Cemetery: Administration and Appearance

Cemetery: Administration and Appearance

About one acre and a half of land belonging to Francis L. Smith of Alex’a, situated at the extreme South end of Washington Street, just beyond the city limits of Alex’a, was seized by the military authority as abandoned in January 1864, and by order of Brig. Genl. J.P. Slough, Military Governor of Alex’a, was fenced in, [and] assigned as a burial place for “contrabands”…[i]

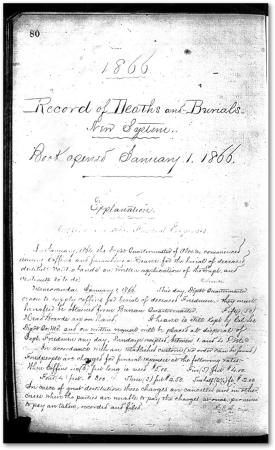

Captain Henry Alvord, Book of Records, January 1, 1866

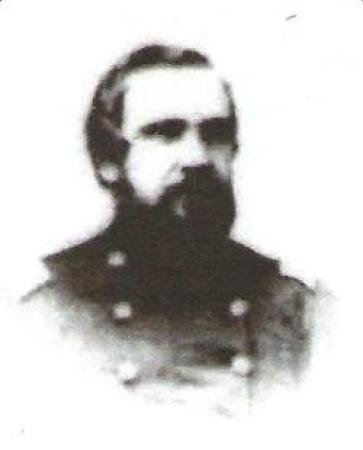

Source: Captain Henry Elijah Alvord, Wikipedia

On January 1, 1866, Captain Henry Elijah Alvord “opened” the Book of Records to facilitate the transfer of responsibility for the management of Freedmen’s Cemetery to his successor, the incoming Superintendent of Freedmen, Major Samuel Perry Lee.[ii] About six months earlier, during the first week of July 1865, Alvord had been assigned to Alexandria to begin a tour of duty as superintendent with the newly formed Freedmen’s Bureau in Virginia. With his arrival, administration of the burial ground had shifted from the U.S. Army to the Quartermaster’s Department of the Freedmen’s Bureau.[iii]

Captain Alvord’s explanations and descriptions in the Book of Records convey information about the establishment of Freedmen’s Cemetery, its administration since its founding, the on-going management processes and any changes to them, and the “Modus Operandi” for funerals so that they could continue without interruption under management by the Freedmen’s Bureau. From the Book of Records and other documentary sources, it becomes apparent that throughout the period of administration by the military and the bureau, the government continued to supply coffins and headboards for burials in Freedmen’s Cemetery and provided a hearse to transport deceased individuals to their final resting places. A listing of the names of those who passed away became part of the record, and headboards were prepared accordingly. Set procedures were established for scheduling and carrying out the funerals, including the hiring of laborers to prepare the graves and be present at the time of burials.

Although no known photograph of Freedmen’s Cemetery exists, clues to its appearance can be inferred from a photograph of Soldiers’ Cemetery taken during the war. The image of the military graveyard shows a white picket fence enclosing neat rows of graves marked by wooden headboards with black letters.[iv] Given that the Army established both burial grounds during the war and appears to have instituted some standardized administrative practices for managing them, Freedmen’s Cemetery likely exhibited similar features.[v]

Source: Book of Records, Library of Virginia, Richmond

Source: Major Samuel Perry Lee, Wikipedia

Source: Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Setting up the Cemetery: A Fence and Tool House

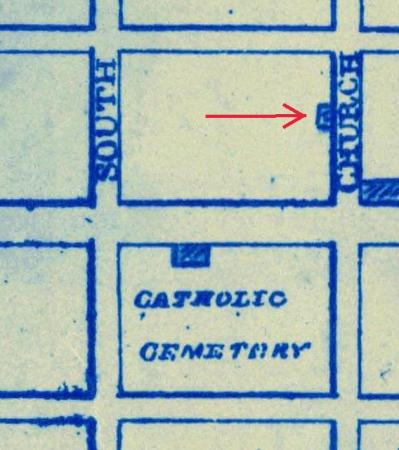

Source: Portion of "Plan of Alexandria" 1864, Office of Coast Survey Historical Map & Chart Collection, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association

The placement of a fence surrounding Freedmen’s Cemetery is mentioned in Alvord’s descriptions in the Book of Records[vi] and well documented in other historical records. On February 28, 1864, General Slough, the Military Governor of Alexandria, ordered Reverend Gladwin, the Superintendent of Contrabands, to construct the fence:

You will please superintend the building of a Fence around the Burying Ground recently selected. It is to be done as cheaply & expeditiously as possible.[vii]

In later correspondence with Slough, Gladwin recounted his receipt of the order and accomplishment of the task.[viii] It is likely that the enclosure around Freedmen’s Cemetery was similar to the white picket fence that originally surrounded Soldier’s Cemetery as depicted in a Civil War-era photograph.[ix]

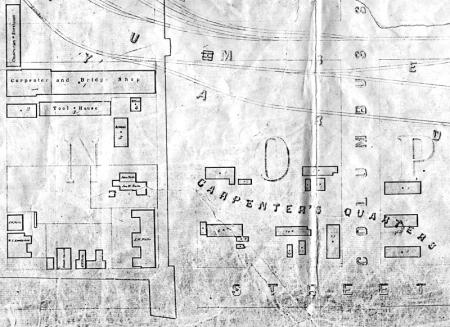

In addition to the fence, Alvord’s explanation in the Book of Records mentions the presence of “[a] small house for keeping tools and bier, also for shelter to grave diggers in inclement weather was built on the grounds.”[x] An 1864 map shows what is likely this small building located along the northern, Church Street-boundary of the site.[xi] The structure may have survived until 1877, depicted on an insurance map near the corner of Church and Washington streets.[xii]

Both the structure and enclosure were completed just five days after the first burial took place at Freedmen’s Cemetery. Gladwin authorized paying James Webster $51.75 on March 18, 1864, for “building [the] fence and tool-house at the new burying ground, commencing Feb. 29th and ending March 12th inst.”[xiii]

Provisions for Coffins and Headboards

Source: Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

The military government provided coffins for the freedom-seekers who were laid to rest in Freedmen’s Cemetery. Alvord documents the supply of coffins at the very beginning of his explanation in the Book of Records:

In January, 1864, the Depot Quartermaster of Alexandria commenced issuing Coffins and furnishing a Hearse for the burial of deceased contrabands on written application of the Supt. and continued to do so.[xiv]

His description of the administrative process prior to burial also provides definitive evidence for the use of headboards to mark the graves:

When a death is reported to the Supt. it is registered in the Record Book of Deaths and Burials….A HeadBoard is then prepared in accordance with the record. ….Head-boards are kept at Office of Supt. marked there and numbered in accordance with register.[xv]

The directive to “prepare the headboard” involved recording the names and dates of death in black lettering on the white boards. Headboards of soldiers who had served in the USCT and were originally interred at Freedmen’s Cemetery likely also indicated the company and regiment in which they served, as were those for soldiers buried at the national cemetery.[xvi] Thus, from the date of the establishment of Freedmen’s Cemetery until its final recorded burial in January 1869, Freedmen’s Cemetery probably contained neat rows of graves with headboards similar to those pictured in the Civil War photograph of the military burial ground.[xvii]

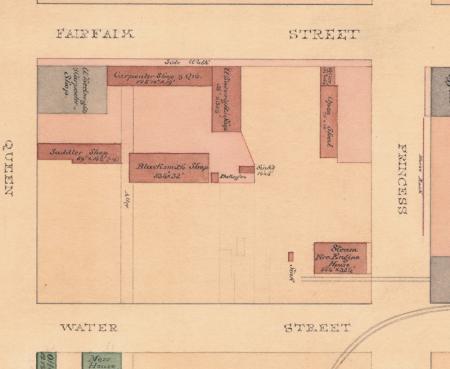

Carpenters at military government workshops, probably those on Fairfax between Queen and Princess Streets[xviii] or elsewhere in the city, manufactured and supplied the coffins and headboards for the freedom-seekers from January 1864 to January 1, 1866. This was also the probable source for the funeral needs for soldiers during this period. However, with the war over, these workshops closed on December 31, 1865, and the source for the coffin and headboard supply, at least for the freedpeople, shifted to carpentry workshops at Freedmen’s Village.[xix]

The continuing importance given to the provision of coffins and other funerary needs for the freedom-seekers can be inferred from another entry by Alvord in the Book of Records. While those who could pay for funeral services were to be charged according to the size of the coffin needed, the charges would be cancelled for those who could not afford the cost:

In accordance with an established custom (no order can be found) Freedpeople are charged for funeral expenses at the following rates:- When Coffins six (6) feet long is used $5.00. Five (5) feet $4.00. Four (4) feet, $3.00. Three (3) feet $2.50. Two half (2½) ft. $2.00. In case of great destitution these charges are cancelled and in other cases where the parties are unable to pay the charges at once, promises to pay are taken, recorded and filed.[xx]

Most of the formerly enslaved people and freedmen apparently took advantage of the government’s provision for supplying coffins for burials, but a few individuals may have either manufactured their own coffins or purchased them from local businessmen. Several entries in the Book of Records indicate “No coffin furnished” or “No coffin supplied.”[xxi]

Source: Wharves, Offices, and Storehouses, Office of the Quartermaster General, Record Group 92; U.S. Military Railroad Station, Office of the Chief Engineer and Genl Sup’t, Record Group 77, 1865; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

The Cemetery as Workplace

In addition to highlighting the supplies needed for burials, Alvord’s January 1, 1866, description in the Book of Records sheds light into practical aspects of conducting funerals, including the employment of African American men as gravediggers. The Superintendent of Contrabands hired three men in 1864 to perform this duty, and as reported by Alvord:

One of these men is at the Cemetery from daylight till dark daily and at 2 P.M. each day all are there to attend to burials. Graves are always kept prepared.[xxii]

Gravedigging remained a job for three people at Freedmen’s Cemetery until the dismissal of one at the time of Alvord’s writing, perhaps as a cost-saving measure. With rates of death falling throughout 1867, the Bureau discharged a second gravedigger, leaving a single individual in charge from September 1867 through the end of 1868.[xxiii]

The military government placed Randall Ward in charge of the work in 1864 at the time of establishment of the cemetery. He remained the official primary caretaker until December 1868, just before the end of the cemetery’s management by the Freedmen’s Bureau. Ward’s assistants over the years included Sam Baltimore, Isaac Fontleroy, John Parker, William Thomas, and Thomas Johnson. In October 1865, Ward was earning twenty-five dollars per month while his assistants earned twenty. About a year later, Ward’s monthly salary was reduced to twenty while Johnson, his remaining assistant, earned fifteen. Other African American individuals worked as hearse drivers to carry deceased individuals to their final resting places. John Wallace served in this capacity in September 1865, earning fifteen dollars for the month.[xxiv]

Burial Process and Funerals

The “Modus Operandi” section of the Book of Records provides insight into the other important procedures related to the burial process at Freedmen’s Cemetery. The scheduling of the burial depended on the time that the death was reported and registered in the record book:

If before 1 P.M. a request for a Hearse is sent to the Dépôt Quartermaster,—if after 1 P.M. funeral is postponed till next day. No funerals on Sunday.[xxv]

Explicit direction documented the path taken by the hearse and the orders that would be needed to conduct the funeral:

When the Hearse reports at office of Supt. [of Contrabands], the driver is given an order on Dr. Heard Surg. in charge of L’Ouverture Hospital for a coffin of the size required, also the Headboard and address of the party at whose house the corpse lies, also an order to [Randall] Ward in charge of burial ground, to bury remains, on the back of which must be as many crosses (X) as there are bodies to be buried.… Driver then proceeds to [L’Ouverture] Hospital [where the coffins were stored] gets coffin, goes to house where corpse is, receives it and proceeds to burial ground and then the funeral is attended to by the men in charge of the place.[xxvi]

Officiants and Memorials

Reverend Albert Gladwin, Superintendent of Contrabands, and his assistant, Reverend Eliphalet Owen, who recorded most of the names of the deceased listed in the Book of Records, served as officiants at some of the funerals at Freedmen’s Cemetery, occasionally accompanied by Reverend John Vassar, a missionary to the soldiers in the area. In addition, Reverends Peter Washington and Leland Warring, two prominent African American members of the community, conducted funeral services.[xxvii] Reverend Warring, a former teacher who had established one of the earliest schools for freedom-seekers in Alexandria in 1862, became the pastor for the Shiloh Baptist Church that began in the L’Ouverture Hospital complex. Reverend Washington, described as a recent licentiate in an 1863 newspaper article, worked in the household of Reverend Gladwin, while serving as a missionary to the freedpeople and often speaking at celebrations and recruiting meetings.[xxviii]

Reverend Washington passed away on 20 May 1864 and was buried in Freedmen’s Cemetery where he had served as an officiant at many funerals.[xxix] Julia Wilbur attended the reverend’s memorial:

[W]e remained here to witness the funeral of Peter W. The people assembled in the Yard, & the coffin was taken out there. It was quite an impressive scene.[xxx]

Also present, Harriet Jacobs joined the procession to the gravesite; her description of the funeral emphasizes the poignancy of Reverend Washington’s passing and the deference that others paid him. It provides one of the few known descriptions of a memorial service for a civilian who was buried in Freedmen’s Cemetery:

At half past two the people began to gather, and the hundreds that came were neat in dress and respectful in manners…. He had eight children; in one day he was bereft of his six daughters and five grandchildren. ‘On that day,’ said the minister, ‘he leant on me, and with a bursting heart exclaimed, “If it were not for my hope in Christ, I could not bear up under this trial….”’ No child of his came to bid him a last farewell, they are scattered I know not where: his two sons are in the army, battling for the country their father loved in spite of her persecutions to him and his.[xxxi]

Footnotes

[i] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 80.

[ii] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 80.

[iii] Elizabeth M. Crawford and Elizabeth L. Morgan, “Major Henry Elijah Alvord: Soldier, Farmer, Teacher”; “Miscellaneous War News,” Springfield (MA) Republican, July 8, 1865; Timothy Dennée, email communication with Francine Bromberg, 4 December 2019, research file available at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[iv] Alexandria, Va. Soldiers’ Cemetery, Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/cwpb.03928/

James M. Moore, Captain, Alexandria Quartermaster, “Extract from annual report of Captain James M. Moore, A.Q.M., relating to the national cemeteries and burials of deceased soldiers and others dying in the service of the United States in hospitals in and around Washington, D.C.” in Annual Report of the Secretary of War at the Second Session of the Thirty-Eighth Congress, House of Representatives Ex. Doc. No. 83, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1865), 168.. Note: This military report briefly documents management procedures for setting up the national cemeteries. The procedures implemented for Freedmen’s Cemetery appear similar to those at Soldiers’ Cemetery although the graveyard for the freedom-seekers would have lacked the “adornments” that were present in the military burial ground.

[vi] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 80.

[vii] General John P. Slough to Reverend Gladwin, 29 February 1864, Unregistered Letters Received March 1863 to April 1866, Record Group 105, Entry 3853, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C

[viii] Reverend Albert Gladwin to John P. Slough, 16 December 1864, Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2053, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C

[ix] Alexandria, Va. Soldiers’ Cemetery, Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/cwpb.03928/

[x] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 2.

[xi] "Plan of Alexandria" 1864, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Coast Survey Historical Map & Chart Collection File name:32-1-1864, http://historicalcharts.noaa.gov.

[xii] G.M. Hopkins, City Atlas of Alexandria, VA, (Philadelphia, PA: F. Bourquin’s Steam Lithographic Press, 1877).

[xiii] Reverend Gladwin to James Webster, Provost Marshal’s Office, 12 and 18 March 1864, Unregistered Letters Received March 1863 to April 1866, Record Group 105, Entry 3853, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xiv] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 80.

[xv] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 80.

[xvi] James M. Moore, Captain, Alexandria Quartermaster, “Extract from annual report of Captain James M. Moore, A.Q.M., relating to the national cemeteries and burials of deceased soldiers and others dying in the service of the United States in hospitals in and around Washington, D.C.” in Annual Report of the Secretary of War at the Second Session of the Thirty-Eighth Congress, House of Representatives Ex. Doc. No. 83, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1865), 168.

[xvii] Alexandria, Va. Soldiers’ Cemetery, Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/cwpb.03928/

[xviii] Wharves, Offices, and Storehouses, Map 111, Sheet 30, NAID109182974, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, Record Group 92, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xix] Charles Farnum to Henry Alvord, 15 December 1865, Unregistered Letters Received, Mar. 1863-Apr. 1866, Record Group 105, Entry 3853, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., cited in research by Timothy Dennée, file available Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xx] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 80.

[xxi] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, passim.

[xxii] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 81.

[xxiii] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 81; Unregistered Letters Received, Mar. 1863-Apr. 1866, Record Group 105, Entry 3878, cited in research by Timothy Dennée, research file available at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.; “Alexandria Annals,” Washington Post, 2 November 1880, 3.

[xxiv] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 81; Unregistered Letters Received, Mar. 1863-Apr. 1866, Record Group 105, Entries 456,3866 and 3878, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., cited in research by Timothy Dennée, research file available at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xxv] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 82.

[xxvi] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 82.

[xxvii] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, passim.

[xxviii] Daily National Republican, May 13, 1863; Julia A. Wilbur to Anna M.C. Barnes, 5 March 1864, Rochester Anti-Slavery Society papers, 1851-1868, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

[xxix] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 15, passim.

[xxx] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 21 May 1864, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf

[xxxi] Cited in Jean Fagan Yellin, editor, The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, Volume 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008); Harriet Jacobs Family Papers Project Records, 1890s-2005, Collection Number: 05464 Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.