African American Heritage Trail - South Waterfront Route (stops 11-19)

South Waterfront Route (Stops 11-29)

African American Heritage Trail

South Waterfront Route

Stops 11-19

from Windmill Hill Park to Jones Point Park

Stops 1-10

- Stop 1: Enslaved on the Waterfront (Sign at Foot of King Street)

- Stop 2: The Domestic Slave Trade in Alexandria (Sign at Waterfront Park)

- Stop 3: George Henry, Enslaved Ship Captain (Waterfront Park, Riverside)

- Stop 4: The River Queen (Foot of Prince Street)

- Stop 5: Shipbuilding in Early Alexandria (Point Lumley Park)

- Stop 6: Quakerism and the Anti-Slavery Movement (Intersection of Duke Street and The Strand)

- Stop 7: Evidence of Banking Out (North Side of the 100 Black of Duke Street)

- Stop 8: Everyday Life of Free African Americans (Robinson Landing, Pioneer Mill Way)

- Stop 9: African American Workers on the Railroad during the Civil War (Sign at Wilkes Street Tunnel, east end)

- Stop 10: Hayti, An African American Neighborhood (Intersection of Wilkes and S. Royal Streets)

Stop 11: African American Neighborhoods in the Civil War

Windmill Hill Park

Trail Sign: African American Neighborhoods in the Civil War

19th Century

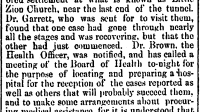

During the Civil War, thousands of formerly enslaved individuals came to Union-controlled Alexandria to seek refuge and freedom. As a result, several new African American neighborhoods developed during and after the Civil War, including four in this vicinity. Three of them, Vinegar Hill, Union Town, and one identified as “near Wilkes Street Tunnel,” appeared in the records kept by Reverend Albert Gladwin, a member of the Baptist Free Missionary Society of New York and Superintendent of Contrabands in Alexandria from 1862 through 1865. His “Book of Records” documented information on those African Americans buried in the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery on South Washington Street. Gladwin, in addition to recording names, dates of death, and ages, also noted the residence or place of death, giving historians a sense of the African American landscape at the time.[1] The fourth community, Zion Bottom, coalesced slightly later with the establishment of a nearby church (see Stop 12) and is the closest neighborhood to this stop.

Community names in greater Alexandria reflected the areas that enslaved people fled from during the Civil War (Petersburg), characteristics of their new settlements (Newtown), or recognition of those who supported the cause of freedom (Grantville). These names, however, and the boundaries of the neighborhoods were also in flux and reflected the flows of African American refugees in and out of the city along with Alexandria’s racial politics.

Union Town (or Uniontown) and Vinegar Hill appear the earliest in Gladwin’s “Book of Records” in 1864. The area near the Wilkes Street Tunnel seems to have also been an African American enclave by 1865. Uniontown is only mentioned three times, and very little is known about the residents, but it may have been associated with the Uniontown School located at the corner of Wolfe and South Union Streets (see Alexandria Map 1865) and established in May 1863. The Uniontown School, under the instruction of a Black teacher named Nancy Williams, reportedly had 80 students in 1865.[2] It is possible that records of free people passing away near the Wilkes Street Tunnel may also have been a general reference to the Black enclave near the Uniontown School or the Uniontown neighborhood. Vinegar Hill, also known as “The Hill” and “Out on the Hill,” appears to have been located further south along the waterfront. Jennie Gray, who passed away in 1866, had come from Vinegar Hill (Gladwin even noted that she lived near Washington, Jefferson, and Columbus Streets). Other records associated Vinegar Hill with Washington and Franklin Streets.[3]

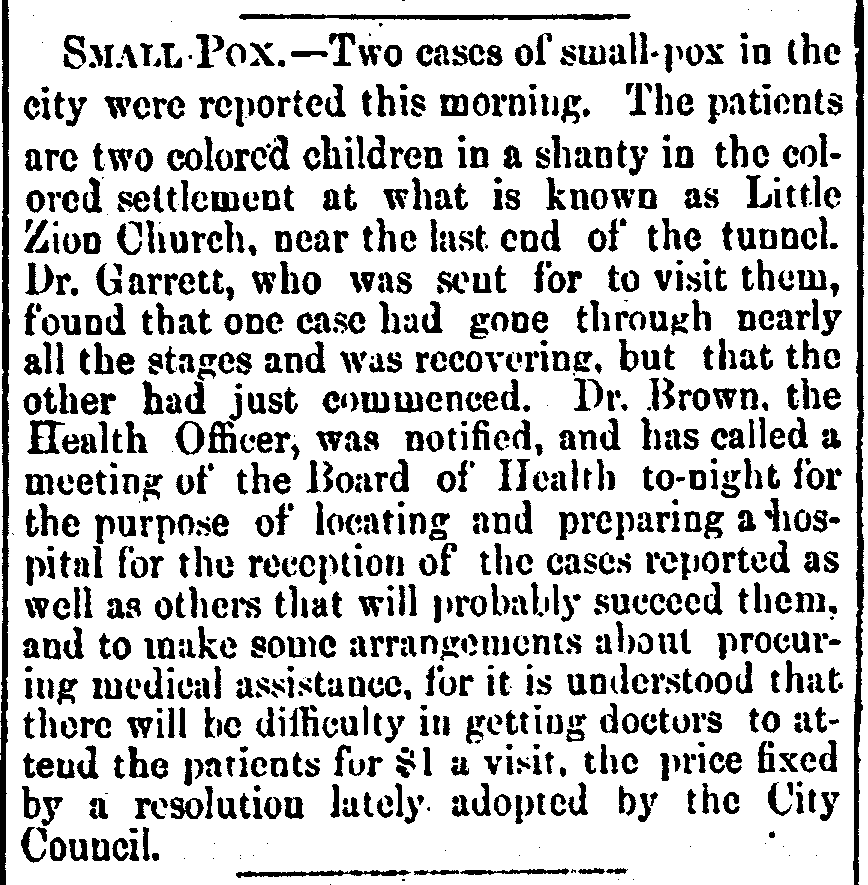

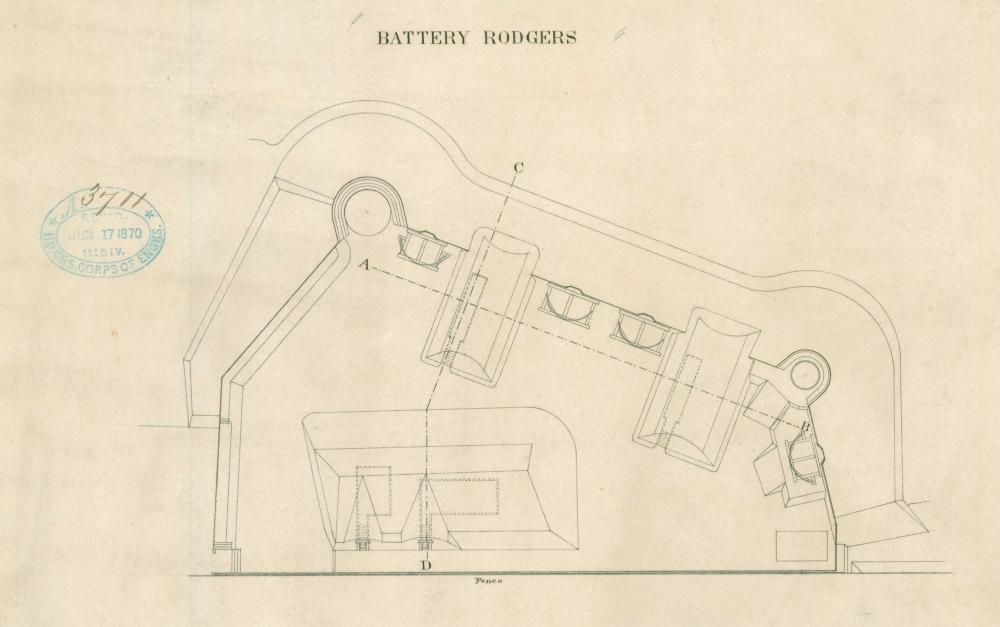

Though the name is not listed in Gladwin’s “Book of Records,” the neighborhood known as Zion Bottom must have had some overlap with the three nearby communities mentioned above. By the early 1870s, residents renamed the low-lying area near the Wilkes Street Tunnel “Zion Bottom,” most likely after Zion Baptist Church, which was initially located here. The neighborhood appeared periodically in the Alexandria Gazette from 1872 through the early twentieth century. For instance, tragedy hit in September 1872, when one of Alexandria’s first smallpox cases, which erupted into an epidemic, occurred in the neighborhood. The medical community initially did not take the situation seriously, and several African American residents became sick and died.[4] Zion Bottom faced another crisis in the summer of 1873 when the Washington City, Virginia Midland and Great Southern Railroad Company demanded that residents accused of squatting on the company’s land had to move so that it could build a distributing depot. Many took their homes—literally piece-by-piece—and rebuilt them on land north of Battery Rodgers. Others settled elsewhere in the city.[5]

Stop 11: Footnotes

[1] Wesley E. Pippenger, Alexandria, Virginia Death Records, 1863-1869 (The Gladwin Record) and 1869-1896 (Westminster, MD: Family Line Publications, 1995).

[2] Special Report of the Commissioner of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia submitted to the Senate June 1868, and to the House, with Additions, June 13, 1870 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), 288.

[3] Wesley E. Pippenger, Alexandria, Virginia Death Records, 1863-1869 (The Gladwin Record) and 1869-1896 (Westminster, MD: Family Line Publications, 1995).

[4] By December 1872, Alexandria had six confirmed cases, three of which were in Zion Bottom and all cases affected African Americans. “Reported Case of Small-Pox,” Alexandria Gazette September 6, 1872; “Alexandria,” Evening Star (Washington, DC) December 16, 1872; “Small Pox,” Alexandria Gazette December 18, 1872.

[5] “Local Brevities,” Alexandria Gazette June 12, 1873; “Local Brevities,” Alexandria Gazette June 14, 1873; “Local Brevities,” Alexandria Gazette June 17, 1873.

Stop 12: Zion Baptist Church

714 S. Lee Street

Trail Sign: Zion Baptist Church

19th Century

A small group of Christian believers established Zion Baptist Church (sometimes called Little Zion) in 1864 on the corner of Wolfe and South Union Streets, northeast of the Wilkes Street Tunnel. At the end of the Civil War, Zion Baptist was one of five African American Baptist churches in Alexandria.[1]

The community was initially under the guidance of Reverend Albert Gladwin, a member of the Baptist Free Missionary Society of New York and the Superintendent of Contrabands in Alexandria from 1862 through 1865.[2] When Gladwin left the city, Zion became an independent congregation led by a small cohort of dedicated African American men and women. Its founding members had settled in Alexandria during the Civil War, and most likely worked for the federal government on the railroad or waterfront. Because of the prominence of the church in this low-lying area, the neighborhood was referred to as Zion Bottom.

In the late 1860s and early 1870s, the church was also used as a meeting place in service to the community. By 1868, the year when African American men first voted in Virginia, Alexandria's First Ward Radical Republicans regularly met at Zion.[3] They also used the church as a meeting place to nominate African American men to political office. In May 1877, local radical Republicans chose George L. Seaton, one of the wealthiest African Americans in Virginia, for City Council along with a handful of other African American men.[4] The church held numerous services, festivals, and other events.[5]

In 1880, the Zion Baptist Church moved to a new location where it still stands today. The reasons for its relocation are unknown; however, the area along Union Street was known to flood.[6] The church’s new location on Lee Street was not only elevated, but also close to the new location of the Zion Bottom neighborhood. The church opened to the public in June 1882, using funds raised by its congregants.[7]

One of the most notable people associated with the church was the renowned Samuel Wilbert Tucker. Born in 1913, Tucker attended segregated schools in Alexandria and Washington, D.C. that left a deep impression on him and would later fuel his fire to fight for Civil Rights. Tucker became "a Civil Rights Lawyer, who played the piano at church and resided with his family at 702 South Lee Street." Tucker's father also "served as superintendent of Sunday School and choir director." Tucker died in 1990 and his legacy continues in Alexandria and across the country.[8]

Today the church serves the community by extending its facility to host various meetings, services and other events. Visit Zion Baptist Church for more information.

Stop 12: Footnotes

[1] United States Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioner of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools of the District of Columbia, submitted to the U.S. Senate June 1868, and to the U.S. House of Representatives, with additions, June 13, 1870 (Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, 1871), 291.

[2] Thomas’s essay says that a “Gladden,” helped to establish the congregation; however, no such person has been found. We believe that Gladden is a typo, and that he must have meant Gladwin. As a member of the Baptist Free Missionary Society, Gladwin actively proselytized among African Americans in the city. Reverend William N. Thomas, “A Study and History of the Zion Baptist Church Alexandria, Virginia” (Alexandria Archaeology, n.d.); History of Schools for the Colored Population (1871; repr., New York: Arno Press, 1969), 287; T. Michael Miller, comp., “A Profile of Zion Church and Environs” (Alexandria: Alexandria Archaeology, May 6, 1997).

[3] “First Ward Radicals,” Alexandria Gazette December 23, 1868; “First Ward Radicals,” Alexandria Gazette June 9, 1869; “Local Matters,” and “Meetings,” The Daily State Journal (Alexandria, VA), August 14, 1871.

[4] “Radical Meetings,” May 19, 1877 from Margarette Cooper (comp.), “Appendix A,” in Bernstein, 69.

[5] Miller, “A Profile of Zion Church and Environs;” “Police Report--Mayor’s Office,” Alexandria Gazette April 4, 1870.

[6] “Alexandria,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 19, 1873.

[7] "Dedication of Zion Church," Alexandria Gazette, October 30, 1882, 4.

[8] Nancy Noyes Silcox, Samuel Wilbert Tucker: The Story of a Civil Rights Trailblazer and the 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In (Fairfax, Virginia, History4All, 2014), 17; Office of Historic Alexandria, Samuel Wilbert Tucker: Unsung Hero of the Civil Rights Movement (Alexandria, VA, nd), accessed January 13, 2023.

Stop 13: “Mr. Philip Alexander’s Quarters”

Intersection of Jefferson and S. Lee Streets

18th Century

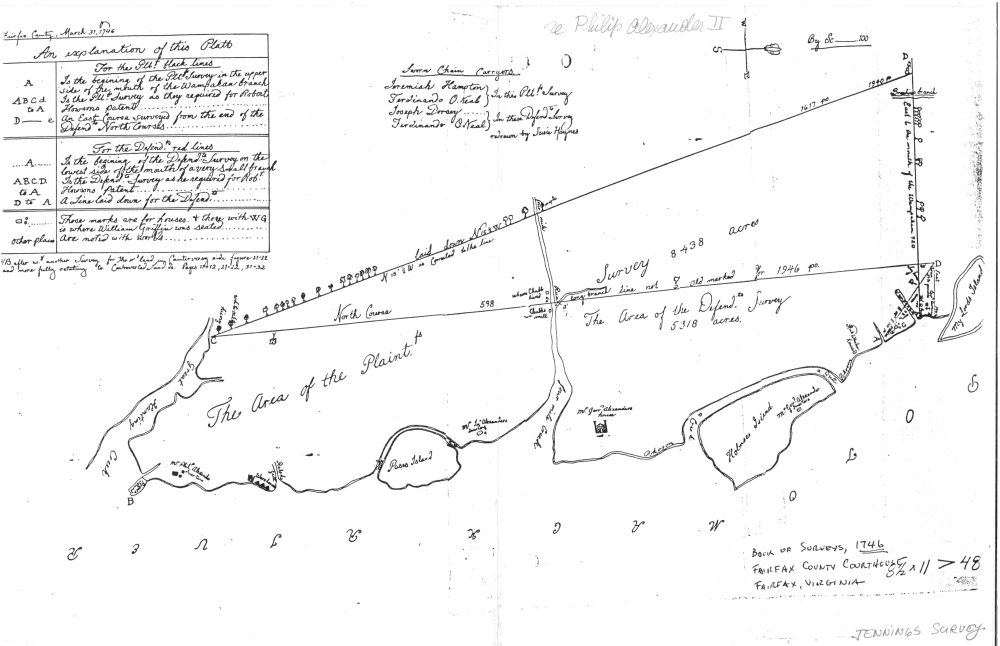

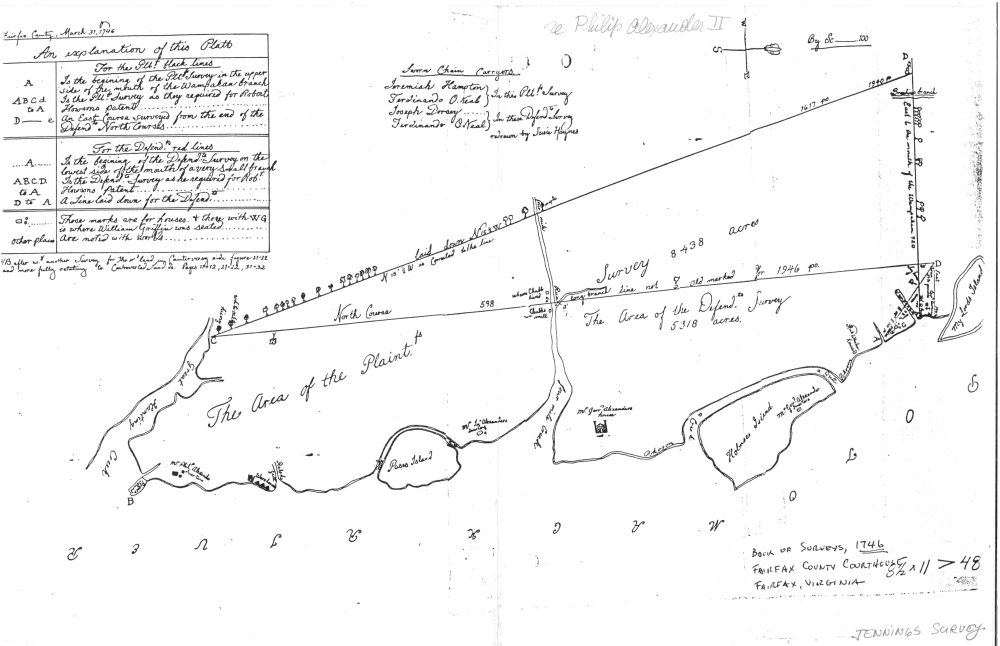

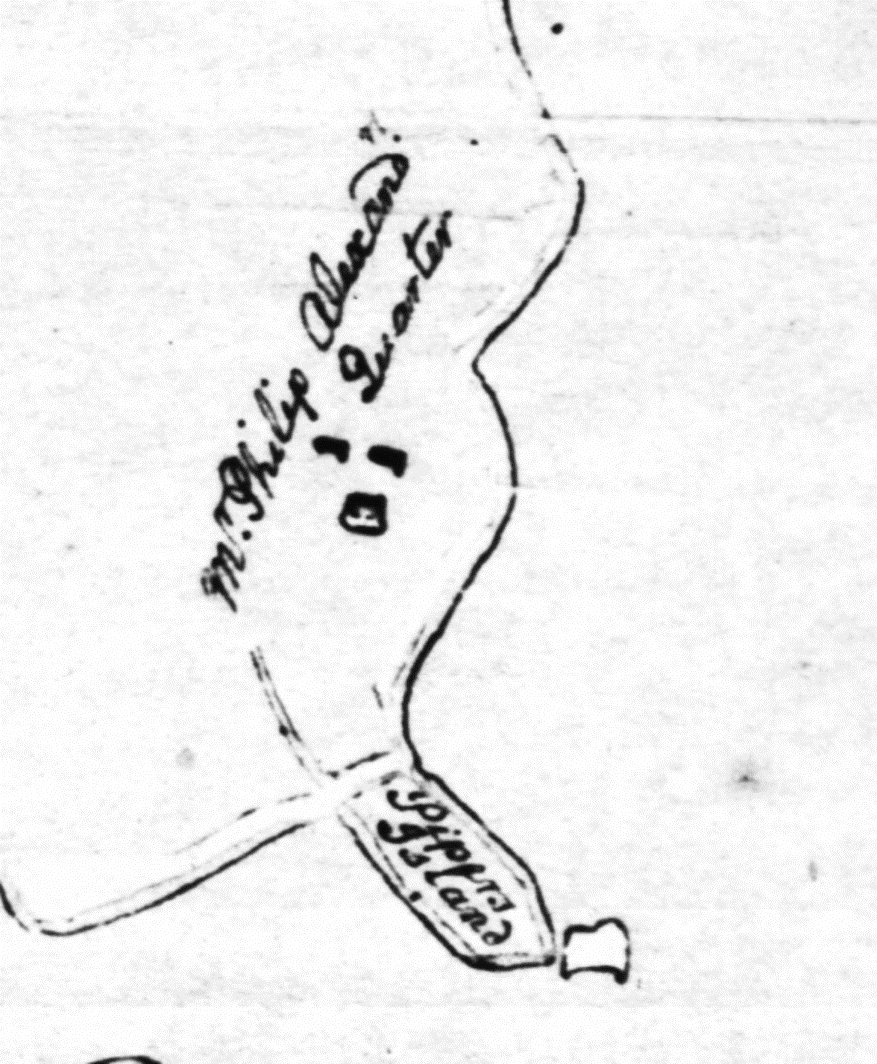

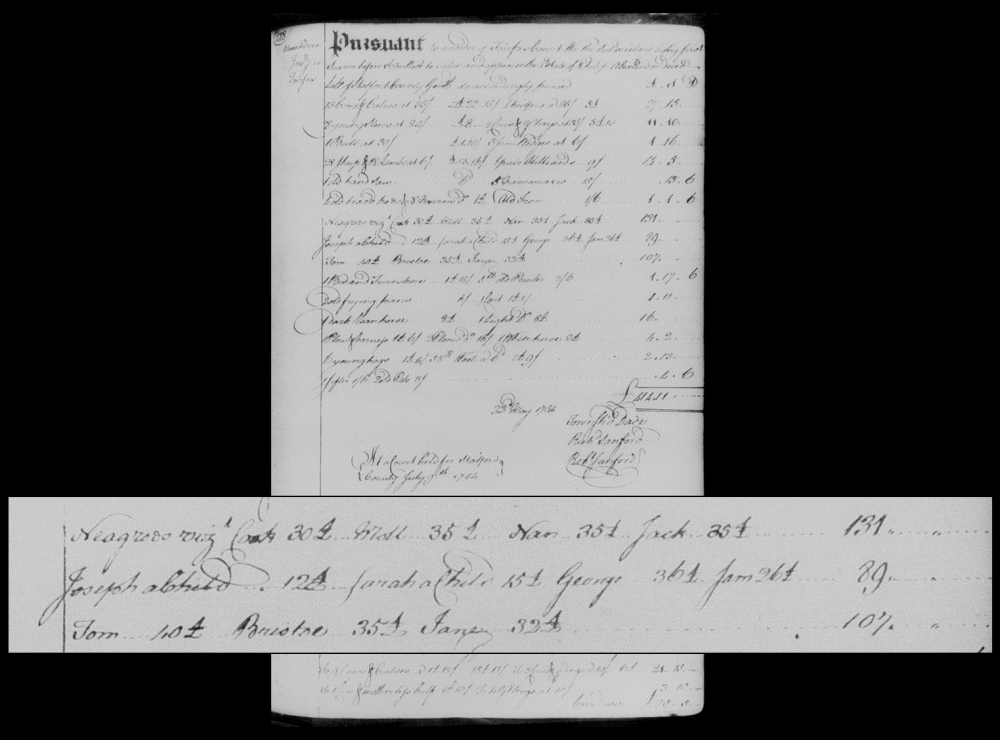

This stop takes its title from a 1746 map showing the location of “Mr. Philip Alexander’s Quarters,” somewhere along the ridge about a block to the west of here.[1] The map label refers not to the people who lived in these dwellings, but instead to the enslaver and owner of the majority of the land on which Alexandria was originally founded. People including Co[ati], Moll, Nan, Jack, Joseph, Sarah, George, Sam, Tom, Bristoe, and Jane may have carved out lives in these dwellings or quarters as they cleared this land, and planted, tended, and harvested the tobacco, which made Alexander’s wealth.

Prior to the founding of Alexandria in 1749, a public tobacco warehouse was already located at the site of the future town.[2] The colonial legislature authorized a warehouse near Great Hunting Creek in 1730 to help regulate the market for tobacco and prevent “the exportation of all trash, bad, unsound, and unmerchantable tobacco.”[3] The original location, south of Great Hunting Creek, was found to be “very inconvenient,” and a new site was selected in 1732. This warehouse, near what is now the foot of Oronoco Street, is depicted on Washington’s 1748 map of town site and was one of a number of inspection stations along Virginia’s waterways for tobacco exported out of the colony. [4] Tobacco was the central commodity of the early Virginia economy, and the presence of a tobacco warehouse here on the upper Potomac River reflects the extent of European settlement and tobacco cultivation by the beginning of the 1740s.

Tobacco is a labor-intensive crop. Initially, farmers turned to predominantly white indentured laborers bound to work for a set number of years in exchange for passage to Virginia. However, by the turn of the 18th century, Virginians increasingly relied on race-based chattel slavery as the primary source of their agricultural labor.[5]

Philip Alexander II (1704-1753) owned property in what was then Fairfax County, including approximately 500 acres of land, situated between the Potomac River, Great Hunting Creek, Hooffs Run, and a line near what is today Cameron Street

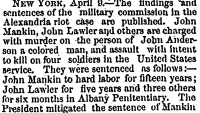

We know the names of those forced to live in these buildings and cultivate the land based on an inventory taken at the time of Alexander's death in 1753.[6] Included in this inventory is a list entitled “Alexander’s Inventory in Fairfax,” which names eleven enslaved people who lived at Alexander’s quarters.

The number next to each name is the value in pounds at which each was assessed as a part of Alexander’s estate. Because these enslaved Africans or African Americans were legally the property of Alexander, the county required them to be included in this inventory, appearing on the list between an “Old Iron” and a “Bed and Furnitures.”

Though we know very little about them, these eleven people are among Alexandria’s earliest residents of African descent.

Stop 13: Footnotes

[1] “Record of Surveys, 1742-1856,” Fairfax County, VA, 39-42, accessed December 30, 2021, FamilySearch.org. For similar surveys, see 20-22, 63-67, 74-75.

[2] Diane Riker, “Alexandria and Belhaven: A Case of Dual Identity” (Alexandria: Office of Historic Alexandria, 2009), accessed December 18, 2021.

[3] General Assembly, “An Act for amending the Staple of Tobacco; and for preventing Frauds in his Majesty’s Customs,” 1730, Encyclopedia Virginia, accessed December 18, 2021.

[4] Virginia and William Waller Hening, “An Act to amend and explain the Act, for amending the Staple of Tobacco; and for preventing Frauds in his Majesty’s Customs, May 1732,” The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, From the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, vol. 4 (Richmond: Franklin Press–W. W. Gray, Printer, 1820), 329-340.

[5] Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 109-141.

[6] Stafford County Deed Book O-282-8, Stafford County Circuit Court Land Records, Stafford, VA.

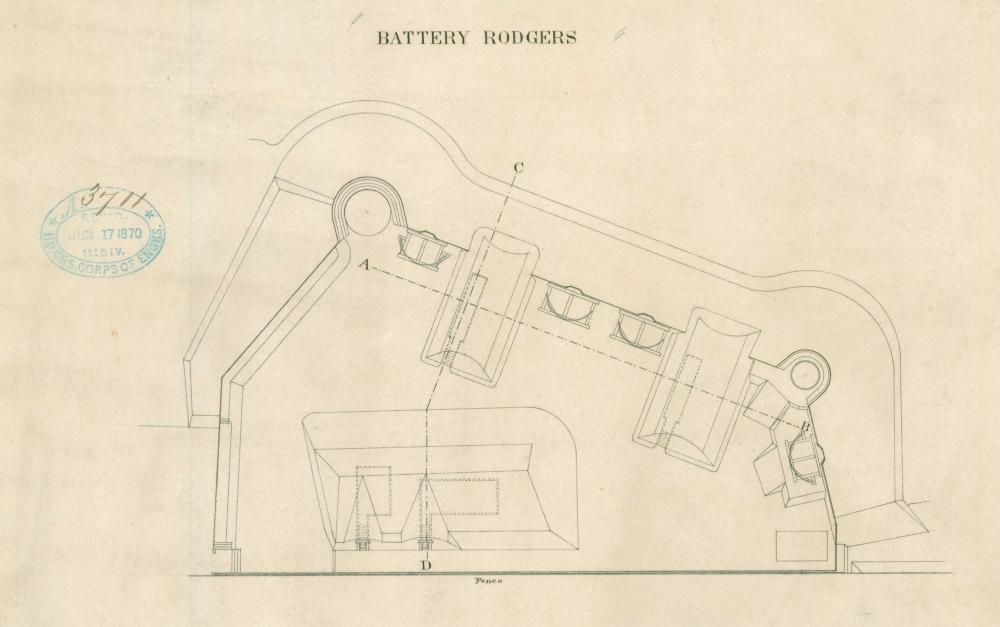

Stop 14: USCT at Battery Rodgers

Sign on Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park

19th Century

Battery Rodgers was one of the 68 major forts and batteries that circled Washington, D.C. during the Civil War. Built in 1863, it was designed to defend the river approach to Alexandria and Washington, D.C. along with Forts Foote and Washington, located several miles downriver on the Maryland side of the Potomac.[1] For part of the war, Battery Rodgers garrisoned a company of soldiers from the United States Colored Troops (USCT), segregated regiments of African Americans in the Union Army.[2] Their experiences show the continual fight for freedom and equality in the tumultuous post-War period.

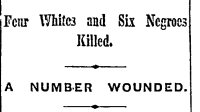

These USCT soldiers were here on Christmas Day 1865, more than eight months after the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox, when racial violence broke out across Alexandria in what were called the Christmas Riots.[3] In multiple incidents throughout the city, groups of white Alexandrians, many of whom were returning Confederate veterans, attacked African Americans as they celebrated the first Christmas following the Civil War. At least one African American man, John Anderson, was killed and many others, including several soldiers stationed at Battery Rodgers, were injured.[4] The military was called out, and the white perpetrators were arrested and sent to the military prison at the former slave jail of Price, Birch & Co. at 1315 Duke Street (one of the slave dealers located there after Franklin & Armfield).[5]

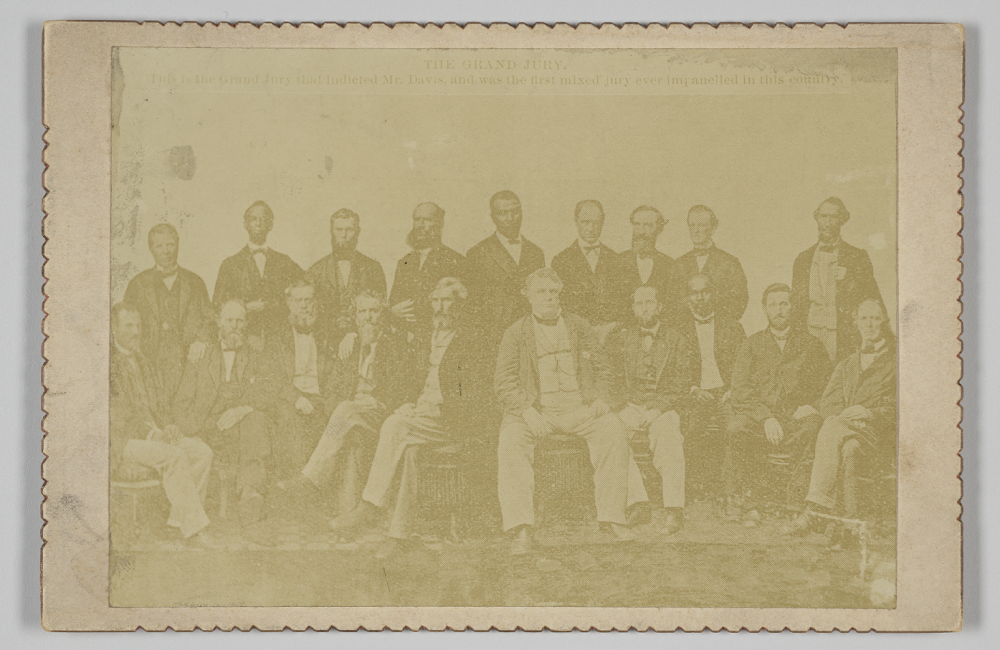

As they were arrested and held by the military, a U.S. Military Commission heard charges against 17 white men for their roles in the riots.[6] “The intent of the accused,” military prosecutors later argued in court, “was a general onslaught on negroes.”[7] Guilty verdicts were secured against five of the men for assault and battery with intent to kill and one of these was charged with murder. This last charge carried with it a 15-year sentence of hard labor in the federal penitentiary at Albany, New York, which was commuted to five years.[8] These men were released less than two months into their sentences on the grounds that the military commission was not a civilian court and did not have the jurisdiction to try them. No charges were filed in civilian court following their release.[9]

Stop 14: Footnotes

[1] Benjamin Franklin Cooling, III and Walton H. Owen, II, Mr. Lincoln’s Forts: A Guide to the Civil War Defenses of Washington (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing, 1988), viii, 45-47.

[2] “From Washington,” Willimantic Journal (Willimantic, CT) December 28, 1865.

[3] Ibid; “Rioting at Alexandria, VA,” New York Tribune December 27, 1865, 1; “The Riot in Alexandria,” Baltimore American December 28, 1865, 4; “Christmas Day in Alexandria –the Negro ‘Insurrection,’” New York Tribune December 29, 1865, 1; “Riot in Alexandria,” Staunton Spectator and Vindicator January 2, 1866, 3.

[4] “Alexandria Riot,” Richmond Daily Whig December 29, 1865, 2; “The Christmas Insurrections,” Dover Enquirer January 4, 1866, 2.

[5] “The Alexandria Riot,” New York Tribune December 28, 1865, 1; “The Disturbances in Alexandria,” Norfolk Post December 29, 1865, 2.

[6] Detailed summaries of the proceedings of the Military Commission were published in the Alexandria Gazette under the heading “The Military Commission” almost daily between January 10, 1866 and February 20, 1866.

[7] “The Military Commission,” Alexandria Gazette February 19, 1866, 3.

[8] “Local News”, Alexandria Gazette April 7, 1866, 3.

[9] “Local News,” Alexandria Gazette June 4, 1866, 3; “Before Samuel Nelson, a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States,” Alexandria Gazette June 5, 1866, 3.

Stop 15: CCC Camp at Battery Cove

Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park

20th Century

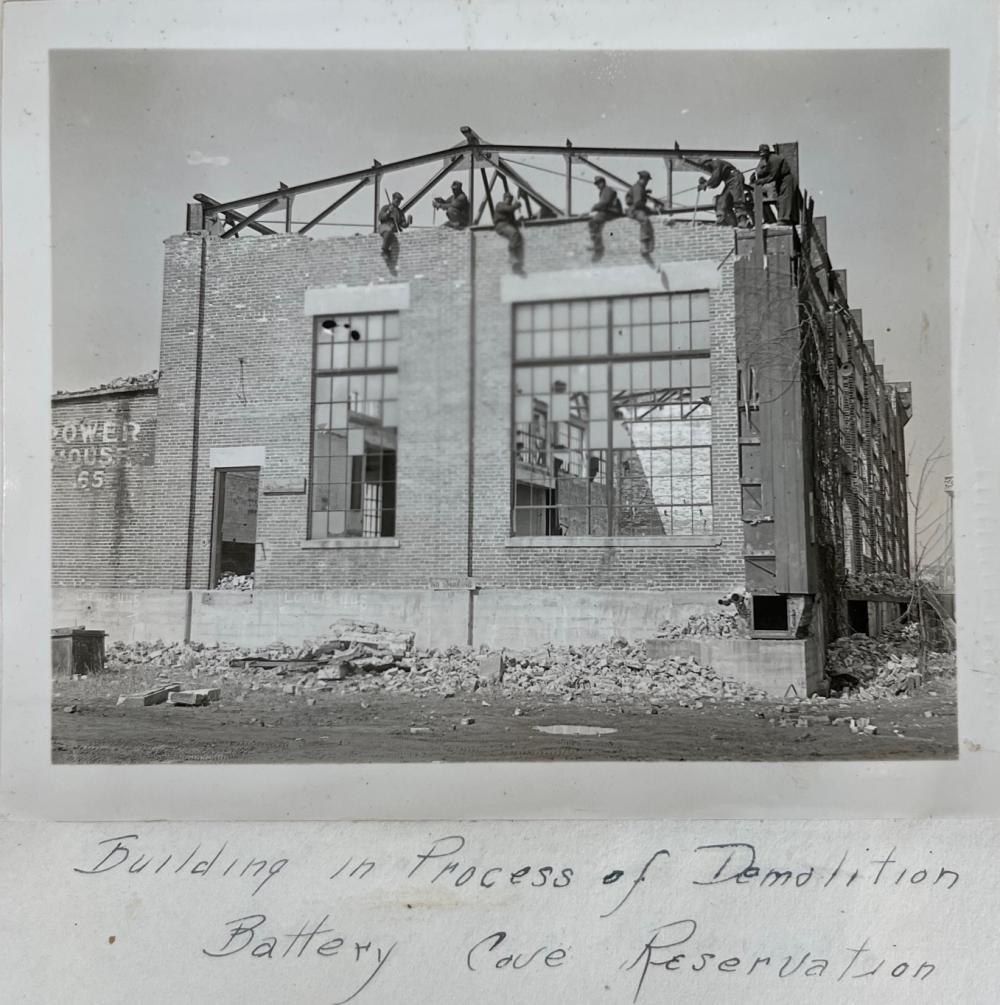

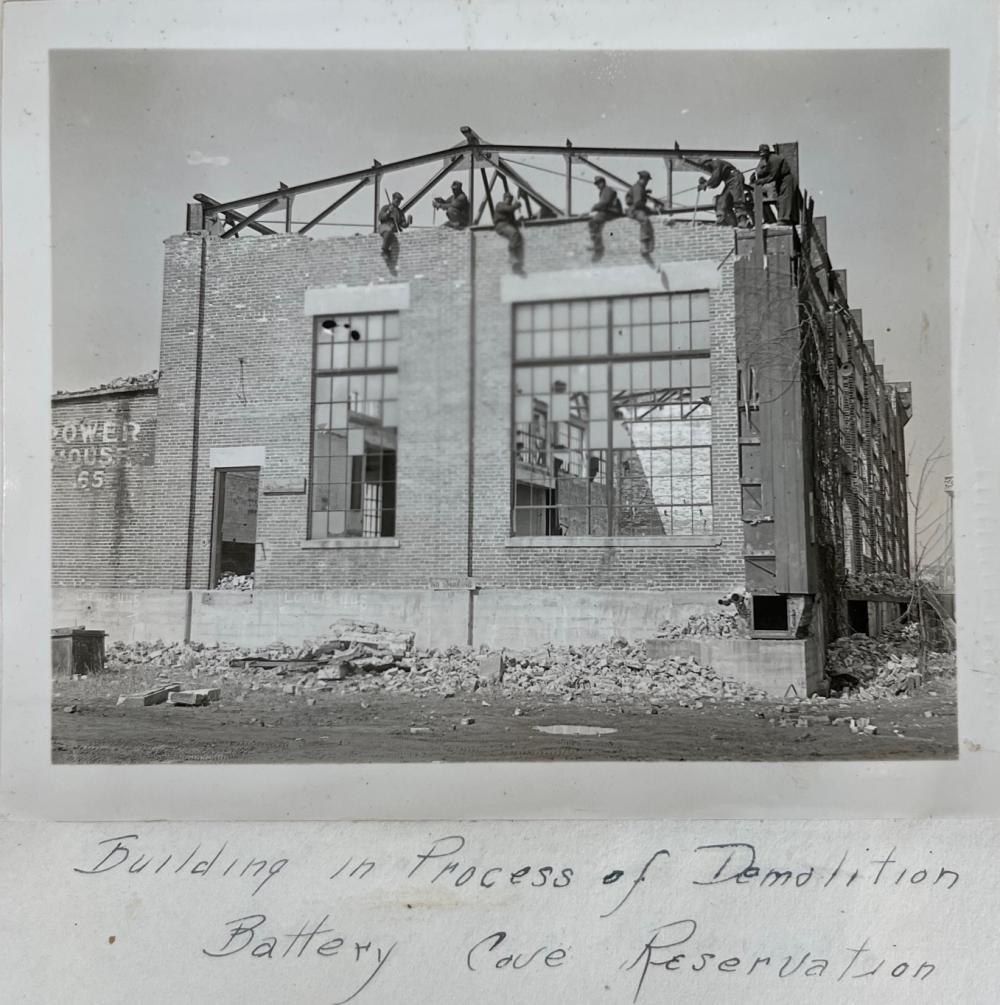

In 1933, the federal government created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a New Deal program that hired unemployed and unmarried men between the ages of 17 and 28 to work on public projects. One such endeavor was to convert Battery Cove into a park, complimenting the soon to be completed George Washington Parkway. Previously, the federal government had created most of the land that became Battery Cove with dredged soil from the Potomac River in 1912, and the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation used the area for the construction of ships during World War I. With the bankruptcy of the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation in 1921, the property remained vacant except for a radio receiving station for the military.[1]

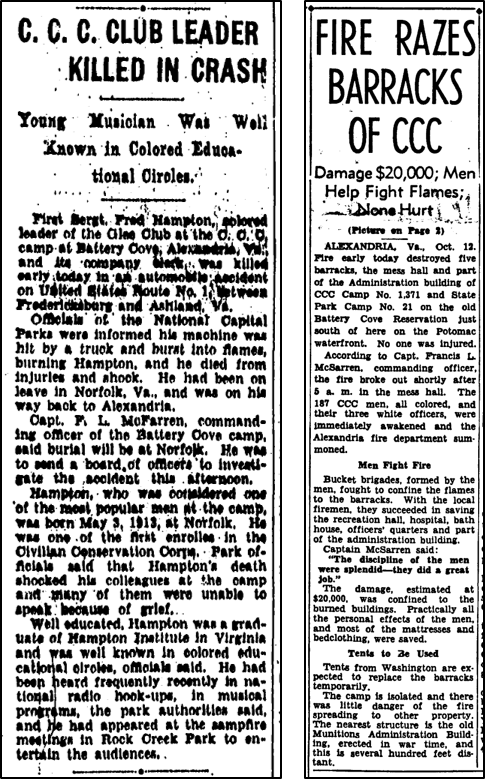

In 1935, the CCC created a camp at Battery Cove, which housed between 170 to 200 African American men. Their job was to tear down abandoned buildings, construct a road with leftover bricks and concrete on the site, remove oily soils, and begin plowing and seeding.[2] In their free time, the men, almost all of whom came from the Tidewater region of Virginia, took night classes at the Parker-Gray School, attended religious services organized by local churches, and participated in athletic competitions and music programs.[3] The camp was especially known for its glee club, called the CCC Glee Club or the Battery Cove Civilian Conservation Corps Southern Spiritual Singers, which gained national acclaim under the direction of conductor Fred Hampton. In April 1935, the club performed on NBC’s Blue Network (an early radio broadcasting company) as part of a program organized by the National Park Service with the U.S. Marine Band. Edgar G. Brown, a reporter with Norfolk’s News Journal and Guide, believed that they were “perhaps the first group” of African American young men “given a nation-wide audience over the National Broadcasting Blue Network.”[4]

Tragedy, however, soon led to the demise of Alexandria’s Battery Cove CCC Camp. In June 1935, Fred Hampton died in a car crash along Route 1 between Richmond and Fredericksburg while returning to the camp from Norfolk.[5] A few months later, almost the entire camp burned down under mysterious circumstances. The Alexandria Gazette reported that a fire started in the kitchen while the night watchman tried to cook himself breakfast. Although workers saved their clothing, mattresses, bedding, and a piano, five barracks, the kitchen, and half of the supply house burned to the ground. Within hours of the fire, Virginia’s CCC headquarters in Richmond ordered that the men leave Alexandria immediately for Virginia Beach.[6]

The men left Alexandria without completing their work. Battery Cove remained in the War Department’s possession as a radio receiving station through World War II.

Stop 15: Footnotes

[1] “Supplement Report: U.S. Army Reserve Training Headquarters: Survey and Evaluation” (Baltimore: U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, Office of Planning and Program Development, 1996), 12-13.

[2] Record Group 79, Entry 95, Box 137; National Archives, College Park, MD.

[3] “Tidewater Boys in Majority at Camp,” New Journal and Guide (Norfolk, VA), March 2, 1935.

[4] Edgar G. Brown, “Fred Hampton Directs Glee Club of CCC Company 1371 in Park Service Broadcast,” New Journal and Guide (Norfolk, VA), April 13, 1935. See also “VA. CCC Units at Directors’ Testimonial,” New Journal and Guide (Norfolk, VA), April 6, 1935; “Campfire Program to be held Tonight,” Evening Star (Washington, DC) May 10, 1935.

[5] “Fred Hampton is Killed in Virginia Auto Crash,” Washington Post June 13, 1935.

[6] “CCC Camp Here is Destroyed by Fire,” Alexandria Gazette October 12, 1935; “Six CCC Shacks Razed by Blaze at Alexandria,” Washington Post October 13, 1935.

Stop 16: African American Workers at the Virginia Shipbuilding Company

Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park

20th Century

In the late 1910s, employment opportunities in Alexandria for African Americans expanded in response to American mobilization during World War I. The waterfront became integral to the war effort, most notably with the establishment of a shipyard by the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation. In 1917, the U.S. Shipping Board, which was established to expand the country’s wartime merchant fleet, entered a contract with Connecticut-based Groton Iron Works, under the name Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation. The contract included the construction of 12 iron-clad, steam-powered supply ships, each costing over $1.5 million. At its height, the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation employed up to 3,000 men, including a sizable number of African Americans.[1] Because Alexandria’s workforce remained segregated throughout World War I, African American men were often relegated to the lowest paying, most labor-intensive positions at the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation. Based on World War I draft cards, the majority of African Americans were common laborers.[2] For example, Charles Collier, a recent arrival from Georgia, worked as a laborer and roomed in the Smith household a few blocks away.[3] A handful of men, however, were hired for specific positions. Lorenzo Chase, who worked as a plasterer, obtained a position as a cement finisher at the shipyard, which translated into other jobs in the 1920s and early 1930s.[4] Ernest Green, a native Alexandrian, worked at the shipyard as a chauffeur.[5]

When the war ended on November 11, 1918, the shipyard had not launched a single vessel. Nevertheless, it continued to operate and completed ten ships in the next two years to be used for peacetime purposes. At the same time, a Congressional investigation revealed that the owners had misappropriated federal funds, leading to several indictments. The company filed for bankruptcy in 1921.[6] With the Virginia Shipbuilding Company’s bankruptcy, the federal government contracted the shipyard to Western Marine and Salvage Company to scrap some of the U.S.’s wartime fleet.[7]

Stop 16: Footnotes

[1] “Lease Shipyard Site,” Alexandria Gazette December 21, 1917; “Building the Ships,” Alexandria Gazette June 12, 1918. See also Alice C. Crampton, Supplemental Report: U.S. Army Reserve Training Headquarters: Survey and Evaluation (Fairfax, VA: Parsons Engineering Science Inc., March 1996), 4-6.

[2] World War I Draft Cards, 1917-1918; accessed July 21, 2019, Ancestry.com.

[3] 1920 U.S. Census, Alexandria, VA, Ward 3, 2A; Charles Collier, Serial Number 3157, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918; accessed December 28, 2020, Ancestry.com.

[4] Lorenzo Chase, Serial Number 3796, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918; Alexandria Virginia Directory (Alexandria: Hill Directory Co., Inc., 1917), 149; Alexandria Virginia Directory (Alexandria: Hill Directory Co., Inc., 1918), 153; 1930 U.S. Census, Alexandria, VA, Enumeration District 101-10, 14B; accessed December 28, 2020, Ancestry.com.

[5] Earnest [Ernest] Greene [Green], Serial Number 2095, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918; 1920 U.S. Census, Alexandria, Virginia, Ward 4, 2A; Ernest Green, Serial Number 1087, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942; accessed December 28, 2020, Ancestry.com.

[6] “Morse Charges Denies,” Alexandria Gazette April 26, 1920; “Grand Jury to Probe Morse Ship Deals,” Alexandria Gazette November 30, 1921. See Crampton 4-6.

[7] “Start Alexandria Ship Work Monday,” Washington Post October 14, 1922.

Stop 17: Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge and Freedmen’s Cemetery

Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park

20th Century

Above you is the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge, named for President Woodrow Wilson, a Virginia native. The original span of the bridge (as well as the first portions of the Capital Beltway) opened in 1961. The subsequent growth of Washington, D.C. and its surrounding suburbs, including Alexandria, led to increased use, frequent congestion, and deterioration of the bridge. In 1988, Virginia, Maryland, Washington, D.C., and the Federal Highway Administration began studying ways to increase the bridge’s capacity and address structural concerns with the existing span.[1]

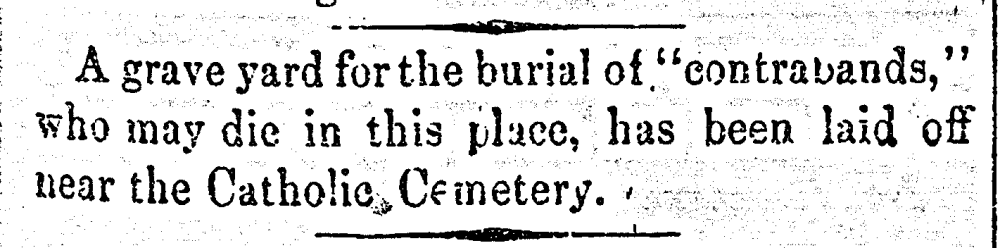

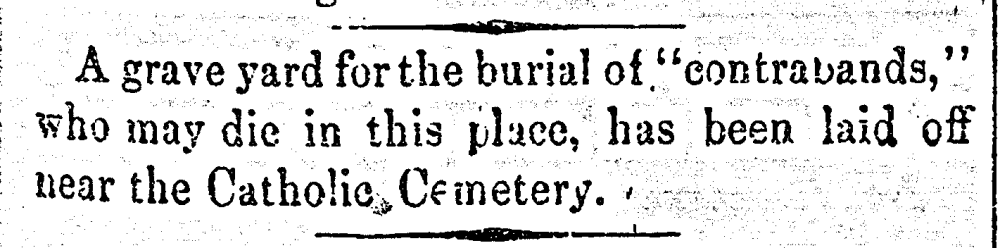

Around the same time that plans to improve and expand the Wilson Bridge began to develop, City of Alexandria Historian T. Michael Miller discovered late 19th-century newspaper articles describing a cemetery at the south end of town established for African American refugees during the Civil War. Based on this information, Alexandria Archaeology included Freedmen’s Cemetery in the Virginia survey of abandoned cemeteries in 1989. A few years later, Historian Wesley Pippenger found and transcribed the “Book of Records,” a list of the names of individuals interred at the cemetery.[2] This initial work re-established the location of the sacred ground at the south end of Washington Street, despite over a century of neglect and desecration, including the construction of a gas station and office building on the site.

Citizen activists played a major role in reclaiming the burial site as a memorial to the 1,711 men, women, and children known to be laid to rest there. A Washington Post article in 1997 entitled, “Cemetery Prompts Questions on Bridge: Freedmen’s Graves Could Affect Wilson Plan,” publicly announced that researchers contracted by state and federal officials had found evidence of burial features still preserved at the site.[3] Lillie Finklea, who had read the article, partnered with Louise Massoud to form the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery to raise awareness of the site’s history and to ensure that it received the respect that it deserved.

You can hear the frustration in Finklea’s voice in the early years of her preservation work. In a 1999 interview with the Alexandria Journal, Finklea implored: “People in this city have paved over almost everything that is important to the Black community. We have to hold on to what is left.”[4] Initial efforts of the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery focused on an annual proclamation and wreath-laying event as part of a Week of Remembrance, “in memory of the African American slaves who sought haven in our City and their descendants and those who seek freedom from injustice throughout the world.”[5] The Friends organization also sought to erect a historic highway marker, which stands today, and develop an exhibit, website, and brochure.

In a 2005 interview with Finklea, she referenced the “Book of Records,” which lists the names of the freedmen and women buried in the cemetery, and remarked, “[a] lot of the names in that book are families that I know.” The Freedmen’s Cemetery Descendants’ Project began in 2008 led by Char McCargo Bah, the official City Genealogist for the cemetery. She sought out descendants of those buried in the cemetery in Alexandria and across the country. Today, over 1,000 descendants of Freedmen’s Cemetery have been identified through this research.[6]

The Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery’s advocacy for the historic site continued as the vision grew to create a City-owned memorial park that would simultaneously protect the burials and honor those who sought freedom from slavery during the Civil War. The Friends successfully proposed that the City of Alexandria purchase the entire cemetery and develop a set of guiding principles for the memorial.[7] Today, you can visit the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial, dedicated in 2014, and witness the culmination of the tireless efforts of the Friends of Freedmen’s Cemetery and the many partners who contributed to the project. During its dedication ceremony, Finklea looked around in wonder, “It’s unbelievable. I can’t believe all of these people are here.”[8] Lillie Finklea and Louise Massoud were honored as Living Legends of Alexandria in 2009.[9]

Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial can be visited at 1001 South Washington Street.

Stop 17: Footnotes

[1] Woodrow Wilson Bridge in Maryland and Virginia: FHWA Leads the Planning Process for Bridge Redesign (Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 2010), accessed December 18, 2021.

[2] Wesley E. Pippenger, Alexandria, Virginia Death Records, 1863-1869 (The Gladwin Record) and 1869-1896 (Westminster, MD: Family Line Publications, 1995).

[3] Alice Reid, “Cemetery Prompts Questions on Bridge,” The Washington Post, January 30, 1997, accessed December 18, 2021.

[4] Stephen Henn, “Reviving Lost History, Group Recalls Civil War-era Freemen’s Cemetery,” The Alexandria Journal, June 1, 1999.

[5] Pamela Cressey, “A New Tradition Honors the Memory of Black Americans ,” Alexandria Gazette June 12, 1997, accessed December 18, 2021.

[6] Char McCargo Bah, Alexandria’s Freedmen’s Cemetery: A Legacy of Freedom (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2019).

[7] Pamela J. Cressey and Natalie Vinton, “Smart Planning and Innovative Public Outreach: The Quintessential Mix for the Future of Archaeology,” in Past Meets Present: Archaeologists, Partnering with Museum Curators, Teachers, and Community Groups, edited by John H. Jameson and Sherene Baugher (New York: Springer, 2007), 393-410.

[8] Robert Samuels, “A Memorial Honors Slaves who Escaped the South for Refuge in Alexandria, Va.,” The Washington Post, September 6, 2014, accessed December 19, 2021.

[9] “Lillie Finklea and Louis Massoud,” Living Legends of Alexandria, accessed December 18, 2021.

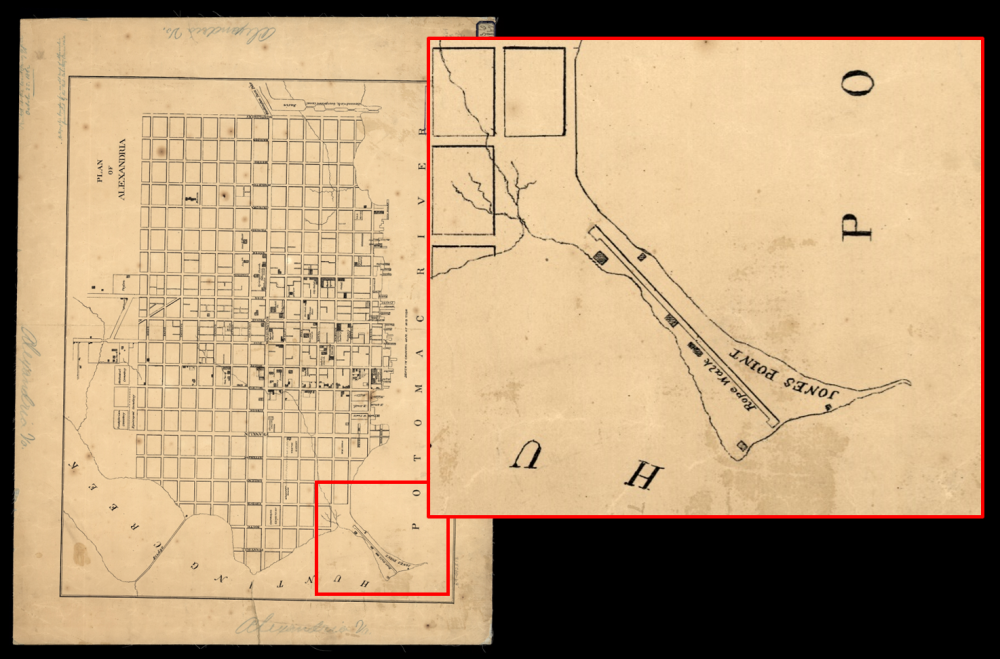

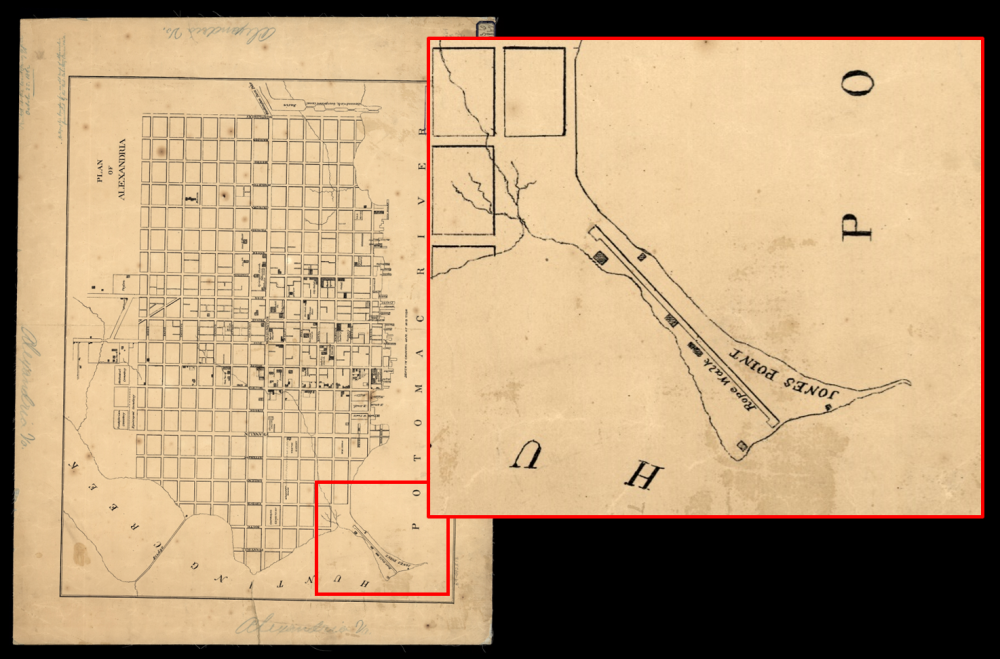

Stop 18: Jones Point Ropewalk

Sign on Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park

18th and 19th Century

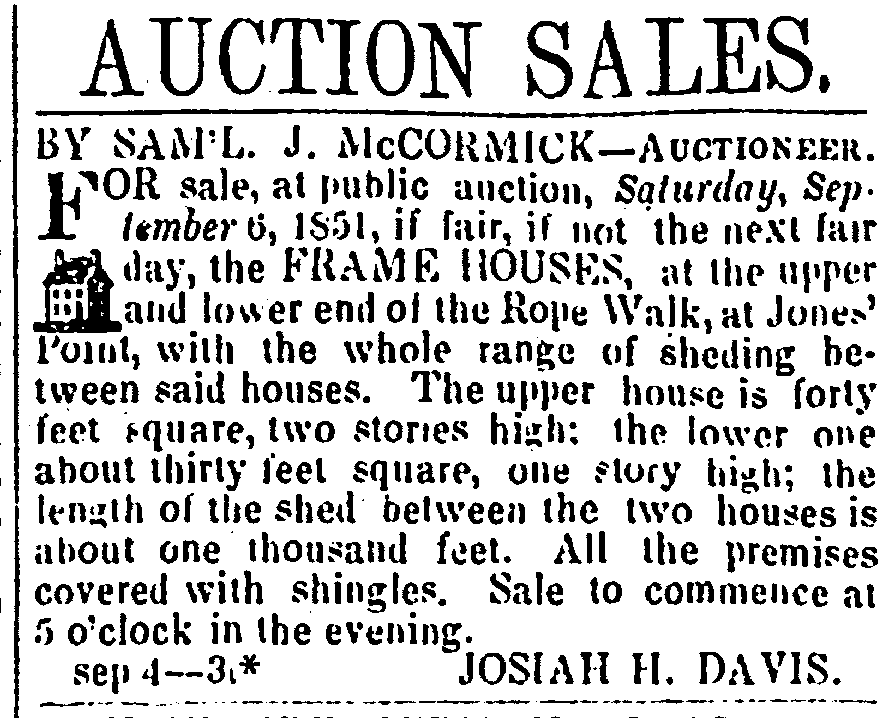

Alexandria once operated as a thriving port town and center of maritime activity. Trades and industries associated with Alexandria’s seaport grew in the 18th and 19th centuries and relied on the labor of free and enslaved Black Alexandrians. One of these industries was the manufacturing of rope for ships’ rigging, an essential business in busy port cities. Before the invention of steam power, rope was made in long, purpose-built structures called “ropewalks.” It was a physically demanding process.[1]

There may have been a ropewalk near Alexandria (location unknown) as early as 1775 when George Washington purchased rope for his brig Farmer from William Hepburn, a prominent Alexandria merchant and owner of a ropewalk.[2] The town’s first known ropewalk is mentioned in an advertisement placed by James Irvin in 1794 describing the best quality cordage and white rope available either at Irvin’s store or the ropewalk itself. Two years later, a newspaper advertisement again placed by Irvin for the sale of his ropewalk captures a glimpse into who performed the labor of making rope. He notes that the sale of the ropewalk comes with a “term of servitude of several Blacks, who are good Rope-makers.”[3] Irvin may have been referring to enslaved men apprenticed in the trade of rope making who would receive their freedom after a specified term. Newspapers also recorded at least 10 white ropemakers working in Alexandria over the next 25 years.[4] One of them, Joseph Harper, advertised for the return of an enslaved man named Guss, a ropemaker by trade who had run away or self-emancipated himself from Harper’s ropewalk.[5]

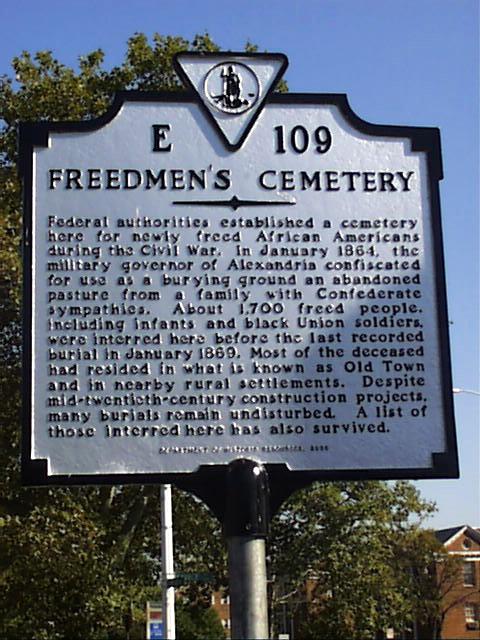

Josiah Davis operated one of the largest ropewalks in the Chesapeake region at Jones Point from 1833 to 1850.[6] Davis built a 1,300 foot-long, two-story building for his operation. The landform and location of Jones Point provided an ideal location for a ropewalk with lots of out-of-the-way open space and less disruption from city life. In August 1833, Davis advertised “to hire eight or ten good spinners of steady habits.”[7] The “spinner” walked backwards the length of the building between two reels, unwinding lengths of hemp from around his waist and spinning the fiber in each hand to create rope. He might walk 20 miles in a 10-hour workday.[8] Like other early industries in Alexandria, ropewalks relied on both Black and white labor. Researchers believe that free Black men Richard Madella, Charles Guss, William Cupid, and Isaac Clark may have lived in Davis’s household at 213 South Pitt Street and worked at his ropewalk.[9] Archaeological excavations at Jones Point before the construction of the Wilson Bridge also discovered the only known physical traces of this once thriving maritime industry. At this site, archaeologists recorded and excavated rows of large postholes with the ground between them stained, probably from tar, used to keep the rope from rotting.[10]

In 1859, American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow captured the art of rope making in his poem, “The Ropewalk:”

In that building, long and low,

With its windows all a-row,

Like the port-holes of a hulk,

Human spiders spin and spin,

Backward down their

Threads so thin

Dropping, each a hempen bulk.[11]

Longfellow wrote this poem a few years after the ropewalk at Jones Point closed. Based on U.S. Census records and newspaper advertisements, ropemaking ended in Alexandria around 1850, and the ropewalk was sold off in sections in September 1851.[12]

Stop 18: Footnotes

[1] William P. Barse, Jeffery Harbison, Ingrid Wuebber, and Meta Janowitz, Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project Phase III Archeological Mitigation of the Prehistoric and Historic Components of Site 44AX185, Jones Point Park, Alexandria, VA” (unpublished report, URS Corporation, prepared for Federal Highway Commission, Virginia Department of Transportation, and the National Park Service, December 2006).

[2] “The Diaries of George Washington,” April 1775, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed December 18, 2021.

[3] [Advertisement], Columbian Mirror and Alexandria Gazette, March 12, 1796.

[4] T. Michael Miller, comp., Artisans and Merchants of Alexandria, VA, 1784-1820, vol. 1 and 2 (Berwyn Heights, MD: Heritage Books, 1991).

[5] Miller, comp., Artisans and Merchants of Alexandria, VA, 1784-1820, vol. 1, 185-186; [Advertisement], Times; and District of Columbia Daily Advertiser Dec 12, 1798.

[6] Donald Shomette, Maritime Alexandria: An Evaluation of Submerged Cultural Resource Potentials at Alexandria, Virginia (Alexandria: Alexandria Archaeology, 1985), 178.

[7] “Rope Makers Wanted,” Alexandria Gazette August 28, 1833.

[8] Barse et al., 3.25.

[9] Barse et al., 3.26-3.27.

[10] Barse et al., 5.1-5.9.

[11] “The Long Story of the Jones Point Ropewalk, 1833-1850,” The Historical Marker Database, accessed December 28, 2021.

[12] Barse et al., 3.30; U.S. Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880, Town of Alexandria and Fairfax County, Products of Industry, 359-363, 553, accessed February 10, 2022, ancestry.com. “Auction Sales,” Alexandria Gazette September 4, 1851; “Local Items,” Alexandria Gazette September 9, 1851; “Auction Sales,” Alexandria Gazette September 15, 1851.

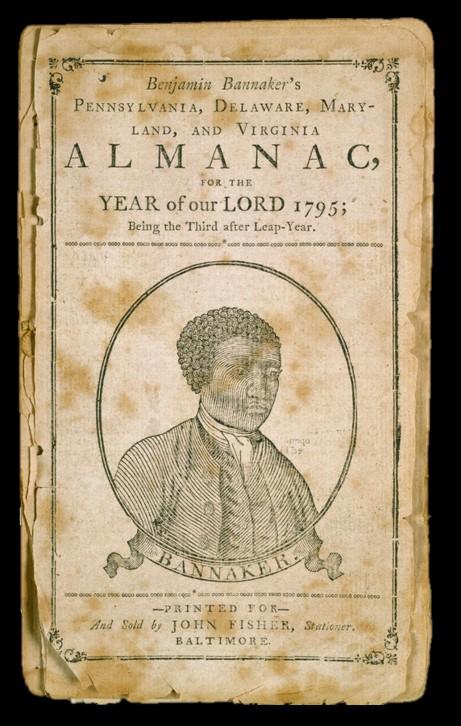

Stop 19: Jones Point and Benjamin Banneker

Jones Point Lighthouse, Mount Vernon Trail, Jones Point Park

18th and 19th Century

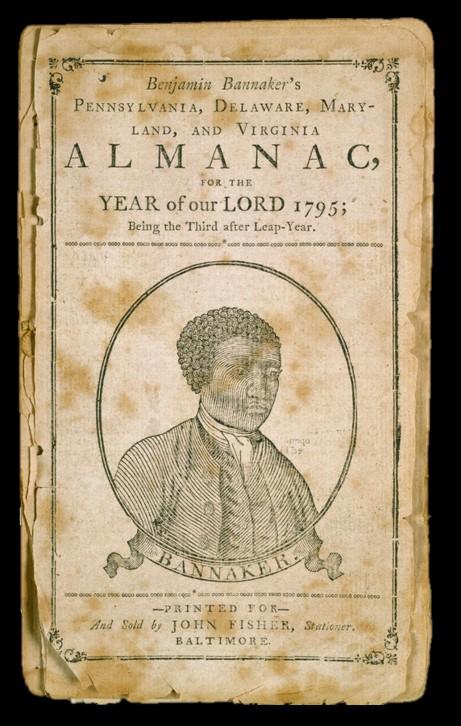

In 1791, the Residence Act authorized President George Washington to locate and survey a site for the “permanent seat of the government of the United States… not exceeding ten miles square [or 100 square miles].”[1] For this job, Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State, selected Major Andrew Ellicott, a surveyor, for the project. Ellicott, in turn, hired Benjamin Banneker (1731-1805), a highly accomplished writer, inventor, and free African American from Maryland. Banneker was given the job of making the “astronomical observations and calculations” to establish the “south corner” of the new capital city. To make this calculation, he lay on his back in an observation tent and plotted the course of six stars as they crossed his location at specific times, thereby determining the exact location of the southernmost “boundary stone.” The first and southernmost point of the new federal district was established at Jones Point, and its boundaries included the busy ports of Alexandria, Virginia and Georgetown, Maryland. In 1801, both ports became part of the newly-formed District of Columbia and placed under federal jurisdiction with the passage of the District of Columbia Organic Act.[2] Banneker’s many other contributions to the development of the newly seated capital included recreating, from memory, the plans for the new federal city when Pierre L’Enfant quit the job and departed the United States, taking his plans with him.[3] The cornerstone under you was laid in a ceremony on April 15, 1791.[4]

1791 was a busy year for Banneker. In addition to positioning the boundary stone, Banneker completed work on his first Almanac, which included motions of the sun, moon, and planets; weather; holidays; court days; road mileage; currency exchanges; and “useful tables” such as tide charts.[5]

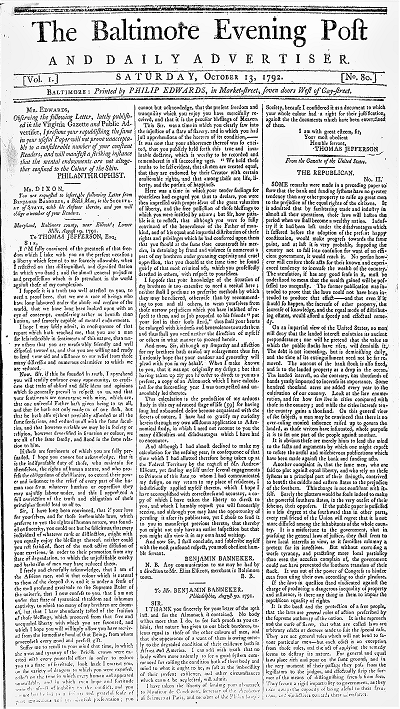

Banneker sent a copy of his Almanac to Thomas Jefferson, accompanied by a heartfelt letter.[6] Banneker, a man of strong moral conviction, deeply opposed slavery and characterized it as “inhuman[e] captivity.” His letter particularly noted the inconsistency of Jefferson’s position; Jefferson was both a slaveholder and author of the Declaration of Independence, which provided that “all men are created equal.” In his response to Banneker, Jefferson acknowledged “the ability of a Black man to exhibit extraordinary intellect,” but largely avoided the substance of Banneker’s letter and the uncomfortable position in which it put him.[7]

Banneker’s 1791 letter, an excerpt of which is inserted below, speak to his views on the contradictions surrounding the founding of the United States and slavery:

Sir, I have long been convinced, that if your love for your Selves, and for those inesteemable laws which preserve to you the rights of human nature, was founded on Sincerity, you could not but be Solicitous, that every Individual of whatsoever rank or distinction, might with you equally enjoy the blessings thereof, neither could you rest Satisfyed, short of the most active diffusion of your exertions, in order to their promotion from any State of degradation, to which the unjustifyable cruelty and barbarism of men may have reduced them….

Sir, Suffer me to recall to your mind that time in which the Arms and tyranny of the British Crown were exerted with every powerful effort in order to reduce you to a State of Servitude, look back I intreat you on the variety of dangers to which you were exposed, reflect on that time in which every human aid appeared unavailable, and in which even hope and fortitude wore the aspect of inability to the Conflict, and you cannot but be led to a Serious and grateful Sense of your miraculous and providential preservation; you cannot but acknowledge, that the present freedom and tranquility which you enjoy you have mercifully received, and that it is the peculiar blessing of Heaven.

This Sir, was a time in which you clearly saw into the injustice of a State of Slavery, and in which you had just apprehensions of the horrors of its condition, it was now Sir, that your abhorrence thereof was so excited, that you publickly held forth this true and invaluable doctrine, which is worthy to be recorded and remember’d in all Succeeding ages. “We hold these truths to be Self evident, that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happyness.”

Here Sir, was a time in which your tender feelings for your selves had engaged you thus to declare, you were then impressed with proper ideas of the great valuation of liberty, and the free possession of those blessings to which you were entitled by nature; but Sir how pitiable is it to reflect, that altho you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of mankind, and of his equal and impartial distribution of those rights and privileges which he had conferred upon them, that you should at the Same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the Same time be found guilty of that most criminal act, which you professedly detested in others, with respect to yourselves.

Sir, I suppose that your knowledge of the situation of my brethren is too extensive to need a recital here; neither shall I presume to prescribe methods by which they may be relieved; otherwise than by recommending to you and all others, to wean yourselves from these narrow prejudices which you have imbibed with respect to them, and as Job proposed to his friends “Put your Souls in their Souls stead,” thus shall your hearts be enlarged with kindness and benevolence toward them, and thus shall you need neither the direction of myself or others in what manner to proceed herein.

The entire text of Banneker’s letter can be read here.

Stop 19: Footnotes

[1] Residence Act, 1 Stat. 130 (1790).

[2] District of Columbia Organic Act, 2 Stat. 103 (1801).

[3] “Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia,” Boundary Stones, accessed December 19, 2021.

[4] Boundary Markers of the Nation's Capital: A Proposal for their Preservation & Protection (unpublished report, National Capital Planning Commission, Washington, D.C. 1976), 8.

[5] Benjamin Banneker, Benjamin Banneker’s Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris, for the Year of our Lord, 1792, William Goddard and James Angell, Baltimore, 1792.

[6] “To Thomas Jefferson from Benjamin Banneker,” August 19, 1791, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed December 30, 2021.

[7] Alexandria Black History Museum, “A Free Man Defies all Boundaries,” exhibit panel from Securing the Blessings of Liberty: Freedoms Taken and Liberties Lost, 2006.

To Return to Waterfront Park

To return to Waterfront Park and the starting point of this trail, continue around Jones Point, walk under the Wilson Bridge, and follow the river north approximately 1.2 miles to the foot of King Street.

Alternatively, consider visiting the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery and Memorial, located about 3/4 of a mile away at 1001 South Washington Street. To get there, retrace your steps to the Wilson Bridge and turn left at the Mt. Vernon Trail. Stay on the south side of the bridge and follow the Mount Vernon Trail as it climbs to South Washington Street/The George Washington Memorial Parkway. Cross at this intersection and turn right to cross over the beltway. The cemetery will be on the left.

Conclusion

The stories we have to tell about African American history are innumerable and span from the river’s edge to the west side of the city.

For more information on the history of Alexandria’s African American community, visit:

- The Alexandria Black History Museum

- The Alexandria Archaeology Museum

- The Freedom House Museum

- Alexandria African American Heritage Park

- Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial

- Fort Ward Museum and Historic Site

- The Charles Houston Recreation Center

For additional information on the history presented in this tour, please visit this website.