Cemetery: Desecrated and Neglected -- Nearly Forgotten

Desecrated and Neglected -- Nearly Forgotten

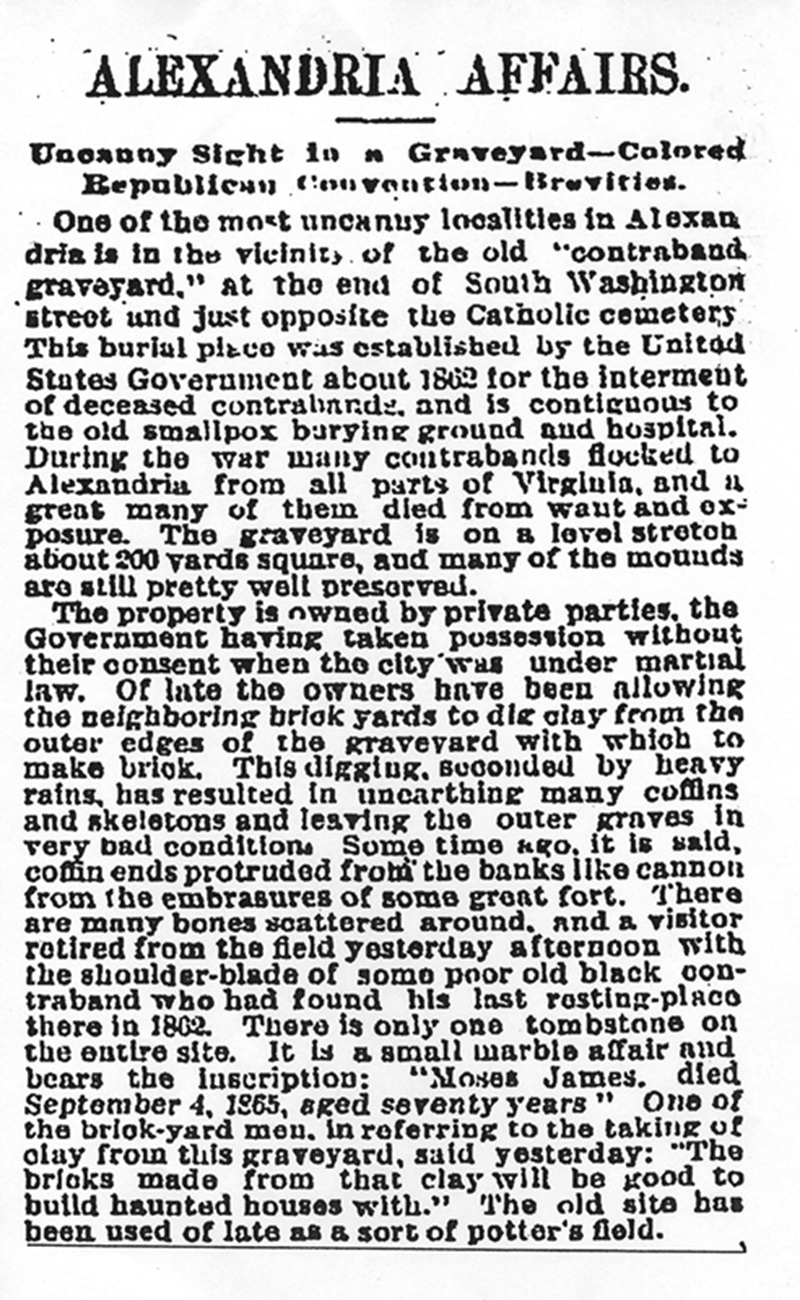

Of late the owners [of Freedmen’s Cemetery] have allowed the neighboring brick yards to dig clay from the outer edges of the graveyard with which to make brick. This digging, seconded by heavy rains, has resulted in unearthing many coffins and skeletons and leaving the outer graves in very bad conditions. Some time ago, it is said, coffin ends protruded from the banks like cannon from the embrasures of some great fort.[i]

“Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post, 29 March 1892

Management of Freedmen’s Cemetery by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands ceased as of January 1869 with no plans in place to care for or maintain the burial ground. However, there are indications that burials by community members may have taken place in the following decades and that family members or others in the community may have continued to take care of the graves.

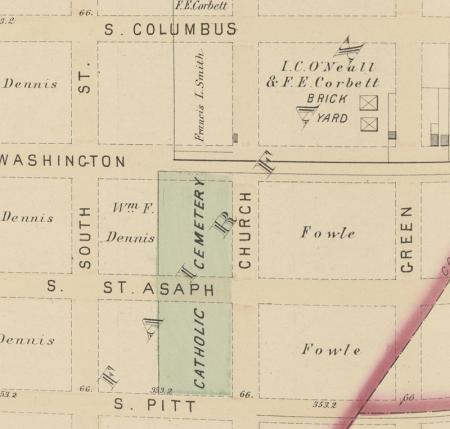

However, as the nineteenth century progressed, the wooden headboards marking burial locations decayed and disappeared. Disturbance and desecration of the graves ensued, at first affecting those on the edges of the cemetery as brick manufacturers dug into the area on the western boundary of the burial ground to mine for clay, perhaps beginning as early as 1868. Encroachment on the borders continued into the twentieth century with the construction of two major thoroughfares: the George Washington Parkway completed in 1932 along the eastern side of the property and the Washington Beltway (I-495) in 1964 immediately to the south.[ii]

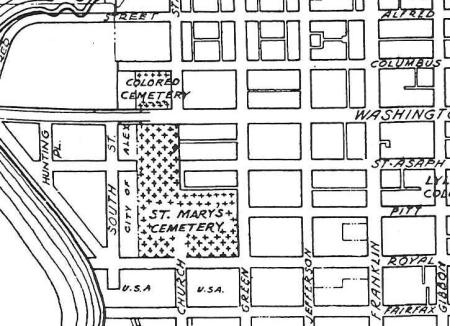

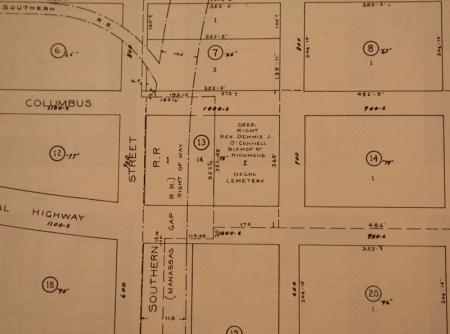

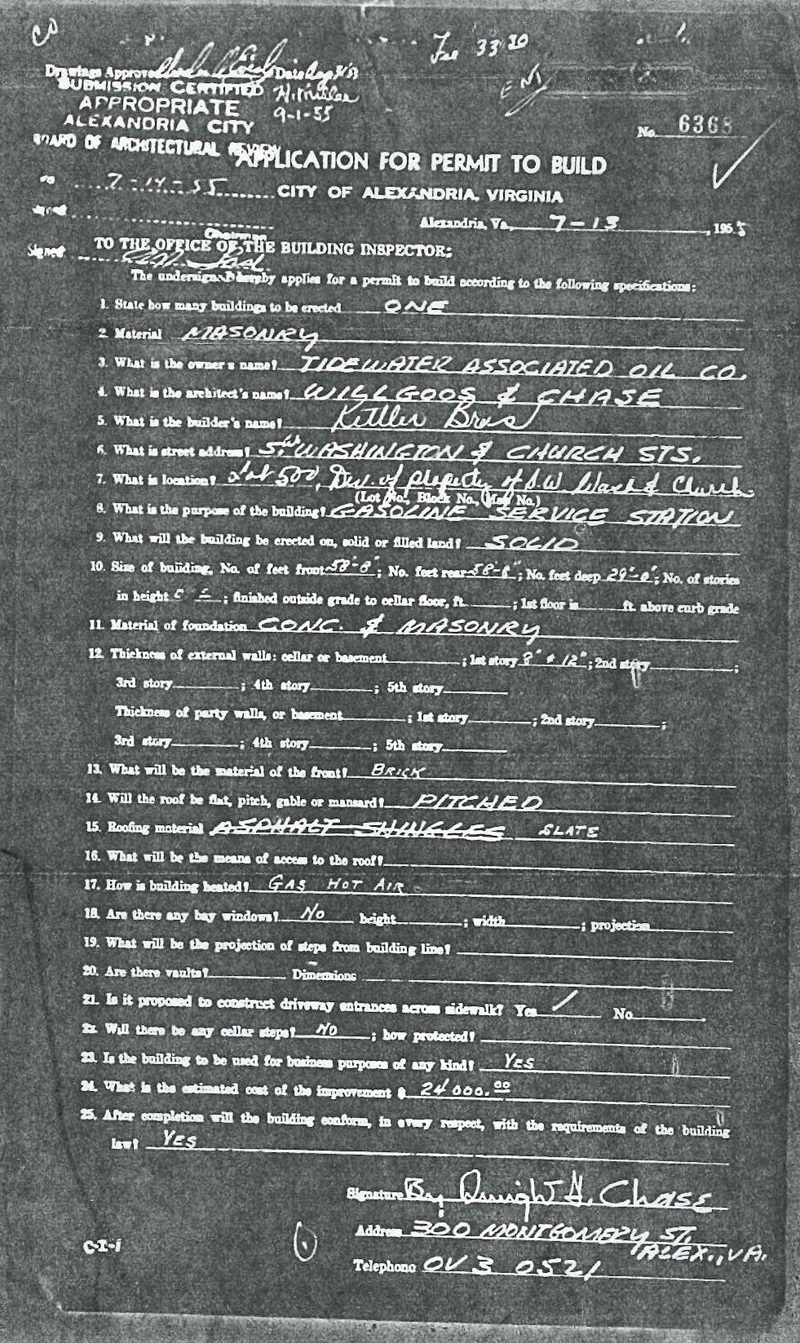

To make matters even worse, in the middle of the twentieth century, disturbance and desecration of graves took place within the boundaries of the cemetery proper. The Smith family had regained ownership of their property about a year after the war ended. They spent decades requesting monetary compensation from the federal government for the use of their property as a cemetery, even unsuccessfully offering to sell it so that it could be preserved as a burial ground, but it is unclear if they ever received any payment. Eventually, the Smiths sold the property to the Archdiocese of Richmond in 1917 for $10.00, and in 1946, the lot was rezoned for commercial use with Alexandria City Council approval over the objection of the city’s Planning Department. Interestingly, the rezoning application included a stipulation that the property could not contain a gas station.[iii] However, when the Tidewater Oil Company purchased the property for development in 1955, the Archdiocese removed the restriction, paving the way for construction of the Flying A service station, fronting on S. Washington Street.[iv] Through the years, the city approved additional permits for placement of underground gas tanks on the lot, which obviously caused even greater desecration with disturbance to and removal of numerous graves. Council also permitted construction of a second building in 1960.[v] At no time did any of the deeds indicate the presence of a burial ground on the property, although it was denoted as a “Colored Cemetery” on city maps as late as 1946.

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Source: Alexandria City Map, Office of the City Engineer, on file, Special Collections, Alexandria City Library, Alexandria, VA, 1946

Smith Family Regains Freedmen’s Cemetery Property

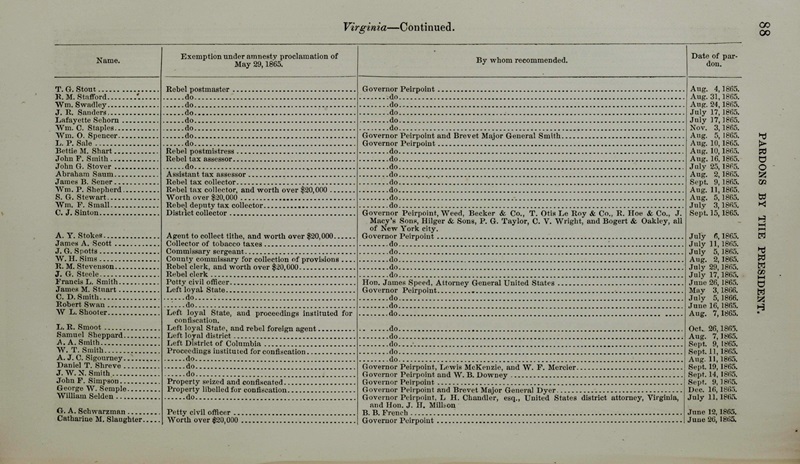

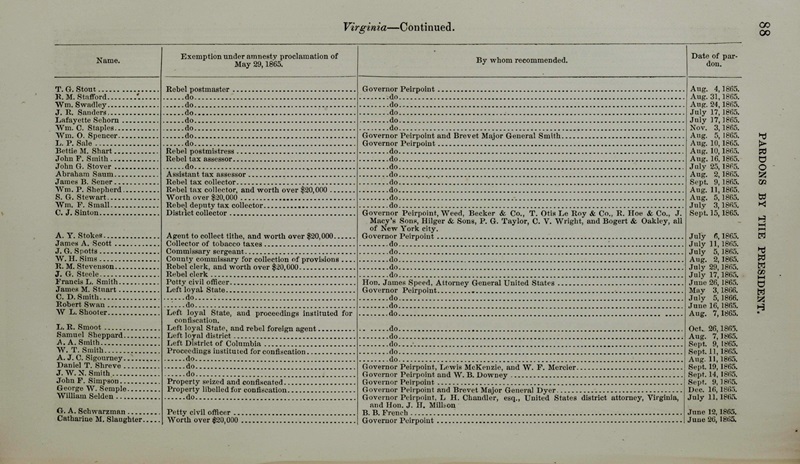

Francis L. Smith and his family returned to Alexandria at the end of the war. Probably anxious to resume normal life, Smith took an oath of allegiance as a prerequisite to receiving a pardon for his role in the Civil War from President Andrew Johnson. Johnson, a Southern Democrat with pronounced states’ rights views, had begun a process to reconstruct the former Confederate States, generally pardoning all Confederates who would take the oath, but requiring leaders and men of wealth to obtain special Presidential pardons. Smith’s pardon from Johnson became official on June 26, 1866, allowing him full rights to his Alexandria property, including the cemetery lot.[vi]

Source: Pardons by the President, H. Exec Doc 16, Serial Set Vol. No. 1330, 4 December 1867, 88.

Compensation

For more than two decades, the Smith family petitioned to receive compensation for the use of their property as a cemetery by the military government, noting that Smith had taken the oath and that they had continued to pay taxes on the lot throughout the course of the war and in succeeding years.[vii] In 1867, Smith offered to sell the land for $1,000 to the Freedmen’s Bureau, [viii] who rejected it on the grounds that the Bureau had “no authority to purchase real estate,” even though the Acting Assistant Commissioner of Freedmen had endorsed the proposal.[ix] Forwarded to the Quartermaster’s Department in Washington to determine if any soldiers’ graves remained on the site, the offer still produced no compensation or interest in the purchase. The response from Washington forcefully proclaimed that the “cemetery is exclusively used for the interment of Freedmen,… no colored soldiers are buried in this enclosure.”[x] Throughout this time, burials continued in the cemetery into January 1869 under the administration of the Freedmen’s Bureau. After Smith’s death in 1877, his son, Francis L. Smith, Jr., again wrote to the Quartermaster’s Department in Washington, still producing no apparent results.[xi]

The Smith family, however, remained undaunted in their determination to receive compensation for the use of their property. Sarah Smith, Francis, Sr.’s widow, submitted another plea in 1887 that made its way into a bill in the House Committee on War Claims. A report incorporated into the bill in February 1890 implied that because soldiers’ burials had been removed from Freedmen’s Cemetery, purchase would be unlikely, reiterating that:

there is no law, other than that providing for the establishment of National Cemeteries, which authorizes the purchase of land by the War Department, for burial purposes, without the special authority of Congress.[xii]

Nevertheless, the committee’s vote appeared to support Mrs. Smith’s claim for monetary compensation. An article in the Alexandria Gazette reported that “the House of Representatives War Claims Committee has reported favorable [sic] upon the claim of Mrs. Sarah G. Smith, widow of Francis L. Smith of this city.”[xiii] However, the bill did not make it into law until February 1892. The statute included a report from the House committee, stating:

[W]e submit that it [the claim] is one where private property has been taken without due process of law and without any compensation ever having been made to its owners—in direct contravention of law—and that it is but just and right that its value and a proper sum for its use and occupation by the United States should be paid the claimant.[xiv]

The calculated government payment to Mrs. Smith was set at $3,400. However, nine months later, the Smith family still had not received compensation, and apparently threatened disturbance to the entire cemetery, as reported in the Washington Post on October 2, 1892, perhaps as a ploy to obtain the approved payment:

The location is a beautiful one for building site, and its [sic] owned by a private citizen, who, unless the Government pays for the ground, will have the bones of the dead contrabands dug up and buried in a pit.[xv]

It is unclear if the Smiths ever received the approved amount. They never carried through on the threat to dig up all the burials, but desecration had already begun with the mining for clay on the site’s western boundary.

Freedmen’s Cemetery remained in the Smith family’s possession until April 1917 when Margaret V. Smith, the daughter of Francis and Sarah, conveyed the site to Reverend Dennis J. O’Connell, Bishop of Richmond, for the sum of $10.00.[xvi] The decision to transfer Freedmen’s Cemetery to the Archdiocese of Richmond probably stemmed from the fact that St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery was situated on the east side of S. Washington Street, directly across from the African American burial ground. It is noteworthy that the deed of sale made no mention of the cemetery on the property nor of the need for it to be cared for as a sacred place of burial.

Cemetery Maintenance and Use After 1869

With the end of federal management of Freedmen’s Cemetery in January 1869, it is likely that individuals continued to be buried on the site and that African American members of the community cared for the graves of loved ones and others who had passed away. Several historical documents hint at the continued use of the cemetery by the community. The report that accompanied the Smiths’ 1887 claim for compensation notes that “the lot in question [is] a special depository for the remains of deceased freed people, for which purpose it has been used up to the present time” [emphasis added].[xvii] Although this reference may merely indicate that the property remained a burial ground used in the past, a Washington Post article published in March 1892 echoed that burials continued in the cemetery “at the end of South Washington street and just opposite the Catholic cemetery,” noting, “[t] he Old site has been used of late as a sort of potter’s field,”[xviii] i.e. a burial place for the indigent.

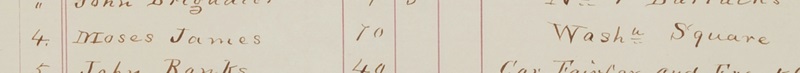

The March 1892 newspaper account also offers evidence of continued care of the graves by families of the deceased. By this time, the wooden headboards provided by the federal government to mark the graves had disintegrated. Although the military had replaced wooden markers with gravestones in Soldiers’ Cemetery in 1876, keeping alive the memory of the named individuals and the sanctity of that place, nothing of this nature had occurred in Freedmen’s Cemetery. However, some family members of those who had passed away undoubtedly took on this responsibility, placing their own stone markers. Certainly, this would have been the case for Moses James, whose name is listed on page 73 in the Book of Records,[xix] as evidenced by a description of his headstone in the March 1892 article:

It is a small marble affair and bears the inscription: ‘Moses James. Died September 4, 1865, aged seventy years.’[xx]

Source: Book of Records, p. 73, Library of Richmond, Virginia

Care of the cemetery may have also taken the form of community maintenance of mounds over the graves, a long-term practice in African American cemeteries documented into the 1930s. The mounding of earth helped to compensate for the normal settling of the soils as coffins and the remains they contained began to decompose. Perhaps more important to the community than this practical purpose, however, is the fact that the mounds themselves served as grave markers, even if stones were not present.[xxi]

While other groups also appear to have considered mound maintenance a priority, it is noteworthy that a researcher studying the connections between African and African American burial traditions noted that ideology may have played a role in this practice in African American cemeteries. It reflected the persistence of a “belief that the mound of earth above the grave was at one with the spirit within” and fostered actions to maintain the cemetery mounds as “a complex message of concern, protection, arrest, and immortality.”[xxii]

Again, the March 1892 Washington Post article may have unknowingly highlighted the on-going care of the cemetery, reporting that “many of the mounds are still pretty well preserved.”[xxiii] A 1927 aerial photograph of this section of Alexandria shows faint images of rows of burials on the property, possibly the remnants of the mounded earth over the graves. Thus, on-going maintenance of Freedmen’s Cemetery by descendent families and perhaps the African American community as a whole, at least throughout the entirety of the 19th century if not longer, seems extremely likely, given that the burial ground had become the final resting place for more than 1,700 of the city’s residents.

The memory of the site as a burial ground endured into the mid to late twentieth century for some families whose loved ones were interred there, despite the disturbances and desecration that took place. Children who played there in the mid-1950s called it “the old cemetery lot,” hearing it referred to in this manner by their elders, but never knowing it themselves as a cemetery.[xxiv] During the archaeological investigations prior to memorial development, a relative of an individual buried at the site told archaeologists working there that he had learned about the cemetery as a child.[xxv] the neglect and desecration that occurred for more than a century needs to be documented and remembered as it remains an integral part of the history of both the cemetery and the city.

Disturbance and Desecration

The neglect and desecration that occurred for more than a century remains an integral part of the history of both the cemetery and the city. While the March 1892 Washington Post article provides clues to the continuation of burials and the care of the cemetery, its main message highlights the desecration and disturbance of graves on the edges of the burial ground that resulted from the mining of clay for brick manufacturing. This encroachment may have begun as early as 1868 with a brick manufacturer’s purchase of the block north of the cemetery, and the likelihood that mining for clay may have begun to the west of the burial ground at that time or shortly thereafter.

Going forward into the twentieth century, it is difficult, if not impossible, to imagine that the City of Alexandria would have remained unaware of the presence of an African American cemetery on this property as roads encroached on its boundaries and as approvals were issued for the construction of buildings on the site. Indeed, an early twentieth-century deed has a plat showing the location of Freedmen’s Cemetery as the “Negro Burying Ground” [xxvi] and a 1937 City of Alexandria tax map demarcates the lot as a “Negro Cemetery.”[xxvii] In 1946, a map produced by the city’s engineering department denoted the location as a “Colored Cemetery”[xxviii] just nine before issuance of the first permits for construction.

Brick Manufacturing and Erosion

The 1892 Washington Post article cited “coffin ends” protruding from the “the banks like cannon from the embrasures of some great fort,” conjuring up compelling and disturbing imagery of the desecration of the graves occurring on the edges of the cemetery that resulted from clay-mining for the manufacture of bricks. The article goes on to contend:

There are many bones scattered around, and a visitor retired from the field yesterday afternoon with the shoulder-blade of some poor old black contraband who had found his last resting-place there….[xxix]

Definitive identification of Freedmen’s Cemetery as the site of this desecration comes from the article’s mention of a replacement gravestone for Moses James, known from the Book of Records to have been buried there on September 4, 1865.[xxx]

It is noteworthy that the March 1892 Washington Post article indicates that the owners of the cemetery “allowed the neighboring brick yards [plural] to dig clay from the outer edges of the graveyard.”[xxxi]Brick manufacturing on the properties adjacent to Freedmen’s Cemetery had begun as early as 1868 when Francis Smith sold property north of the site to brickmaker John Tucker. Sometime before 1875, Tucker and his partner had also become owners of a lot on the western boundary of the burial ground, and they proceeded to sell both parcels of the brickyard to F.E. Corbett and I.C. O’Neal. The use of these parcels for brickmaking possibly continued into the twentieth century with O’Neal transferring his share in the business to Charles Yohe in 1889.[xxxii] The brick manufacturing process took place on the lot to the north, while mining for clay probably occurred on the western parcel. A topographic map from the Civil War era shows that the western lot appears to have a slope down to a small gully, perhaps containing a seasonal stream flowing into Great Hunting Creek; this area may have been a source location for the clay.[xxxiii]

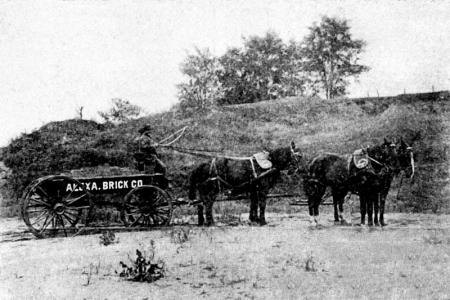

A second brick-manufacturing company appears to have begun operations south of Freedmen’s Cemetery around 1882, eventually developing into the Alexandria Brick Company. The northern embankment of the Manassas Gap Railroad cut, a ditch constructed in the 1850s but never utilized for its intended purpose, formed the southern boundary of Freedmen’s Cemetery with the southern embankment and half of the ditch owned by the Alexandria Brick Company property.[xxxiv]

Thus, both the western and the southern boundaries of Freedmen’s Cemetery may be the locations of the desecration described in March 1892. Disturbance caused by Corbett and O’Neal/Yohe’s mining for clay and erosion along the western border could have exposed coffins and bones along this natural slope. With burials oriented west to east (a Christian orientation allowing for souls to rise up when Gabriel blows his horn with the appearance of the morning sun), it is possible that brick-mining could have caused cannon-like protrusions as erosion exposed the western “head” ends of the coffins near the top of this slope. Similarly, disturbances to graves could have resulted from activities of the Alexandria Brick Company or erosion of the northern embankment of the Manassas Gap Railroad cut along the cemetery’s southern border.

Almost two years later, in January 1894, the Post again reported on desecration in a cemetery for the freedom-seekers at the south end of town. At this time, the article did not invoke disturbances caused by the clay-mining activities, instead citing only erosion during storms:

On a bluff 100 feet above the level of Hunting Creek at a place called Bromalaw,…is a graveyard containing the remains of nearly 4,000 contrabands who died…during the war. This graveyard is surrounded on the south and west by two deep washouts, which are widened by each freshet. The graves are being washed out and the skeletons float down into the Potomac. On the south and west, the bones are exposed by the washing away of the land, and it is said that they are sold to the fertilizing factories.[xxxv]

A response to the Washington Post article, published on the same day in the Alexandria Gazette, insisted that the reported desecration was not occurring in Freedmen’s Cemetery, the graveyard located “at the southern end of Washington street directly opposite the Catholic cemetery.”[xxxvi] However, a careful reading of the Post story suggests that the erosional disturbances were most likely continuing at Freedmen’s. In particular, the article cites that the erosion was occurring on the south and west sides of the graveyard, locations of the embankments where the desecration was occurring in 1892.

Source: G.M. Hopkins, City Atlas of Alexandria, VA. Philadelphia, PA: F. Bourquin’s Steam Lithographic Press, 1877

Source: “Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post, March 29, 1892

Road Construction

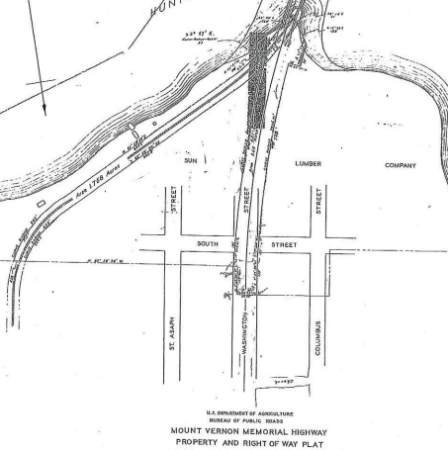

George Washington Memorial Parkway

At the time of the Civil War, the southernmost extent of Washington Street, platted on historical maps to the banks of Hunting Creek, terminated at a dead end on the west side of the Catholic Cemetery. Francis Smith’s property, the lot across the street taken for the creation of the Freedmen’s Cemetery, extended into the middle of what would have been the platted roadway. At this location, S. Washington Street was but a narrow path that did not cross Hunting Creek, perhaps stopping at the deep cut constructed in the 1850s for the Manassas Gap Railroad, a project that never fully materialized.

In 1928, Congress authorized construction of the Mount Vernon Memorial Highway, a new road connecting George Washington’s Mount Vernon to Washington, D.C., via Alexandria, a project that was expanded in 1930 to become known as the George Washington Memorial Parkway.[xxxvii] Touted as America’s Most Modern Motorway, the linking route was designed to accommodate the rapidly growing tourist and commuter traffic of the area, while preserving scenery, linking sites associated with George Washington’s life, and providing recreational opportunities along the Potomac River shoreline. As part of the road construction project, S. Washington Street was extended to the south and widened. Construction of the concrete parkway, lined with curbs, sidewalks, and gutters, began in May 1931. As the work progressed on the east side of Freedmen’s Cemetery, disturbance to graves that were present in the portions of the lot that lay in the middle of S. Washington Street became inevitable. Archaeological work conducted as part of the memorial project discovered evidence of this desecration.

Source: Mount Vernon Memorial Highway and Right of Way Plat, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Public Roads, 1930

Capital Beltway, Interstate 495 (I-495)

Construction of the 22-mile Virginia section of the Capital Beltway began in April 1958. The route of the highway through the marshlands along Hunting Creek and the Cameron Run Valley at the southern border of Alexandria presented challenges for the engineering team. The section just south of Freedmen’s Cemetery opened around the time of completion of the highway in April 1964.[xxxviii] In this vicinity the highway roughly followed the alignment of the proposed but unrealized nineteenth-century Manassas Gap Railroad along the southern boundary of the Freedmen’s Cemetery property. Deeper and wider than the railroad cut, Beltway construction impacts erased the physical evidence of the nineteenth-century feature and extended into the cemetery lot. Destruction and desecration of graves, this time on the southern boundary of Freedmen’s Cemetery, ensued, again confirmed by archaeological work. None of the plans for I-495 cited the presence of the cemetery. On the cold, wet windy day celebrating the Beltway’s opening, the speeches by federal and state officials almost certainly made no mention of the burial ground extending into the road’s right-of-way.

Source: Capital Beltway, I-495, Virginia Department of Highways, Richmond

Construction on the Cemetery Property

Construction of the George Washington Memorial Parkway on the east side of Freedmen’s Cemetery resulted in an existential threat to the preservation of the graves present on the site. This undeveloped property, formerly bordering a little-used, dead-end road, suddenly became valuable real estate. By 1946, Peter L. Ireton, the Bishop of Richmond, had begun the process of rezoning the cemetery property in anticipation of its sale and development. On June 25, despite the objections of the city’s Planning Department, Alexandria City Council rezoned the property for commercial use.[xxxix] Less than three months later, the Archdiocese sold the Freedmen’s Cemetery property to a commercial developer. The deed of sale, dated September 3, 1946, contained the following restrictions:

- Said property, nor any portion thereof, shall ever be used for an automobile service station and the definition of “automobile service station,” shall include a public garage either used for storage or automobile repair.

- The sale of alcoholic beverages, or the storage thereof for sale, is prohibited on said property, or any portion thereof.[xl]

The reason for the restrictions remains unstated. While it is tempting to speculate that they stemmed from knowledge related to the presence of the cemetery on the site, it seems more likely that the restrictions reflect a concern about activities near St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery, which was located directly across S. Washington Street; for there was never any mention of the Freedmen’s lot as a burial ground.

Source: Tax Map, 1939, City of Alexandria

The Gas Station

The property changed hands several times in the late 1940s and early ‘50s, but no development took place.[xli] Then, in 1955, the Tidewater Associated Oil Company requested and received a building permit from the city for the construction of a gas station on the eastern section of the cemetery lot. Within days of requesting the permit, Bishop Ireton revoked the restrictions he had placed on the use of the property in 1946, and the owners conveyed the property at the corner of Church and S. Washington streets to the oil company.[xlii] As was the case with previous deed transfers, the land records make no mention of the use of the site as a burial ground.

Initial construction of the gas station, first known as Harper’s Flying-A and then as Charley’s Flying-A Service, undoubtedly caused disturbance to graves within the cemetery boundaries. Excavations to place the foundations of the structures, bury utilities, and grade the surface for access ramps, etc. dug into the soils of the cemetery, cutting through and removing graves.[xliii] The greatest desecration occurred as a result of placement and replacement of large underground tanks, which would have removed the many burials that were present in the tank locations.[xliv] Desecration continued after the sale of the property to the Mobil Oil Corporation in 1967 with the expansion and renovations of the building and pump islands as well as the excavation of a new underground tank area in the years that followed.[xlv] Stories have been told that laborers involved in construction projects at the gas station saw evidence of the burials, but no written accounts have been discovered to date.

Source: Permit 7130 Oct 1959, Archives and Records Division, Office of Historic Alexandria

Church Street Building

By 1959, Charles F. Gerber owned the western section of the cemetery property and received a permit from the city to construct a two-story building on the lot at 714 Church Street.[xlvi] Initially serving as the location for Gerber’s masonry shop with rental apartments on the second floor, the structure eventually became an office building and local headquarters for Domino’s Pizza, Inc. Disturbance and desecration of graves would have resulted from construction of the original building in 1960 with its foundation set below grade, from building a rear addition in 1965,[xlvii] from leveling the ground for the creation of a parking lot, and from development of driveways and ramps for access to the property.

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

Footnotes

[i] “Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post, 29 March 1892.

[ii] Classified Central Files, 1912-1950, 420 Right of Way, General Properties, Mount Vernon Virginia, 1928-1942; Bureau of Public Roads, Record Group 30, Box 1385, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Scott Kozell, Capital Beltway History, http://www.capital-beltway.com/Capital-Beltway-History.html.

[iii] Alexandria Land Records Liber 233, Folio 104, Alexandria Courthouse, Alexandria, VA; Alexandria City Council Minutes, 25 July 1946, Alexandria Library microfilm reel-00473, page 479, Alexandria, VA.

[iv] Alexandria Building Permit #6368, 13 July 1955, City Archives, Alexandria, VA; Alexandria Deed Book 416:460, 29 July 1955, Alexandria Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA.

[v] Alexandria Building Permit #7130, 25 November 1959, City Archives, Alexandria, VA.

[vi] Pardons by the President, H. Exec Doc 16, Serial Set Vol. No. 1330, 4 December 1867, 88; Samuel P. Lee, Superintendent; Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, 7 May 1866, Records for the Assistant Commissioner for the District of Columbia, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, 1865-1869, Microfilm M-1055, Reel #6, Freedmen Bureau Paper, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Smith later publicly acknowledged his allegiance to the Union by inviting members of the U.S. House of Representatives to Alexandria in 1876 to celebrate the new national holiday honoring Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, “From Washington,” Alexandria Gazette, 21 February 1876, 3.

[vii] Cited in U.S. Congress, House, Committee of the War Claims, Sarah G. Smith, 5 February 1892, 52nd Cong., 1st sess., H. Rept. 110, to accompany H.R. 3561.

[viii] Francis L. Smith to Colonel S.P. Lee, Assistant Superintendent of the Freedmen’s Bureau, 13 April 1867, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 225, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[ix] Cited in U.S. Congress, House, Committee of the War Claims, Sarah G. Smith, 5 February 1892, 52nd Cong., 1st sess., H. Rept. 110, to accompany H.R. 3561.

[x] Cited in U.S. Congress, House, Committee of the War Claims, Sarah G. Smith, 5 February 1892, 52nd Cong., 1st sess., H. Rept. 110, to accompany H.R. 3561.

[xi] Francis L. Smith, Jr. to Quartermaster General, Washington, D.C., 12 October 1877, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 225, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xii] Samuel B. Holabird, Quartermaster General, “First Enclosure for House Committee on War Claims, H.R. 1131, Bill for the Relief of Sarah G. Smith, extx. of Francis L. Smith, Quartermaster General’s Office” Washington, D.C., 31 January 1890.

[xiii] Alexandria Gazette, 26 February 1890

[xiv] U.S. Congress, House, Committee of the War Claims, Sarah G. Smith, 5 February 1892, 52nd Cong., 1st sess., H. Rept. 110, to accompany H.R. 3561.

[xv] “Alexandria News In Brief,” Washington Post, 2 October 1892, 5.

[xvi] Alexandria Deed Book 66:132, 25 April 1917, Alexandra Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA.

[xvii] U.S. Congress, House, Committee of the War Claims, Sarah G. Smith, 5 February 1892, 52nd Cong., 1st sess., H. Rept. 110, to accompany H.R. 3561.

[xviii] “Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post, 29 March 1892.

[xix] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 73.

[xx] “Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post, 29 March 1892.

[xxi] Gregory D. Jeane, “The Upland South Folk Cemetery Complex: Some Suggestions of Origin,” in Richard E. Meyer, ed., Cemeteries & Gravemarkers: Voices of American Culture, (Utah State University Press, Logan, Utah, 1992, 107-136; Christoper N. Matthews and Eric L. Larsen, “White Privilege and Silencing within the Heritage Landscape: Race and the Practice of Cultural Resource Management,” in Jodi Barnes, ed., The Materiality of Freedom, Archaeologies of Post-Emancipation Life, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2011), 34.

[xxii] Robert Farris Thompson, “Kongo Influences on African American Artistic Culture,” in Joseph P. Holloway, ed., Africanisms in American Culture, (Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 1990), 171, 173.

[xxiii] “Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post, 29 March 1892.

[xxiv] T. Michael Miller, Memorandum to Pamela Cressey, 1 April 1997, copy archived at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xxv] Eric Larsen, Freedmen’s Cemetery Excavation Field Notes, 2007, on file Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xxvi] Alexandria Deed Book 65:589, 26 December 1916, Alexandria Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA.

[xxvii] Alexandria Land Use Map, Real Property Survey, May 1939, Vol. II, Plate 126, City of Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xxviii] Alexandria City Map, Office of the City Engineer, on file, Special Collections, Alexandria City Library, Alexandria, VA, 1946.

[xxix] “Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post, 29 March 1892.

[xxx] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 73.

[xxxi] “Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post, 5 January 1894.

[xxxii] Fairfax County Deed Books, H4:531, S4:194-5, I5:129, Fairfax County Circuit Court Historic Records, Fairfax, Virginia, cited in David J. Soldo and Martha R. Williams, -Phase I Archival and Archeological Investigations at the Gunston Hall Apartments, Alexandria, Virginia, R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc., Frederick, Maryland, 2005, 17.

[xxxiii] J. G. Barnard, Bvt. Major Gnl, Map of the Environs of Washington. 1862, Library of Congress. Geography and Maps Division, Washington, D. C.

[xxxiv] Fairfax County Deed Books, B5:491, 17:690, Fairfax County Circuit Court Historic Records, Fairfax, Virginia.

[xxxv] “Alexandria Affairs,” Washington Post, 5 January 1894, 6.

[xxxvi] Alexandria Gazette, 5 January 1894.

[xxxvii] Classified Central Files, 1912-1950, 420 Right of Way, General Properties, Mount Vernon Virginia, 1928-1942. Bureau of Public Roads, National Archives, College Park, Record Group 30, Box 1385.

[xxxviii] Scott Kozell, Capital Beltway History, http://www.capital-beltway.com/Capital-Beltway-History.html.

[xxxix] Alexandria City Council Minutes, 25 June 1946, Alexandria Library Microfilm Reel-00473, 479; “Council Compacts: Rezoning Approved,” Alexandria Gazette, 26 June 1946.

[xl] Alexandria Deed Book 233:104, 2 September 1946, Alexandria Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA.

[xli] Alexandria Deed Book 233:105, 2 September 1946, Alexandria Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA; Alexandria Deed Book 335:455, 24 March 1952, Alexandria Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA.

[xlii] Alexandria Building Permit #6368, 13 July 1955, City Archives, Alexandria, VA; Alexandria Deed Book 416: 460, 462, 29 July 1955, Alexandria Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA.

[xliii] Alexandria Building Permits #3658, 28 July 1965; #2749, 6 January 1970; #4369, 7 January 1970; #9525, 30 June 1975; #6280, 13 August 1985; #5355, 27 September 1985; City Archives, Alexandria, VA.

[xliv] Alexandria Building Permits #2253, 6 April 1965; #2576, 11 January 1968; #2734, 8 October 1969; #2834, 4 December 1970; #5355 27 September 1985; City Archives, Alexandria, VA.

[xlv] Alexandria Deed Book 666:493, 28 April 1967, Alexandria Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA; Alexandria Building Permits #2749, 6 January 1970, #9525, 30 June 1975, #5355, 27 September 1985, City Archives, Alexandria, VA.

[xlvi] Alexandria Building Permit #7130, 25 November 1959, City Archives, Alexandria, VA.

[xlvii] Alexandria Building Permit #22341, 16 September 1965, City Archives, Alexandria, VA.