria reclaimed the property as a sacred site in a rededication ceremony, dubbed “Alexandria Freedmen’s Cemetery, 1864-1869,” attended by more than 500 residents and visitors. The program included music, speakers, and the poignant reading of names and ages of individuals buried on the site. In the months leading up to the rededication, Alexandria schoolchildren and others designed luminary bags, each marked with the name and age of a person interred in the cemetery and signed by the artist. Now archived by the city, the luminaria were lit and placed on the grounds of the cemetery during the rededication ceremony. Their presence brought those whose names had been nearly forgotten back to their rightful place in history.

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Genealogical Research

No known descendants attended the rituals at the rededication ceremony. However, the listing of names in the Book of Records provided a unique opportunity to connect the past with the present. The city hired genealogist Char McCargo Bah to make those connections. Starting with the names, Bah poured over census and marriage records and other primary historical documents. Eventually, she found more than one thousand family members of more than 150 men, women, and children buried at Freedmen’s Cemetery during and immediately after the Civil War. Char McCargo Bah’s book, Alexandria's Freedmen's Cemetery: A Legacy of Freedom, published in 2019, imagines how those who did not live long in freedom might speak to their relatives living in today’s world.

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Intensive Archaeological Investigation

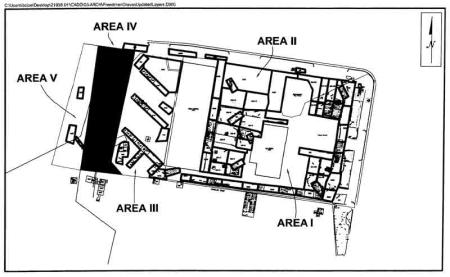

City archaeologists began intensive archaeological investigation after demolition of the structures, continuing from May through December 2007. The primary goals of the archaeological excavation focused on discovering the locations of graves so that they could be protected during construction and in perpetuity and identifying cemetery features that could be incorporated into the memorial design. To these ends, the excavations resulted in the production of a map showing where development could take place on the site. The map delineated the locations of the 534 graves identified up to that point, unexcavated locations where graves were likely, the location of the entry path into the cemetery that was discovered during the investigation, and most importantly, places where graves were not present - i.e. areas where memorial development activities would not cause disturbance to burials.[xvii]

Source: Sipe, Boyd, with Francine W. Bromberg, Steven Shephard, Pamela J. Cressey, and Eric Larsen, The Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial, City of Alexandria, Virginia. Archaeological Data Recovery at Site 44AX0179, Thunderbird Archaeology, a division of Wetland Studies, Gainesville, VA and Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, 2014.

Design Competitions

In 2008, after completion of the intensive archaeological fieldwork, the city held a competition for the design of the memorial. The call for entries presented a brief history of the site and reiterated many of the principles developed by the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery for memorial creation, stressing the need to avoid disturbance to graves. It included the map that provided information on the areas where development could occur.

The city received more than 200 design concepts from all fifty states and twenty countries. The Freedmen’s Steering Committee selected the design of architect C.J. Howard of Alexandria as the first-place winner. The final site plan, executed by AECOM, incorporated elements of the first, second, and third prize winners, and relied upon the archaeological work to determine placement of memorial features to avoid any disturbance to extant graves.

In 2011, the city organized a second competition for public art to honor the memory of the freedom-seekers who came to Alexandria. The Path of Thorns and Roses, a sculpture designed by Mario Chiodo, was selected to serve as a focal point to draw visitors into the memorial site.

Source: C.J. Howard poster, City of Alexandria

Construction and Final Archaeological Investigations

After years of archaeological preservation measures, public steering committee meetings, web-based design competitions, and public review of design and interpretation, construction of the memorial began in 2012. Archaeological monitoring and further investigation took place in concert with construction activities to ensure that graves would not be disturbed in previously unexcavated areas, particularly as the fence was put in place and as the sidewalk was replaced. The work led to the discovery of almost 100 additional grave locations, bringing the total number to 631.

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Memorial Dedication and Opening

The Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial was dedicated on September 6, 2014, described by one newspaper reporter as the culmination of “a 17-year multimillion-dollar effort to identify bodies, locate descendants and build a towering bronze memorial.”[xviii] The two days prior to the dedication ceremony featured lectures recounting the history of the property and the story of the memorial’s creation, walking tours through the neighborhoods where the newly arrived freedom-seekers and freedmen lived and died, a candlelight vigil, and a reiteration of a program titled “The Journey to be Free: Descendants Returning Home to Alexandria.” Originally performed in March as part of the National Civil War Project to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the conflict, the program sought to honor the lives and legacy of the African American people seeking freedom in the city.[xix] All the descendants identified by the research of Char McCargo Bah were invited to attend. On September 6, the dedication-day activities began with the tolling of bells throughout the city to honor those interred on the reclaimed land of the memorial. The ceremony included musical selections from the Alexandria Frist Baptist Church Adoration Ringers, the Alexandria City Employees Choir, and the Washington Revels Jubilee Voices. U.S. Representative Jim Moran gave the keynote address, followed by a poem from the city’s poet laureate Tori Lane, a reading by historian C.R. Gibbs, a reading by genealogist Char McCargo Bah, and a history of the cemetery by Mayor William Euille. Concluding the formal ceremony, members of the City Council and invited guests recited the names of the ancestors whose descendants were present for the dedication. After each name was called, Char McCargo Bah tolled the memorial bell, and each family was honored with the presentation of a red rose.

Descendants then led a procession into the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial to place the roses in memory of their ancestors, most of whom had arrived in Alexandria in search of freedom some 150 years earlier. Their footsteps reverberated on top of the location of the carriage path into the cemetery, the last leg of their ancestors’ journeys to their final resting places.

Source: Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Photo by Carol Bloom

The Final Design

The final design for the memorial incorporated many of the principles set forth by the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, modified and amplified in guidelines recommended by the steering committee. It is a place for reflection, commemoration, education, and the search for cultural identity. Archaeologists located 631 of the 1,711 graves known to be present on the site, both within the site and under the sidewalk along S. Washington Street. Each known grave is marked with a stone to restore dignity to the individuals buried here and to ensure future protection. Reminders of the disturbance and desecration that ensued following the abandonment by the federal government reenforce the message of the on-going need for vigilance to ensure future protection. The Path of Thorns and Roses, a bronze statue by Mario Chiodo, depicts the journey to freedom and equality and beckons visitors into the memorial. The arched entrance and the surrounding fence with its metal “pickets” evoke elements of the historical character of the site. The entry into the memorial appropriately lies above the location of the original path into the cemetery discovered during archaeological excavations. The path likely served as the route used by carriages to carry the deceased to their final resting places. A stone marker highlights the contributions of the United States Colored Troops and recounts the successful civil rights action that led to disinterment of USCT from Freedmen’s Cemetery and reburial in Alexandria’s National Cemetery to recognize and honor their service.

Stone walls border the Place of Remembrance where the names and ages of the deceased from the Book of Records are etched into bronze panels. Bronze icons mark those with known descendants. Genealogical research is on-going with icons installed as descendants are found, making this a living memorial. Bas-reliefs by artist Joanna Blake illustrate the race to freedom and the importance of education to the freedom-seekers. Interpretive panels provide context to the experiences of the African American individuals who made their way to the city in search of freedom.

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria Convention and Visitors Association, photo by L. Barnes

Continued Protection and Preservation

Stewardship of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial to prevent future disturbance to graves remains the responsibility of the City of Alexandria. The markers placed on known grave locations help to ensure that burial sites will be protected in the future and that the memory of the cemetery does not begin to fade away again. More importantly, the city has developed a stewardship plan that not only includes mapped survey information about all grave locations but also identifies the areas where additional, unmapped graves may remain. The official listings of the site on the National Register of Historic Places in 2012, the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom in 2015, and African American Civil Rights Network in 2021 promote public awareness of the site and its significance. An extra level of protection for the cemetery stems from the 2012 conservation easement given by the city to the Alexandria Historical Restoration and Preservation Commission, empowered by the Virginia Assembly in 1962 to ensure preservation of historical properties.[xx]

However, the establishment of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial can never erase the injustice caused by the neglect and desecration of more than a century. In the moment, the community and the city, state, and federal governments joined forces to right a wrong, to honor the memory of the freedom-seekers who came to Alexandria during the Civil War, to restore dignity to those buried in the cemetery, and to reclaim the site as a sacred place. Nevertheless, inequality still exists today in many forms in our communities and nation. Work must focus on eradicating injustice, such as racial profiling, inequities in our criminal justice system, and unequal access to wealth and resources. The future, as envisioned by Harriet Jacobs in 1864 and highlighted by the quote on the base of the statue, has not yet fully arrived:

I am thankful there is a beginning. I am full of hope for the future. A Power mightier than man is guiding this revolution; and though justice moves slowly, it will come at last.[xxi]

May remembrance and knowledge about the past from sites such as the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial foster the spirit, energy, and activism to make her dream a reality.

The City of Alexandria serves as the steward of the memorial to protect the graves and keep the memory of this sacred place alive.

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Footnotes

[i] T. Michael Miller, “A Time for Remembrance-The Contraband Cemetery,” Memorial Day Address at the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery, May 1998.

[ii] Alice Reid, “Cemetery Prompts Questions of Bridge” Washington Post, 30 January 1997, 1.

[iii] “Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post 29 March 1892; Alexandria Gazette, 5 January 1894.

[iv] Wesley Pippenger, Alexandria, Virginia Death Records 1863-1868 (The Gladwin Record) and 1869-1896 (Westminster, MD: Family Line Publications, 1995), Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408.

[v] National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, Pub. L. 89-665, enacted 15 October 1966, http://ncshpo.org/resources/national-historic-preservation-act-of-1966/, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/36/part-800/subpart-C.

[vi] Federal Highway Administration, “FHWA Leads the Planning Process for Redesign of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge,” https://fhwaapps.fhwa.dot.gov/planworks/Reference/CaseStudy/8.

[vii] Federal Highway Administration, “FHWA Leads the Planning Process for Redesign of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge,” https://fhwaapps.fhwa.dot.gov/planworks/Reference/CaseStudy/8.

[viii] Woodrow Wilson Bridge Improvement Study: Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Section 4(f) Evaluation, Prepared by the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Region 3 and Virginia Department of Transportation Maryland Department of Transportation, State Highway Administration, and District of Columbia Department of Public Works, July 1996, page 4-51 and table 4-23.

[ix] Fairfax County Deed Book, S4:194, 16 April 1875, Fairfax County Circuit Court Historic Records, Fairfax, VA.

[x] J. Sanderson Stevens, Diane E. Hallsall, and Ronald J. Bowers, Addendum: Woodrow Wilson Bridge Improvement Study Documentary Research and Remote Sensing Investigations, Freedmen’s or Contraband Cemetery, Alexandria, Virginia (Parsons Engineering Science, Inc., Fairfax, Virginia, January 1997, revised August 1997).

[xi] Memorandum of Agreement Among the Federal Highway Administration, National Park Service, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Maryland State Historic Preservation Officer, and Virginia State Historic Preservation Officer, Regarding the Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project on Interstate 95/435 in Virginia, Maryland and the District of Columbia (Project No. FHWA-MD-VA-DC-EIS-91-01-F), executed October and November 1997, 6.

[xii] Memorandum of Understanding among the Federal Highway Administration, Virginia Department of Transportation, and City of Alexandria Regarding the Alexandria Freedmen’s Cemetery, July 2007.

[xiii] Bernard W. Slaughter, George L. Miller, and Meta Janowitz (Potomac Crossing Consultants), Archaeological Investigations to Define the Boundaries of Freedmen’s Cemetery (44AX0079), Within the Property Owned by the Virginia Department of Transportation, Alexandria, Virginia, Potomac Crossing Consultants, 2001, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria VA.

[xiv] Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/.

[xv] Principles for Planning the Alexandria Freedmen’s Cemetery Park, Developed by the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery and the Alexandria Archaeological Commission, October 23, 2002, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xvi] Francine W. Bromberg and Steven J. Shephard, Alexandria Archaeological Testing of Freedmen’s Cemetery (44AX0179) Alexandria, Virginia, June 2004. Alexandria, VA: Alexandria Archaeology Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, VA, 2007.

[xvii] Boyd Sipe, et al., The Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial City of Alexandria, Virginia Archeological Data Recovery at Site 44AX0179, prepared for: U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration and Virginia Department of Transportation by Thunderbird Archaeology and Alexandria Archaeology, 2014, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xviii] Robert Samuels, “A Memorial Honors Slaves Who Escaped the South for Refuge in Alexandria, Va,” Washington Post, 6 September 2014.

[xix] “City of Alexandria and Arena Stage Co-Host Special Performance and “Community Conversation” Celebrating the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial.” City of Alexandria website, https://media.alexandriava.gov/archives/news/2014/02-26/76742/archive.html

[xx] “Deed of Conservation Easement Agreement,” 27 March 2012, City of Alexandria, Virginia, Liber 120007513, Folio 558.

[xxi] Harriet Jacobs and Louisa Jacobs to L. Maria Child, March 26, 1864, “Letters from Teachers of the Freedmen,” published in National Anti-Slavery Standard, 16 April 1864, transcription available at “Documenting the American South,” University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jacobs/support4.html