Cemetery: Establishing the Cemetery

Cemetery: Establishing the Cemetery

[W]ith verbal orders from your Head Quarters [sic], …I selected and laid out the grounds for the present Cemetery in February last, and reported back; and on the 29th day of the same, received a written order to superintend the building of a fence to enclose it, and that on the 7th day of March, I commenced to inter bodies there.[i]

Reverend Albert Gladwin to John P. Slough, Letter, 16 December 1864

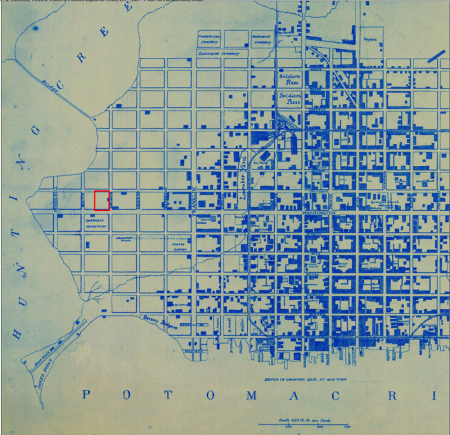

Source: "Plan of Alexandria" 1864, Office of Coast Survey Historical Map & Chart Collection, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, NOAA File Name: 32-1-1864 http://historicalcharts.noaa.gov

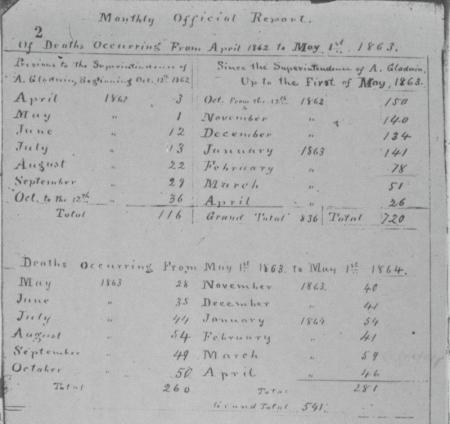

The military government in Alexandria found itself responsible not only for the welfare of the freedom-seekers, but also for the disposition of the remains of the deceased. Historical records provide insight into the challenges pertaining to burial needs posed by the arrival of so many self-emancipators. The journey to freedom left many exhausted, sick, and malnourished, in “circumstances [that] proved fatal in a very large number of cases.”[ii] Living in close quarters, reportedly “in the rudest kind of shanties, under trees and ragged canvas coverings, many times without food, necessary clothing or beds,”[iii] undoubtedly contributed to the numerous severe outbreaks of smallpox and typhoid during the war years. While exact counts would have been hard to come by due to the turmoil of the war years, a December 1862 Alexandria Gazette article documented that “one hundred and eighty-five negroes—‘contrabands’—have been buried in this place by the U.S. authorities since September 28th.”[iv] In April 1863, the Freedman’s Relief Society reported that since the start of the war two years earlier “about 800 have died” in Alexandria.[v] A tally prepared by the Superintendent of Contrabands’ office indicates that more than 1,200 African American individuals died in the City from April 1862 through February 1864 prior to the establishment of the Freedmen’s Cemetery.[vi] Clearly, the numbers kept rising.

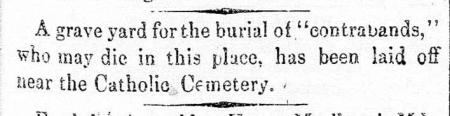

Unprepared for the magnitude of the task, the military government was perhaps not as quick to respond to the need for a suitable burial ground as would have been hoped. Prior to the establishment of Freedmen’s Cemetery, most burials of freedom-seekers, other than smallpox victims, probably took place in Penny Hill Cemetery, a public burial ground established in 1796 on Payne Street. Witnessing the crowded conditions in this burial ground, aid worker Julia Wilbur dubbed it a “heathenish place.”[vii] It was not until March of 1864, nearly three years after the beginning of federal control, that a cemetery for the “contrabands who may die in this place”[viii] was set aside on land confiscated from Confederate sympathizer Francis L. Smith.

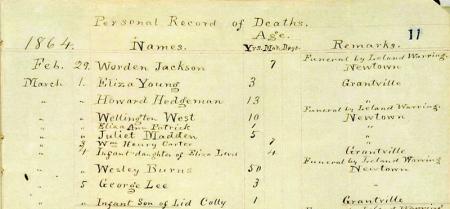

What would eventually become known as Freedmen’s Cemetery was managed during the war by the Quartermaster’s Department of the U.S. Army and then by the Freedmen’s Bureau from July 1865 into January 1869. By this time, the 1.5 acre of land situated at the corner of S. Washington and Church streets on the southern outskirts of the developed part of the city had become the final resting place for at least 1,711 individuals. Based on documentation that burials began on March 7, 1864, researchers have postulated that the first to be put to rest at Freedmen’s Cemetery could have been three-year old George Lee, who lived in Newtown, and the infant son of Lid Colly from Grantville, both of whom died on Saturday, March 5, two days before the cemetery opening.[ix]

Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 2.

Source: Alexandria Gazette, March 4, 1864

Source: Book of Records,, page 11, Library of Virginia, Richmond

Burial Places Prior to the Establishment of Freedmen’s Cemetery

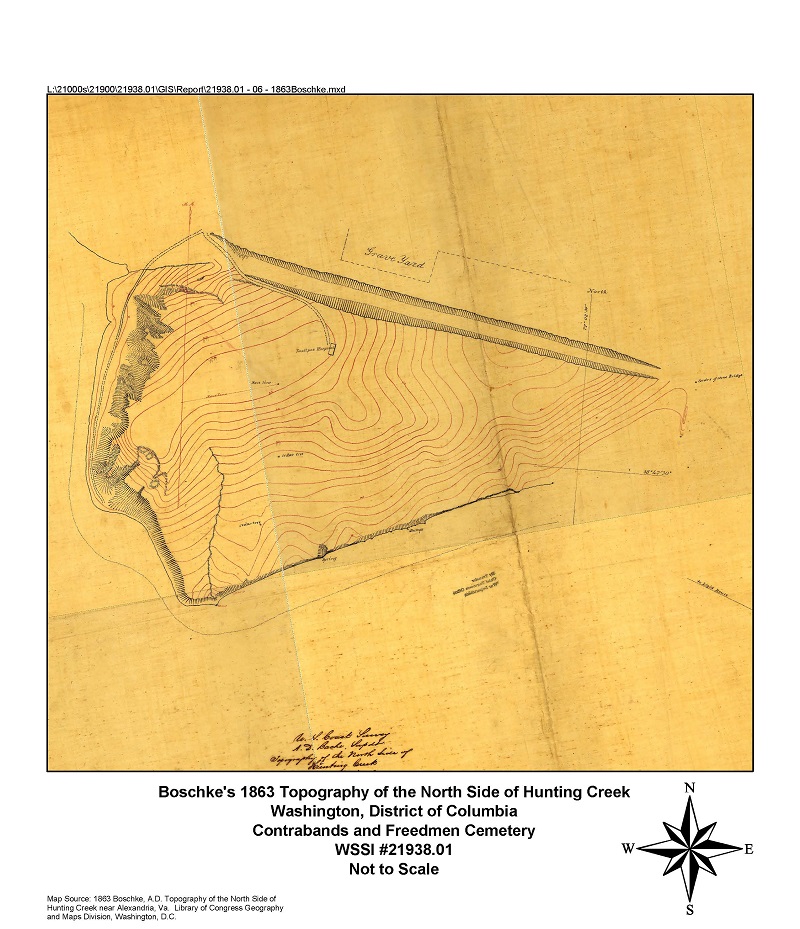

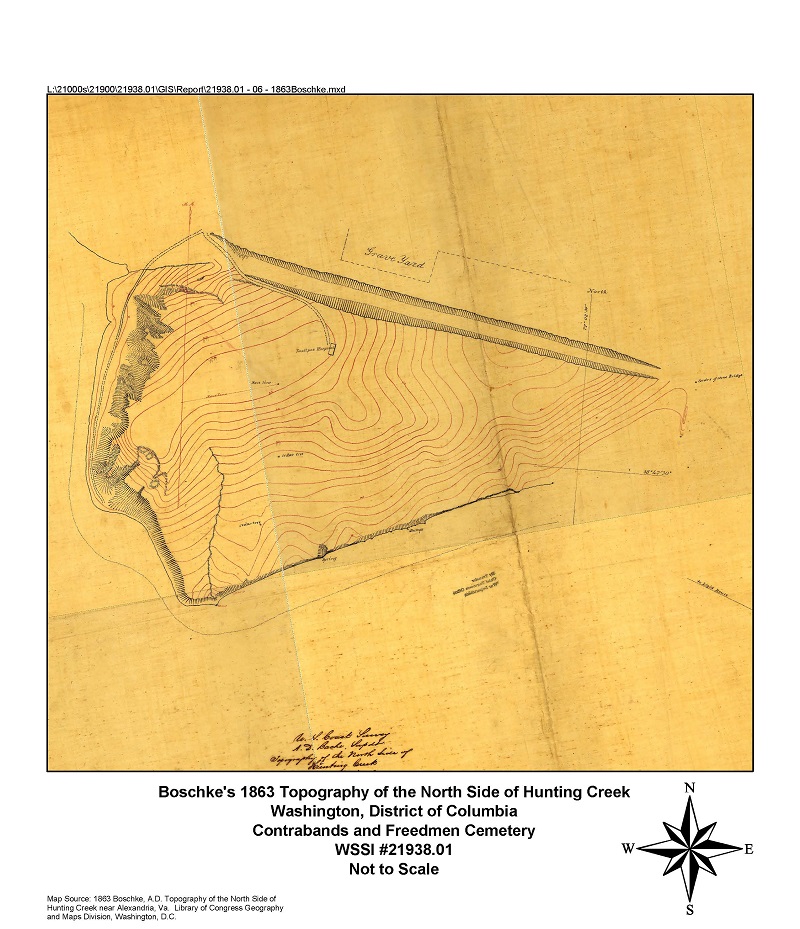

Historians have long deliberated about where interment of deceased freedom-seekers took place in Alexandria prior to the establishment of Freedmen’s Cemetery. In the 1980s and ‘90s, the answer to this question focused on the possibility that most burials occurred in the vicinity of a smallpox hospital set up by the military government south of Saint Mary’s Cemetery and the Manassas Gap Railroad cut that led from Jones Point. Some burials, particularly of smallpox victims, possibly took place in this location overlooking Hunting Creek, dubbed the “original” or “Old” Penny Hill Cemetery following the lead of an “Old Bachelor” whose reminiscences were published in the Alexandria Gazette in 1861.[x] However, more recent research documents that prior to burials in Freedmen’s Cemetery, most African American individuals were probably laid to rest in what historians often call “New” Penny Hill Cemetery, established as a municipal burial ground on Payne Street in 1796.[xi]

“Old” Penny Hill

According to the “Old Bachelor,” the “original” Penny Hill Cemetery “at the extreme south end of Royal Street, bordering on Hunting Creek, nearly surrounded by the marsh,” served as the burial ground for yellow fever victims who succumbed to the disease during an 1803 outbreak.[xii] Although it no longer exists, Penny Hill Street shows up in this vicinity on plats and maps of 18th and 19th-century Alexandria and contributes to the impression that a burial place for paupers was present in the area. It is unclear when this probable public burying ground or “potter’s field” was established, but it could date to 1798 when an earlier yellow fever epidemic spurred the city government to establish a quarantine house nearby on Jones Point.[xiii] “Old” Penny Hill may therefore post-date the creation of “New” Penny Hill on Payne Street. Thus, the two cemeteries may have been roughly contemporaneously created, adding to the confusion of the “Old” and “New” designations.

Initially, historians inferred the presence of a Civil War-era cemetery near the “Old” or “original” Penny Hill burial ground because of an 1866 Alexandria Gazette article that referred to a fight that broke out at a gathering in “Grave Yard Hall,” a structure south of St. Mary’s Cemetery. Given its location, historians postulated that Grave Yard Hall was the same structure that housed the Civil War-era smallpox hospital when it was established in 1862.[xiv] Since the name of this building suggested that it was situated in or near a cemetery, historians contended that it was logical for smallpox victims to be buried nearby. It is perhaps noteworthy that in April 1862, the same month that the smallpox hospital was established, the military government assumed some accountability and began a tally sheet of the number of freedom-seekers dying in Alexandria.[xv] The start of this accountability perhaps relates to the rising number of smallpox victims, some of whom could have been buried in the vicinity of the hospital, especially when the treatment facility was in use from May to November of 1862

While knowledge of the cause of smallpox was limited, residents of 19th-century Alexandria clearly knew that exposure to those with smallpox could lead to infection. Quarantining, burning of clothes and other personal items, and burial remained the keys to a semblance of control over spread of the disease until vaccination became more common.[xvi] Keeping the victims and deceased out of the urban center may have thus become a priority that resulted in burial in or near “Old” Penny Hill located in the vicinity of the wartime smallpox treatment facility. A similar situation undoubtedly led to the well-documented burial of smallpox victims around Claremont Smallpox Hospital west of town when the latter facility replaced the treatment center south of St. Mary’s Cemetery.

Moreover, the fact that there appeared to be a pattern suggesting the use of the area south of St. Mary’s Cemetery for burials during epidemics of highly contagious diseases contributed to impressions and assertions that there were interments there during the Civil War. If the Old Bachelor’s reminiscences are correct, the “original” Penny Hill would have contained the remains of those who succumbed to yellow fever during outbreaks in the late 18th and early 19th-century. After the Civil War, with smallpox epidemics again ravaging the city in 1872 and 1873, Broomilaw Hospital, likely the same structure that was used during the Civil War, served as a quarantine and treatment facility. During these post-war outbreaks, the government allocated money for food, supplies, and burials. Funding for the latter suggests the possibility of a cemetery in the area near the hospital in the 1870s.[xvii] Thus, although direct evidence is lacking, the “Old” Penny Hill area could have been used as a potter’s field during the Civil War, as well as during earlier and later outbreaks of contagious diseases.

Source: A.C. Boschke, Topography on the North Side of Hunting Creek, 1863, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

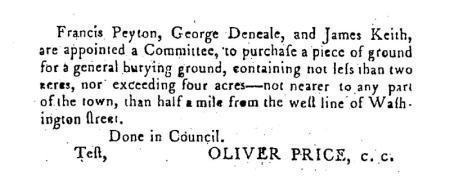

“New” Penny Hill

In 1796, the city purchased property and established “New” Penny Hill, a municipal cemetery on Payne Street just south of the city limits.[xviii] This area would develop into what is now known as the Wilkes Street cemetery complex. After “New” Penny Hill was founded, numerous churches bought land in this vicinity for establishment and expansion of their burial grounds when Alexandria’s Common Council restricted the creation of new cemeteries within the city in 1804. Today, thirteen cemeteries are situated in this section of Alexandria.[xix] Penny Hill initially served as the burial place for those with no religious affiliation or no access to burial in a church cemetery, but by or at the time of the Civil War, it seems to have become the primary final resting place for the indigent.[xx]

Documentation of Penny Hill as the main burying ground for the freedom-seekers prior to the establishment of Freedmen’s cemetery comes from the diary of Julia Wilbur and from a letter by Harriet Jacobs, although neither mentions the cemetery by name. On one of her first known recorded trips to the cemetery complex on November 16, 1862, Wilbur wrote in her diary that she:

went to the burying Ground. What sad sights I saw. It comprises several large squares. Each enclosed & with streets between them. The first one we went into has been an old burying place. Many stones are standing, some good ones & of late date, but they have made graves for soldiers here in any & every part of it. I think they often dig into others. Some of the Soldiers graves have head boards & some are not marked at all. A few have nice stones. The Contrabands are also buried here. [Emphasis added.][xxi]

Wilbur’s description of the “large squares…enclosed and with streets between them” could be none other than the Wilkes Street cemetery complex with the “old burying place” a reference to “New” Penny Hill. It is noteworthy that on July 17, 1862, Congress had authorized establishment of cemeteries for those who had died in service to their country, and Alexandria’s Soldiers’ Burying Ground was among the first to be created.[xxii] As a result, soldiers were no longer being buried at Penny Hill at the time of Wilbur’s visit, leaving this public cemetery as a place for interment of the indigent, including the freedom-seekers, until the establishment of Freedmen’s Cemetery.

In April 1863, Harriet Jacobs wrote a letter stating that the “refugees were buried in this town by the Government, beside many private burials….”[xxiii] Her statement again clearly suggests interment in Penny Hill on Payne Street, part of the complex where many churches had established their cemeteries, i.e. places of “private burial.”

On May 15, just one month later, Wilbur documented the conditions in what is again the cemetery complex, comparing the surrounding private burial grounds to the burial place for the freedom-seekers, noting it was “all green & nice but the potters field,” where the “contrabands are packed away, oh, such a place!”[xxiv] In a later diary entry, written two months after the establishment of Freedmen’s Cemetery, Julia traces the route of her rounds on April 10, 1864, which again suggests she is travelling to “New” Penny Hill in the Wilkes Street complex:

At 9 went with Jepitha to the Barracks, the Hospital, the Slave Pen and the Soldiers Rest. Then to the Soldiers Burying Ground, and through the cemetery to Potters Field. Such a heathenish place but no more Contrabands are buried there now. [xxv]

All the stops on this route lie in the general vicinity of the cemetery complex. Wilbur’s route took her from the Soldiers Burying Ground through the cemetery (one can infer cemetery complex) to Potters Field, i.e. “New” Penny Hill.

It is noteworthy that several diary entries of aid worker Julia Wilbur, as well as some other historical sources, indicate that interments of some African American people took place in other cemeteries in the Wilkes Street complex. This may have been especially true for free Black individuals who had resided in Alexandria prior to the war and had established connections with churches in the city.[xxvi]

Source: Alexandria Gazette, August 29, 1795

Other Burial Grounds for Freedom-Seekers In and Around Alexandria

Researchers have found evidence of several other cemeteries for interments of African American people in and around Alexandria, probably established prior to the creation of Freedmen’s Cemetery. The cemetery at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, situated in Fairfax County, Virginia, about two miles west of the city, is well-documented in the historical record. As with the interments of smallpox victims around the small hospital at “Old” Penny Hill, burials in the immediate vicinity of the Claremont Hospital helped to contain the spread of the disease in the more densely populated areas by keeping those who died of smallpox out of the city. The graveyard at Claremont included 77 individuals thought to be African American, moved after the war to an area of Arlington National Cemetery (part of Section 27).[xxvii]

To date, historians have found one reference, dating to 1873, that documents the presence of another burial ground on the south side of the railroad tracks just outside of the north wall of Alexandria National Cemetery:

[T]here are about (50) fifty graves. One I opened and found a body therein. These graves are arranged in rows parallel with each other…[xxviii]

The military authorities came to the conclusion that “Colored employees of the Quartermaster’s Dept. were buried in this place….,” noting that “[the] graves may be filled up, sodded, and trees planted, if the owners of the land (the O.A. & M.R.R. Co.) do not object.”[xxix] The estimate of fifty graves likely comes from the number of visible mounds or depressions in the ground. Although the military attributed these graves to workers of the Quartermaster’s Department, it is perhaps more probable that they represent burials of U.S. Military Railroad laborers, given the graveyard’s proximity to the hospital that was part of the railroad complex and the fact that the location of the graves appears to have been within the railroad right-of-way.[xxx]

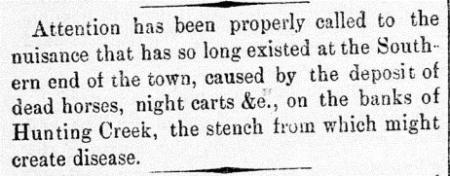

Source: Alexandria Gazette, January 30, 1864

Potter’s Field Conditions and Freedmen’s Cemetery Establishment

Source: Haverford University Library, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

The increasingly disgraceful conditions at “New” Penny Hill undoubtedly contributed to the establishment of Freedmen’s Cemetery by the military government. Julia Wilbur’s May 15, 1863, diary entry comparing the privately owned cemeteries in the Wilkes Street complex with Penny Hill reflected her growing concerns with the circumstances related to burials of the formerly enslaved people.[xxxi] As time went by and conditions in the cemetery apparently got worse, “heathenish” seemed to be Wilbur’s expressive word for the potter’s field setting. On January 21, 1864, she wrote, “The Potters field is the most heathenish looking place I ever saw. The[y] were put in holes rather than graves, and bare[ly] covered.”[xxxii]

Government records suggest that issues surfaced between the military and city administrators pertaining to the use of Penny Hill Cemetery during the winter of 1864. On the 21st of January, the same day that Wilbur wrote about the “heathenish” conditions of the potter’s field in her diary, correspondence addressed to C.A. Ware, the mayor of Alexandria, entreated him to “please sign an order for the burial of our negroes (paupers) now lying dead. Capt. Church is very anxious to have these ca—[cadavers?} disposed of, & any others that may occur before he can make other provisions in some suitable place not otherwise taken up, which he will do in a few days.”[xxxiii] That same day, word came from the city granting “Mr. Gladwin, Supt. Contrabands, …permission to bury negroes in Penny Hill until further notice….”[xxxiv] Given the documentation from Julia Wilbur and Harriet Jacobs that burials were already taking place at the increasingly “heathenish” city-owned Penny Hill, it is logical to infer that concerns about conditions in the potter’s field, including limited space, led the city to question whether the burial of freedpeople could continue in that location and that the federal government sought this permission, i.e. reauthorization, until a new suitable burial place could be found. Shortly after this interchange, Reverend Gladwin received orders to establish the new burying ground that would become Freedmen’s Cemetery.[xxxv]

Land Appropriation and Opening of the Burial Ground

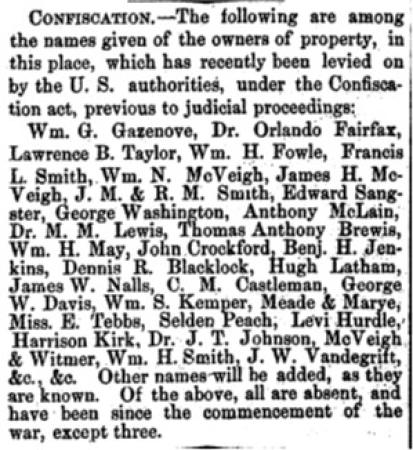

Source: Alexandria Gazette, July 23, 1863

The land appropriated for use as Freedmen’s Cemetery was part of a 5½-acre tract purchased by Francis Lee Smith in 1853. This parcel, outside of the official city limits at the time, extended into the middle of what would have been the platted southward extension of Washington Street,[xxxvi] which ended at Hunting Creek a few blocks farther south. Smith, a prosperous lawyer, acted as personal legal advisor to Mary Anna Custis Lee (wife of Confederate General Robert E. Lee).[xxxvii] Spending the war years in Liberty, Virginia, Smith and his family had left Alexandria, like many other Confederate sympathizers, when it fell under Union control,.[xxxviii] The family’s flight from the city paved the way for the use of Smith’s land by the military government as a burial ground for the freedom-seekers. In July 1863, the Alexandria Gazette noted that Smith’s property, likely including this southern parcel as well as Smith’s home in town, had “been levied by the U.S. authorities, under the Confiscation act, previous to judicial proceedings…”[xxxix]

Undoubtedly resulting from the conditions and lack of space at Penny Hill, the directive to Reverend Gladwin, Superintendent of Contrabands, to create the new burial ground came from General John P. Slough, the Military Governor of Alexandria, who was actually using Smith’s confiscated home as his own residence and initially as his headquarters.[xl] In later correspondence with Slough, Gladwin recounted the orders that led to the establishment of the cemetery on 1.5 acres of Smith’s parcel south of the city, including laying out the cemetery, fencing it, and beginning burials on March 7, 1864.[xli]

Reports on conditions on the southern outskirts of the city at the time of the cemetery’s creation indicate that the area had significant problems. In January 1864, the Alexandria Gazette called attention to “the nuisance that has so long existed at the Southern end of the town, caused by the deposit of dead horses, night carts, etc. on the banks of Hunting Creek….”[xlii] One month later, as preparations for the establishment of the cemetery were under way, the paper again noted:

The Corporation authorities ought really to do something to abate the horrible nuisance created by allowing the night carts to be emptied on the hills near the Catholic burying ground [St. Mary’s Cemetery]. When the wind is from the South, half the town almost is subjected to the annoyance which is so complained of, by the citizens generally.[xliii]

While it is not definitively known whether any of these offensive deposits were present on Smith’s appropriated property, the description of the location “on the hills near the Catholic burying ground” suggests that it is a possibility. Clean-up of the area apparently took place shortly after burials began. Appropriately, as reported in the Alexandria Gazette on March 29, the Quartermaster Department ordered “that offal and dead animals be removed from the southern region of Alexandria.”[xliv] Nevertheless, problems in the area apparently persisted, as the Alexandria Gazette reported in July that “the carcasses of dead horses continue to be thrown on the open grounds near the Catholic cemetery,” specifying that “[a]n example will be made of the offenders.”[xlv] Fencing of the cemetery property, completed by March 12, may have helped to protect the actual burial ground from these intrusive activities going forward, despite the offenses occurring in the vicinity. By the time Julia Wilbur visited the cemetery about a month after it opened, she noted, “It is as good a spot as could be obtained.”[xlvi]

Footnotes

[i] Reverend Albert Gladwin to John P. Slough, 16 December 1864, Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2053, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[ii] Testimony of Captain John C. Wyman, “An Official Inquiry into the Conduct of The Reverend Albert Gladwin, Superintendent of Contraband at Alexandria, Virginia;” 1 October 1863, archived in Office of the Adjutant General Colored Troops Division 1863, Record Group 94, G26-83, Box 15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., compiled by T. Michael Miller, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, 2004.

[iii] Alexandria Gazette, 29 September 1862.

[iv] “Local,” Alexandria Gazette, 26 November 1862; also see T. Michael Miller, “A Time for Remembrance-The Contraband Cemetery,” Memorial Day Address about Contraband Cemetery, May 1998, 1.

[v] Alexandria Gazette, 13 April 1863.

[vi] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 2.

[vii] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, Pocket Diary, 21 January 1864, 10 April 1864, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

[viii] Alexandria Gazette, 4 March 1864.

[ix] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, 11.

[x] Reminiscences of an Old Bachelor, Alexandria Gazette, 16 November 1861, 2, compiled by T. Michael Miller, on file Alexandria Library, Alexandria, VA.

[xi] Alexandria Gazette, 29 August 1795; Minutes of the Alexandria City Council, 1792-1800, 142; George Gilpin, MAPS-30, deposited with the Clerk for the Alexandria Circuit Court, Plat copied by H. L. Peyton from old Plat Book compiled by Reuben Johnson, cited in Penny Hill Burying Ground, on file Alexandria Library, Alexandria, Virginia; Alexandria Gazette, 29 August 1795.

[xii] “Reminiscences of an Old Bachelor,” Alexandria Gazette, 16 November 1861, 2, compiled by T. Michael Miller, on file Alexandria Library, Alexandria, VA.

[xiii] Krystyn Moon, A Brief History of Public Health in Alexandria and Alexandria’s Health Department, (Fredericksburg, VA: University of Mary Washington, 2014), 5.

[xiv] Alexandria Gazette, 10 May 1862, 11 August 1866; Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865, 2018,” 8, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xv] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, Accession Number 1100408, March 26-27, 1864, 2.

[xvi] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865, 2018,” 12, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf

[xvii] T. Michael Miller, “Fun and Frivolity at Broomilaw Point,” The Fireside Sentinel I (3), HuntingTerrace Vertical File, Alexandria Archaeology, Alexandria, VA; Krystyn Moon, A Brief History of Public Health in Alexandria and Alexandria’s Health Department, (Fredericksburg, VA: University of Mary Washington, 2014), 5; Timothy Dennée, email communications with Francine Bromberg, 25 September 2019, research file available at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xviii] Alexandria Gazette, 29 August 1795; Minutes of the Alexandria City Council, 1792-1800, 142; George Gilpin, MAPS-30, deposited with the Clerk for the Alexandria Circuit Court, Plat copied by H. L. Peyton from old Plat Book compiled by Reuben Johnson, cited in Penny Hill Burying Ground, ms, on file Alexandria Library, Alexandria, Virginia; Alexandria Gazette, 29 August 1795.

[xix] Mark D. Greenly, Those Upon Whom the Curtain Has Fallen, Past and Present Cemeteries of Old Town, Alexandria, Virginia, Alexandria Archaeology Publication No. 88, Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, 1996.

[xx] Mark D. Greenly, Those Upon Whom the Curtain Has Fallen: The Past and Present Cemeteries of Alexandria, VA, Alexandria Archaeology Publication no. 88, 41-42, Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, 1996; Reuben Johnson, Penny Hill Burying Ground, ms, on file Alexandria Library, Alexandria, Virginia.

[xxi] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 16 November 1862, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf. Note that African American men were not recruited until after January 1, 1863; therefore, the soldiers mentioned in this account of burials in Penny Hill were white. Moreover, by the time of this writing, interments of soldiers, already totaling several hundred, had been taking place in the military burial ground (Soldiers’ Cemetery, now Alexandria National Cemetery), established earlier in 1862.

[xxii] National Cemetery Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, https://www.cem.va.gov/facts/Dates_of_Establishment_1.asp.

[xxiii] Harriet Jacobs to Pastor J. Sella Martin, 13 April 1863, The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, vol. 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

[xxiv] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, Pocket Diary, 15 May 1863, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Haverford, Pennsylvania..

[xxv] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, Pocket Diary, 10 April 1864, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

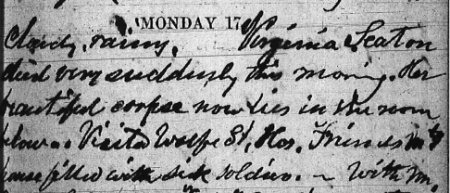

[xxvi] It is noteworthy that Julia Wilbur’s diary entries, as well as some other historical sources, indicate that interments of some African American individuals in Alexandria took place in other cemeteries in the Wilkes Street complex. This may have been especially true for some free Blacks who had resided in the City prior to the war and had established connections with churches in the city. For instance, the November 19, 1862, burial of Virginia Seaton likely occurred in Trinity Church Methodist Cemetery. Virginia was the daughter of George Seaton, prominent free African American master carpenter and businessman who served as a delegate in the Virginia Assembly following the war. Julia Wilbur’s diary records her death on November 17 followed by burial on the 19th: “Virginia Seaton died this morning very suddenly after an illness of a few days wh. was not thought to be dangerous. The eldest child & in her 15th. year. They feel it very deeply, as they are an affectionate family. —I cannot realize that there is death in the house although I saw her die. She is laid out prettily & placed in an elegant Coffin in the parlor below. Alex. Wednesday Nov. 19th. 1862 … Virginia Seaton’s funeral this P.M. I went with them to their burying ground.” The reference to “their burial ground” likely points to interment in Trinity Methodist,where her grandfather and aunt had been laid to rest in the 1840s, as documented in Wesley Pippenger’s Tombstone Inscriptions of Alexandria, VA, vol I, Family Line Publications, 1991.

[xxvii] Cited in Tim Dennée, African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865, 2018, 19-21, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf

[xxviii] G.W. Harbison, Superintendent Alexandria National Cemetery, to William Myers, Brevet Brigadier General and Dept Quartermaster, 18 August 1873, Record Group 92, Records of the Office of Quartermaster General, Entry 576, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., cited in Timothy Dennée, email communication with Francine Bromberg, 25 September 2019, research file available at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xxix] Wm. W. Belknap, Sec’y of War, Endorsement to 18 August 1873 correspondence, Record Group 92, Records of the Office of Quartermaster General, Entry 576, General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., cited in Timothy Dennée, email communication with Francine Bromberg, 25 September 2019, research file available at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xxx] Timothy Dennée, email communication with Francine Bromberg, 25 September 2019, research file available at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA.

[xxxi] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, Pocket Diary, 15 May 1863, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

[xxxii] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, Pocket Diary, 21 January 1864, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

[xxxiii] R. Johnston to C. A. Ware, 21 January 1864, Record Group 105, Entry 3253, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxiv] Charles A. Ware, 21 January 1864, Unregistered Letters Received March 1863 to April 1866, 21 January 1864, Record Group 105, Entry 3853, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxv] Reverend Albert Gladwin to John P. Slough, 16 December 1864, Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2053, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xxxvi] Alexandria Deed Book T3:11-12, 2 June 1853, Alexandria Circuit Court, Land Records, Alexandria, VA.

[xxxvii] “Taylor Whig Club,” Alexandria Gazette, 1 September 1848, 3.

[xxxviii] Lynchburg News, circa 14 May 1877. During the mid-nineteenth century, numerous unincorporated towns were named Liberty, making positive identification of Francis Smith’s location difficult.

[xxxix] Alexandria Gazette, 23 July 1863.

[xl] William F. Smith and T. Michael Miller, A Seaport Saga, Portrait of Old Alexandria, Virginia (Norfolk: The Donning Company 1989), 89.

[xli] Reverend Albert Gladwin to John P. Slough, 16 December 1864, Letters Received, 1862-1865, Records of the Military Governor of Alexandria, Records of the United States Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393, Entry 2053, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xlii] Alexandria Gazette, 30 January 1864.

[xliii] Alexandria Gazette, 29 February 1864. St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery is located directly west of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery, across South Washington Street at 1001 South Royal Street.

[xliv] Alexandria Gazette, 29 March 1864.

[xlv] Alexandria Gazette, 11 July 1864. Archaeological investigations unearthed evidence of a cow buried in the floodplain deposits of the streambed downslope from and west of the cemetery. This find appears to confirm the dumping that occurred, at least downslope from the hills of the cemetery.

[xlvi] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 12 April 1864, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf.