The Lee Street Site: The Rise of Industry

A Community Digs its Past: The Lee Street Site

The Lee Street exhibit reveals the archaeological process and the history of Alexandria as seen through the lens of the Lee Street Site (archaeological site 44AX180) and several other waterfront sites.

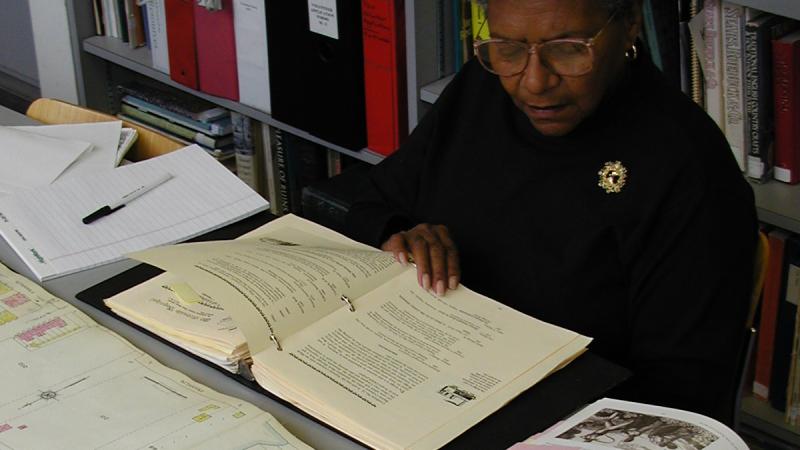

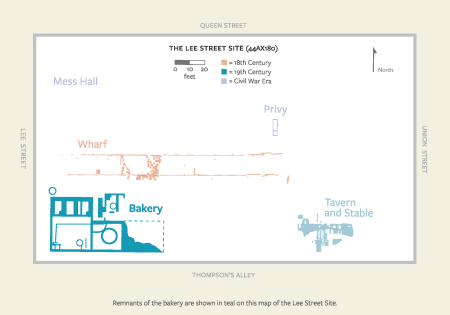

Preserved on the Lee Street Site was a cross-section of Alexandria's history from its founding in 1749 into the 20th century. Eighteenth-century wharves remained intact below remnants of a bakery, taverns, and residences that had sprung up on the bustling waterfront. The block was later used by the Union Army as a hospital support facility for the huge influx of soldiers during the Civil War. These layers of time were preserved under shallow foundations and a paved parking lot. The exhibit weaves together the story of the wharves, taverns, bakery and Civil War privy excavated at the corner of Lee and Queen Streets with the step-by-step process of archaeology from research and excavation to lab work and conservation.

19th Century - The Rise of Industry

Buried foundations show the industrialization of the waterfront.

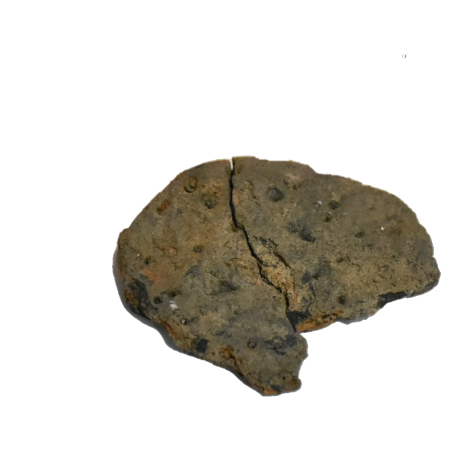

In the early 1800s, ships filled the harbor. Warehouses, taverns, bakeries, and other seaport industries lined the waterfront, supporting maritime trade. Alexandria’s bakeries made ship biscuits, also known as hardtack, for sailors. In the 18th and early 19th century, these bakeries relied on enslaved labor.

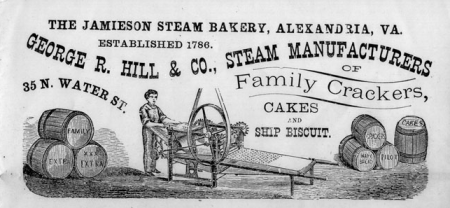

Robert Jamieson built a bakery on the corner of Lee Street in 1832. He pioneered the use of steam and mechanization to heat his ovens and increase production, relying less on enslaved labor. Archaeologists uncovered evidence of the Jamieson Bakery and its ovens during the excavation of the Lee Street Site.

The Wheat Economy

Alexandria was a gateway where raw materials were made into manufactured goods. Unlike other ports in the region, Alexandria switched from a primarily tobacco economy to wheat and flour. Bakeries made bread and biscuits from wheat from Western Virginia, and then sold these goods locally or shipped them down the Potomac River.

Industrialization and Manumission

Working in an industrial bakery was hot, hard work that relied on the labor of enslaved people and apprentices. People working in towns and cities experiences slavery differently than those on plantations, including greater access to freedom for some. White slaveholders in Alexandria bound enslaved apprentices to work for a set number of years. Some people bought their freedom, some were freed, and many others remained enslaved.

Though Robert Jamieson manumitted (freed) some enslaved people, he also benefitted from the forced labor of many others.

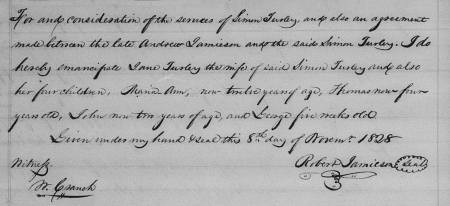

“For and consideration of the services of Simon Turley, and also an agreement made between the late Andrew Jamieson and the said Simon Turley. I do hereby emancipate Jane Turley the wife of said Simon Turley and also her four children, Maria Ann, now twelve years of age, Thomas now four years old, John now two years of age, and George five weeks old.

Given under my hand and seal this 8th day of November 1828.

Witness Robert Jamieson (seal)

W. Cranch”

Industrialization

The bakery changed hands over the course of the 19th century. During this time, the role of enslaved people in the industry changed due in part to mechanization, the abolitionist movement, and the changing economic cost of slavery.

Small-Scale Industry (1785-1823): Andrew Jamieson operated a series of bakeries in Alexandria. He was the second largest enslaver in the early 1800s. He enslaved 18 people, though not all worked in the bakeries.

Steam Power (1823-1861): Robert Jamieson, Andrew’s son, carried on and expanded the business. In 1832, a new three-story bakery manufactured many varieties of crackers, cakes, and breads. It was said that Queen Victoria liked them so much that she imported them for the Royal table.

The War Years (1861-1865): The Union Army commandeered the block that the bakery was on to use as a supply depot.

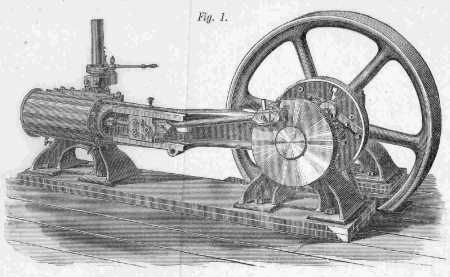

After the War (1869-1885): George R. Hill took over the business and continued to mechanize the operations. He installed a new steam engine, cracker machine, and cake making machine. By 1876, the bakery had four ovens and could make 600 cakes a minute.

Emerging Technology

Foundations and architectural remains show the increasing industrialization of the waterfront. Archaeology preserves evidence of the continued improvements and mechanization of the bakery.

Introduction of Steam

Jamieson’s Bakery transitioned from a process that was heavily reliant on enslaved labor to one that used steam mechanization.

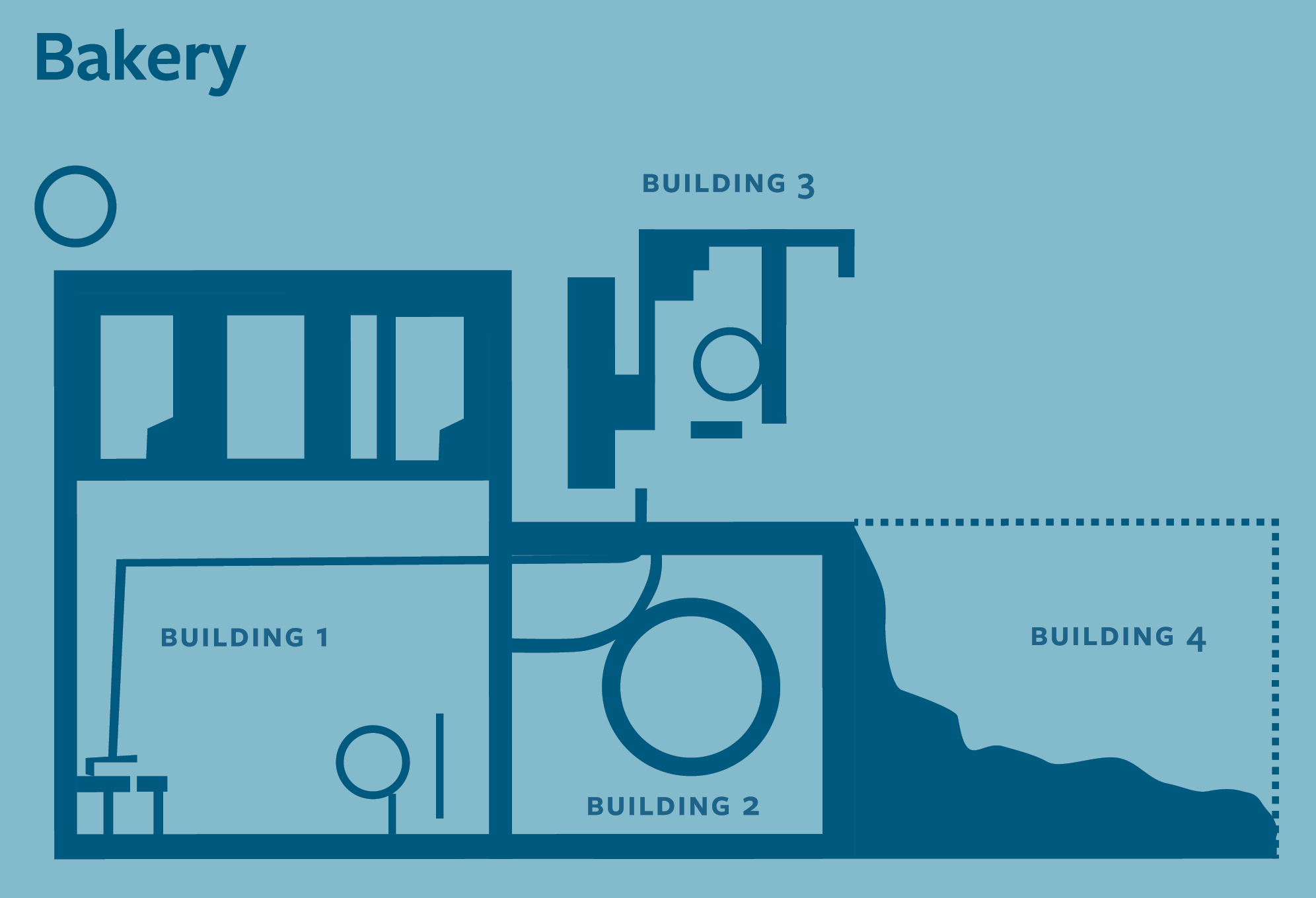

The bakery contained the remains of steam pipes, the foundations of four ovens, a chimney and firebox, a cistern, and wells.

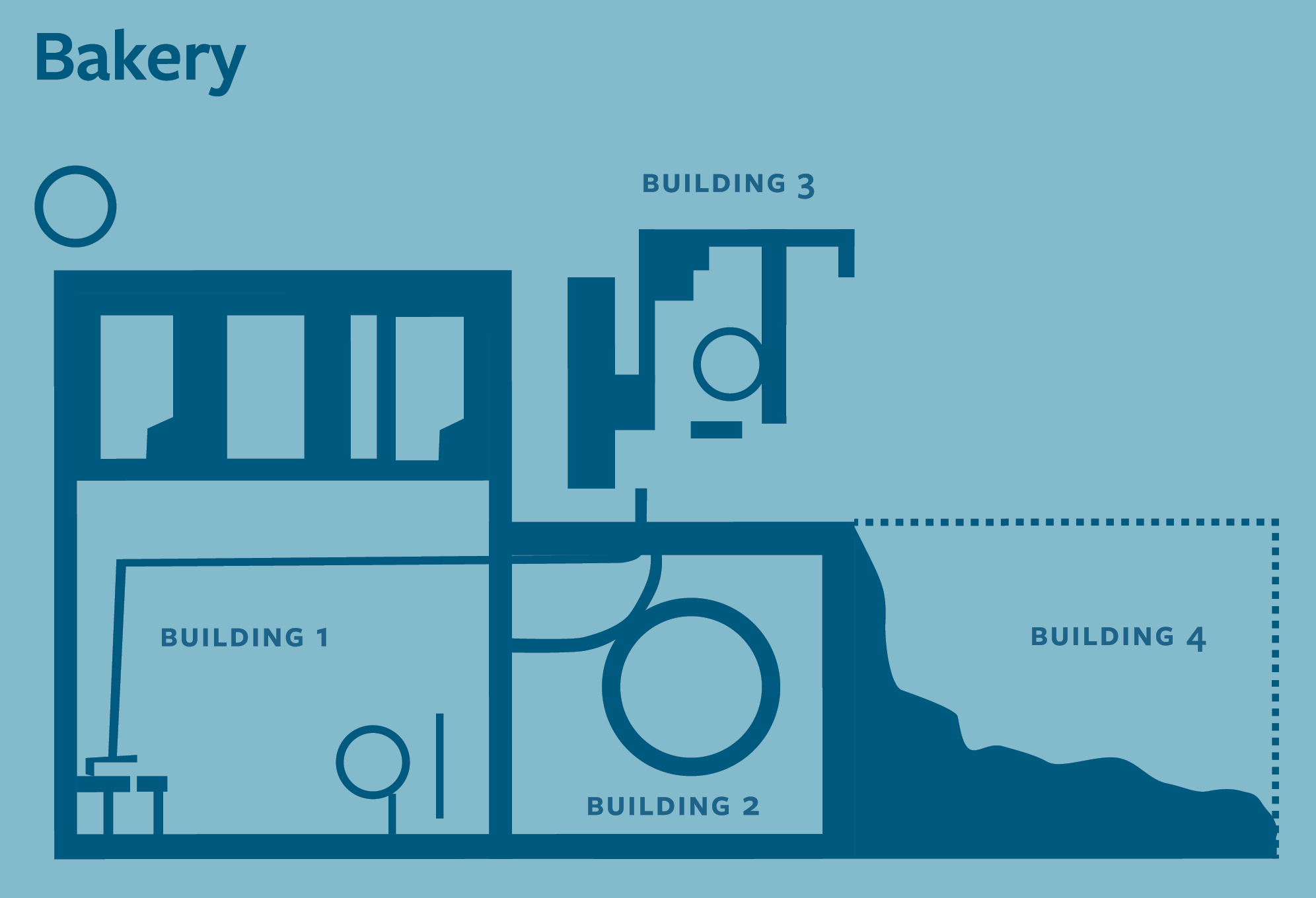

The Bakery

Building 1: By the 1870s, the main bakery building held the ovens, as well as cracker storage and packing. Cake steaming and packing took place on the third floor.

Building 2: The stone foundation adjacent to the main building contained a cistern. This cistern stored the water necessary to make steam, which powered the bakery.

Building 3: The bakery’s steam engine was located here.

Building 4: This may have been an earlier frame building associated with the earlier bakery. It likely burned during the Civil War. By 1888, the bakery was replaced by a grocery warehouse. Archaeologists found the remains of this warehouse above the earlier bakery, showing the layered history of the block.

Bottles in the well

Archaeologists found these bottles in the bakery’s well, which was filled with trash after the business moved across the street. They date from the Civil War, but were found along with artifacts discarded in the 1880s.