African American Heritage Trail - South Waterfront Route (stops 1-10)

South Waterfront Route

African American Heritage Trail

South Waterfront Route

Stops 1-10 from the Foot of King Street

Stops 11-19 from Windmill Hill Park to Jones Point Park

The North Waterfront Route and future segments can be viewed by clicking the button below.

African American Heritage Trails (Main Page)

We envision the African American Heritage Trail as consisting of several interconnecting routes across the City of Alexandria. Together, these trails illuminate the history of the African American community over a span of several centuries. This trail highlights the contributions of Black Alexandrians, free and enslaved, to the history of Alexandria’s waterfront. We strive to forefront their experiences while recognizing that their voices are often not directly preserved in the historical record.

The South Trail Route is the second in a series of trails covering the waterfront. The African American Heritage Trail Committee created this walking tour, with the support of the Office of Historic Alexandria.

This relatively flat walk takes you along the waterfront from the foot of King Street to Jones Point, a little over two miles in distance. The trail mostly follows level, paved surfaces, but there are some areas of moderate slope, gravel paths, and stairs. Included are alternate paths. The walking tour should take about an hour and a half at a leisurely pace. The walk back from the end of the trail is a little more than a mile, so plan accordingly or arrange for transportation from Jones Point.

Even before the founding of the City of Alexandria in 1749, Africans and their descendants, enslaved and free, have lived and worked along the waterfront, making significant contributions to the local economy and culture. In the 1820s and 1830s, Alexandria became home to the largest domestic slave trading firm, which specialized in the sale and trafficking of enslaved African Americans from the Chesapeake to the Deep South. The Civil War revolutionized social and economic relations, and newly freed African Americans found new job opportunities as a result of the waterfront’s industrialization. The Potomac River played an important role in leisure activities too, including picnicking, boating, and fishing, much as it does for Alexandrians and visitors today.

Thank you to members of the African American Heritage Trail Committee past and present: Councilman John Chapman, Susan Cohen, Gwen Day-Fuller, Indy McCall, Maddy McCoy, Krystyn Moon (Chair), McArthur Myers, and Ted Pulliam. The Office of Historic Alexandria support provided by staff of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum and Alexandria Black History Museum.

The StoryMap

Alexandria’s African American history is told through an online StoryMap and can be experienced in-home on your computer or on your smartphone as you walk the trail along the Potomac River. This relatively flat walk takes you along the waterfront from the foot of King Street to Jones Point, a little over two miles in distance. The trail mostly follows level, paved surfaces, but there are some areas of moderate slope, gravel paths, and stairs. Included are alternate paths. The walking tour should take about 90 minutes at a leisurely pace. The walk back from the end of the trail is a little more than a mile, so plan accordingly or arrange for transportation from Jones Point.

This webpage presents more in-depth information about the stops highlighted in the StoryMap.

Stop 1: Enslaved on the Waterfront

Foot of King Street

Trail Sign: Foot of King Street

18th century

Alexandria was founded in 1749 as a tobacco port town built with the labor of untold numbers of enslaved and free Black people. The growth of mercantile activities in the late 18th century led to the filling in of the original crescent-shaped bay, physically changing the landscape of the waterfront. This land making project enabled the wharves to better reach the shipping channels farther out in the Potomac River. Turning west and looking up King Street, you can see a slight rise where the steep banks of the original shoreline stood before the filling of the bay. The entire area around lower King Street east of Lee Street (formerly called Water Street) sits on the new land made by early Alexandrians.

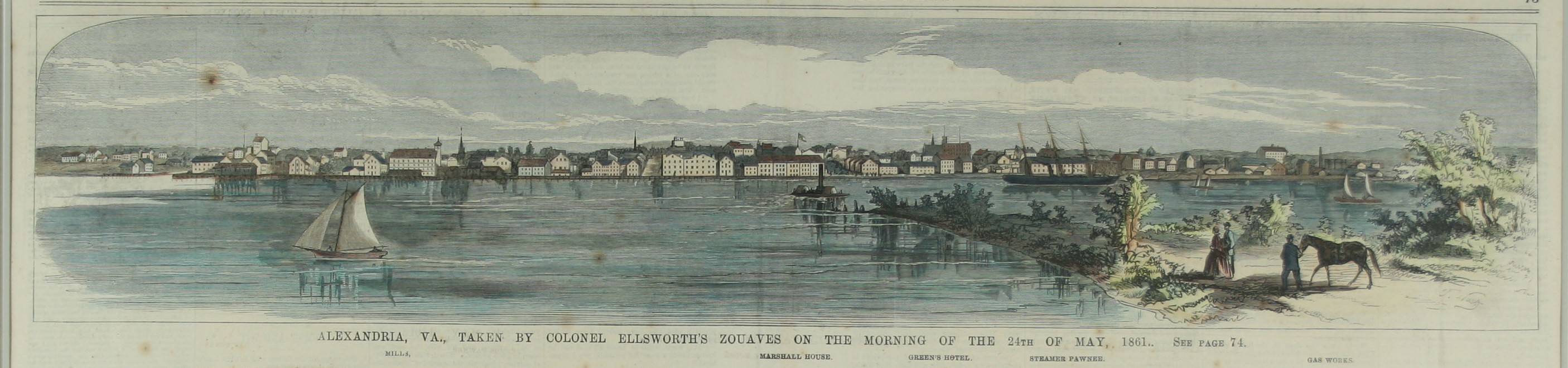

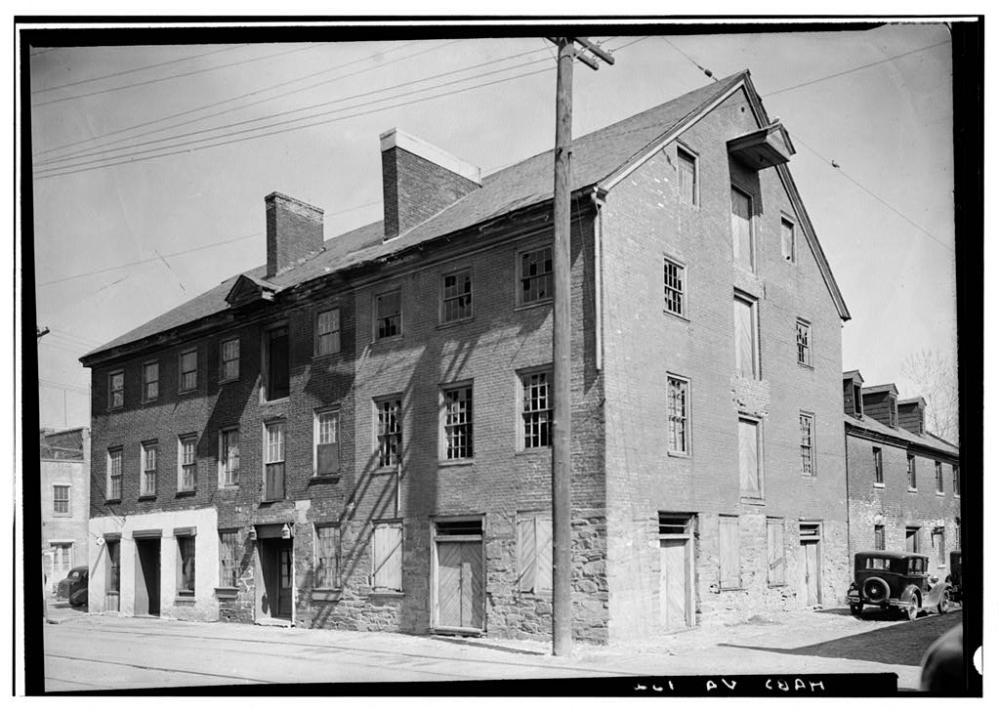

Standing at the “Foot of King Street” sign, you face west towards the intersection of King and South Union Street. At the southeast corner of this intersection stands a warehouse where enslaved Africans and African Americans likely worked for John Fitzgerald, a prosperous merchant and Revolutionary War colonel.[1] Capturing the everyday lives of Alexandria’s enslaved population on the waterfront is difficult; however, documents, such as Virginia’s “Free Negro Registers,” a list of individuals whose free status was verified, provide a glimpse. Born around 1730, Anthony Blew was an enslaved hostler and groom, caring for Fitzgerald’s horses.[2] In the 1780s and 1790s, Fitzgerald owned around six horses, used for riding and possibly hauling goods from his warehouse to stores along King Street. Sometime before his death in 1799, Fitzgerald freed Blew, which his widow, Jane, verified two years later in an affidavit.[3] In 1801, Blew obtained a certificate that proved his free status. Unfortunately, nothing else is known about Blew at this time.

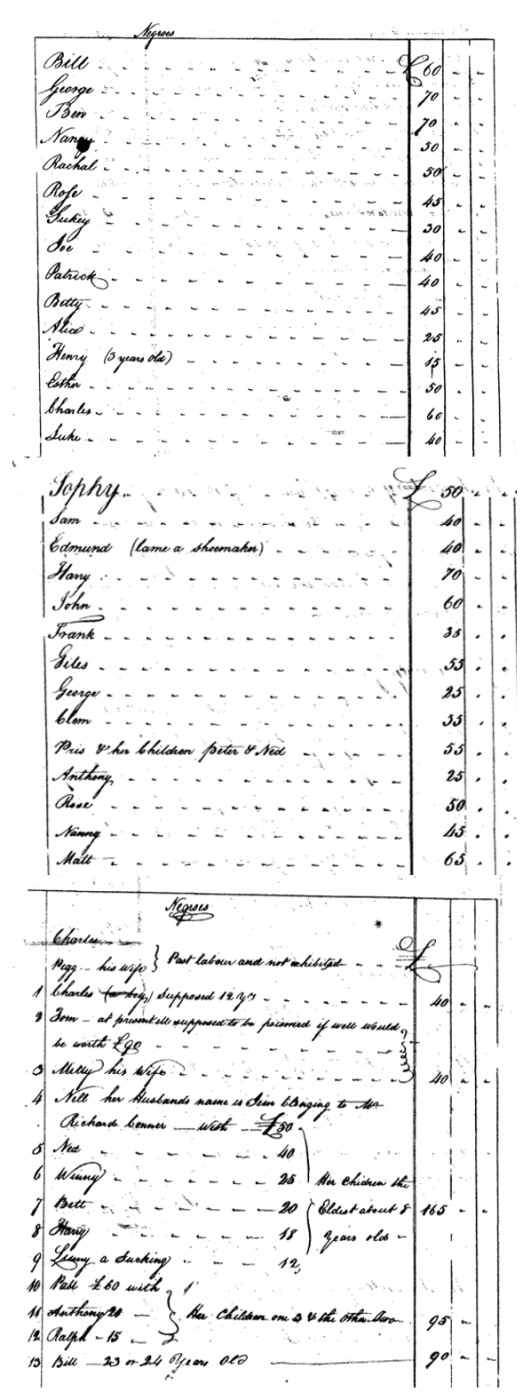

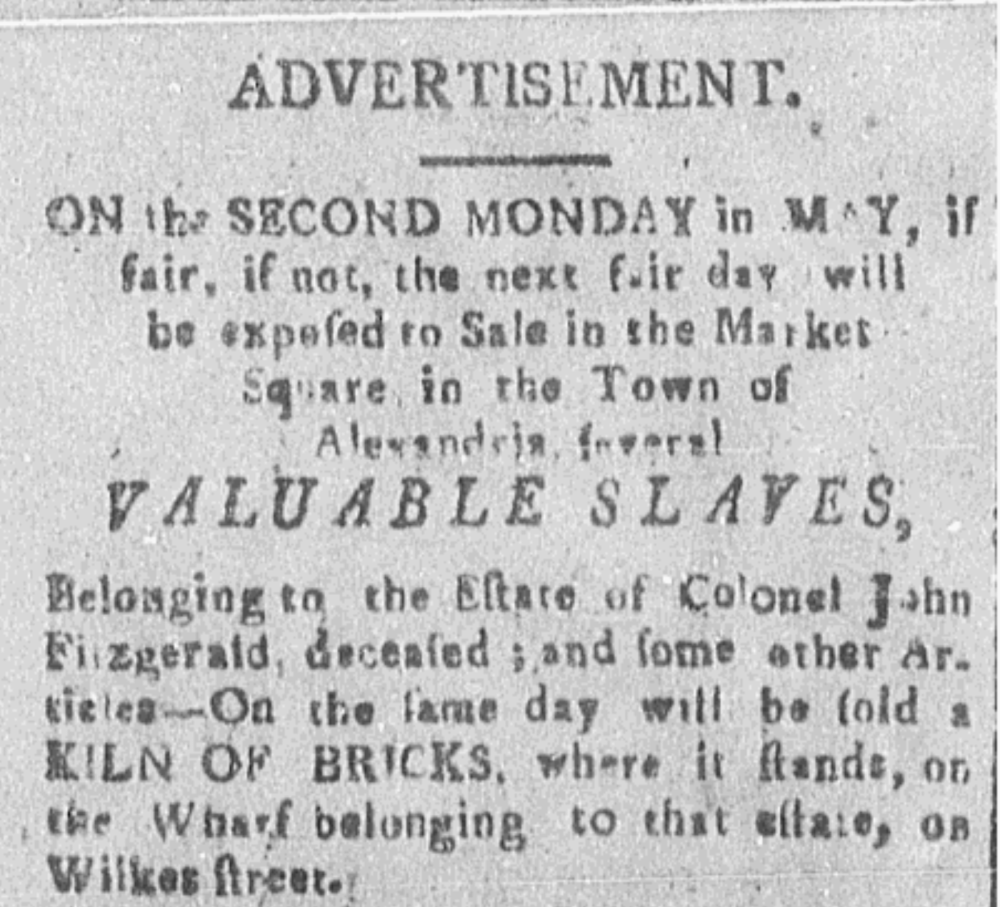

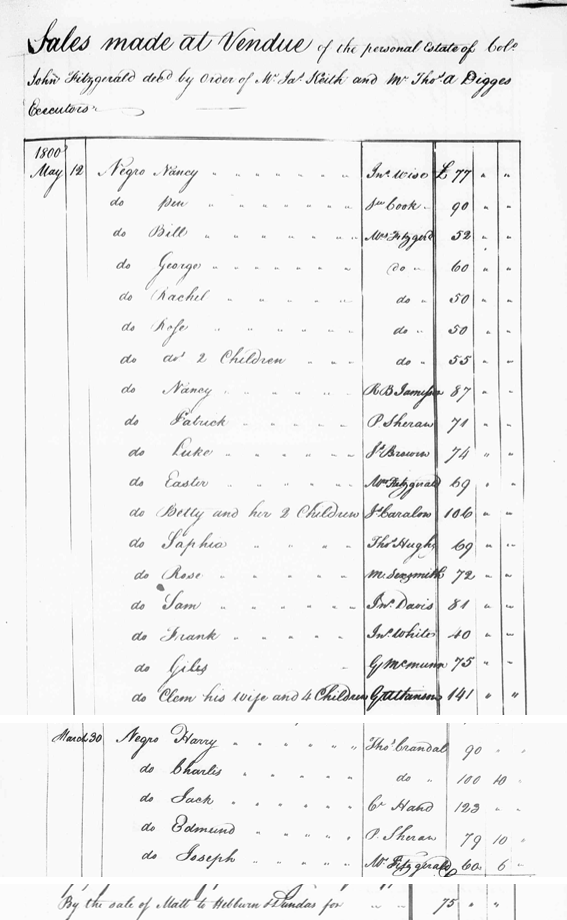

Not all people enslaved to Fitzgerald obtained their freedom. At the time of his death in 1799, Fitzgerald enslaved 46 people as documented in his probate inventory. Many of these people resided and worked on the waterfront, as captured in Fitzgerald’s personal property tax records from 1782 until his death. Annually, Fitzgerald was taxed for 10 to 14 enslaved individuals, though this number is likely an undercount because enslavers were not taxed for children under the age of 12.[4]

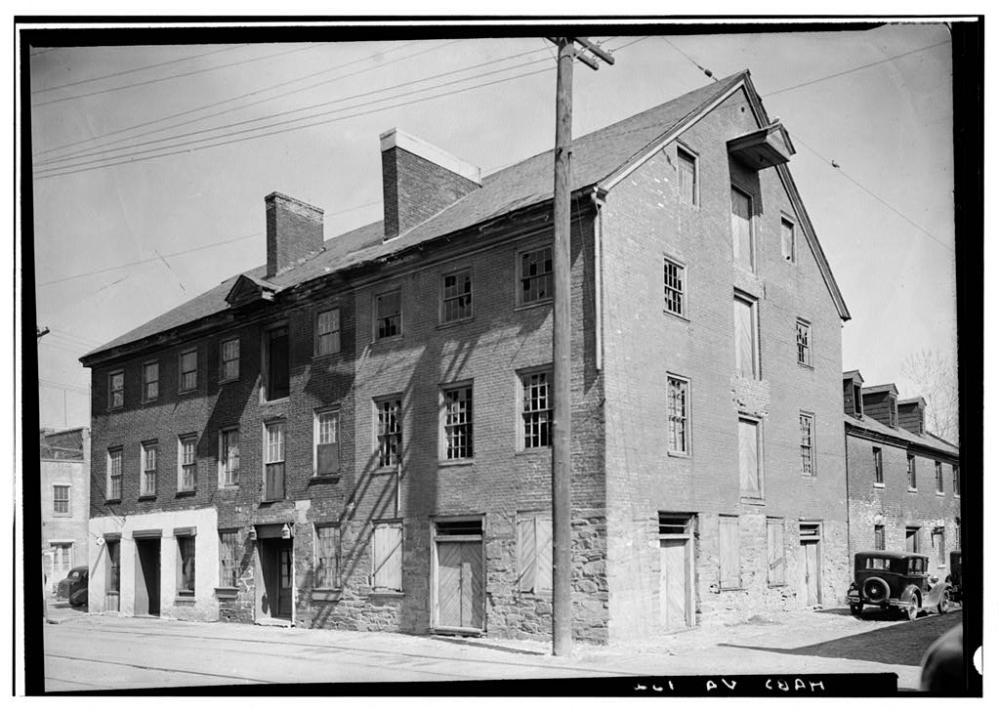

The death of a slaveholder often meant separation and dispersal of an enslaved community through the settlement of estates and inheritance. Based on Maddy McCoy’s research, we know something of what happened to the enslaved people owned by Fitzgerald in the years after his death.[5] This advertisement announced the auction at Market Square of Fitzgerald’s estate, including the rental of his warehouse and the sale of household items and enslaved people, referring to them as “valuable slaves.”[6]

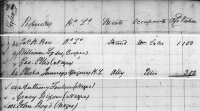

It appears that, as a result of this auction in May 1800, 12 different men and women bought over half of the enslaved people owned by Fitzgerald.

- Bill, George, Rachel, Esther, Rose, and Rose’s two children, purchased by Jane Fitzgerald, John Fitzgerald’s wife

- Nancy, purchased by John Wise

- Patrick, purchased by P. Sheran

- Betty and her two children, purchased by James Caralon

- Luke, purchased by James Brown

- Sophia, purchased by Thomas Hughs

- Sam, purchased by John Davies

- Frank, purchased by Jonathan White

- Giles, purchased by G. McMunn

- Clem, his wife, and their four children, purchased by G. Atkinson

- A second woman named Rose, purchased by M. Sexsmith

- A second woman named Nancy, purchased by R. B. Jamesson

The Fitzgerald estate continued to sell members of the enslaved community in addition to those sold at the Market Square auction.

- Joseph, purchased by Jane Fitzgerald

- Edmund, purchased by P. Sheran

- Charles and Harry, purchased by Thomas Crandal

- Matt, purchased by Hepburn and Dundas

The estate accounts do not record the fates of the remaining enslaved people originally owned by Fitzgerald.[7] This event highlights the tenuousness and uncertainty of life for enslaved people in Alexandria and throughout the south.

Stop 1: Footnotes

[1] Diane Riker, “Fitzgerald’s Warehouse King and Union Streets” (Alexandria, VA: Studies of the Old Waterfront, Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria Archaeology, 2008), accessed February 7, 2022,

[2] Patricia B. Duncan (comp.), Fairfax County, Virginia Personal Property Tax Lists, 1782-1850 (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2021).

[3] Anthony Blew, Free Negro Register, 1801, Arlington County (Va.) Free Negro and Slave Records, 1788-1866; Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, accessed March 11, 2022.

[4] Maddy McCoy, Slave Inventory Database, to Mark B. Jinks, City Manager, September 28, 2018, accessed February 7, 2022.

[5] McCoy, 2018.

[6] [Advertisement], District of Columbia Daily Advertiser May 8, 1800.

[7] McCoy, 2018.

Stop 2: The Domestic Slave Trade in Alexandria

Waterfront Park

Trail Sign: The Domestic Slave Trade

19th Century

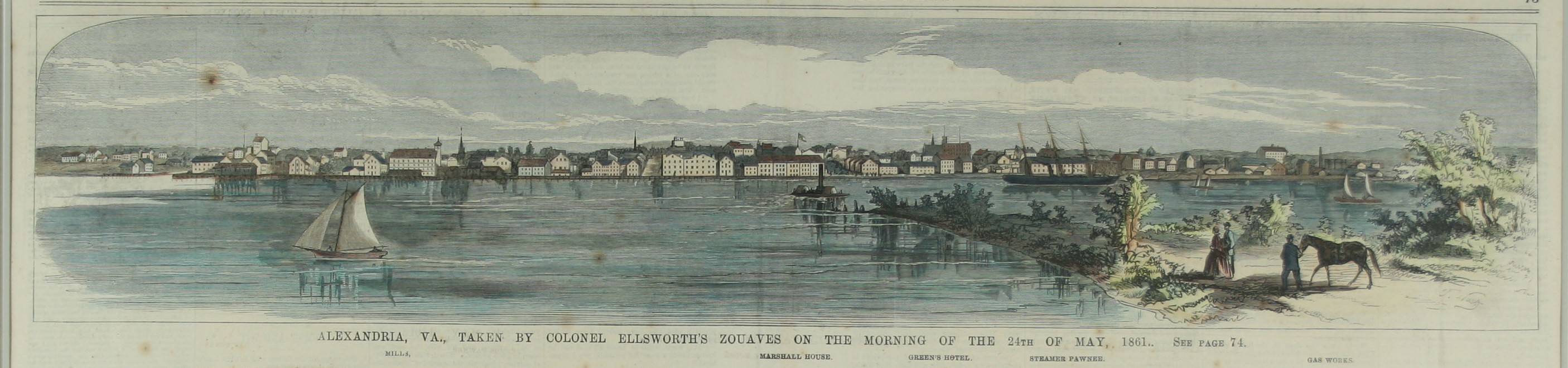

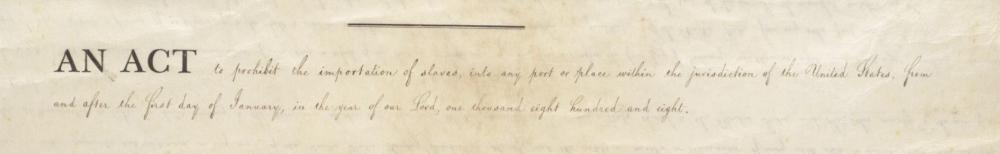

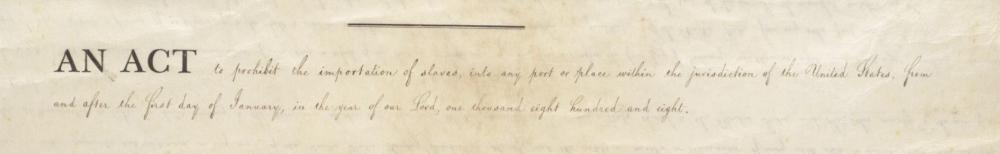

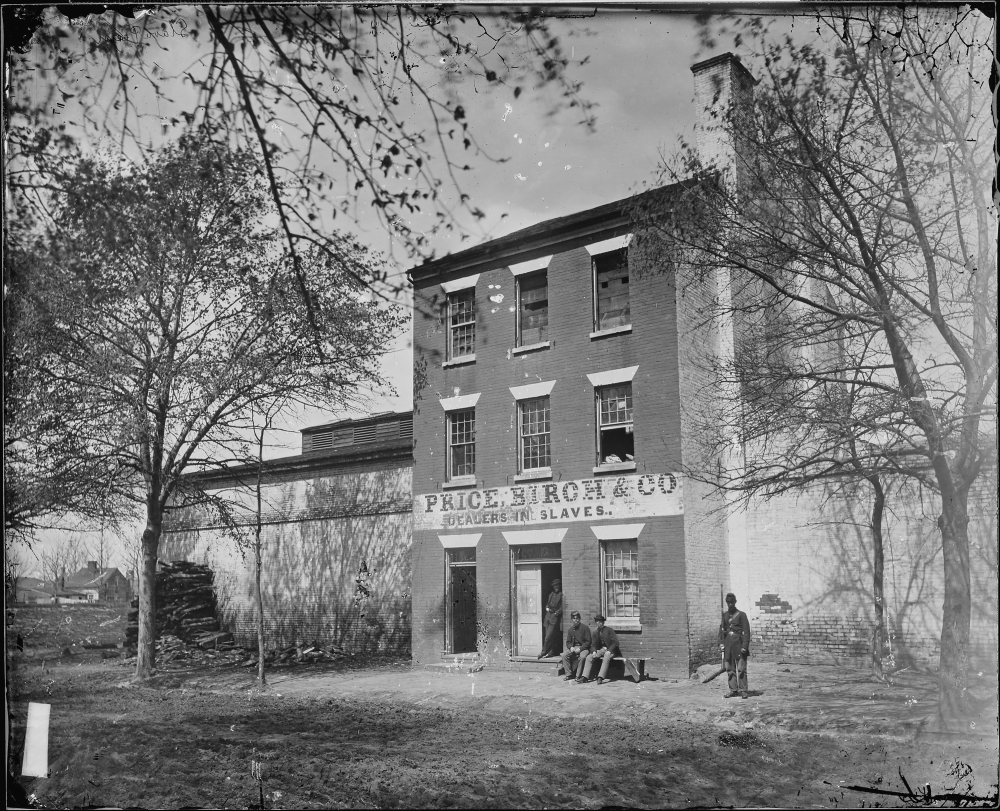

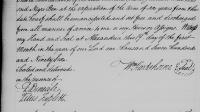

On January 1, 1808, the earliest date allowed by the U.S. Constitution, the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves went into effect and stated, “it shall not be lawful to import or bring into the United States… any negro, mulatto, or person of colour… as a slave.”[1] Passed by Congress the previous year, the act banned U.S. citizens from participating in the international slave trade. While importing enslaved Africans was now illegal, selling and transporting enslaved people within the borders of the United States was not.[2] As a result, Alexandria became one of the largest centers of the domestic slave trade in the country in the 1820s and 1830s.[3]

Throughout the early 19th century, slave traders forcibly transported hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans and African Americans from the Chesapeake region to the Deep South.[4] Depleted soils and a shift from tobacco to less labor-intensive grain-based agriculture in the Chesapeake along with westward expansion into the cotton and sugar-producing areas of the Deep South fueled this forced migration.[5]

Slaveholders forcibly relocated some enslaved people to these new regions, but established slave traders and slave trading firms trafficked many others.[6] These companies purchased or consigned enslaved people and transported them by ship from ports such as Alexandria, Richmond, Norfolk, and Baltimore to destinations like New Orleans, Charleston, Savannah, and Mobile.[7] Those not trafficked by sea were chained together in coffles and made to walk hundreds of miles to depots to the south and west, like the one at the Forks of the Road outside Natchez, Mississippi.[8]

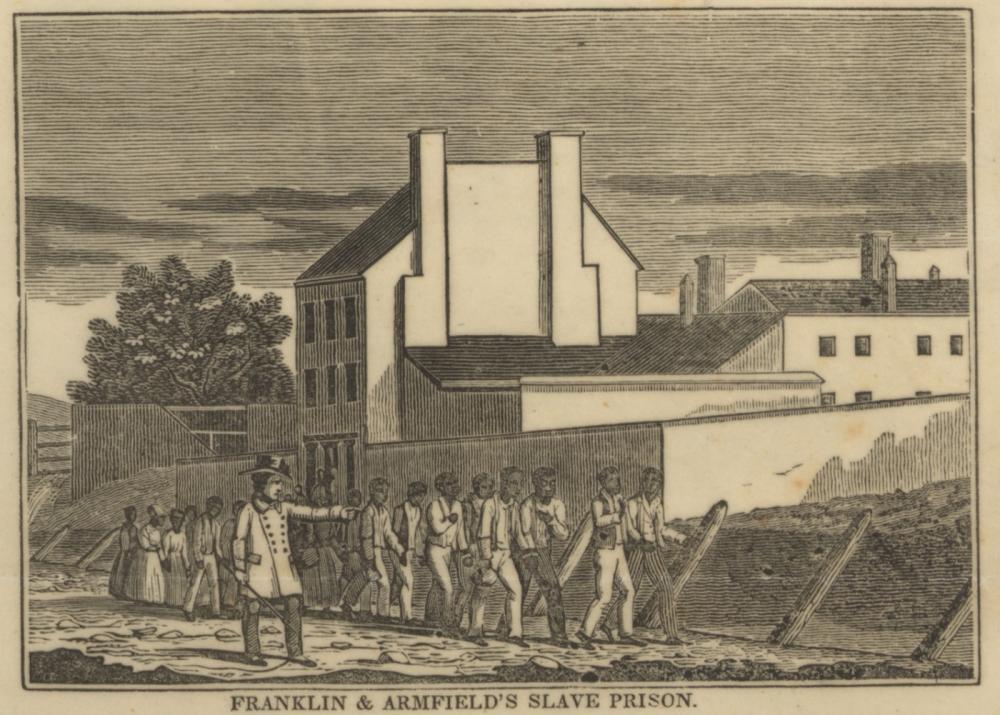

In February 1828, Isaac Franklin of Sumner County, Tennessee, and John Armfield of Guilford County, North Carolina, formed the slave trading firm of Franklin & Armfield and soon after leased a large, brick house on upper Duke Street. From its headquarters and jail at 1315 Duke Street, Franklin & Armfield quickly became one of the country’s largest and most notorious slave trading firms.[9]

Based in Alexandria, Franklin & Armfield partnered with other slave traders in cities and towns across the Chesapeake region, from the Blue Ridge Mountains to the Eastern Shore, from Baltimore to Richmond. In the summer months, the firm transported people overland to Natchez, Mississippi where the firm had another facility. Throughout the rest of the year, the firm operated a regular packet service to New Orleans, with a ship departing Alexandria as often as every two weeks. People held captive less than a mile away at 1315 Duke Street were brought to the waterfront where they boarded ships like the Uncas, Tribune, and Isaac Franklin. Once onboard, it took about a month to reach New Orleans, where the firm had yet another jail.[10]

After the firm of Franklin & Armfield ended their operations in Alexandria in February 1837, a series of slave traders used the slave jail complex until May 24, 1861. On that morning, the day after Virginia voted to secede from the United States, the Union Army crossed the bridges over the Potomac River and landed by steamboat on Alexandria’s wharves. The Union Army occupied (or liberated) Alexandria for the duration of the American Civil War.

1315 Duke Street is now the home of a museum of the domestic slave trade and is operated by the Office of Historic Alexandria.[11]

Stop 2: Footnotes

[1] The relevant text of Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution reads: “The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.” See An Act to Prohibit the Importation of Slaves…, Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History, and Diplomacy, accessed December 16, 2021.

[2] Michael A. Ridgeway, “A Peculiar Business: Slave Trading in Alexandria, Virginia, 1825-1861” (master’s thesis, Georgetown University, 1976), 4-5.

[3] Ridgeway, ii-iv, 14-30; Bancroft, 45, 58-61.

[4] Jennie, K. Williams, “Oceans of Kinfolk: The Coastwise Traffic of Enslaved People to New Orleans, 1820-1860” (PhD diss., Johns Hopkins University, 2020), 8-9.

[5] Williams, 10-11; Tomoku Yagyu, “Slave Traders and Planters in the Expanding South: Entrepreneurial Strategies, Business Networks, and Western Migration in the Atlantic World, 1787-1859” (PhD diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2006), 67-68; Robert Harold Gudmestad, “A Troublesome Commerce: The Interstate Slave Trade, 1808-1840” (PhD diss., Louisiana State University, 1999), 12-14; Ridgeway, 5-12.

[6] Edward Ball, “Retracing Slavery's Trail of Tears: America's Forgotten Migration–The Journeys of a Million African-Americans from the Tobacco South to the Cotton South,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2015, accessed December 15, 2021; Mary Kathryn Menck, "The Devil's Backbone: Race, Space, and Nation-Building on the Natchez Trace" (PhD diss., Tufts University, 2017), 26-34; Williams, 19.

[7] Williams, 19.

[8] Ball, “Retracing Slavery's Trail of Tears.”

[9] For a detailed history of this property, see Benjamin A. Skolnik, “Building and Property History: 1315 Duke Street, Alexandria, Virginia” (Alexandria: Alexandria Archaeology, 2021), accessed December 15, 2021; Janice G. Artemel, Elizabeth A. Crowell, and Jeff Parker, “The Alexandria Slave Pen: The Archaeology of Urban Captivity” (Washington, D.C.: Engineering-Science, Inc., 1987). See also Frederic Bancroft, Slave Trading in the Old South (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. 1931), 60-66; Ridgeway, 50-86; Calvin Schermerhorn, The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 1815-1860 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 124-168.

[10] Joshua D. Rothman, The Ledger and the Chain: How Domestic Slave Traders Shaped America (New York: Basic Books, 2021), 211-212, 251-254; Ball, “Retracing Slavery's Trail of Tears.”

[11] “Freedom House Museum,” City of Alexandria, Virginia, accessed December 15, 2021.

Stop 3: George Henry, Enslaved Ship Captain

Waterfront Park, Riverside

Trail Sign: George Henry, Enslaved Ship Captain

19th Century

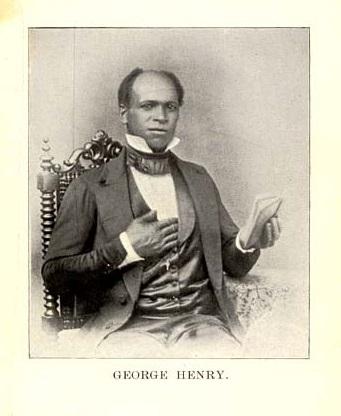

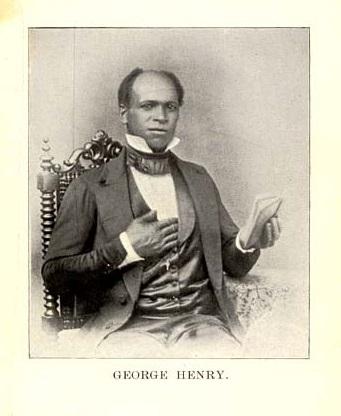

Published in 1894, The Life of George Henry Together with a Brief History of the Colored People in America captures the personal experiences of the author in his own words. George Henry described himself as the enslaved captain of the schooner Llewelyn, which was partially owned by Alexandrian Sally W. Griffith. Henry’s account, written almost 50 years after his enslavement, provides few dates and is not without conflicting details, but includes a unique perspective to the Chesapeake’s waterways in the antebellum period.

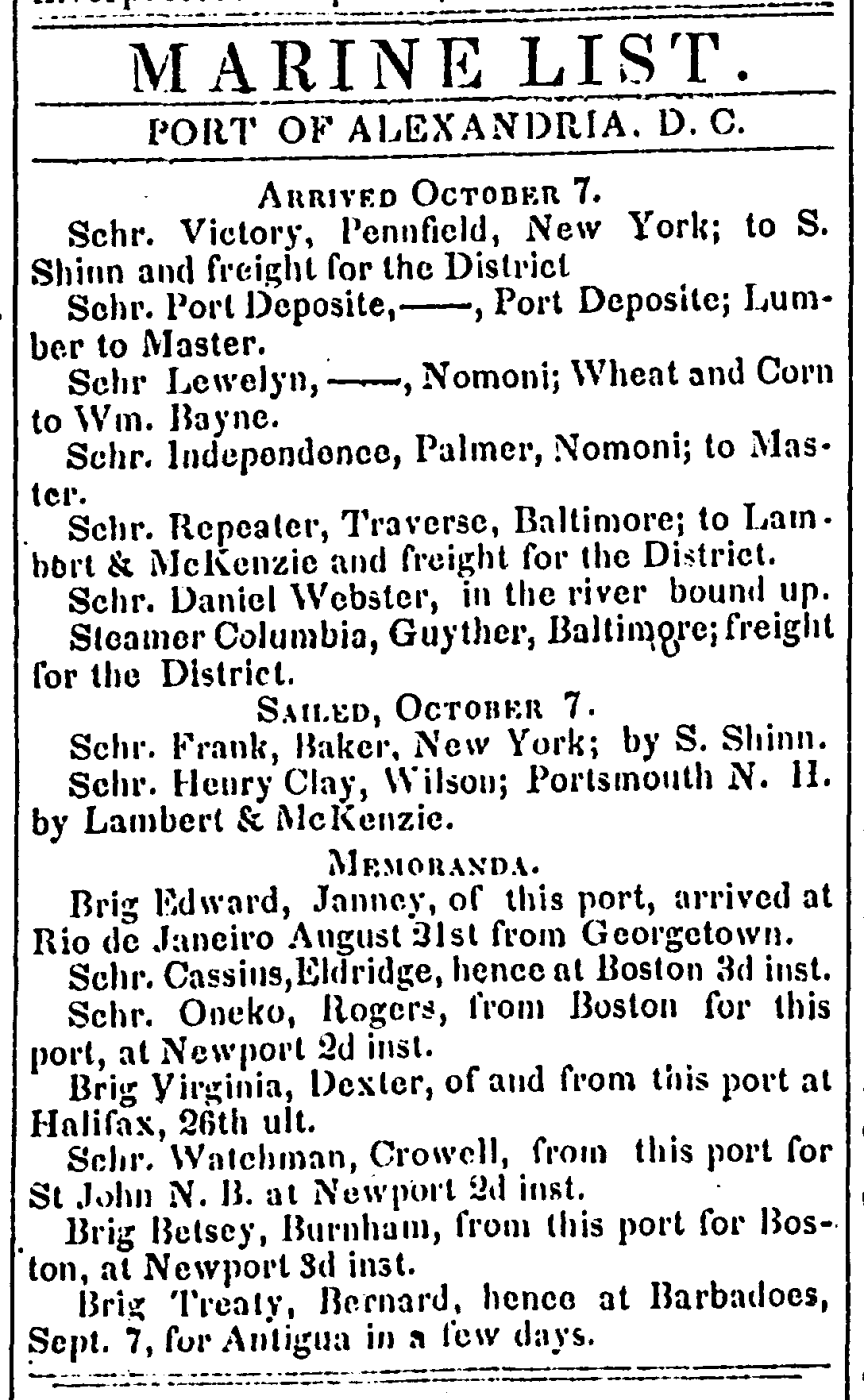

The Llewelyn periodically unloaded lumber and agricultural products here in Alexandria. Henry was not listed as the captain of the Llewelyn in the Alexandria Gazette’s columns that were devoted to ship news, perhaps to avoid publicizing that African Americans worked in positions other than cooks, stewards, and seamen.[1] By the late 1830s or early 1840s, Henry and his crew of five transported timber, bark, logs, and grain to Baltimore, Annapolis, Alexandria, and other ports around the Chesapeake Bay.[2] He also cut wood on the Northern Neck of Virginia and delivered oak piles used to build the Alexandria Canal’s aqueduct that ran across the Potomac River at Georgetown.[3] In his memoir, Henry described an unusual amount of freedom for someone enslaved in pre-Civil War Virginia through his work on the water. He later recalled that he “was determined to let them [white slave holders] see that though black, I was a man in every sense of the word.”[4]

Sometime around the mid-1840s, however, an incident occurred that changed Henry’s mind about continuing to be an enslaved ship captain for Sally Griffin. As he wrote in his memoir, he had been “making money for her, just the same as if you were shaking it off a tree.” Yet “I went up one day in a hurry to pay her the money [proceeds from sale of the ship’s cargo], and she knocked my hat off.” Apparently, in his hurry he failed to be what Sally Griffin considered properly respectful. Henry continued, “I declared by all the Gods in creation that she should never take another cent out of my hands.”[5]

On his next trip to Baltimore, he docked his schooner loaded with grain as usual. Then, instead of waiting for the grain to be sold and pocketing the proceeds with him on his escape, he simply left the boat, grain, and crewmen at the dock, taking with him only what belonged to him: “one suit of clothes and fifty cents in his pocket.”[6]

About the next phase of his journey, he only wrote: “I traveled on till I got to Havre de Grace,” a small Maryland port town located where the Susquehanna River enters the Chesapeake Bay near the Bay’s head. From there he “paid a boy fifty cents to run me across to the Pennsylvania side.” Once he landed, he took the railroad and another short boat ride and arrived in Philadelphia where he found himself “with the wide world before me, [now only] to look out for myself as any other free man.”[7]

In addition to documenting the everyday life of an enslaved mariner, Henry’s text provides a glimpse into the domestic slave trade in and near Alexandria. Early in his sailing career, he recalled walking down a street in Washington, D.C. with a friend when he heard “such screaming and crying, we couldn’t tell what it meant, so we kept on till we met about two hundred men and women chained together, two and two.... [T]he scene was enough to bring tears into any man’s eyes if he had a heart.” He was told that these people were “being taken down to Alexandria to one of [John] Armfield’s vessels.”[8] Armfield was one of the country’s most notorious and prolific slave traders and operated out of Alexandria between 1828 and 1837. In his book, Henry noted that on later trips up the Potomac, he passed “more times than I have got fingers and toes” Franklin & Armfield’s ships as they left Alexandria for New Orleans loaded with enslaved African Americans. From time to time, he also found himself in the unsettling position of “unloading wood on one side of the wharf when [a Franklin & Armfield] vessel [was] loading slaves on the other side of the wharf.”[9] From Henry’s account, it is not clear if Armfield still owned these ships at the time Henry saw them, as they had been sold to other slave traders in 1836 and 1837, but the slave trader’s connection to these ships lingered. Henry’s memoir provides a rare glimpse not only into the experiences of enslaved seafarers on the Chesapeake in his own words, but also Alexandria’s role in the internal slave trade.

Stop 3: Footnotes

[1] W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 176.

[2] “A Plan of the Town of Alexandria, D.C. with the Environs” (Philadelphia: Lith. of T. Sinclair, 1845), accessed December 15, 2021; George Henry, The Life of George Henry Together with a Brief History of the Colored People in America (Providence, R.I.: H. I. Gould & Co., Printers, 1894), 37, accessed October 20, 2009. In the mid-1840s, the Alexandria Gazette reported that the Lewellyn brought goods to Stephen Shinn, who was located on Janney’s Wharf. “Alexandria Marine List,” Alexandria Gazette November 19, 1843, November 17, 1845, and December 25, 1846; [Advertisements], Alexandria Gazette April 12, 1843, February 11, 1846, and June 15, 1846. For other information in this paragraph, see Henry, 22-23.

[3] Henry, 23.

[4] Henry, 23.

[5] Henry, 37.

[6] Henry, 38, 44.

[7] Henry, 45.

[8] Henry, 17.

[9] Henry, 40.

Stop 4: The River Queen

Foot of Prince Street

Trail Sign: The River Queen

20th Century

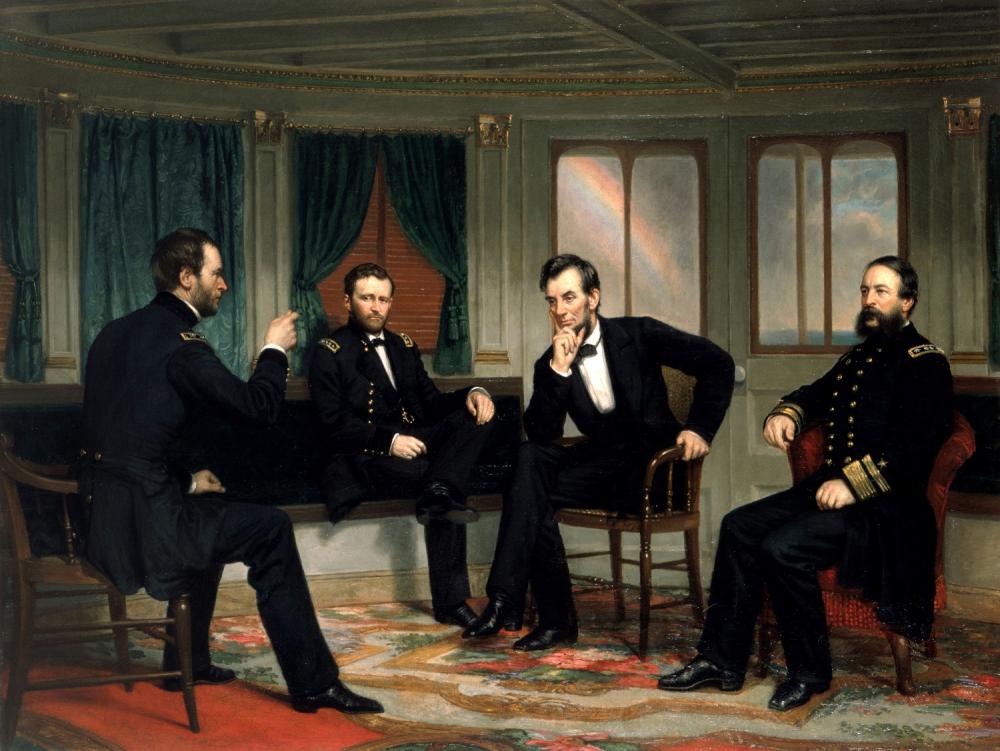

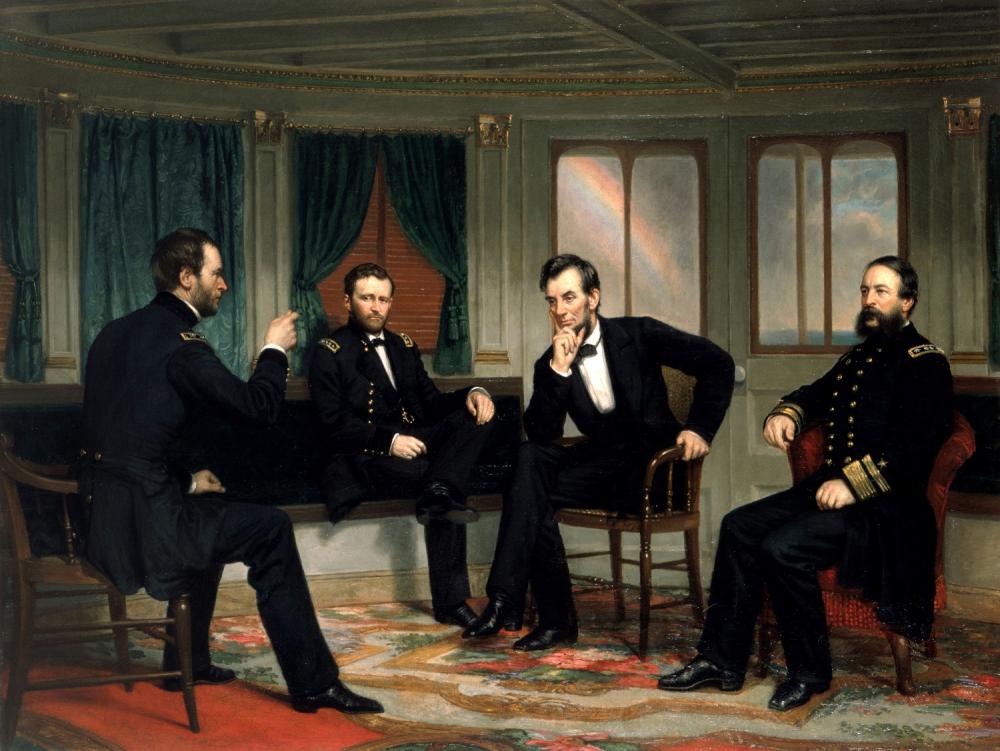

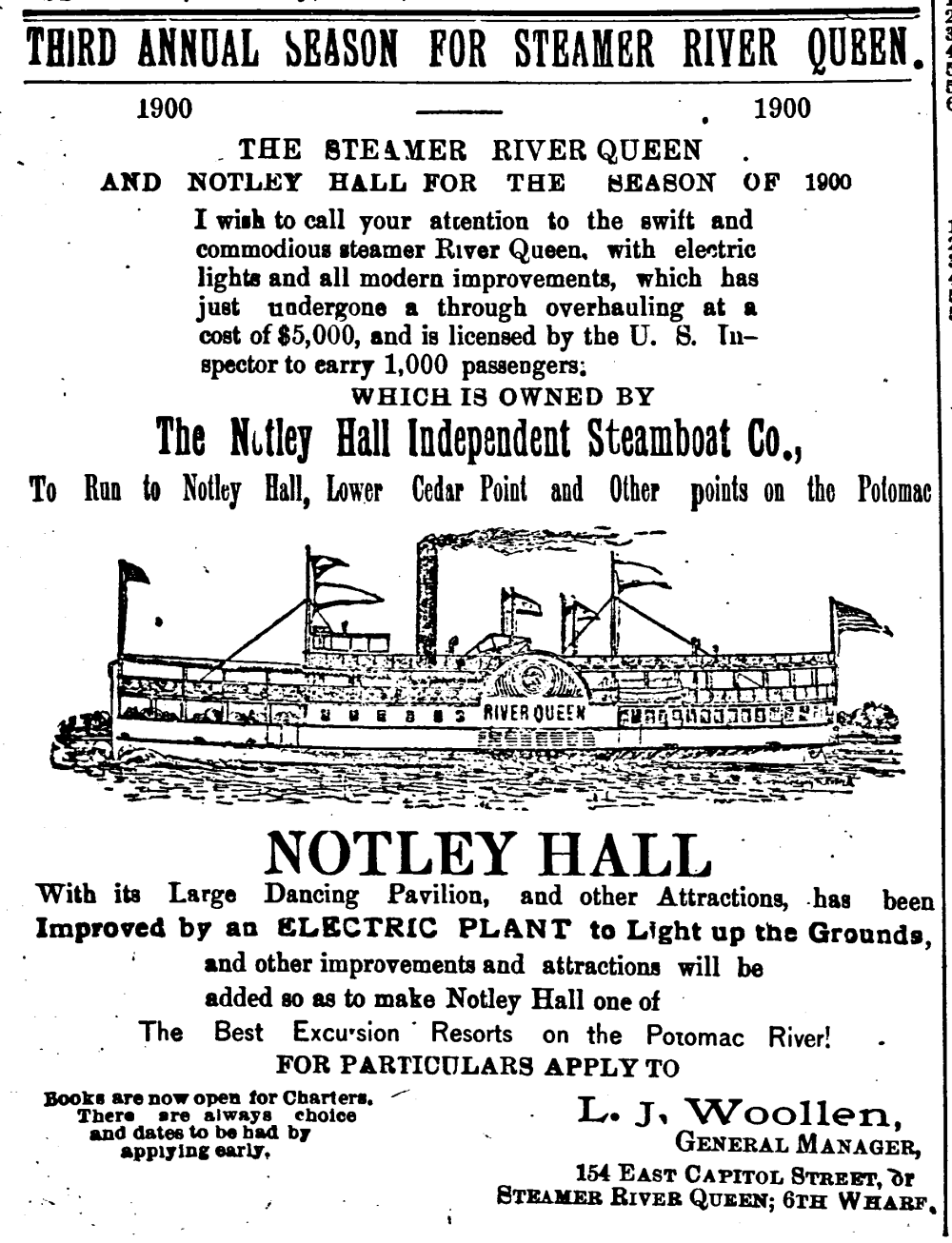

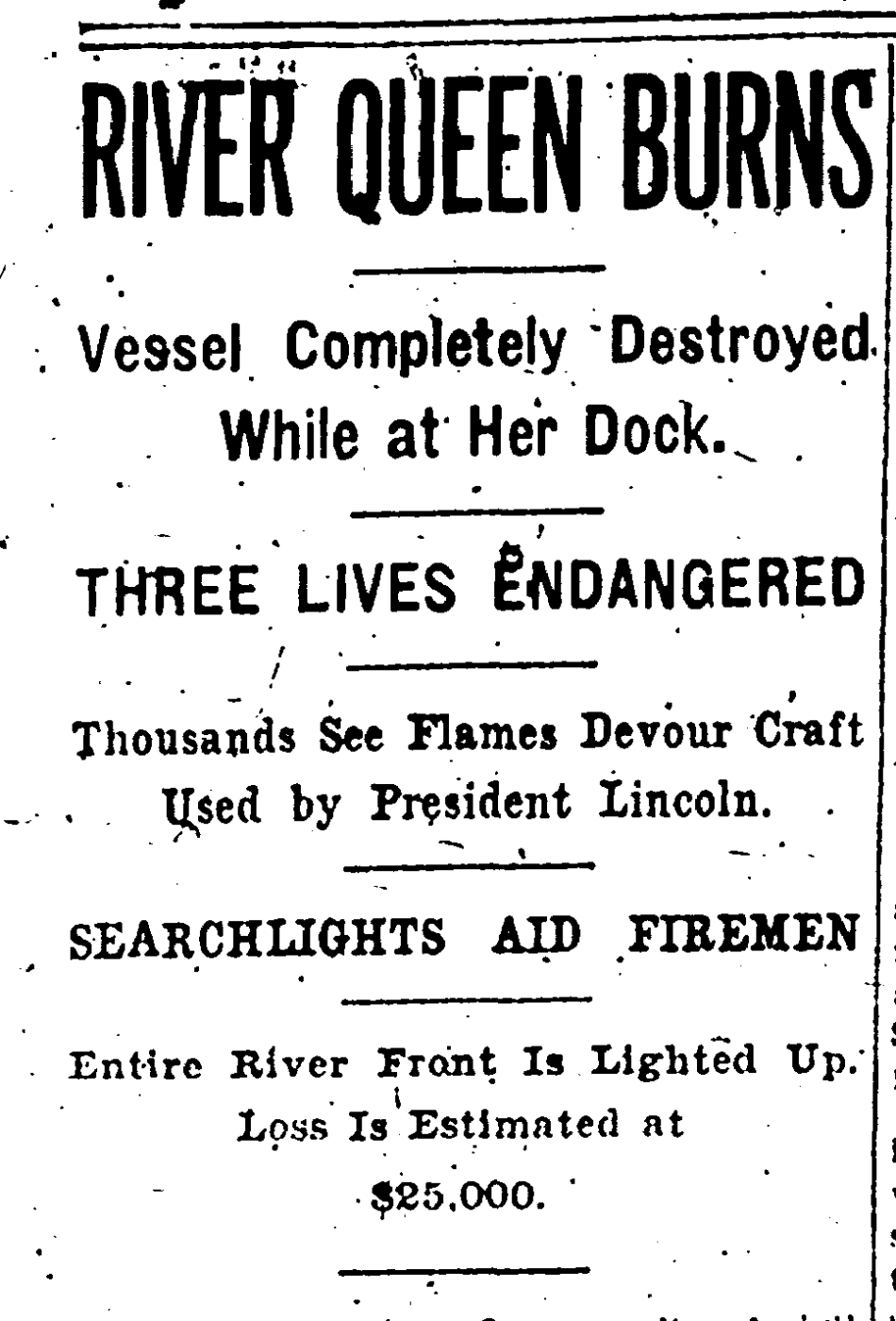

From 1898 to 1911, a 181-foot-long sidewheel steamboat called the River Queen docked at a wharf at the foot of Prince Street in Alexandria. Built in 1864, it had first gained fame as the site of an unsuccessful peace conference in early 1865 between President Abraham Lincoln and representatives of the Confederacy.[1] By the end of the century, owners remodeled the steamer for day-long excursions that catered to African American pleasure seekers. In Alexandria and elsewhere along the Potomac, African Americans boarded the ship to travel up and down the river and visit Black-only recreational resorts.

The River Queen and Black-only resorts were part of the evolution of the river from a place of work to a place of leisure. Despite the entrenchment of Jim Crow segregation, African Americans wanted to be part of the Potomac’s new recreational role in the region.[2] In recognition of African American purchasing power, a white-owned company purchased the River Queen in 1898 for summer excursions. Churches, fraternal organizations, labor unions, and social clubs could book the boat for a trip. One of its most popular destinations was Notley Hall. A struggling white resort near present-day National Harbor on the Maryland shore, Notley Hall began to cater exclusively to African American excursion parties in 1894 and featured a dancing pavilion, shooting gallery, swings, bowling alley, merry-go-round, horse riding track, and electric lights.[3]

The River Queen sailed from Washington, D.C. to Notley Hall, occasionally docking here at the foot of Prince Street to take on board charter groups arranged by African American organizations, like the Fern Street Social Club on Princess Street.[4]

The Colored American, a Black-owned newspaper, wrote in 1902 that the River Queen was patronized by “ladies looking as charming as June roses, in natty costumes, and the masculine contingent was on hand to see that they lacked nothing to round out the pleasure of the hour.” Two years later, the newspaper was less flattering. “These excursions are operated by white men, for the purpose of making money off of the very colored people whom they refuse to rent houses to except in alleys, whom they refuse to employ except in the most menial way, and whom they Jim Crow in every possible way.”[5]

In May 1911, Washington-based Black entrepreneur, Lewis Jefferson, purchased the River Queen as part of his excursion empire. A millionaire by the age of thirty, Jefferson had a minority stake in Notley Hall by 1901 and managed the resort. He also owned another excursion vessel, Jane Moseley, which he bought in 1904. With the purchase of the River Queen, Jefferson began running daily trips on the Potomac under its new captain, Alexandrian George Baggett, who was also African American.[6]

Tragedy unfortunately struck the River Queen soon after Jefferson purchased it. Late on the evening of July 8, 1911, the steamer caught fire while tied to its dock in Washington, D.C. and burned to a blackened hulk.[7] Afterward, its machinery was removed, and the remains were dismantled and carried to a junkyard.[8]

![[Two young African American women, probably somewhere in Virginia]](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_thumbnail/public/2022-07/excursion.png?h=066cba88&itok=X9XX4f89)

![[Two young African American women, probably somewhere in Virginia]](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_item/public/2022-07/excursion.png?itok=EgJi1pJa)

Stop 4: Footnotes

[1] “American Lloyd’s Register of American and Foreign Shipping 1865,” Digital Library: Ship Registers, accessed December 15, 2021; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 822-824.

[2] Andrew W. Karhl, “‘The Slightest Semblance of Unruliness:’ Steamboat Excursions, Pleasure Resorts, and the Emergence of Segregation Culture on the Potomac River,” Journal of American History 94, no. 4 (March 2008): 1114.

[3] Karhl, “‘The Slightest Semblance of Unruliness’,” 1116-1117; Fletcher, 62-62; “The Marshall Hall Sale,” Alexandria Gazette March 29, 1898; “Mount Vernon Steamers,” Alexandria Gazette April 2, 1898; “Advertisement,” Washington Bee July 1, 1899; Patsy Mose Fletcher, African American Leisure Destinations Around Washington, D.C. (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2015), 55.

[4] “Local Matters,” Alexandria Gazette August 15, 1898; “New Wharf,” Alexandria Gazette April 30, 1902; “Search for the Firebugs,” Washington Times June 29, 1898.

[5] “Battle on River Boat,” The Colored American June 18, 1904; “The Amphions Score Again,” The Colored American August 30, 1902.

[6] Kahrl, “‘The Slightest Semblance of Unruliness’,” 1117-1118; “River Queen” and “The Steamer ‘River Queen,” Washington Bee May 13, 1911; “River Queen,” Washington Bee June 17, 1911; “Advertisement,” The Washington Herald June 5, 1911.

[7] “Burning of the Steamer River Queen” and “Burning of the River Queen,” Alexandria Gazette July 10, 1911; “River Queen Destroyed,” Baltimore American July 10, 1911.

[8] “Passing of the River Queen,” The Washington Times January 25, 1912; Andrew W. Kahrl, The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 47.

Stop 5: Shipbuilding in Early Alexandria

Point Lumley Park

Trail Sign: Shipbuilding at Point Lumley

18th Century

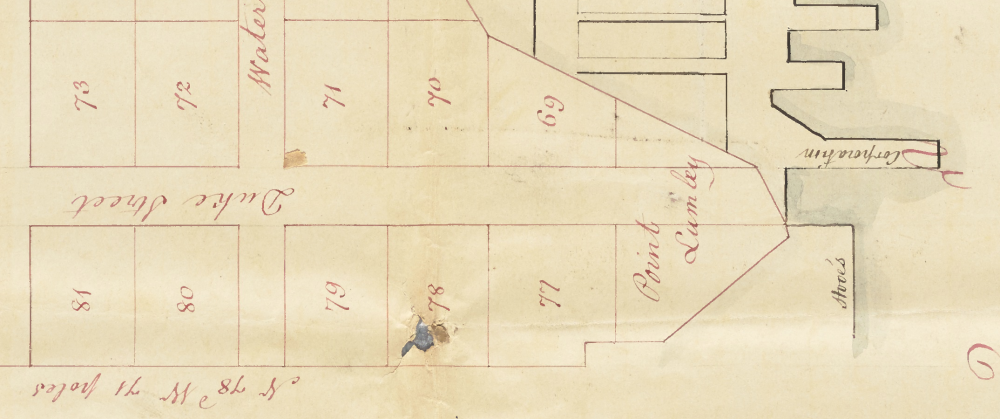

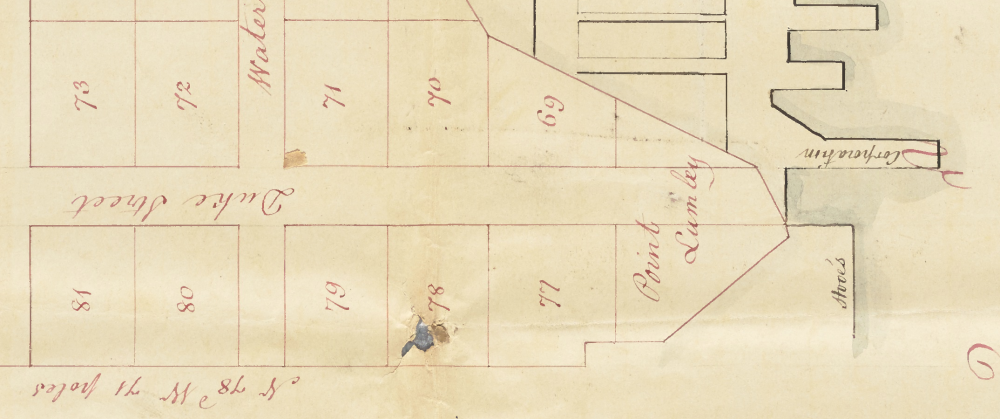

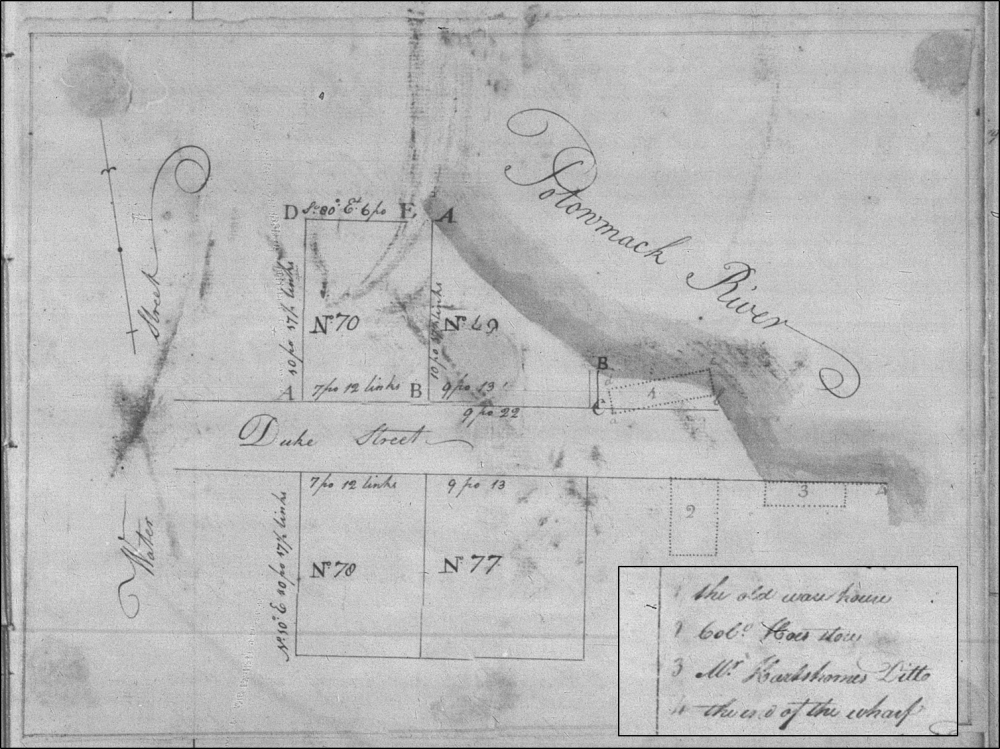

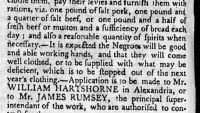

An extensive amount of man-made land hides the original topographical feature that characterized the southernmost tip of Alexandria’s crescent-shaped bay, an area known from at least the 1760s as Point Lumley. As it does today, the town owned the tip of the point. The Town Trustees (the predecessors to today’s City Council) funded the establishment of a road that cut through the steep bank, extending Duke Street to the river’s edge. Here, the Trustees leased parts of Point Lumley for an early shipbuilding business.[1]

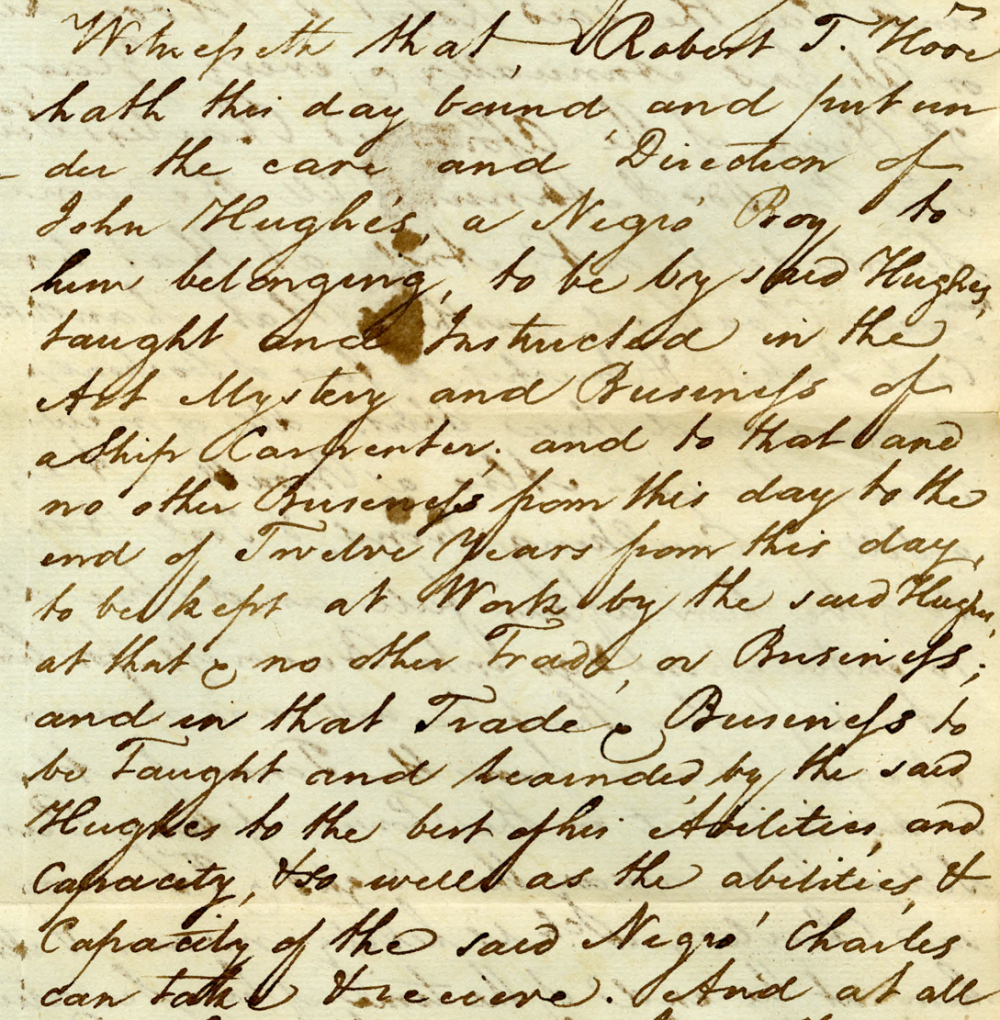

We know something of the shipbuilding trade in Alexandria during this general period from a record that documents an agreement between two white men about the apprenticeship of an enslaved boy named Charles. In 1800, Robert Townsend Hooe signed an Indenture of Apprenticeship with John Hughes, a ship builder and sea captain in Alexandria. Hooe, a merchant, owned a warehouse on Point Lumley. The terms of the agreement included some remarkable details: “a Negro Boy belonging to Hooe be taught and instructed by Hughes in the Art Mystery and Business of a Ship Carpenter and no other Business for a period of 12 years.” Hughes agreed to apprentice Charles to “the best of [Hughes'] abilities,” after which period he would be emancipated and able to enter the business a free man. The agreement is explicit about the proper conditions and treatment that Charles should receive. He “shall be cloathed fed and lodged in that comfortable manner that is humane and suitable for such an apprentice that he shall be found a physician and phusic during the whole time of his apprenticeship when ever it may be necessary and all these things done at the expense of the aforesaid John Hughes.” Upon the end of the term, Charles would be freed with a full suit of clothes and the tools necessary to start his own business, including “a broad ax, adds [adze], a sett of caulking irons and tool box.”[2]

Bits and pieces of information survive to tell us about Alexandria’s first shipbuilding operation in the decades before Charles’ apprenticeship. An English visitor to Alexandria named Reverend Andrew Burnaby observed in 1759, “The town is built upon an arc of this bay; at one extremity of which is a wharf; at the other a dock for building ships; with water sufficiently deep to launch a vessel of any rate or magnitude.” Burnaby very likely saw and described Thomas Fleming’s shipyard located here on Point Lumley. Shipping records account for 18 ships constructed in Alexandria in the years between 1752 and 1776, and Fleming likely built or supervised the construction of many of these vessels until he retired from the business around 1780.[3]

Between 2015 and 2018, archaeologists uncovered four ship hull remnants on either side of Point Lumley, reused at the end of their lives as merchant vessels to construct new land. Research has yet to uncover the names of these ships or their places of origin, but, regardless of where they were built, after they were buried, they became a physical piece of Alexandria.[4]

While the construction and launching of ships required only a few impermanent structures (a saw pit, outbuildings, and a launch ramp or wharf), the skills involved in building ships required training and experience. Crafts people who typically worked on the waterfront included shipwrights, joiners, caulkers, trunnelmakers, pumpmakers, riggers, blockmakers, masons, tinners, glaziers, mastmakers, sailmakers, ropemakers, painters, coopers, tanners, carvers, and boatwrights.[5] Whom did Fleming hire or enslave to build ships in Alexandria? Little is known. No probate inventory of his estate survives; these documents often list the property of an owner, including enslaved people. There is also no tax or census data from this early period to inform us of the demographics of Fleming’s household.

Though Charles’ Indenture of Apprenticeship agreement dates about 20 years after Fleming left the ship building business, the document provides context for the complexity of race and labor relationships in a slave society whose economy was intertwined with the maritime trade. As research continues, we seek to learn more about Alexandria’s early ship building businesses and the people who contributed to its success in the years before and after the American Revolutionary War.

Stop 5: Footnotes

[1] Ted Pulliam, “Point Lumley, Its Location, Appearance, and Structures 1749-1809,” (unpublished manuscript, Alexandria Archaeology, October 2006); Julia Claypool and Edna Johnston, “Robinson Terminal South Property History,” November 12, 2014, accessed December 17, 2021.

[2] Charles (M): Indenture of Apprenticeship, 1800, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, accessed December 20, 2021.

[3] Donald G. Shomette, “Maritime Alexandria: An Evaluation of Submerged Cultural Resource Potentials at Alexandria, Virginia” (Alexandria: Alexandria Archaeology, January 1985), 33-36, accessed December 17, 2021.

[4] “Archaeology on the Waterfront,” City of Alexandria, Virginia, accessed December 27, 2021; Daniel Baicy, David Carroll, and Elizabeth Waters Johnson, “Archeological Evaluation and Mitigation of Hotel Indigo (220 South Union Street),” vol. 1 (Gainesville, VA: Thunderbird Archeology, 2020), accessed December 27, 2021.

[5] Shomette, 36.

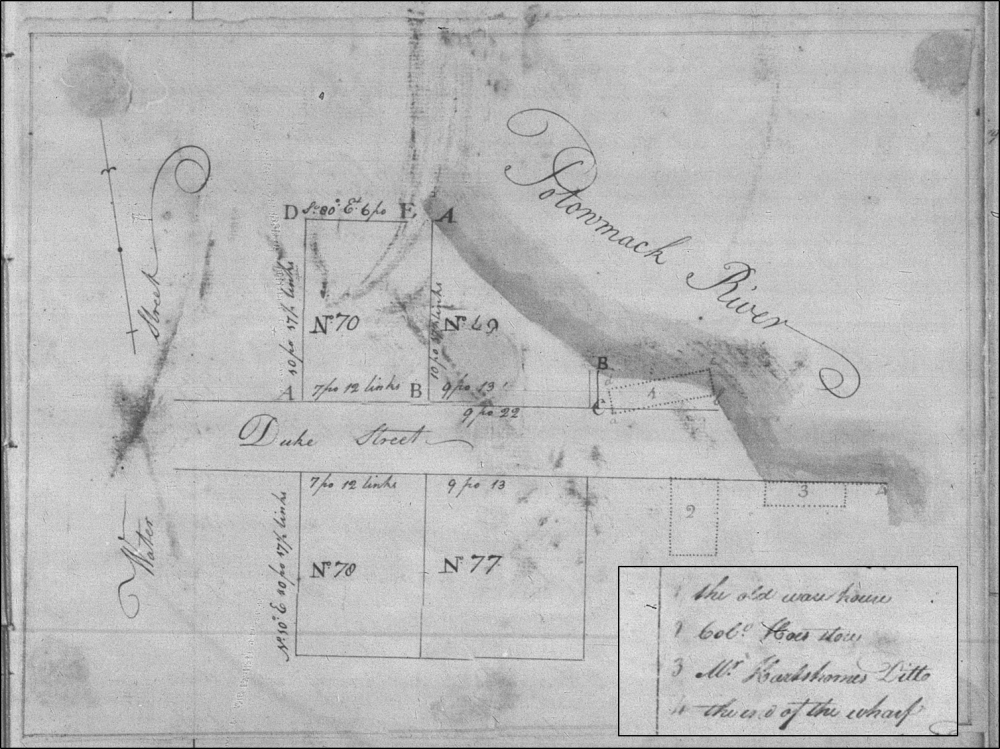

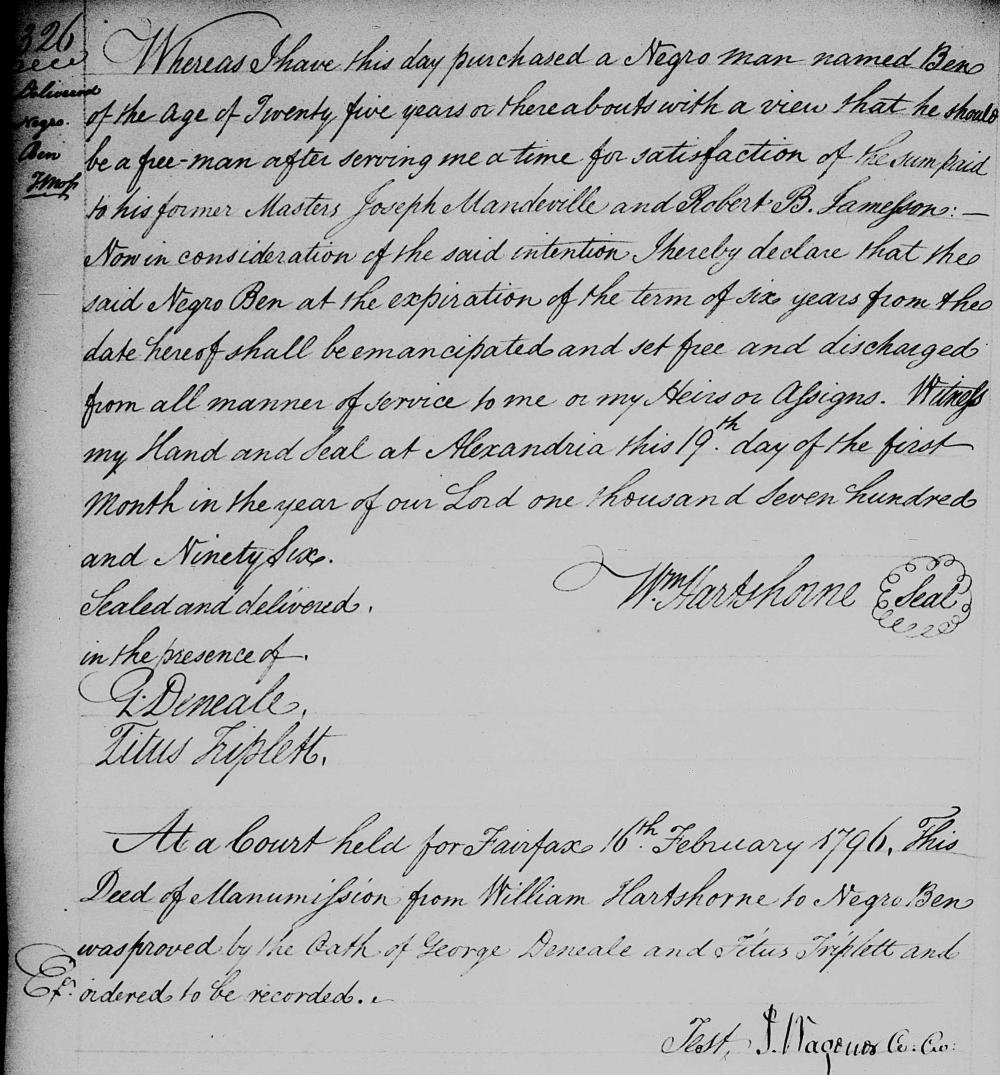

Stop 6: Quakerism and the Anti-Slavery Movement

Intersection of Duke Street and The Strand

18th Century

While conducting excavations along the foot of Duke Street in 2018, archaeologists uncovered the partial remains of a late 18th century store and warehouse located here, just east of The Strand. This place offers an opportunity to tell the story of Quakers, also known as the Society of Friends, and the anti-slavery movement. In the decades before the American Revolutionary War, the religious teachings of Quakerism included a commitment to pacifism, simplicity, and equality in the eyes of God, teachings that ultimately led to a condemnation of slavery.[1]

Let’s consider the intersection of slavery and Quakerism through what little we know of the experience of an enslaved Black man named Ben. In 1796, an Alexandria Quaker merchant purchased Ben with the intention of freeing him, likely guided by religious principles. The details of the transaction to free Ben, however, show that he would have to wait another six years for manumission (or freedom). The deed recording the transaction states:

Whereas I have this day purchased a Negro man named Ben of the age of Twenty five years or thereabouts with a view that he should be a free-man after serving me a time for satisfaction of the sum paid to his former Masters Joseph Manderville and Robert B. Jamesson. Now in consideration of the said intention I hereby declare that the said Negro Ben at the expiration of the term of six years from the date hereof shall be emancipated and set free and discharged from all manner of service to me or my Heirs or Assigns.[2]

The Alexandria Quaker in this document was William Hartshorne, owner of the store at this location. The terms of Ben’s manumission expose the deep conflict between Hartshorne’s religious conviction toward freedom and his economic interests as a merchant. Interestingly, Hartshorne did not treat all manumissions equally. A few years later, Hartshorne freed George Triplett, also known as George Kennedy. George Triplett/Kennedy was to be freed immediately upon purchase. [3]

Born a Quaker in New Jersey in 1742, Hartshorne established himself in Alexandria in the 1770s after brief stints in Philadelphia and Antiqua. He built the store at this location in 1786 and advertised a variety of everyday consumer goods imported from Europe: silk purses; pistols; chocolate; rum; tools; and much more.[4] Hartshorne quickly became a prominent merchant in a town full of prominent merchants, but his religious beliefs and his anti-slavery stance distinguished him from many of his peers. Researchers documented 428 enslavers in the 1810 U.S. Census in Alexandria. Merchants, more than people in any other occupation in Alexandria, owned enslaved people.[5]

Quakers in northern Virginia began to express their anti-slavery stance by expelling those who held enslaved people from local meetings after 1776.[6] However, it took 40 years for the Alexandria Monthly Meeting of Quakers to write out their stance on slavery. In 1816, Hartshorne drafted a report for the meeting that reflected its stance on slavery. It stated that no member shall: own enslaved people; hire slaves for labor from their owners (a practice often referred to as “hiring out”); or conduct business with people who owned or used enslaved labor.[7]

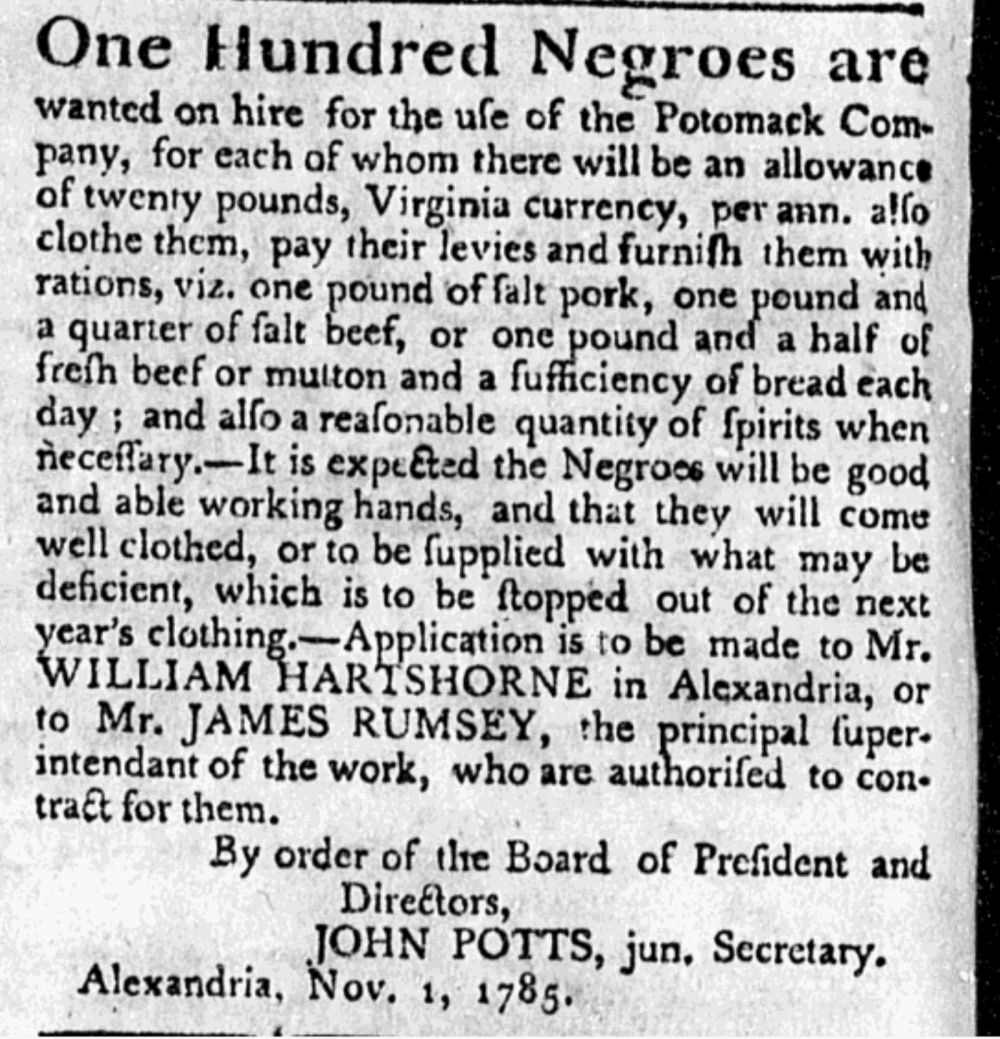

A full separation from enslavement in a southern society like Alexandria proved difficult for Hartshorne and other Quakers, which affected the lives of countless enslaved people like Ben.[8] In a region with an economy and society dependent on the labor of enslaved Africans and African Americans, Hartshorne found fulfilling this Quaker ideal challenging. For example, Hartshorne assumed a leadership role in the Potomac River Company, an endeavor heavily dependent on the use of enslaved labor to construct canals.[9] An advertisement in 1785 announced, “100 negroes are wanted on hire for the use of the Potomac Company for each of whom there will be an allowance of twenty pounds… application to be made to Mr. William Hartshorne in Alexandria or James Ramsay.…”[10] Hartshorne also presided over the Alexandria Maritime Insurance Company, which insured seafaring vessels in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. At least one of the policies, signed by Hartshorne in 1809, insured a voyage from Alexandria to New Orleans carrying 30 enslaved people.[11]

The history of William Hartshorne reveals the extent to which slavery pervaded every aspect of life in Alexandria, even for those who held anti-slavery convictions. It also provides insight into the stories of those enslaved people whose lives intersected with Quakerism.

Stop 6: Footnotes

[1] A. Glenn Crothers, “Quaker Merchants and Slavery in Early National Alexandria, Virginia: The Ordeal of William Hartshorne,” Journal of the Early Republic 25, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 51-55.

[2] Fairfax County Deed Book Y-1-26; Fairfax County Circuit Court’s Historical Records Room, Fairfax, VA.

[3] Tim Denee, “Slave Manumissions in Alexandria Land Records, 1790-1863,” Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery, accessed August 20, 2021.

[4] T. Michael Miller, Artisans and Merchants of Alexandria, Virginia: 1784-1820 (Berwyn Heights, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 1991), 191-193.

[5] Ann Deines, “The Slave Population in 1810 Alexandria, Virginia: A Preservation Plan for Historic Resources” (master’s thesis, George Washington University, 1994), 37-39.

[6] Crothers, 56.

[7] Crothers, 47.

[8] Crothers, 58.

[9] Crothers, 71; Barbara Boyle Torrey and Clara Myrick Green, Between Freedom and Equality: The History of an African American Family in Washington, D.C. (Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press, 2021).

[10] Dylan Prichett, “A Look at the African-American Community Through Alexandria’s Eyes: 1780-1810” (unpublished report, Alexandria Archaeology, 1993), 7.

[11] Crothers, 73.

Stop 7: Evidence of Banking Out

North Side of the 100 Block of Duke Street

18th Century

On September 1, 1760, the Trustees of Alexandria decided to rectify what they felt to be a major oversight in the town’s record keeping:

On Examining the Records of the Town we find an Omission in not entering what was agreed on before the day of Sale of any of the said Lotts, that is, that every purchaser of River side Lotts by the terms of the sale was to have the benefit of extending the said Lotts into the River as far as they shall think proper….those who did purchase Lotts on the River side should be entitled to the said privilege that is that each owner of River side Lotts might build on or improve under his Bank as he should think proper Without any Molestation from the Street Called Water Street Intersecting.[1]

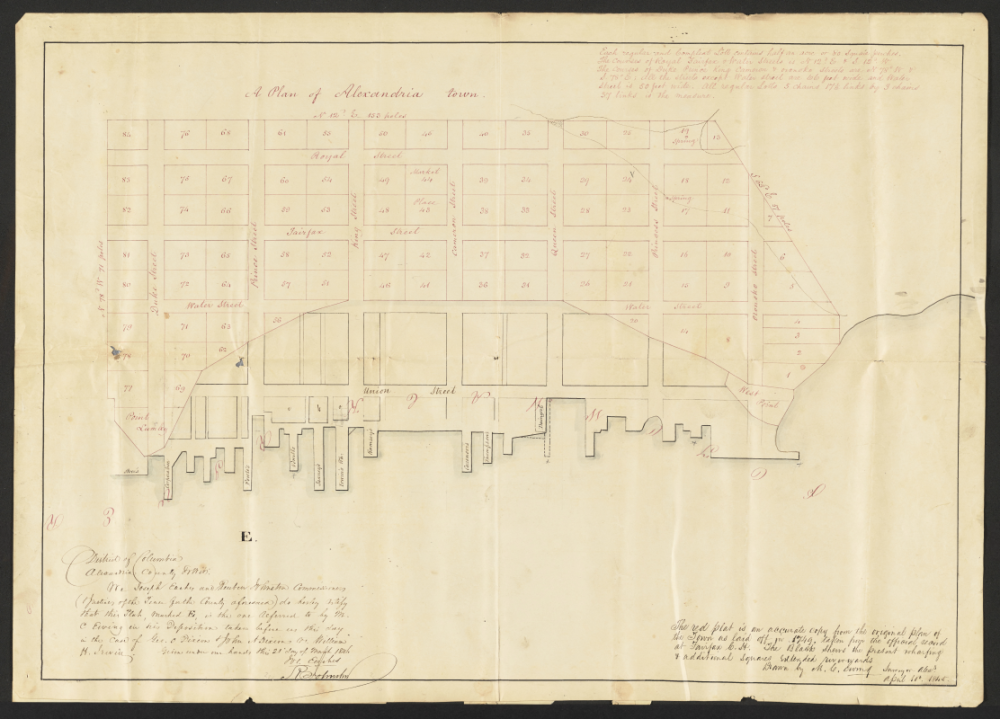

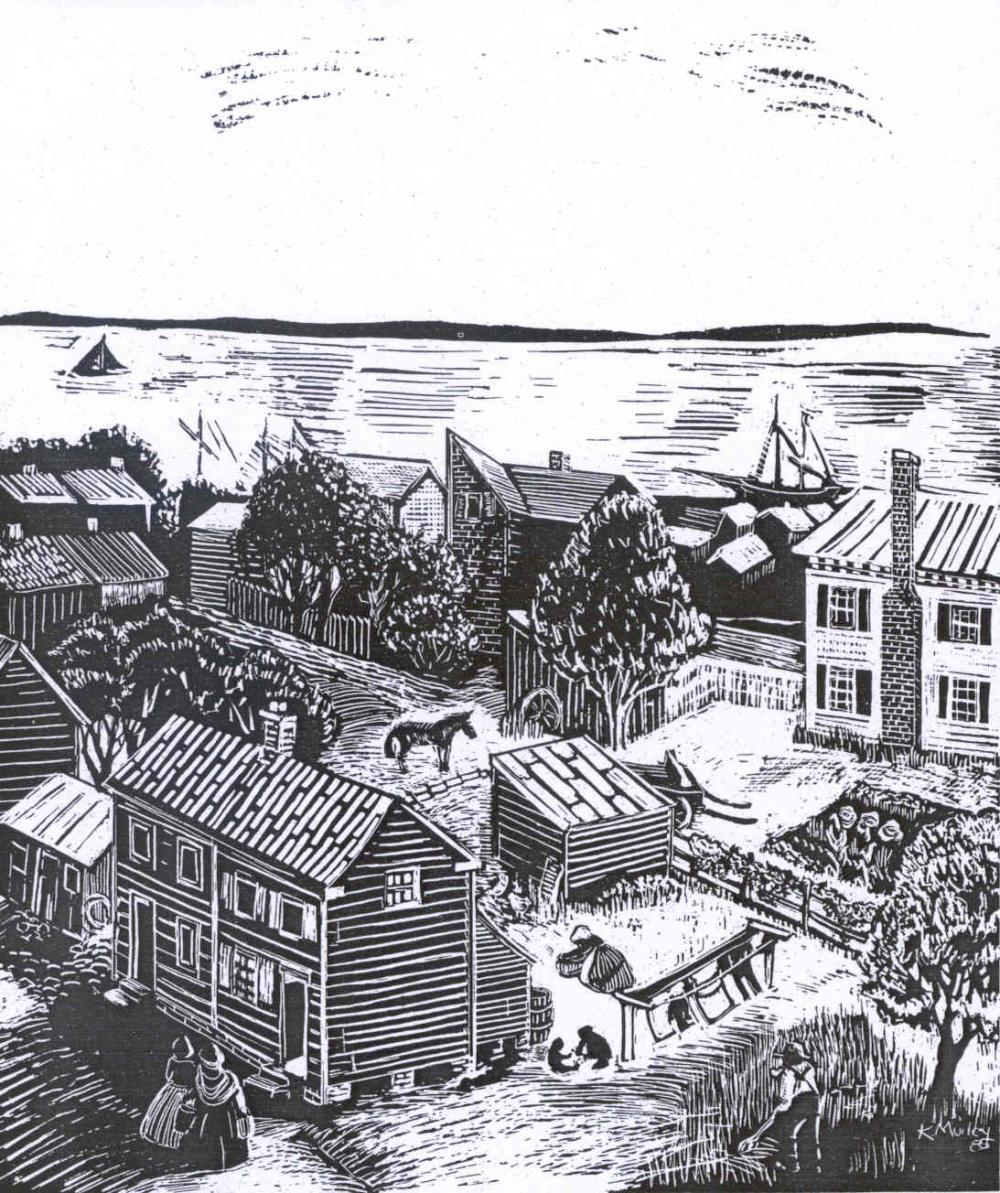

They noted that there was no mention in the official records of an agreement that had been reached prior to the original division and sale of town lots 11 years earlier on July 13-14, 1749 and stated that those who purchased waterfront lots could expand their properties eastward by filling in the Potomac River. Building on and expanding the waterfront was on the minds of early Alexandrians from the day the town was founded, and by the early 1760s, this process was common enough that the Trustees felt the need to codify the right of owners of waterfront property to “bank out.” Over the next half-century, Alexandrians added at least 13 city blocks—about one million square feet—to the city as they dug into the steep rise just above the Potomac’s bank and used that dirt to fill in the river.[2]

Located on this parcel between 111 and 115 Duke Street is one of the last remnants of the original embankment down to the Potomac River in Old Town Alexandria. Throughout the last quarter of the 18th century, Alexandrians “banked out” all along the waterfront, cutting into this embankment and depositing the soil at the edge of the river. A young George Washington, then an assistant to Fairfax County Surveyor Daniel Jennings, noted on this 1748 plat that the “shoals or flats” in front of what would become Alexandria are only “about 7 feet at high water.” He also stated “that in the Bank fine cellars may be cut from thence wharfs may be extended on the flats with any quality and warehouses built thereon as in Philadelphia &c.”[3]

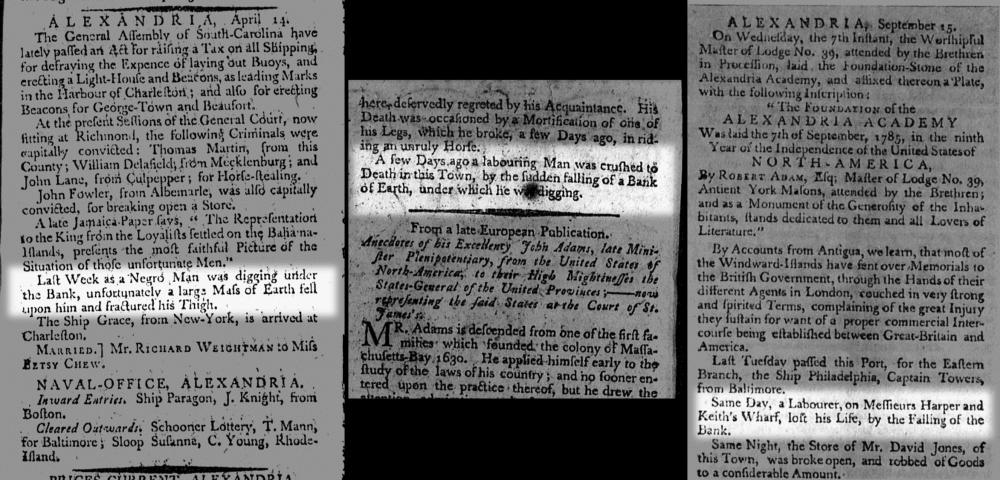

References to “made ground” or parcels located “under the bank” can be found in early Alexandria newspapers.[4] We do not know very much about the people who labored to cut down this bank and fill in the river except through the newspapers. One notice, on September 7 of the same year, simply stated that “...a Labourer, on Messieurs Harper and Keith’s Wharf, lost his Life, by the falling of the Bank.” At least some of the workers were African American, and we know that the work was dangerous. On April 14, 1785, the Alexandria Gazette reported that “Last week as a Negro Man was digging under the Bank, unfortunately a large Mass of Earth fell upon him and fractured his Thigh.” These brief accounts shed light on a largely undocumented, yet massive and costly, effort to fill in Alexandria’s mudflats with earth.[5]

Stop 7: Footnotes

[1] Alexandria, Virginia Town Lots 1749-1801. Together with the Proceedings of the Board of Trustees 1749-1780, ed. Constance K. Ring and Wesley E. Pippenger (Berwyn Heights, MD: Heritage Books, Inc. 2019), 139.

[2] This figure is arrived at by comparing the shorelines depicted on the original 1749 town plan with the 1798 George Gilpin map of the City.

[3] George Washington “Plat of the land where on stands the town of Alexandria” (n.p., 1748), accessed December 18, 2021.

[4] For example, “Robert Adam,” Virginia Journal and Advertiser March 3, 1785; “Alexandria,” Virginia Journal and Advertiser April 14, 1785; “Advertisement,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser October 25, 1802.

[5] “Alexandria” Virginia Journal and Advertiser September 15, 1785, 3; “Alexandria”, Virginia Journal and Alexandria Advertiser April 14, 1785, 3; “Alexandria” Virginia Journal and Advertiser August 25, 1785, 2.

Stop 8: Everyday Life of Free African Americans

Robinson Landing, Pioneer Mill Way

19th Century

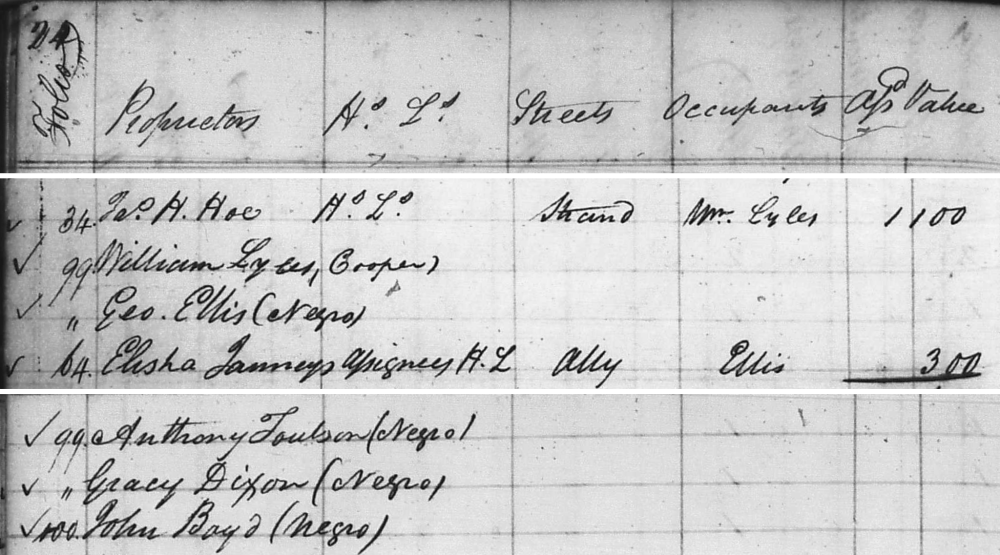

In 1810, over 50 years before the ratification of the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery, four free Black families lived to your left as you walk up Pioneer Mill Way toward the river. Historically, there was a 15-foot-wide alley off The Strand near modern day Pioneer Mill Way. These families rented one-story, wood-framed houses from white landlords along the alley.

Based on census and city tax records, we know the names of the people living here. George Ellis was a laborer and lived with his wife and one child. John Boyd, a seaman, lived next door with his wife and seven others, who might or might not have been related to them. Gracy Dixon, who may have been a washerwoman, lived alone, one of the few single free women we see in this area. Finally, Anthony Tolson, another laborer, resided with his wife. They had no children.[1]

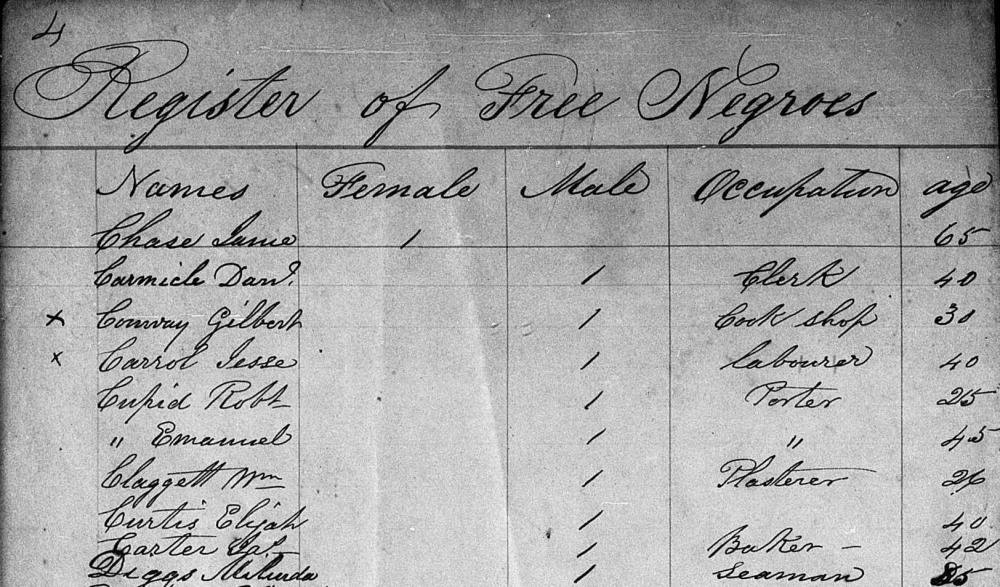

Few records exist that document Alexandria's free African American residents in the Early Republic period (ca. 1780-1830); however, we do know, from the limited sources available, that they found ways to have independent lives.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the state legislature recognized persons of African ancestry as “free” through birth or manumission. To be free, a person had to be: (1) a child born of free Black parents, (2) a child of mixed Black and white ancestry born of a free Black mother, (3) a child of mixed Black and white ancestry born of a white female servant or a free white woman, (4) a child of free Black and Native American mixed parentage, or (5) an enslaved person who had been manumitted (legally freed). An enslaved person could be manumitted by one of three methods: (1) a will, (2) a deed, or (3) an act of a legislature.[2]

Prior to the Civil War, a free Black person, however, was not entirely free, not in the sense that a white person was free. According to historian, Belinda Blomberg, free Blacks in Alexandria and elsewhere “occupied a marginal position between two societies, slave and white.” Unlike enslaved people, they could receive an education, own homes, establish churches, and pursue a limited number of occupations; however, Blomberg also points out that their “personal safety eluded them, and basic human dignity was begrudged them.”[3]

Because Alexandria was urban, there were more job opportunities than in the countryside, particularly in the town’s expanding economy after the Revolutionary War. Laborers like George Ellis and Anthony Tolson would have possibly worked on the docks near their homes, loading and unloading ships and running errands for captains and dock owners. A white family could have employed a washerwoman like Gracy Dixon to do specialty work, like caring for linen, satin, and silk garments. For a seaman like John Boyd, there would have been opportunities on the numerous sailing ships that docked in Alexandria, although a Black seaman’s position aboard ship was frequently limited to cook or steward. A family man like Boyd probably preferred work in the coastal, rather than international, trade.[4] As renters of these wood-framed houses located in one of Alexandria’s alleys, they were likely among the poorest of its residents. Few free African Americans had the means or opportunity to own a home in the Early Republican period, and their economic and legal status was far from certain.[5] The tax listings in 1820 do not record any of the four families still living in the alley or in the City. Unfortunately, it was difficult even for free Blacks to put down roots in Alexandria.[6]

The social and economic realities faced by free African Americans became more perilous after Nat Turner’s rebellion in southwestern Virginia in 1831. The rebellion greatly increased whites’ anxiety about free Black men and women over whom they had less control than enslaved. In Alexandria, free Blacks themselves feared white reactions to their businesses, lives, community, and freedom. Shortly after the rebellion, 46 free Black Alexandrians wrote a letter declaring their “abhorrence of the recent outrage” and pledging they would “promptly give public information of any plot, design or conspiracy” that might “disturb the peace and jeopardize the safety of the community.[7]

In 1847, another event created additional anxiety among Alexandria’s free Black residents. The city left the District of Columbia and became part of Virginia again. Virginia maintained many more restrictive regulations and practices towards free African Americans. In response, many free Black residents left Alexandria as soon as they could; others remained.[8]

Stop 8: Footnotes

[1] “Alexandria City Census, 1799, 1800, 1808, 1810, 1816, 1830,” microfilm, Special Collections, Kate Waller Barrett Branch Library, Alexandria, VA; Anna M. Lynch, comp., A Compendium of Early African Americans in Alexandria, Virginia, vol.1 (Alexandria: Alexandria Archaeology Publications, 1993), 20.

[2] Belinda Blomberg, “Free Back Adaptive Responses to the Antebellum Urban Environment: Neighborhood Formation and Socioeconomic Stratification in Alexandria, Virginia, 1790-1850” (Ph.D. Diss., American University, 2016), 26, 30-31.

[3] Blomberg, 25, 49.

[4] Blomberg, 27-28, 32, 47-48, 218-219; Bolster, 158-159, 162-165, 167-168.

[5] Blomberg, 298.

[6] T. Michael Miller, Portrait of a Town, Alexandria, District of Columbia, 1820-1830 (Berwyn Heights, MD: Heritage Books, 1995), 503; Garrett Fesler, “Nat Turner and the 46 Petitioners,” Alexandria Archaeology, April 29, 2021, Zoom talk, documentary video, 52:43, accessed December 26, 2021; Blomberg, 67-68.

[7] Blomberg, 41-42, 66-67; “Communicated,” Alexandria Gazette October 4, 1831; Fesler, “Nat Turner and the 46 Petitioners.”

[8] Blomberg, 67-68, 83. Blomberg has Alexandria retroceding in 1846; however, that was the year when the federal government enacted a bill permitting such an act. Retrocession was not finalized until the Virginia General Assembly accepted the readmission of Alexandria, which it did in 1847. “Virginia Legislature,” Alexandria Gazette March 16, 1847.

Stop 9: African American Workers on the Railroad during the Civil War

Sign at Wilkes Street Tunnel, east end

19th Century

The Wilkes Street Tunnel was part of the eastern division of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad founded in 1848 to promote trade with western Virginia. Located nearby, the Smith and Perkins Foundry also manufactured locomotives for the Orange & Alexandria and other railroads.

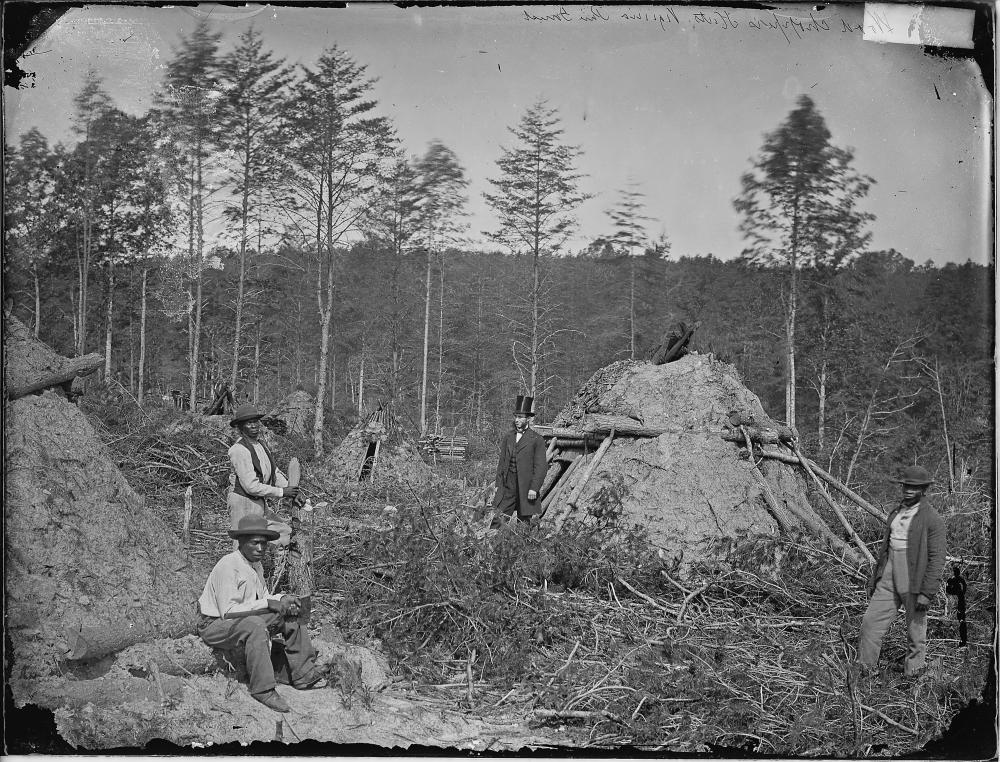

At the onset of the Civil War, the Orange & Alexandria line was one of many Alexandria railroads taken over by Union forces. Many free and formerly enslaved African Americans found employment as laborers for the U.S. military on the City’s several railroads, which transported supplies and soldiers to the warfront. African American men found additional jobs in the construction and maintenance of forts and military roads surrounding Washington, D.C., the logistics and distribution of supplies through the Army Quartermaster’s offices, and construction and operations with the U.S. Military Railroad (U.S.M.R.R.). In command of the U.S.M.R.R was General Herman Haupt, who wrote in his memoirs of the contribution and impact of African American men in the Construction Corps:

With the exception of the superior officers and the foremen, the Construction Corps consisted almost entirely of so-called “contrabands.” Thousands of these refugees had flocked into Washington, and from them were selected several hundred healthy, able-bodied men familiar with the use of the ax. These Africans worked with enthusiasm, and each gang with a laudable emulation to excel others in the progress made in a given time…. If there ever should be recognition of their great services, the faithful contrabands will be justly entitled to their share; no other class of men would have exhibited so much patience and endurance under days and nights of continued and sleepless labor.[1]

No language is too strong to commend the efficiency of this Corps, or the importance of the service it rendered.…[2]

Some of the best documentation of these Civil War-era projects and infrastructure in Alexandria, including the Union Army’s African American workforce, comes from soldier and photographer Andrew J. Russell. Russell enlisted in the Union Army in 1862 and served with the 141st New York Volunteers until he was reassigned to the U.S.M.R.R. Construction Corps under General Haupt in March 1863. Haupt tasked Russell with photographing some of the major projects under his command for inclusion in official reports, and it is for this reason that Russell’s photographs are notable. Unlike those of his contemporaries, such as Mathew Brady or Alexander Gardner, most of Russell’s images do not portray military leaders and battlefields; instead, they recorded the daily logistical challenges faced by the U.S. military and efforts to overcome them. These photographs include transportation infrastructure like port facilities and railyards, bridge building and repair activities, construction and repair work along the railroad, and experimental engineering projects designed to improve wartime logistics.[3]

While not their intended purpose, Russell’s photographs give glimpses of African American men working to support the war effort, and many of them were taken in and around Alexandria.

![[Railroad construction workers]](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_item/public/2022-07/tunnel.png?itok=vXL2zGMv)

![[Military railroad operations in northern Virginia: men using levers for loosening rails]](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_thumbnail/public/2022-07/militaryrailroad2.png?h=956097f9&itok=2IcIsbHT)

![[Military railroad operations in northern Virginia: men standing on railroad track]](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_thumbnail/public/2022-07/militaryrailroad.png?h=e29f1425&itok=de5SLVtI)

![[Railroad construction workers]](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_item/public/2022-07/tunnel.png?itok=vXL2zGMv)

![[Military railroad operations in northern Virginia: men using levers for loosening rails]](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_item/public/2022-07/militaryrailroad2.png?itok=AeamD8DH)

![[Military railroad operations in northern Virginia: men standing on railroad track]](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_item/public/2022-07/militaryrailroad.png?itok=M-RA8ljm)

Stop 9: Footnotes

[1] Herman Haupt, Reminiscences of General Herman Haupt (Milwaukee: Wright & Joys, 1901), 319.

[2] Haupt, 64.

[3] “Preface”, Joe Buberger and Matthew Isenberg, Russell’s Civil War Photographs: 116 Historic Prints by Andrew J. Russell, Dover Publications, 1982; “‘Richmond Again Taken’. Reappraising the Brady Legend through Photographs by Andrew J. Russell”, Susan E. Williams, The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 110, No. 4, pp. 437-460, 2002.

Stop 10: Hayti, An African American Neighborhood

Intersection of Wilkes and S. Royal Streets

Trail Sign: Hayti

19th Century

In 1804, Francois-Dominique Toussaint L’Ouverture, a formerly enslaved Haitian Black military leader, led the only successful uprising of enslaved people in the Western Hemisphere. As a result of the rebellion, the Caribbean island of Haiti declared independence from European powers. This international event reverberated throughout the United States all the way to Alexandria. Around this time, free African American residents in the city formed a neighborhood that came to be called Hayti (pronounced Hay-tie), generally located from South Fairfax to South Pitt Streets and Prince to Gibbon Streets. The first documented use of the neighborhood name came in the Alexandria Gazette in 1860.[1] A few years later, the Union Army established a hospital in Alexandria for wounded soldiers called L'Ouverture (on the block bounded by Prince, Duke, Payne, and West Streets) in solidarity with the cause of freedom.[2] The name Hayti is also found associated with other historic African American communities in North Carolina and Missouri; however, Alexandria’s neighborhood appears to be the oldest.[3] Associating these neighborhoods with revolution, one can find African American expressions of agency, resistance, and ownership at the heart of these communities.

By 1860, Alexandria had the third largest population of free Blacks among Virginia’s cities.[4] Opportunity for jobs, relative safety and stability, and the potential to gain freedom contributed to the rapid growth of the free Black population beginning around 1820. The influence of local Quakers, guided by anti-slavery beliefs, may have also supported the development of Hayti and other African American neighborhoods through the practice of renting and, in some cases, selling houses to free African Americans.[5] Quakers William Hartshorne, Mordecai Miller, and his son Robert H. Miller owned property in this neighborhood in the formative years of Hayti’s development. Both Millers constructed houses on their lots and made those dwellings available for free people to rent and eventually own. Historians attribute the role of these Quakers as instrumental in supporting the development of Hayti.[6] The formation of an African American neighborhood in this vicinity has also been tentatively attributed to the establishment of the First Methodist Episcopal Church in 1794, which had a large Black congregation in the early 1800s.[7]

In the 1980s and 1990s, Alexandria Archaeology conducted a series of backyard excavations and archival research into the heart of the Hayti neighborhood on the 400 block of South Royal Street. Documents revealed that between 1815 and 1861, free Black households occupied most of the residences on this block.[8] One of these lots (what became 406 and 408 South Royal Street today) is associated with Hannah Jackson, a free Black laundress who purchased a house from Mordecai Miller in 1820. This purchase made her one of the earliest Black residents and Black women in Alexandria to own property. Illuminating the life of Jackson became the main focal point of the research.[9] Jackson purchased and emancipated family members, including her son and sister, along with her sister’s four children. Jackson’s nephew, whom she helped to raise after her sister passed away, was Moses Hepburn, who became a prominent businessman and local leader.[10]

Archaeological excavations along the east side of 400 South Royal Street included George Lewis Seaton’s house at 404 South Royal Street (archaeological site number 44AX157). Though excavations were limited, archaeologists discovered what they believed to be the earliest material culture related to free Blacks in Alexandria and evidence of the development of the Hayti neighborhood. Seaton, a well-known free Black Alexandrian, became a master carpenter and built residences and prominent civic structures, including two schools for Black children after the Civil War and Odd Fellows Hall, home to fraternal organizations and community events for decades.[11] Seaton began buying and selling property in 1844, and in the 1860 U.S. Census, his real estate holdings totaled $4,000.[12] During Reconstruction, Alexandria residents knew Seaton as a civic leader and in 1869, elected him to the Virginia General Assembly. He was the highest-ranking Black officeholder in the state in the 1870s.[13] Seaton also served on mixed-race juries, including the trial of ex-Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who was charged with treason in 1865.[14]

Stop 10: Footnotes

[1] T. B. McCord, Across the Fence, but a World Apart: The Coleman Site, 1776-1907 (Alexandria: Alexandria Urban Archaeological Program, 1985), 3.

[2] Laura V. Trieschmann, “‘The Faithful Contrabands will be Justly Entitled to their Share,’ A History of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia” (Alexandria, VA: Alexandria September 2015), 183.

[3] Richard Mattson, “The Evolution of Raleigh’s African-American Neighborhoods in the 19th and 20th Centuries” (Raleigh: North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, November 1988), accessed December 18, 2021; “Hayti, Missouri,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, accessed December 18, 2021.

[4] Petersburg and Richmond had the first and second largest populations of free Blacks among Virginia cities in 1860. Susanna Michele Lee, “Free Blacks during the Civil War,” Encyclopedia Virginia: Virginia Humanities, accessed December 18, 2021.

[5] McCord, 25-26.

[6] McCord, 26, 63, 77; See also Crothers, 47-77.

[7] Pamela J. Cressey, “The Alexandria, Virginia City-Site: Archaeology in an Afro-American Neighborhood, 1830-1910” (PhD diss. University of Iowa, 1985), 81-83.

[8] McCord, 23, 38-39.

[9] Sara Revis, “Historical Case Studies of Alexandria’s Archaeological Sites, Hannah Jackson: An African American Woman and Freedom, Archival Data Pertaining to 406-408 South Royal Street” Alexandria Archaeology Publication No. 33 (Alexandria: Alexandria Archaeology, 1991), iii, accessed December 24, 2021.

[10] McCord, 24; Revis, 1.

[11] National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, George L. Seaton House, Alexandria, Virginia, December 2013, accessed December 18, 2021.

[12] Marianne E. Julianne, “George Lewis Seaton,” Dictionary of Virginia Biography, accessed December 27, 2021; 1860 U.S. Census, Alexandria, Virginia, 197, accessed February 7, 2022, ancestry.com.

[13] Peter Bernstein, The Life and Times of George Lewis Seaton (2003; repr., Alexandria: Alexandria Publications, 2001), 27.

[14] Bernstein, 26.

Stops 11-19

- Stop 11: African American Neighborhoods in the Civil War (Windmill Hill Park)

- Stop 12: Zion Baptist Church (714 S. Lee Street)

- Stop 13: “Mr. Philip Alexander’s Quarters” (Intersection of Jefferson and S. Lee Streets)

- Stop 14: USCT at Battery Rodgers (Sign on Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park)

- Stop 15: CCC Camp at Battery Cove (Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park)

- Stop 16: African American Workers at the Virginia Shipbuilding Company (Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park)

- Stop 17: Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge and Freedmen’s Cemetery (Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park)

- Stop 18: Jones Point Ropewalk (Sign on Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park)

- Stop 19: Jones Point and Benjamin Banneker (Jones Point Lighthouse, Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park)

- To Return to Waterfront Park

- Conclusion