Cemetery: Civil Rights Activism and USCT Burials

Civil Rights Activism and USCT Burials

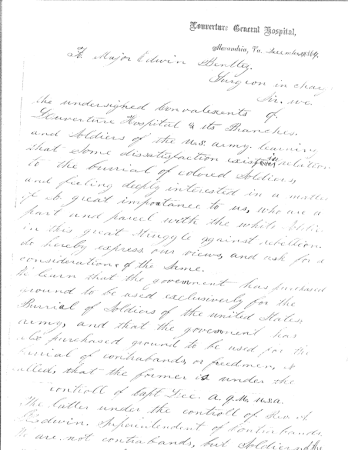

As American citizens, we have a right to fight for the protection of her flag, that right is granted, and we are now sharing equally the dangers and hardships in this mighty contest, and should shair the same privileges and rights of burial in every way with our fellow soldiers, who only differ from us in color.[i]

USCT Petition for Burial in Soldiers’ Cemetery, 27 December 1864

Source: Records of the Quartermaster General of the United States, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

The account of the burial of United States Colored Troops (USCT) in Freedmen’s Cemetery and their subsequent removal from Freedmen’s with reinterment in Soldiers’ Cemetery (now Alexandria National Cemetery) stands as a strong reminder of the legacy of human rights activism that began with aspirations for self-emancipation, self-preservation, and self-determination of the formerly enslaved population of the United States and continues to the present. The story begins with the gradual acceptance on the part of President Abraham Lincoln to allow Black men to serve as a much-needed fighting force for the cause of freedom and the explicit authorization in the Emancipation Proclamation (January 1, 1863) for the enlistment of African American soldiers. More than 200,000 in number, the troops courageously played a huge role in some of the most hard-fought battles of the Civil War, including those near Richmond and Petersburg. Wounded and sick soldiers, especially from these clashes in the Virginia theater, often found themselves undergoing treatment in Alexandria’s hospitals, where battle injuries and, more often, diseases took their toll.

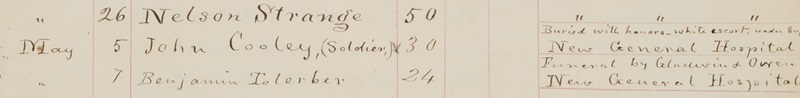

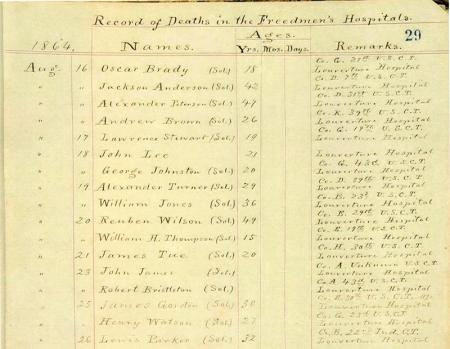

With enlistment of African American men beginning in the early months of 1863,[ii] it might be expected that Black soldiers who passed away in Alexandria would have always been laid to rest in Soldiers’ Cemetery, officially established in 1862 as one of the earliest Civil War burial grounds created after the July passage of the act authorizing the formation of the national cemetery system.[iii] However, this does not appear to have been the case. When Private John Cooley passed away in the city in May 1864, both Reverend Gladwin and Julia Wilbur cited him as the first African American soldier to die in Alexandria, although it is perhaps possible that they may not have been aware of previous deaths of USCT in the city. In his role as Superintendent of Contrabands, Gladwin shepherded Cooley’s body for burial to Freedmen’s Cemetery and began interments of African American soldiers in the burial ground under his jurisdiction. While he apparently did discuss this decision with a doctor at L’Ouverture Hospital, he did not seek confirmation from the Alexandria Quartermaster’s Department, which oversaw the interment of soldiers in the national cemetery.

It was not until December 1864 that the burial of African American soldiers at Freedmen’s came to the full attention of the staff of the Army Quartermaster in Alexandria. A controversy over the burial location for the USCT who passed away in the city surfaced at that time and came to a head when Gladwin ordered a forceable diversion of a funeral procession bound for Soldiers’ to Freedmen’s Cemetery. The disagreement, perhaps partially reflecting a bureaucratic power struggle but obviously with strong racial undertones, arose between Gladwin, who wanted to maintain oversight of the burials of African American soldiers in Freedmen’s Cemetery, and Captain James G.C. Lee, Assistant Depot Quartermaster in Alexandria in charge of military burials, who believed that they should be interred in Soldiers’ Cemetery.

Gladwin’s diversion caused considerable consternation among the African American soldiers undergoing treatment at L’Ouverture Hospital. More than four hundred signed a petition articulating that Black soldiers who made the ultimate sacrifice and lost their lives for their country deserved burial in the national military cemetery, where their courage and service would be acknowledged and remembered.[iv] With the support of Captain Lee, who pronounced the request as “just and right,”[v] the protest and petition proved to be one of the earliest known successful civil rights actions in Alexandria. It not only resulted in an explicit policy to bury USCT at the military cemetery, but also called for soldiers (118 in number) to be exhumed from the civilian burial ground and reinterred at Soldiers’ Cemetery.[vi

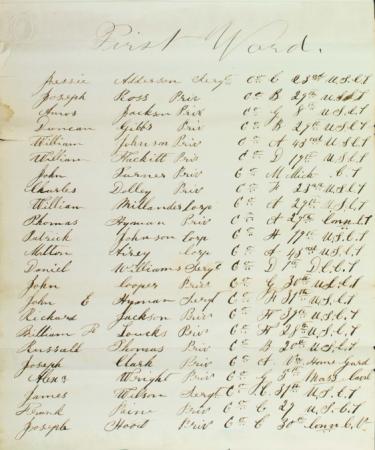

Source: Book of Records, p.25, Library of Virginia, Richmond

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria

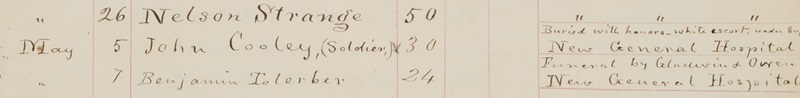

USCT Burials at Freedmen’s Cemetery, May Through December 1864

Source: Book of Records, p. 29, Library of Virginia, Richmond

A few months after Freedmen’s Cemetery opened, Gladwin initiated the process of interment of USCT in a separate section of the burial ground.[vii] The first African American soldier buried there was Private John Cooley, a soldier of the 27th USCT. Cooley, born into enslavement in Charlottesville, Virginia, died at the age of 23 in L’Ouverture Hospital of a remittent fever on May 5, 1864.[viii] Julia Wilbur attended Cooley’s funeral, remarking on Gladwin’s failure to recognize the sacrifices made by the soldiers during the devastating conflict embroiling the nation:

Between 4 & 5 P.M. went to Funeral of a Colored Soldier, the first one who has died here. Had a white escort & was buried in the New Freedmen’s B. Ground. Mr. Gladwin officiated. He made no allusion to the particular circumstances of the Country, not a word of encouragement to its brave defenders. He shows no sympathy for the people, nor for the Country.[ix]

Between May and December of 1864, records document that 118 Black soldiers were buried in Freedmen’s Cemetery under the direction of Superintendent Gladwin.[x] The majority, like Private Cooley, had succumbed to various illnesses and injuries while being treated in L’Ouverture Hospital.[xi]

Divergent Views - Reverend Gladwin and Captain Lee

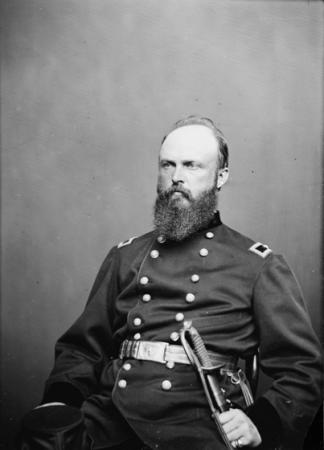

Source: Matthew Brady, National Archives

In December 1864 Reverend Gladwin apparently learned that Captain J.G.C. Lee, whose duties as Assistant Depot Quartermaster included management of burials at Soldiers’ Cemetery, was planning to order that the burial of the USCT who died in Alexandria take place in the Soldiers’ Cemetery. Lee’s planned directive stemmed from what he deemed the military’s “desire to have all soldiers in one place,” as he had been previously required to disinter soldiers’ burials made on private property and rebury them in Soldiers’ Cemetery.[xii] Although Gladwin had no official jurisdiction over the burial of soldiers, he had apparently previously discussed the matter with Dr. Bentley, the Surgeon-in-Charge at L’Ouverture Hospital, who had agreed that the USCT who gave their lives for their country should be laid to rest in Freedmen’s Cemetery, established for the civilian freedom-seekers in Alexandria. In what appears to have been an attempt to preempt Lee’s changing the location for the burial of African American soldiers, Gladwin wrote to General Slough, the Military Governor, to voice his dissatisfaction with the plans of the Quartermaster’s Department:

I am informed that the question has been raised by the Quartermaster J.G.C. Lee, as to the authority and propriety of the burial of colored soldiers in the Freedmen’s Cemetery… and that it is contemplated to remove those already buried there.[xiii]

Gladwin reported that he had set aside a separate area for the burial of soldiers in Freedmen’s Cemetery and that he considered the location the “most accessible of any in the city,” able to be “beautified in any manner in which friends of patriots may desire.” He went on to “beg leave to request that there be no move made” that would entail either the removal and reburial of the soldiers at Freedmen’s or a change in the location for future interments.[xiv] Gladwin’s request resulted in the desired effect. Two days after receiving the letter, Slough’s office issued an order:

that hereafter all deceased Cold. Soldiers of this District shall be interred in the Colored Burying ground, dedicated for that purpose, which is controlled by Rev. A. Gladwin, Sup’t of Contrabands in this City.[xv]

Despite the fact that Gladwin had named Lee in the letter to Slough, it is noteworthy that Lee never officially received a copy of this order, recounting, “I continued my duties, without conferring with Gen. Slough on the subject.”[xvi] In fact, in keeping with Lee’s directive, four African American soldiers listed in the Book of Records were buried in Soldiers’ Cemetery on December 22 and 23, 1864: Caleb Mason of Baltimore (Co. B, 39th USCT, drafted June 1864), Samuel Wilson of Chillicothe, Ohio (Co. C, 27th USCT, enlisted August 1864), Samuel Brace (Co. C, 19th USCT, enrolled in Baltimore, 1863) and James Getson (or Getson James, 5th Massachusetts Cavalry). Mason and Wilson had passed away at the Baptist Church branch of L’Ouverture while Brace and Getson died at the Grace Church branch.[xvii]

The Incident

After becoming cognizant that Lee had begun implementing the directive to bury the USCT at Soldiers’ Cemetery, and with Slough’s orders in his possession, Gladwin took matters into his own hands. On December 27, the reverend redirected a funeral procession for two African American soldiers en route from L’Ouverture Hospital to Soldiers’ Cemetery, insisting instead that the burials take place at Freedmen’s Cemetery.

Ever vigilant about injustice and controversy, Julia Wilbur recorded the events in her personal diary, where she reported that

This P.M. two colored soldiers were to be buried. & Mr. G. said if they went to the Mil. B. Ground he would have the escort arrested. The bodies went to the Colored Cemetery without an escort. & Mr. G. thinks he has triumphed. The soldiers are furious. & there is danger of a fight. Mr. G. has sent a one-armed sergt. to the Slave Pen.[xviii]

As described by Captain Lee in a letter to his superiors:

Mr. Gladwin and a part of soldiers arrested my driver, took him from my hearse and drove it where they pleased, the escort returning to the hospital. As might be expected, the most intense feeling on the part of the officers was felt, that this man, a citizen, should be allowed to interfere.[xix]

Based on death dates noted in the Book of Records and Civil War pension records, the funeral procession intercepted by Gladwin would have been for Frank Wade (Co. K, 27th USCT) of Memphis, Tennessee, and/or Shadrack Murphy (Co. B, 23rd USCT) of South Carolina, both of whom died in L’Ouverture Hospital on Christmas day, 1864. They were the last members of the USCT to be buried at Freedmen Cemetery and the final entries of soldiers listed in the Book of Records.[xx]

Source: Funeral March, Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division, Washington, D.C.

The Protest and Petition

Records of the Quartermaster General of the United States, Record Group 92, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Despite their medical conditions, the “furious” soldiers undergoing treatment at L’Ouverture and its branches did not take the injustice lying down. An understanding of the reasons for this anger and resentment derives from knowledge of the evolution in the way that the U.S. military had developed a protocol for honoring those who had lost their lives in service to their country. In the early years of federal control, burials of soldiers who died in Alexandria took place at “New” Penny Hill, where the freedom-seekers were also laid to rest until the establishment of Freedmen’s Cemetery. A newspaper account indicated that 197 soldiers had been interred there, probably in the early months of 1862. The establishment of Soldiers’ Cemetery in the middle of that year created the backdrop for developing a system to honor the military dead, with 794 men interred in rows in the national cemetery by the end of the year.[xxi] Thus, the burial circumstances for white soldiers went from being placed in Penny Hill, many in unmarked graves that were scattered among previous burials, as described by Julia Wilbur,[xxii] to being organized in neat rows in a cemetery created to honor their service. By December 14, 1862, the military seems to have perfected a graveside ceremony to show honor and respect for the fallen in the recently created national cemetery, as evidenced by Wilbur’s diary entry on that date:

The drum made solemn music. The man’s name was Burrows [Burroughs] of the 14th N.Y.— The “Shining Shore” was sung. Mr. W. prayed. It was an impressive scene. Three volleys were fired over t]he grave, by 8 men. & the soldiers turned away from the 18 open graves which are ready for their occupants. How many have been filled to day I know not. They are on the 7th row of about 100 each….All the while this was going on, hundreds of men were standing on the brow of the hill at the Con. Camp, & looking at the proceedings.[xxiii].

This entry reflects a sharp contrast with her later description of the funeral of Private John Cooley on May 5, 1864, the first USCT soldier buried in Freedmen’s Cemetery, where Gladwin apparently “made no allusion to the particular circumstances of the Country, not a word of encouragement to its brave defenders.”[xxiv].

Against this backdrop, the reaction to Gladwin’s redirection of the funeral procession and arrest of the soldier driving the hearse was swift, convincing, and eloquent. The voices of the African American soldiers undergoing treatment in Alexandria’s hospitals rang out against the injustice. They prepared a petition requesting USCT burial in Soldiers’ Cemetery:

We are not contrabands, but soldiers of the U.S. Army, we have cheerfully left the comforts of home, and entered into the field of conflict, fighting side by side with the white soldiers, to crush out this God insulting, Hell deserving rebellion….To crush this rebellion, and establish civil, religious, & political freedom for our children, is the hight [sic] of our ambition. To this end we suffer, for this we fight, yea and mingle our blood with yours, to wash away a stain so black, and destroy a Plot so destructive to the interest and Prosperity of this nation, as soldiers in the U.S. Army. We ask that our bodies may find a resting place in the ground designated for the burial of the brave defenders, of our countries [sic] flag.[xxv]

The names of 443 convalescing African American soldiers followed the lofty words of the entreaty.[xxvi] These signers of the petition initiated what would become one of the earliest successful civil rights actions in the city, and perhaps in the nation.

The Resolution: “Just and Right”

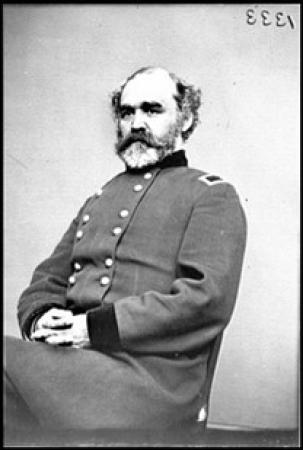

Source: Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The decision over the burial location of the USCT fell to Major General Montgomery C. Meigs, Quartermaster General for the Union Army. At that time, the Quartermaster’s Department had jurisdiction over the management of soldiers’ burials and administration of the national military cemeteries. On December 27, Captain Lee wrote to the general, providing details about the events in Alexandria and explaining that the “contraband burying ground …is not owned by the U.S., is not fenced [meaning around the soldiers’ section], as I learn, nor is it taken care of, as the regular cemetery is.”[xxvii] Lee countered the concerns of Slough and Gladwin about how to deal with African American soldiers already buried at Freedmen’s Cemetery, noting “these could be removed very easily and without additional expense by the men who take care of the military cemetery.” The correspondence included the petition from the USCT hospitalized in Alexandria and ended with Lee’s own ethical pronouncement on the burial issue:

The feeling on the part of the colored soldiers is unanimous to be placed in the military cemetery and it seems but just and right that they should be….[xxviii]

The response to Lee came just one day later, an order “that all soldiers dying in the Hospital at Alexandria will be interred in the Military Cemetery at that place until the ground is filled. After that, arrangements should be made to inter them at the National Military Cemetery at Arlington.”[xxix] A second order, issued on or about January 5, 1865, formally resolved the reburial issue, stating “that the disinterment and removal, of the bodies of Colored Soldiers from the Freedman’s [sic] Cemetery, to the U.S. Military Cemetery will commence tomorrow A.M.”[xxx] The controversy ended with the removal of Reverend Gladwin as the Superintendent of Contrabands in mid-January and his replacement by Captain James Ferree, who took on responsibility of Freedmen’s Cemetery where interment of African American civilians continued.[xxxi]

Disinterment and Reburial

Between January 6 and 21, 1865, the remains of 118 USCT were disinterred from Freedmen’s Cemetery and reburied in what is now Section B of Alexandria National Cemetery under the direction of Captain James G.C. Lee. The first soldiers moved from Freedmen’s to Soldiers’ Cemetery were James Brown of Queen Anne’s County, Maryland, and Solomon Dorsey of Baltimore, Maryland.[xxxii] Private Brown, born into enslavement and conscripted in Baltimore on May 28, 1864, died of consumption at the age of 47. Dorsey enlisted as a private in Baltimore in March 1864, likely participating in the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. He died at the age of 30 of “ascites,” an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the abdomen. They and the others removed from Freedmen’s rest today with more than a hundred additional African American soldiers recognized for their service in the “handsomely improved and adorned” national cemetery.[xxxiii] In 1876, the deteriorating wooden markers at what is now known as Alexandria National Cemetery were replaced with stone, ensuring a more secure place in history for the reinterred African American soldiers who died in Alexandria.[xxxiv] In accordance with established procedures, the dates recorded in military records for the reinterred soldiers reflect the day of burial in Soldiers’ Cemetery rather than the dates of death.[xxxv]

Footnotes

[i] U.S. Colored Troops to Major Edwin Bentley, Surgeon in Charge, at L’Ouverture General Hospital, Alexandria VA, 27 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C

[ii] Alexandria Gazette, 28 March 1863.

[iii] An Act to define the Pay and Emoluments of certain Officers of the Army, and for other Purposes. Sec. 18, 37th Congress, Session II, Ch. 200, 17 July 1862.

[iv] U.S. Colored Troops to Major Edwin Bentley, Surgeon in Charge at L’Ouverture General Hospital, Alexandria VA, 27 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[v] J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, to Major General M.C. Meigs, Depot Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[vi] Berry L. Bard, Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, to J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Roll #49, M745, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Rollin C. Gale, by command of General John P. Slough, to Reverend Albert Gladwin, Letters Sent August 1864 to June 1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2040, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[vii] Reverend Albert Gladwin letter to General John P. Slough, 16 December 1864, Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2053, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[viii] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 24; Reverend Albert Gladwin letter to General John P. Slough, 16 December 1864, Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2053, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[ix] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, Pocket Diary, 5 May 1864, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

[x] Edward A. Miller, Jr., “Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in Alexandria National Cemetery, Part I,” Historic Alexandria Quarterly (Alexandria, VA: City of Alexandria, Fall 1998), 9; Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 25-33.

[xi] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 33.

[xii] Lee to Meigs J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, to Major General M.C. Meigs, Depot Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xiii] Reverend Albert Gladwin letter to General John P. Slough, 16 December 1864, Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2053, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xiv] Reverend Albert Gladwin letter to General John P. Slough, 16 December 1864, Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xv] Rollin C. Gale, by command of General John P. Slough, 18 December 1864, Special Order 162, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2056, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xvi] J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, to Major General M.C. Meigs, Depot Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xvii] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 33; The Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, African American Soldiers of the Civil War Buried in Section B of Alexandria National Cemetery, 1864-1865, April 29, 2007; Edward A. Miller, Jr., “Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in Alexandria National Cemetery, Part II,” Historic Alexandria Quarterly (Alexandria, VA: City of Alexandria, Winter 1998).

[xviii] Edward A. Miller, Jr., “Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in Alexandria National Cemetery, Part I,” Historic Alexandria Quarterly (Alexandria, VA: City of Alexandria, Fall 1998) 9; Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 26 and 27 December 1864, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf

[xix] J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, to Major General M.C. Meigs, Depot Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xx] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 33.

[xxi] Alexandria Gazette, 29 December 1862.

[xxii] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 16 November 1862, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf

[xxiii] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 14 December 1862, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf

[xxiv] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, Pocket Diary, 5 May 1864, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

[xxv] U.S. Colored Troops to Major Edwin Bentley, Surgeon in Charge, at L’Ouverture General Hospital, Alexandria VA, 27 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C

[xxvi] U.S. Colored Troops to Major Edwin Bentley, Surgeon in Charge, at L’Ouverture General Hospital, Alexandria VA, 27 December 1864. Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C

[xxvii] J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, to Major General M.C. Meigs, Depot Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxviii] J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, to Major General M.C. Meigs, Depot Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 576, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxix] Berry L. Bard, Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, to J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Roll #49, M745, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxx] Rollin C. Gale, by command of General John P. Slough, to Reverend Albert Gladwin, Letters Sent August 1864 to June 1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2040, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxi] Reports of Chaplains, Civil War, James I. Ferree, 13 January 1865, Relieved of duty at Lincoln Genl Hosp, Report to Commanding Gen Dept Wash for assignment as Supt of Contrabands at Alexa in place of Gladwin, Record Group 94, Entry 679, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxii] “Freedmen’s Burial Ground,” Records of the Quartermaster General, Record Group 92, Entry 225, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxiii] J.G.C. Lee, Assistant Quartermaster, to Major General M.C. Meigs, Depot Quartermaster’s Office, Alexandria, VA, 28 December 1864, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, Record Group 92, Entry 57, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxiv] Alexandria National Cemetery, National Register Nomination Form, on file at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, Sec. 7, p.1.

[xxxv] Edward A. Miller, Jr., “Volunteers for Freedom: Black Civil War Soldiers in Alexandria National Cemetery, Part II,” Historic Alexandria Quarterly (Alexandria, VA: City of Alexandria, Winter 1998), 4.