Community: The Race to Freedom

Community: The Race to Freedom

…No sooner had the armies, East and West, penetrated Virginia and Tennessee than fugitive slaves appeared within their lines. They came at night, when the flickering camp-fires shone like vast unsteady stars along the black horizon: old men and thin, with gray and tufted hair; women, with frightened eyes, dragging whimpering hungry children; men and girls, stalwart and gaunt,—a horde of starving vagabonds, homeless, helpless, and pitiable, in their dark distress.[i]

W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 1903

“A Ride for Liberty—The Fugitive Slaves,” ca. 1862. Painting by Eastman Johnson.

Source: Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Miss Gwendolyn O. L. Conkling

From the very start of the Civil War, enslaved African American people actively pursued their own freedom, as many had throughout centuries of enslavement. They flocked to territory under Union control, and by late May 1861, this included Alexandria. Running away from enslavement had always been fraught with danger as recapture could bring severe punishment. In addition, running away often meant separation from loved ones, perhaps forever. However, the conditions of war, particularly the absence of their enslavers and the proximity of Union soldiers, presented freedom-seekers with more opportunities to self-emancipate. With the federal recognition that freedom-seekers could contribute to the war effort, the self-emancipators became known as Contrabands, as in “contraband of war.” Freedom-seekers realized that there was a significant chance that they would not be sent back to their enslavers. This knowledge provided added incentive for African American people to assert their independence. The journey remained perilous, but for tens of thousands, it was a risk worth taking.

Expectedly, the journey to freedom was not an easy one. Passage through Confederate Virginia was typically on foot and often very dangerous. Julia Wilbur, an aid worker in Alexandria, recounted the stories told to her by the refugees who sought freedom at any cost within Union lines:

This woman started with her 3 children, only partly dressed, one in her arms, the other 3 or 4 yrs. old, went 6 miles through the woods that night. Any thing [sic] rather than be taken [by her enslaver]! The woman that brought away 6 said she fell twice with one in her arms & hurt its back, & it died after she got here. When they came here some of them road [sic] part way, but some of them “walked very fast” all the way, some of them died from fatigue & exposure, some took colds that they have not yet got over.[ii]

The vast majority of those seeking refuge and freedom in Alexandria were born and raised in Virginia, and most had been enslaved on farms and plantations in the counties in the northern part of the state. Others arrived from more distant parts of the Commonwealth, from Maryland, and from across the Confederate States. On August 26, 1862, the Alexandria Gazette published an article stating, “Large numbers of contrabands continue to arrive here, principally from the upper counties. Yesterday about 100 reached here.”[iii] By October, federal officials reported “there are almost seven thousand contrabands in the District and at Alexandria.”[iv] The numbers increased throughout the war with estimates in Alexandria reaching eight to ten thousand by 1865.[v]

Emancipation of formerly enslaved individuals living in Alexandria took place on January 1, 1863, with President Lincoln’s proclamation freeing those in the Confederate states participating in the rebellion. After the war, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Constitutional Amendments ended slavery throughout the nation; granted citizenship to all born in the U.S., including those formerly enslaved; and gave African American men the right to vote. However, equality and civil rights remained elusive as more than a century of discrimination followed the Constitutional Amendments and advances of the early post-war years of Reconstruction.

Becoming “Contrabands” at Fortress Monroe

Sir,--Your action in respect to the negroes who came within your lines from the service of the rebels, is approved….[Y]ou will refrain from surrendering to alleged masters any persons who may come within your lines. You will employ such persons in the services to which they may be best adapted, keeping an account of the labor by them performed, of the value of it, and of the expenses of their maintenance.[vi]

Secretary of War Simon Cameron, Letter to General Benjamin Butler, May 31, 1861

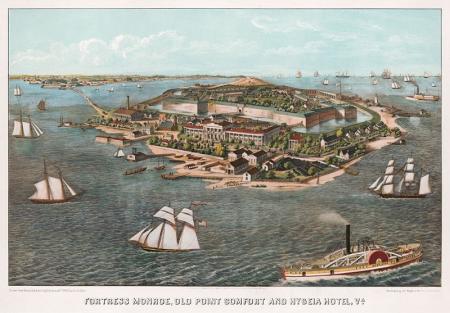

Fortress Monroe, Old Point Comfort & Hygeia Hotel, Virginia in 1861. Illustration by E. Sachse & Co., Baltimore. Published by Charles Magnus, New York.

Source: Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C.

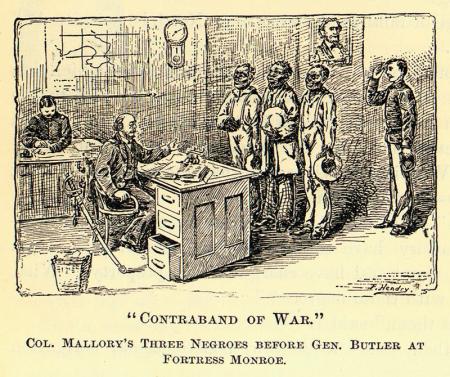

Like Alexandria, Fortress Monroe in Hampton Roads, Virginia, was in federal hands and became a natural beacon for self-emancipating Black Virginians escaping enslavement. A new policy with far-reaching implications emerged in May 1861 when three formerly enslaved African American men made their way to the fort and presented themselves to the newly appointed commanding officer of the post, Brigadier General Benjamin Franklin Butler. Enslavers of the three men had hired them out to the Confederate Army to aid in the construction of defensive batteries at Sewell’s Point across the mouth of the James River from Fortress Monroe. They had escaped at night and rowed a skiff to Old Point Comfort, where they sought asylum at the Union fortress.[vii]

General Butler took the position that, as Virginia considered itself a foreign power, he was under no obligation to uphold the Fugitive Slave Act and return the men. Instead, he considered them “contraband of war,” recognizing the possibility that their work could aid the Southern cause while noting their ability to contribute to the Union war effort.[viii] This declaration, followed by the actions of Union commanders in Alexandria and elsewhere, provided the federal government with an incredible workforce, meanwhile denying masses of African American workers to the South and helping to cripple the Confederacy.

Approval of Butler’s designation by Secretary of War Cameron provided for federal protection for the freedom-seekers and set the stage for them to aid in the Union war effort and to receive wages, food, and clothing for their labor. The word had travelled quickly among Virginia’s enslaved population, and the impact in the D.C. area was felt immediately. A New Jersey newspaper announced in June 1861, “Upwards of seven hundred slaves have escaped from Virginia within the past two weeks, and are now held by the Government forces as contraband of war. Value to the owners, seven hundred thousand dollars.”[ix]

The newspapers quickly adopted the sobriquet, referring to the freedom-seekers regularly as “Contrabands.” One Union officer wrote, “never was a word so speedily adopted by so many people in so short a time.”[x] The term was first used in an Alexandria newspaper in October 1861 by The Local News, which replaced the temporarily suspended Alexandria Gazette. The reference announced that “General [John E.] Wool has issued an order giving the ‘contrabands’ employed in fortress Monroe wages at the rate of $8 per month for the men, and $4 per month for the females.”[xi]

Within a few months, the status of formerly enslaved people as “contraband of war” became law in the First Confiscation Act of August 1861 by allowing the seizure of all Confederate property used to aid the war effort.[xii] A year later, on July 17, 1862, the Second Confiscation Act provided for the immediate liberation of all slaves who escaped to Union lines and authorized their employment to aid the Union cause.[xiii]

Under Butler’s designation and the confiscation laws, Contrabands were still considered property and often exploited. The act did not emancipate enslaved people, but rather removed them legally from the hands of their disloyal enslavers. Moreover, there was no direction or clarification in the acts of when or by what means true freedom was to be arranged, and many runaways were still detained and jailed with the expectation of being returned to their enslavers. Nevertheless, the designation paved the way for the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and, finally, the 13th Amendment in 1865, whereby all Contrabands truly became freedpeople.

“‘Contraband of War,’ Col. Mallory’s Three Negroes before Gen. Butler at Fortress Monroe,” n.d.

Source: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Emancipation

Alex. Jan. 2d. 1863

It is better than I feared. The President takes back nothing from his Emancipation Proclamation….[He] says all negroes that are able may be used in the service for garrisoning forts, manning vessels &c…. He calls it a fit & necessary war measure to put down rebellion, & believes it to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity.[xiv]

Julia Wilbur, Alexandria Aid Worker, Diary

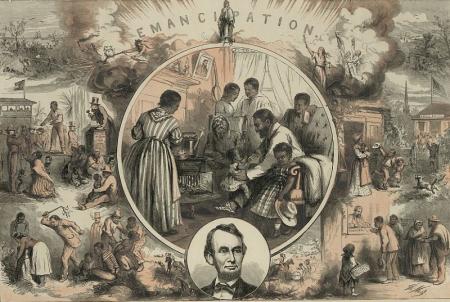

Source: Harper’s Weekly, 24 January 1863, LOT 14012, no. 361, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

The Contrabands and all enslaved people in Alexandria were legally freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation declared that:

all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.[xv]

In response to a preview of the proclamation in 1862, activist and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, formerly enslaved, proclaimed that “common sense, the necessities of the war, to say nothing of the dictation of justice and humanity have at last prevailed.”[xvi]

Most of the enslaved people in Alexandria had already gained some measure of freedom through Butler’s declaration and the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862. These had loosened the grip of enslavement bit by bit both on those who had been in bondage in the city at the time of the federal occupation and on the many who escaped to Alexandria seeking freedom. The Emancipation Proclamation created a definitive legal status as freedpeople for those in Alexandria and throughout the Confederacy.

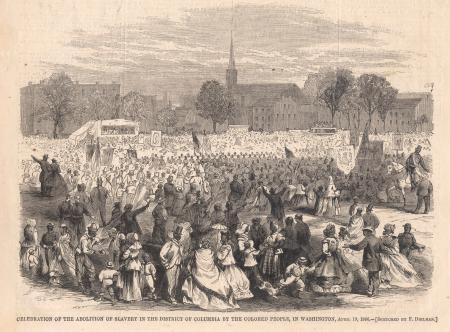

Emancipation was widely celebrated in the North. African American people and their white allies packed churches and meeting halls and celebrated the news. In Alexandria, Julia Wilbur implied in her diary that the New Year's Eve celebration ushering in 1863 did not presume to recognize the approaching change in status for the freedom-seekers, calling it “stoic,” occurring just “between 12 & 1 [with] some firing & the sound of buglist [sic], a band near us played beautifully.”[xvii] However, one year later on the first anniversary of the proclamation, the Alexandria Gazette featured a lively description of the festivities associated with its issuance, noting “a grand celebration by the colored people of this city and vicinity” on S. Washington Street “in honor of President Lincoln’s Proclamation of Emancipation….”[xviii]

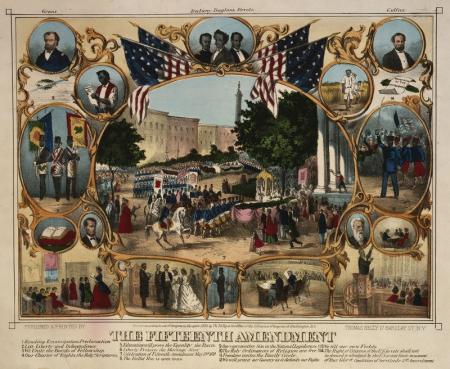

Although the presidential proclamation was reason to celebrate, it granted freedom only to those in the rebellious Confederate states. About one million people remained enslaved in the North. Slavery was not abolished until Congress ratified the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 6, 1865. In 1866, the 14th amendment was passed, guaranteeing due process and protection under the law to all American citizens and granting citizenship to all who were born in the U.S., thus extending rights to formerly enslaved people. Three years later, the 15th amendment was ratified; this amendment, (adopted in 1870) gave African American men the right to vote.[xix]

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Passage of the Fifteenth Amendment celebrated in this color lithograph by James C. Beard; Published by Thomas Kelly, 1870.

Source: Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA

Reconstruction

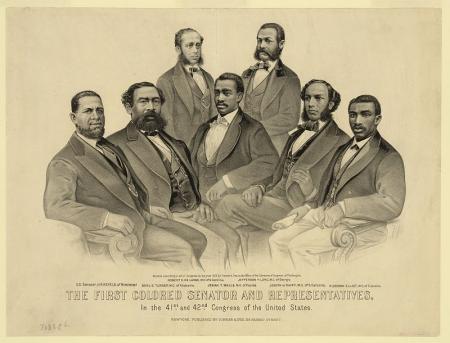

I am true to my own race. I wish to see all done that can be done for their encouragement, to assist them in acquiring property, in becoming intelligent, enlightened, useful, valuable citizens.[xx]

Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first African American man elected to the Senate in 1870

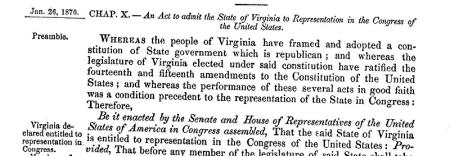

Source: Acts of the Forty-First Congress of the United States, Session II, Ch. 10, Page 62 (1870)

Reconstruction began in 1865 after the tumultuous war years. Vice President Andrew Johnson ascended to the presidency on April 15 immediately following the assassination of Lincoln, less than a week after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox. Members of Alexandria’s African American community expressed their grief at the loss of Lincoln by affixing black mourning cloth to the outsides of their homes.[xxi] The assassination left Johnson, a Southern Democrat with pronounced states’ rights views, in control of some aspects of Reconstruction. The new President pardoned Confederate sympathizers and leaders as part of his strategy,[xxii] actions that ultimately helped set the stage for the reestablishment of policies of white supremacy in the South.

However, in the early post-war years, Radical Republicans, many of them former abolitionists from northern states, set the agenda for African American equality and civil rights in Congress. Overriding a veto by President Johnson, Congress passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867. The act organized the ten remaining Confederate states into five military districts, each under the command of a U.S. general and ruled by military law, “to protect all persons in their rights of person and property [and] to suppress insurrection, disorder, and violence…”[xxiii] To achieve readmission to the Union and representation in Congress, the law specified that states had to ratify the 14th Amendment and approve a constitution giving the right to vote to all males 21 and older, including African American men who had resided in the state for at least a year.[xxiv] Reconstruction lasted until the election of 1877 when Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the presidency in a compromise that led to the removal of federal troops from all Southern states.[xxv]

Virginia avoided military governance throughout the full period of Reconstruction by fulfilling the requirements of the Reconstruction Act. The Commonwealth agreed to a new state constitution in 1869, granting suffrage to Black men.[xxvi] In that year, master carpenter George Seaton, born free in Alexandria in the 1820s, began his two-year term in the Virginia House of Delegates. On October 8, he voted for ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution as a requirement for Virginia’s readmission to the Union.[xxvii] The readmission date, January 26, 1870, marked the official end of federal rule and a return to civilian control in Alexandria and the rest of Virginia.[xxviii] As a result of the laws passed by the Radical Republican Congress, newly enfranchised Black men gained a voice in government in the 1870s for the first time in American history, winning election to southern state legislatures and to the U.S. Congress. In Alexandria, the 1871 elections resulted in the first African American members of the Common Council and the Board of Aldermen.[xxix]

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Disenfranchisement and Resurgence of Policies of White Supremacy

Punishment for marriage.—If any white person intermarry with a colored person, or any colored person intermarry with a white person, he shall be guilty of a felony and shall be punished by confinement in the penitentiary for not less than one nor more than five years.[xxix]

Virginia Racial Integrity Act, March 20, 1924

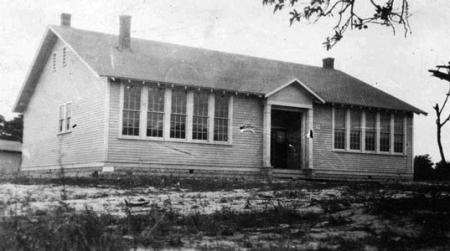

Source: Alexandria Black History Museum and Rosenwald Fund Archives at Fisk University

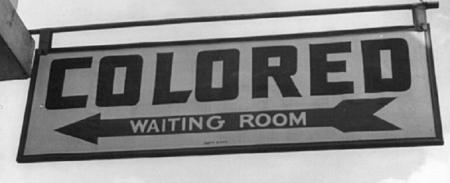

In less than a decade, however, a violent backlash reversed the changes brought about by the Constitutional Amendments and restored policies of white supremacy in the South. While federal law extended the benefits of citizenship to African American people, the legislatures of most southern states began to pass and implement ‘Black Codes,’ laws restricting their rights and freedom. Such laws made it illegal for African American people to vote, serve on juries, travel at will, marry whomever they chose, or work at any occupation they chose.[xxxi] In Virginia, an 1870 statute prohibited white and Black children from being taught in the same school. Following the state legislation, an 1871 Alexandria law instituted segregated schools, a separate but unequal educational system that would last nearly 100 years.[xxxii] Later that decade, the Virginia legislature passed its first of several miscegenation laws that stipulated prison sentences and fines for interracial marriage, statutes that also remained on the books for nearly a century.[xxxiii]

By the end of the nineteenth century and the turn of the twentieth century, racial segregation had become entrenched in the South. Southern states enforced a race-based system of political, economic, and social relationships through lynching and Jim Crow laws. The system denied the vote to African American men and sought to control Black populations through policies of terrorism and fear of imprisonment. Alexandria was no exception. To date, historians have documented two lynchings that took place on and near King and Cameron streets in the heart of the city with participation by mobs of from 500 to thousands of individuals: Joseph McCoy on April 23, 1897, and Benjamin Thomas on August 8, 1899.[xxxiv] As demonstrated by subsequent history through the twentieth century and beyond, emancipation was only the beginning of a long struggle for full equality and civil rights.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Footnotes

[i] W.E.B Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (New York: Barnes and Noble Classics, 2003), 17.

[ii] Julia A. Wilbur to Mrs. Amy Kirby Post, 5 November 1862, Family papers of Isaac and Amy Kirby Post, 1817-1918, Rush Rhees Library, The University of Rochester, New York.

[iii] Alexandria Gazette, 29 September 1862.

[iv] Alexandria Gazette, 31 October 1862.

[v] Alexandria Gazette, 18 July 1865.

[vi] Simon Cameron to Benjamin Butler, 30 May 1861; “The Fugitive Slaves in Federal Camps, Instruction of the War Department to Gen. Butler,” reprinted in Boston Evening Transcript, 31 May 1861, 2.

[vii] Benjamin Franklin Butler, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscence of Major-General Benjamin F. Butler: Butler’s Book (Boston, MA: A.M. Thayer and Co., 1892), 259.

[viii] Benjamin Franklin Butler, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscence of Major-General Benjamin F. Butler: Butler’s Book (Boston, MA: A.M. Thayer and Co., 1892), 259.

[ix] Camden Democrat, 15 June 1861, 3.

[x] Quoted in Adam Goodheart, “How Slavery Really Ended in America.” The New York Time Magazine, 1 April 2011.

[xi] The Local News, Alexandria, VA, 22 October 1861, 2.

[xii] An Act to Confiscate Property used for Insurrectionary Purposes, August 6, 1861, U.S. Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America, vol. 12 (Boston, MA: Little Brown and Company, 1863), 319.

[xiii] An Act to suppress Insurrection, to punish Treason and Rebellion, to seize and confiscate the Property of Rebels, and for other Purposes, 17 July 1862, U.S. Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America, vol. 12 (Boston, MA: Little Brown and Company, 1863), 589-592.

[xiv] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 31 December 1862, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/JuliaWilburDiary1860to1866.pdf.

[xv] Emancipation Proclamation, 1 January 1863, Presidential Proclamations, 1791-1991, Record Group 11, General Records of the United States Government, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

[xvi] Harold Holzer, Edna Greene Medford, and Frank J. Williams, The Emancipation Proclamation: Three Views (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2006), 17.

[xvii] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 1 January 1863, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/JuliaWilburDiary1860to1866.pdf.

[xviii] Alexandria Gazette, 31 December 1863.

[xix] U.S. Constitution, Thirteenth Amendment - Slavery And Involuntary Servitude, https://constitution.findlaw.com/amendment13.html; Fourteenth Amendment - Rights Guaranteed Privileges and Immunities of Citizenship, Due Process and Equal Protection, https://constitution.findlaw.com/amendment14.html; Fifteenth Amendment - Right of Citizens to Vote, https://constitution.findlaw.com/amendment15.html.

[xx] “The First Colored Senator. Speech in the Senate, on the Admission of Hon. Hiram R. Revels, A Colored Person, As Senator of Mississippi, February 25, 1870,” Charles Sumner: His Complete Works, Vol. 18 (Norwood, Massachusetts: Norwood Press, 1900), 6-9; cited in Reconstruction in America, Racial Violence after the Civil War, 1865-1876, Equal Justice Institute, https://eji.org/report/reconstruction-in-america/freedom-to-fear/#test-subchapter

[xxi] Julia A. Wilbur, Personal Diary, 1844-1894, 16 April 1865, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College Libraries, Pennsylvania, transcription at https://www.alexandriava.gov/uploadedFiles/historic/info/civilwar/JuliaWilburDiary1860to1866.pdf.

[xxii] Pardons by the President, H. Exec Doc 16, Serial Set Vol. No. 1330, 4 December 1867, 88, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C

[xxiii] https://loveman.sdsu.edu/docs/1867FirstReconstructionAct.pdf.

[xxiv] https://loveman.sdsu.edu/docs/1867FirstReconstructionAct.pdf, https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Historical-Essays/Fifteenth-Amendment/Reconstruction/.

[xxv] Sarah Pruitt, https://www.history.com/news/reconstruction-1876-election-rutherford-hayes

[xxvi] Reconstruction, Library of Virginia, Public Resources, Manuscript Collection, Richmond, VA, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/Civil-War/Reconstruction.htm.

[xxvii] “George Louis Seaton (Ca. 1822 – 1881)” Encyclopedia Virginia, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Seaton_George_Lewis_ca_1822-1881#start_entry; George Lewis Seaton House National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 2001, Virginia Department of Historic Resources website, https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/100-5015-0007_George_Lewis_Seaton_House_2004_Final_Nomination.pdf.

[xxviii] Reconstruction, Library of Virginia, Public Resources, Manuscript Collection, Richmond, VA, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/Civil-War/Reconstruction.htm..

[xxix] “Discovering the Decades, 1860s,” Al Cox, Pamela J. Cressey, Timothy J. Dennée, T. Michael Miller, and Peter Smith, City of Alexandria, VA website, https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/the-history-of-alexandria-discovering-the-decades.

[xxx] Virginia Racial Integrity Act, March 20, 1924, Virginia Code Section 20-59, https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/eugenics-race-and-marriage

[xxxi] “The Southern “Black Codes of 1865-66,” Constitutional Rights Foundation, https://www.crf-usa.org/brown-v-board-50th-anniversary/southern-black-codes.html.

[xxxii] “Integrating Alexandria,” The Connection Newspapers,, 22 February 2006, www.connectionnewspapers.com/news/2006/feb/22/integrating-alexandria/.

[xxxiii] Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), http://uscivilliberties.org/historical-overview/4158-miscegenation-laws.html.

[xxxiv] Amy Bertsch, “Lynchings in Alexandria,” PowerPoint presentation, on file Alexandria Black History Museum, Alexandria, VA.