Community: Diseases and Medical Care

Community: Diseases and Medical Care

I found men, women and children all huddled together, without any distinction or regard to age or sex. Some of them were in the most pitiable condition. Many were sick with measles, diphtheria, scarlet and typhoid fever. Some had a few filthy rags to lie on; others had nothing but the bare floor for a couch.[i]

Harriet Jacobs, Aid Worker, Educator, and Author, Liberator, 1862

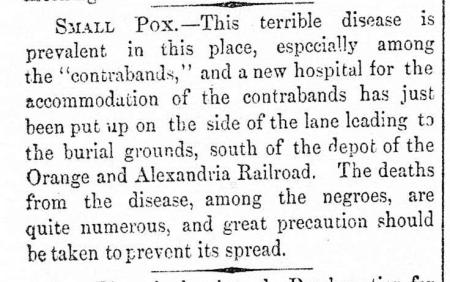

Local newspaper article describes the impact of smallpox in Alexandria, “especially among the ’contraband.’”

Source: Alexandria Gazette, December 1, 1862

The true peril of life in Alexandria’s burgeoning African American settlements, soldiers’ camps, and hospitals was the spread of diseases. After the stresses of their journey, many of the freedom-seekers were forced to live in make-shift shanties or camps because nothing more substantial was available. Unsanitary conditions, substandard housing, overcrowding, lack of food and clean water, and a shortage of supplies contributed to the prevalence of disease in these emerging neighborhoods, and those in government housing also faced significant overcrowding. The close quarters and weakened state left many of the refugees, especially the children and elders, susceptible to a wide range of diseases, with outbreaks of smallpox particularly troublesome.

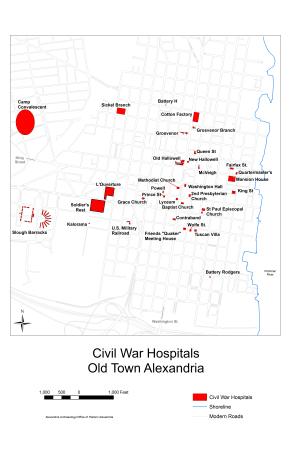

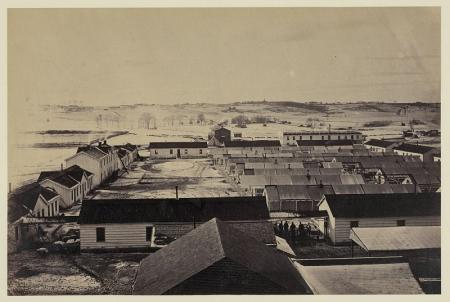

Alexandria’s function as a logistical base for the transport of supplies and troops also made it an important center for the treatment, care, and recuperation of the wounded and sick. Care for the soldiers, as well as the freedpeople,[ii] became the responsibility of the military and federal government. By the end of the war, Alexandria had become home to more than 30 hospitals with 6,500 beds. Medical facilities included churches, homes, the city’s largest hotel, and other buildings confiscated by the Union. Wounded and diseased patients filled the rooms and halls of a Quaker meetinghouse, a girls’ seminary, and a home belonging to the family of Robert E. Lee. Elsewhere, hospital complexes, constructed according to plans drawn up by the Quartermaster-General in Washington, extended over city blocks. In the long, ventilated barracks, usually made of wood, patients were divided into wards, in keeping with the “best practices” ideals for medical care of the mid-19th century.[iii] A few miles beyond the city limits, the Union also constructed Fairfax Seminary Hospital in what is now western Alexandria on the grounds of the Protestant Episcopal Theological Seminary (now named Virginia Episcopal Theological Seminary).

Source: U.S. National Library of Medicine; http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/64730880R

The 30-plus hospitals established in and around Alexandria during the war included three smallpox facilities designed to quarantine the highly contagious victims of the disease on the outskirts of the urban center. In addition, the military government designated several general hospitals as locations for treatment of the city’s African American population. These segregated facilities included the Contraband Hospital, established in the early years of the war and often cited by aid workers as inadequate, at best. L’Ouverture Hospital, designed and built to provide state-of-the-art care for its time, eventually replaced the Contraband Hospital for treatment of the USCT and African American civilians.

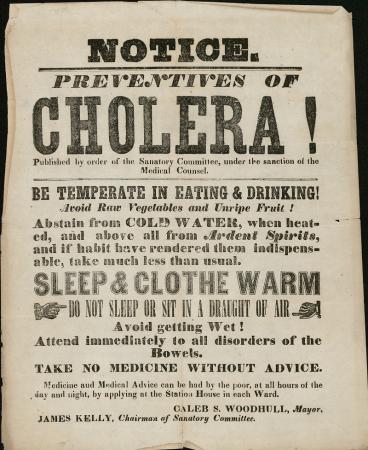

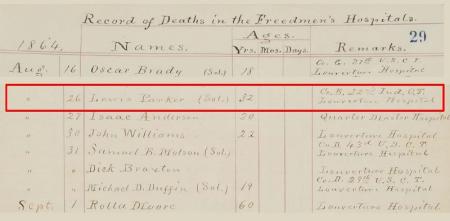

Knowledge of the diseases plaguing those living in Alexandria during and just after the war comes from a variety of documentary sources, including newspapers, hospital and government records, such as the Book of Records, as well as diaries and letters of aid workers.[iv] The most vulnerable members of the population, children and the elderly, were obviously the most susceptible to falling ill and least likely to recover. In addition to smallpox, typhoid, cholera, pneumonia and bronchitis, erysipelas and scarlet fever (now known to be caused by streptococci bacteria), diphtheria, measles, malaria (called remittent fever in the 19th century), and tuberculosis (consumption in 19th-century parlance) are among the infectious diseases found in the documents. Non-communicable diseases and conditions included rheumatism, neuralgia, hernias, ulcers, epilepsy, as well as edema (dropsy) and other heart complications. Malnutrition contributed to scurvy and anemia, although in some cases, the latter may also have been caused by what is now known as sickle-cell, a genetic condition that affects red blood cells’ ability to carry oxygen. Exposure to extreme heat or cold occasionally led to additional reported medical issues. And, of course, documentary sources also draw attention to injuries primarily associated with the combat troops, such as gunshot wounds, contusions, and fractures.

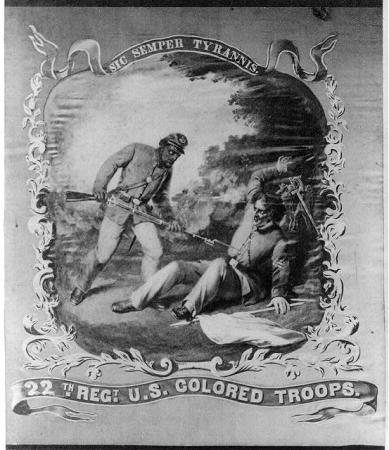

It is noteworthy that soldiers suffered from many of the same maladies as the freedom-seekers, and those in hospitals were almost twice as likely to die from disease than from battle wounds. The USCT fared even worse than their white counterparts. Health care for the soldiers of the USCT, although “deemed officially adequate…according to Union Army Medical Department policy and practice,” was notably worse than that provided for the white soldiers.[v] Comparisons of death rates between white and Black forces highlight the inequitable effects of this disparity:

[T]he mortality rate for disease was 55 per thousand per year among white volunteers, but 133 per thousand among black troops. These percentages indicate that a black soldier who had cholera or smallpox or one of the other prevalent camp diseases was more than twice as likely to die as his white compatriot.”[vi]

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Smallpox and Quarantine Hospitals

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

During the Winter and Spring the small pox made dreadful ravages among [contrabands]. No measures were taken at first to prevent it and it spread all over the city. There were many cases among the citizens. Of the contrabands, we think about 700 died of the disease.[vii]

Julia Wilbur, Twelfth Annual Report of the Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society, 1863

Perhaps the most devastating disease confronting both soldiers and civilians in Alexandria was smallpox. Epidemics ravaged the city throughout the course of the war. In general, smallpox, as well as other communicable diseases, prevailed in the vicinity of urban areas, perhaps especially among the freedpeople who were living in close quarters. A November 1862 Alexandria Gazette reported that “small-pox among the ‘contrabands’ in this place is said to be increasing.”[viii] One of Julia Wilbur’s letters further documents the rampant spread of smallpox in the city’s neighborhoods as well as among the soldiers:

Small pox ambulances may be seen in every part of the city. I think it is all over & all around us. The 19th. Conn[ecticut] Reg[imen]t is encamped a little west of us. An officer of this Reg[imen]t told Mr. W[hipple] last night that 90 of their men had black measles, but we know when they talk about black measles, that it is very likely to be small pox [sic]. …I hear that there is a great deal of it in Washington. How dreadful it will be if it is in the army. Poor soldiers. [ix]

With recognition of the highly contagious nature of smallpox, of the devastation that the disease could cause to the troops, and of the effects that the decimation would have on the Union war effort, the Army required vaccinations for all soldiers. However, success in completely fulfilling this initiative remained elusive. Moreover, few civilians had smallpox vaccinations prior to the start of the war, and the disease undoubtedly spread more quickly among the freedom-seekers given their living conditions.[x] By the end of September 1862, with smallpox on the rise, the number of deaths had increased to six African American people per day in Alexandria. Shortly thereafter, the military governor, Brigadier General John P. Slough, appointed a doctor to treat the freedpeople and protect the health and safety of the community. A vaccination program for the refugees began, but the inoculation of all who could be exposed to the virus remained a huge challenge.[xi]

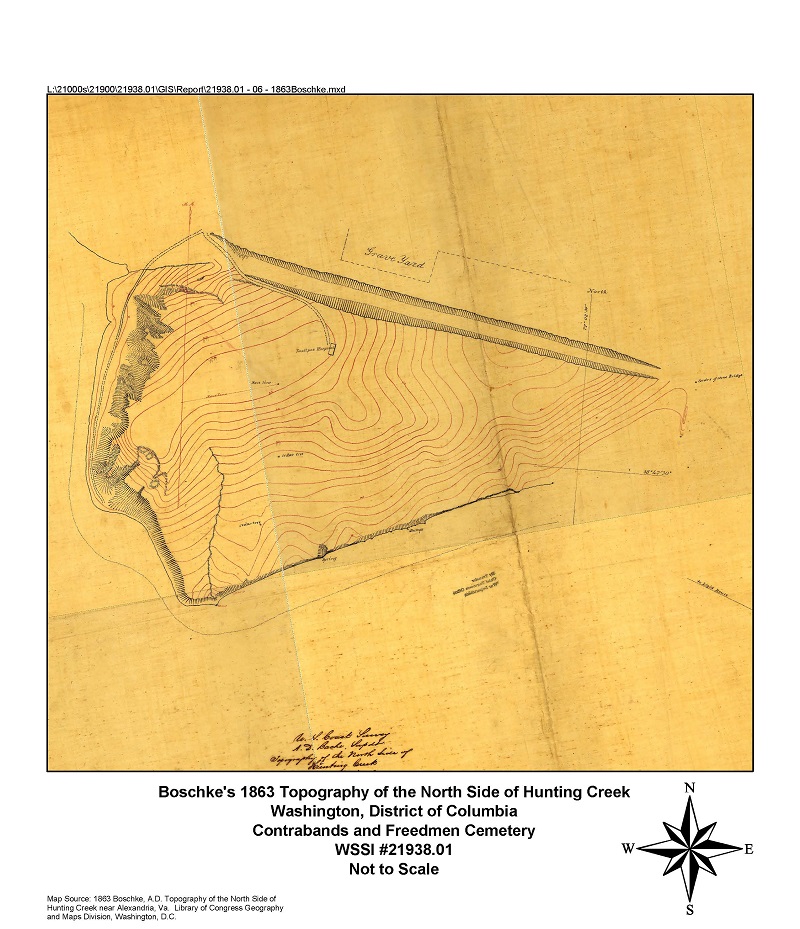

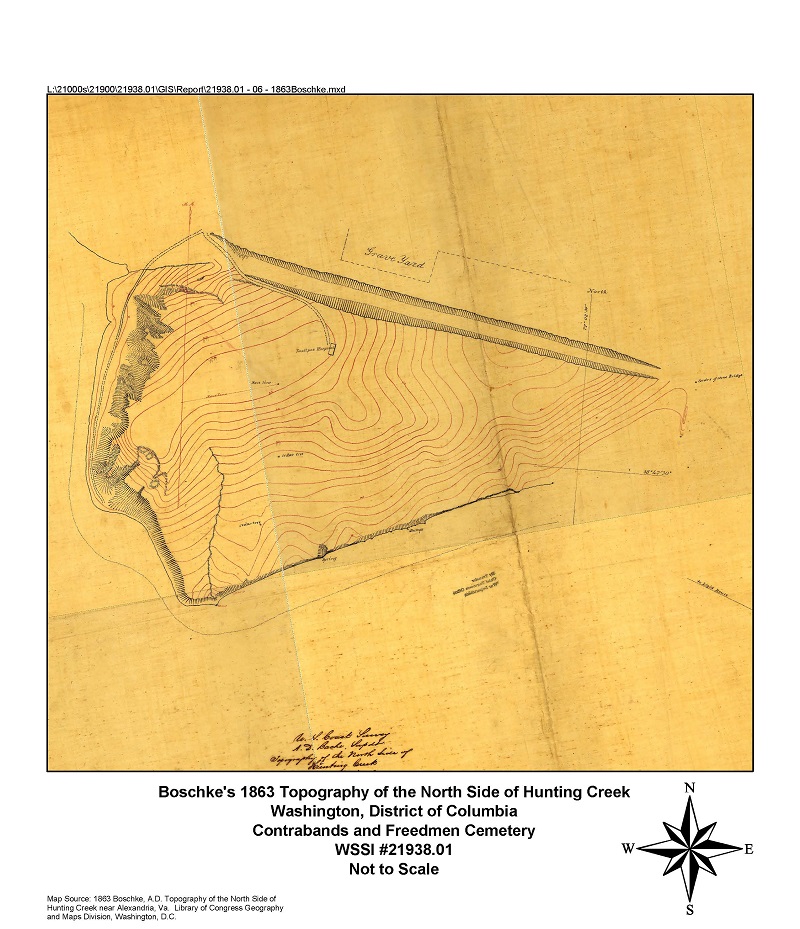

Most of the freedom-seekers who contracted smallpox (also called eruptive fever) would likely have been transferred to one of the specialized smallpox hospitals outside of the more populated areas of the city. Smallpox patients found themselves sent to the Smallpox Hospital overlooking Hunting Creek at the southern edge of town, to Claremont Hospital in Fairfax County, or possibly to Kalorama, reportedly another smallpox hospital near the United States Military Railroad complex.[xii] For the most part, African American nurses and laborers tended to the needs of patients in the smallpox hospitals.[xiii]

Smallpox hospitals did not provide treatment for wounds or general illnesses but functioned more like quarantine facilities to protect the community from the spread of the deadly infection. Once contracted, there was no cure, and patients either struggled through or succumbed to the disease. Care was mainly palliative, with alcohol perhaps serving as the most common “medicine.”[xiv]

Source: Alexandria Archaeology, Alexandria, VA

View full-size map

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Unnamed Smallpox Hospital, South End of Town

The establishment of a smallpox hospital at the southern end of the city resulted from a plea by the president of the Alexandria Board of Health to City Council in mid-April 1862. Citing an inability “to order any case of contagious disease out of the City” and a refusal of the Keeper of the Poor House “to receive any case of Small Pox [sic] at that place,” the board argued for the creation of a quarantine and treatment facility.[xv] Sometime in early May, the military government reacted, creating a smallpox hospital south of Saint Mary’s Cemetery along the Manassas Gap Railroad cut that led from Jones Point. At the end of November, after a warm-weather lull in the number of cases, three or four African American nurses were caring for at least 29 smallpox patients who had been sent to the facility. As the winter progressed, five or six people died at the hospital each day, with an equal number probably perishing in the town.[xvi] It is likely that many of these victims were buried in the vicinity of the hospital.

Source: A.C. Boschke, Topography on the North Side of Hunting Creek, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Kalorama Hospital

An Alexandria Gazette article in December 1862 reported on the establishment of a “new” smallpox hospital “for the accommodation of the contrabands…on the lane leading to the burial grounds.”[xvii] From this description, it is possible that the reporter is referring to Kalorama Hospital, situated on the north side of Wilkes Street, the road leading to the complex of cemeteries on the outskirts of the Civil War town.[xviii] The hospital itself was situated in the area that would become Douglass Cemetery, an African American burial ground established in 1895 and named for abolitionist Frederick Douglass.[xix]

Source: Drawn at Office of Chief Engineer and Gen’l Sup’t, U.S. Military Railroads of Virginia, Sept. 1865, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Claremont Hospital

Claremont Smallpox Hospital was located on a 300-acre Fairfax County plantation known as Clermont, just over two miles from the city of Alexandria. Its mid-nineteenth century owner, French Forrest, fled South, serving as acting assistant secretary of the Confederate Navy. With the abandonment of the property, Union troops occupied Clermont plantation in the summer of 1861, ravaging the stuccoed house and destroying many of the associated outbuildings for use as fuel and building materials for camps in the vicinity.[xx] In November 1862, Alexandria’s military governor confiscated the “defaced half-ruined” house for use as a hospital, a use that continued until the end of the war.[xxi]

Originally established for civilians who had contracted “eruptive fever,”[xxii] the hospital functioned primarily as a quarantine facility. By the end of January 1864, with other facilities in the city proving insufficient to deal with the magnitude of the problem, the cadre of largely African American nurses at Claremont had begun to care for soldiers as well as civilians, both Black and white. In mid-March, patients numbered 115, including 50 soldiers. Freedom-seekers continued to make up more than half, while USCT, especially members of the 23rd Infantry Regiment, were also quarantined there.[xxiii] The military government established a sizeable burial ground on the property for interment of those who died in the hospital.[xxiv] After the war, the Quartermaster’s Department exhumed at least 121 burials from Claremont and reinterred them in Arlington National Cemetery. The reburials included more than 70 African American civilians placed in what is now Section 27 of the cemetery.[xxv]

Claremont treated patients into September 1865. After the opening of L’Ouverture Hospital, a few patients who had begun to recover were transferred for recuperation.

As the Army prepared to relinquish the property after the war, workers set out to burn the smallpox patients’ clothing and bedding to prevent the spread of the contagious disease. However, the conflagration grew out of control, and the plantation house/hospital became a smoldering ruin.[xxvi]

Source: F.T. Miller, The Photographic History of the Civil War, 1912, cited in Tim Dennée’s “African American Civilians Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, 2007.

General Hospitals

You at a distance cannot image what a place this is at present. It was last Friday that 700 wounded were brought here. All day long the ambulances were busy in moving them from the boats to the hospitals. A great many slightly wounded were able to walk & will soon be well. In one hos[pital] I saw one ward filled up…[xxvii]

Julia Wilbur, Alexandria Aid Worker, Letter to Anna Barnes, 1862

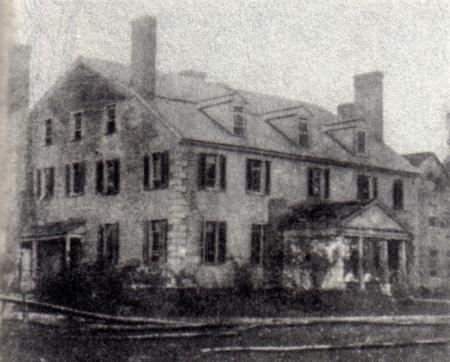

Generalized medical treatment for the freedom-seekers was almost non-existent in the early years of the war.[xxviii] Although the influx of African American refugees into the city continued, creating a critical need, no hospitals existed for their general care until early 1863 when the military government established the Contraband Hospital in the northern half of the confiscated house at S. Washington and Wolfe streets. Contraband Hospital served as the primary infirmary for the treatment of Black individuals with general illnesses and injuries until its closure in 1864.[xxix] L’Ouverture Hospital opened in February of that year, originally conceived by the government as a treatment center for the USCT, but quickly becoming the main treatment center for the freedpeople as well as African American soldiers. For a short time near the end of the war, Grace Hospital on S. Patrick Street also served as a treatment center for the USCT.[xxx].

Although Alexandria had more than 30 hospitals during the war, medical treatment for most of the African American individuals in the city took place in one of the segregated general hospitals specifically slated by the military government for their care. Exceptions to this policy appear in historical records indicating that a few Black employees of the Quartermaster and Commissary Departments were treated in the respective hospitals of these agencies.[xxxi]

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Contraband Hospital

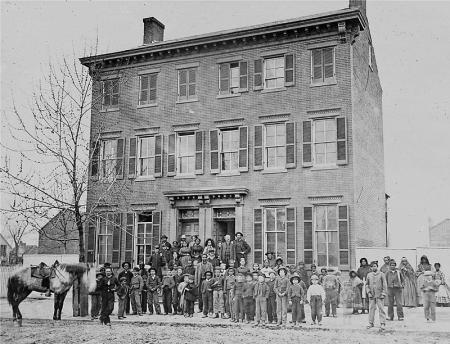

The military government established the Contraband Hospital in the northern half of the double house at 321-323 S. Washington Street, erected for china and glass merchant Robert Hartshorne Miller and his son, Elisha, in 1853.[xxxii] With the flight of the Millers from Alexandria at the start of the war, freedom-seekers moved into their abandoned homes until the Union commandeered the northern section for use as the hospital in February1863. The infirmary was officially known as the U.S. Hospital for Contrabands, Alexandria, more commonly referred to as the Contraband Hospital, “but also called ‘Bigelow’s Hospital [after John Reynolds Bigelow, a Manhattan doctor and surgeon to the 83rd New York Infantry appointed physician to Alexandria’s freedpeople],’ ‘the Colored Hospital,’ and simply ‘the hospital at the corner of Washington and Wolfe streets.’”[xxxiii] The southern half of the house became home to aid workers, including Julia Wilbur and Harriet Jacobs; schoolteachers; missionaries; and Reverend Gladwin and other officials working with the freedom-seekers.[xxxiv]

While patient registers from the Contraband Hospital have not been found, a newspaper account indicated that in the first few months, the hospital treated as many as 140 patients.[xxxv] Conditions in the facility remained an incredible source of concern for Julia Wilbur. She called the hospital a “loathsome place” where “poor women are dying of neglect.”[xxxvi] She blamed the chief surgeon, Dr. Bigelow, for many of the hospital’s problems:

The chief surgeon said “these sick people wanted nothing but corn bread and pork,” and he certainly seemed indifferent as to whether they had anything else. He said a hospital was unnecessary, but was very willing to draw a salery [sic] from Government on account of it. I did what I could for the sick and so did Mrs. J[acobs], but there was much suffering for want of proper food and nourishment. The assistant surgeon [Amos Pettijohn, at the time] did what he could to relieve the people, but there was little chance for him to carry out his humane feelings. [xxxvii]

The Contraband Hospital closed in February 1864 with the opening of L’Ouverture. The newly constructed facility became the center for the care and treatment of African American individuals, while Contraband Hospital remained a medical dispensary until after the war. The joined houses, still extant today, continued to serve as quarters for teachers and government officials throughout the war and during the Freedmen’s Bureau era.[xxxviii] A descendant of the Miller family recounted that the northern half retained the scars of its tenure as a medical facility, with “filled in bullet holes in the front parlor floor where operations took place…put there for draining of blood!”[xxxix]

Source: Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, Record Group 111, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

L’Ouverture Hospital

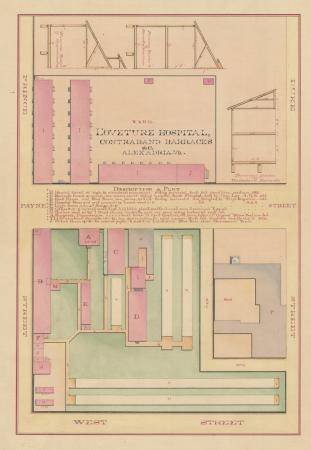

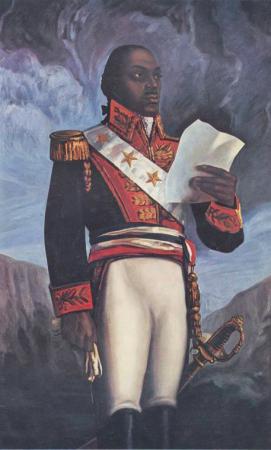

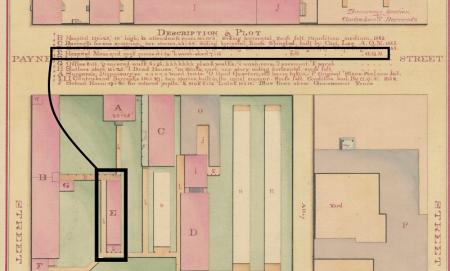

With the war continuing, and African American men engaging in combat, the military government recognized that Contraband Hospital would prove too small and ill-equipped to take on the treatment of Black soldiers and to continue to care for the refugee population. Seeking a more extensive and up-to-date hospital complex, especially considering the possible need for treatment of USCT transferred from the front to Alexandria, the military government began construction of a new state-of-the-art facility in November 1863 with the first patients admitted in February 1864.[xl] The hospital site encompassed most of the entire city block bounded by Prince, Payne, West, and Duke streets. It included the confiscated property on the grounds surrounding the Price, Birch & Company slave pen. Hospital wards and support facilities were built north and west of the infamous structure that had been turned into the Union Army jail fronting on Duke Street.[xli]

Source: Arlington County Book of Records for the Alexandria Freedmen's Cemetery, Accession No. 1100408, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA

Source: Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

The new medical facility was christened L’Ouverture Hospital in honor of General Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of the successful 1791 Haitian slave revolt. Harriet Jacobs recognized the significance of the moment in her remarks at the naming ceremony:

For the first time in Alexandria, we have met to celebrate a day made historical in our race—the day of British West India Emancipation…. Soldiers, when you return from the field of blood and strife, sick, wounded and weary, you will find a welcome here. We will bind up your wounds and administer faithfully unto you. Then take the dear old flag and resolve that it shall be the beacon of liberty for the oppressed of all lands, and of every soldier on American soil.”[xlii]

Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library

L’Ouverture Hospital was a fully developed example of the pavilion design for general hospitals. Refined by the military throughout the war, the pavilion design stressed good ventilation and provided for the grouping of patients with similar ailments in wards. Incorporating the “best practices” for medical care in the mid-nineteenth century, the design guidelines were officially adopted in July 1864, a few months after the opening of L’Ouverture by the Quartermaster Department:

These hospitals were to be made up of detached pavilions (rather than a single large building), with a separate building for each 60-bed ward. Other buildings to be included were a general administration building, dining room and kitchen for patients, dining room and kitchen for officers, laundry, commissary and quartermaster’s storehouse, knapsack-house, guard-house, dead-house, quarters for female nurses, chapel, operating-room, and stable.[xliii]

Source: Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, Record Group 111, National Archives, Washington, D.C. (ca. 1863)

Civil War hospitals like L’Ouverture developed into self-contained, sustaining communities to provide for the physical, social, and even spiritual needs of the hundreds of patients, medical personnel, and support staff who lived there.[xliv] The L’Ouverture complex included the Prince Street Barracks, where congregants of the newly established Shiloh Baptist Church met for services. As such, the area quickly became a center of African American life in Civil War Alexandria.

Source: Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

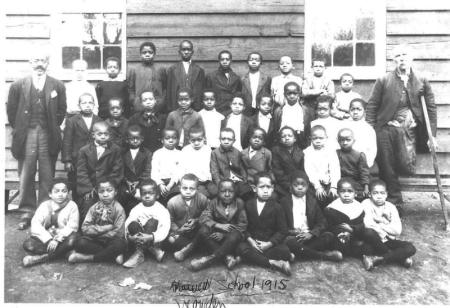

On October 7, 1865, six months after the war’s end, the last remaining 65 military patients at L’Ouverture Hospital were transferred to Slough General Hospital. By this time, L’Ouverture had cared for about 1,400 patients, including an estimated 66 new civilian patients a day.[xlv] The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (Freedmen’s Bureau) took over administration of L’Ouverture until it closed at the end of 1867.[xlvi] Two wards of the hospital continued to treat freedpeople during the Freedmen’s Bureau era. The associated barracks provided housing, and a school established in the barracks area continued in use until 1867 when new schools for African American students opened in Alexandria.

Source: Alexandria Black History Museum

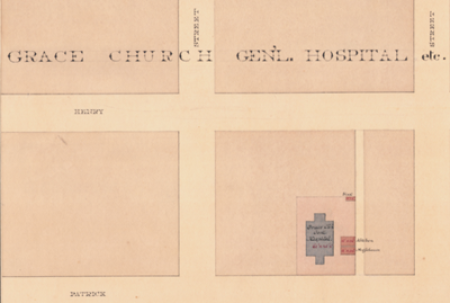

Grace Church Hospital

In June 1862, the military seized Grace Episcopal Church at 207 S. Patrick Street for use as a hospital. The congregation had formed in the mid-1850s with the new church building consecrated in October 1860, just eight months before the Union took control of the city.

For more than two years, Grace Church Hospital treated only white soldiers, but on November 30, 1864, they were transferred to Sickel Barracks General Hospital, and the first 43 African American soldiers were admitted. Patient registers indicate that admissions to the hospital peaked on November 30 and December 6, 1864, and on March 6, 1865, suggesting the possibility of transports to Alexandria as a result of the fierce battles near Petersburg, a siege that included significant participation of the USCT. Of the 111 patients on the 1864-65 registers (including at least two American Indian soldiers), 11 suffered from gunshot wounds. The hospital closed on April 29, 1865, with 85 remaining patients transferred to L’Ouverture.[xlvii]

Source: Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Footnotes

[i] Harriet Jacobs, “Life Among the Contrabands,” Liberator, 5 September 1862, cited in Jean Fagan Yellin, editor, The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, Volume 2 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 400.

[ii] W. Michael Byrd and Linda A. Clayton, An American Health Dilemma: A Medical History of African Americans and the Problem of Race (New York, NY: Routledge, 2000), 342 and 386.

[iii] “Union Hospitals in Alexandria, A Short History,” Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria VA, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-sites/union-hospitals-in-alexandria.

[iv] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf; Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf; Tim Dennée, “African American and American Indian Patients in Grace Church Branch, Second Division General Hospital, November 30, 1864 to April 23, 1864,” http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/gracechurch.pdf; April MacIntyre, “Comparative Study of Disease and Injury in United States Colored Troops (USCT) and White Troops treated at Grace Church G.H. and Grosvenor G.H., Alexandria, VA, from August 1864-April 1865,” Historical Archaeology student paper, George Washington University, 2013, on file Alexandria Archaeology Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA; Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va., Library of Virginia, Richmond, Accession Number 1100408.

[v] W. Michael Byrd and Linda A. Clayton, An American Health Dilemma: A Medical History of African Americans and the Problem of Race (New York, NY: Rutledge, 2000), 386.

[vi] Richard F. Selcher, Civil War America: 1850-1875 (New York, NY: Infobase Publishing, 2006), 395.

[vii] Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society, Twelfth Annual Report of the Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society (Rochester, NY: A. Strong & Co., 1863), 14, cited in Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 9. http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[viii] Alexandria Gazette, November 10, 1862.

[ix] Julia A Wilbur to Anna M.C. Barnes, December 24, 1862, Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society Papers 1851-1868, William L. Clements Library, the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, cited in Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 9,http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[x] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 7, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xi] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 8, 12, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xii] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 9-11, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xiii] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 16-18, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xiv] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 12, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xv] Accounts of the Alms House and Other Facilities of the Poor, 1813-1876, cited in Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 8, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xvi] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 8, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xvii] Alexandria Gazette, December 1, 1862.

[xviii] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 9, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xix] “Union Hospitals in Alexandria,” Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-sites/union-hospitals-in-alexandria; “Historic Cemeteries of Alexandria,” Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria, VA, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-sites/historic-cemeteries-of-alexandria#AfricanAmericanCemeteries.

[xx] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865, 2018,” 2-3, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf. Spelling for the hospital’s name reflected a change made by the military government when the hospital was created on the grounds of the Clermont plantation.

[xxi] Cited in Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865, 2018,” 9, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xxii] The term, Variola, the scientific name for smallpox, comes from reference to the eruption of spots or pimples. The term varioloid is reserved for milder cases of the disease, often occurring in the 19th century even after vaccination; many individuals, including Julia Wilbur, were inoculated multiple times to ensure immunity.

[xxiii] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 10-11, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xxiv] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 19-21, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xxv] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 19-21, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xxvi] Tim Dennée, “African-American Civilians and Soldiers Treated at Claremont Smallpox Hospital, Fairfax County, Virginia, 1862-1865,” 2018, 18, 24-48, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/claremont.pdf.

[xxvii] Julia A. Wilbur to Anna Barnes December 22-24, 1862, Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society Papers, 1851-1868, William L. Clements Library, the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

[xxviii] Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 12, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf

[xxix] Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 12-13, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf.

[xxx] Tim Dennée, “African American and American Indian Patients in Grace Church Branch, Second Division General Hospital, November 30, 1864 to April 29, 1865,” 1-2. http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/gracechurch.pdf.

[xxxi] Book of Records, Containing The Marriages and Deaths That Have Occurred, Within The Official Jurisdiction of Rev. A. Gladwin: Together, With any Biographical or Other Reminiscences That may be Collected. Alexandria, Va., Library of Virginia, Richmond, Accession Number 1100408.

[xxxii] Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 2-3, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf

[xxxiii] Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 12-14, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf.

[xxxiv] Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 12, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf.

[xxxv] The Liberator, April 10, 1863, cited in Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 15, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf.

[xxxvi] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 7 May 1863, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, transcription at https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1860to1866.pdf, cited in Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 16, https://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf.

[xxxvii] Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, Thirteenth Annual Report of the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society (Rochester: Rochester Democrat Steam Printing House, 1864), 13, cited in Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 15, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf.

[xxxviii] Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 17-19, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf

[xxxix] Cited in Tim Dennée and the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, “A House Divided Still Stands: The Contraband Hospital and Alexandria Freedmen’s Aid Workers,” 2017, 19, http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/contrabandhospital.pdf.

[xl] Sarah Traum, Brian Corle, and Joseph Balicki, Documentary Study, Archaeological Evaluation and Resource Management Plan for 1323 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA, John Milner Associates for Harambee CEDC, 2007, 20-27, on file at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, VA.

[xli] Sarah Traum, Brian Corle, and Joseph Balicki, Documentary Study, Archaeological Evaluation and Resource Management Plan for 1323 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA, John Milner Associates for Harambee CEDC, 2007, 20-27, on file at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, VA.

[xlii] Cited in Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life, Civitas Books, 2004, 181.

[xliii] United States Surgeon General’s Office, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Part III, Volume I, Medical History (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1888), 943- 944, cited in Sarah Traum, Brian Corle, and Joseph Balicki, Documentary Study, Archaeological Evaluation and Resource Management Plan for 1323 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA, John Milner Associates for Harambee CEDC, 2007, 46, on file at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, VA.

[xliv] Nancy E. Boone and Michael Sherman, “Designed to Cure: Civil War Hospitals in Vermont,” Vermont History 69, no. 1+2 (Winter/Spring 2001), 178.

[xlv] Sarah Traum, Brian Corle, and Joseph Balicki, Documentary Study, Archaeological Evaluation and Resource Management Plan for 1323 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA, John Milner Associates for Harambee CEDC, 2007, vii, on file at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, VA.

[xlvi] Sarah Traum, Brian Corle, and Joseph Balicki, Documentary Study, Archaeological Evaluation and Resource Management Plan for 1323 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA, John Milner Associates for Harambee CEDC, 2007, 26, on file at Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, VA.

[xlvii] Tim Dennée, “African American and American Indian Patients in Grace Church Branch, Second Division General Hospital, November 30, 1864 to April 29, 1865,” 1-2. http://www.freedmenscemetery.org/resources/documents/gracechurch.pdf.