Archaeology FAQ

What is archaeology?

Archaeology is a science. Archaeologists study human culture by looking at physical evidence that was left behind by people. They follow scientific procedures and use scientific tools to understand this evidence. In Alexandria, archaeologists study people that lived in the area from over 10,000 years ago until today.

Archaeologists ask questions, research, and use evidence like artifacts and features to answer their questions. That evidence is then brought back to a lab where it is studied and preserved.

Archaeologists study:

- artifacts, small objects like buttons from clothes, seeds from meals, or pots for cooking. They even examine very small evidence like pollen from crops they grew or parasites that lived in their digestive system.

- large features like building foundations, roads, or drinking wells.

changes that people made to the environment.

Archaeological Process

Step 1: Ask a Question

Archaeologists always start work by asking questions about people in the past. They then make a plan to answer those questions by using physical evidence like artifacts and features. Often these questions come from researching a particular place or time period and wanting to learn more about the people that lived in that place and time.

An archaeologist could ask:

- What did people used to eat a long time ago?

- What was this building used for? Was it always used for the same purpose, or did it change over time?

- Where were people living 5,000 years ago? Did they stay in one place all year, or did they move from one area to another?

- How did people decorate their homes? Where did those items come from?

Step 2: Research

Historical archaeologists study places and time periods that have a written record. They research the past by finding original written records from the period of time that they are studying. These types of records are called primary sources. An Alexandria newspaper from 1784, a photograph of an Alexandria street from the Civil War, maps of the town, or a diary from a person who lived here are great examples of primary sources.

Secondary sources, such as history books, are written about the past by people that were not around to experience it for themselves. They can still be useful if they are true. Stories, or rumors that are loosely based on fact, are passed from generation to generation and can be written down as fact later on. It is important for archaeologists and historians to distinguish between fact, opinion and legend.

Step 3: Finding and Registering a Site

Often archaeologists locate a site not to dig, but to know if an area needs protecting. Archaeological sites can be located in many ways. The most common in Alexandria are field survey and research.

Field Survey

Archaeologists walk in straight lines across the ground looking for artifacts. Sometimes they dig small "shovel test" holes and then screen the soil to look for any artifacts.

Sometimes archaeologists don't have to dig into soil or go underwater to look for evidence. Instead, they use remote sensing equipment like aerial photography, or noninvasive survey like ground penetrating radar (GPR), magnetometry, soil resistivity, light detection and ranging (LiDAR), and sound navigation and ranging (SONAR).

- What tools are used? Shovel, screen, compass, measuring tape, GPR, LiDAR, SONAR, aerial photography, and survey equipment like total stations.

- What challenges do they face?

- Field work is outdoors. Bad weather, poisonous plants, and pests like ticks can make work difficult or dangerous.

- Archaeologists follow a grid system of straight lines to know exactly where they are working. Following this grid can be tricky when working outdoors, especially when there are trees and other obstacles in the way! Trees and other vegetation can also make it hard to see and difficult to do remote sensing like aerial photography.

- Digging shovel tests in the ground is hard work and takes a long time.

- Some sites are far away from any roads, electricity, bathrooms, or cell phone signal.

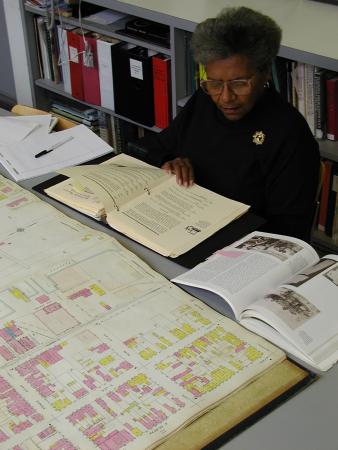

Historical research: Documents and Records

Maps, deeds, and census records show where buildings were built and where people lived and worked. Historical archaeologists and researchers work together to gather and sort information.

- What tools are used? Geographic Information Systems (GIS) maps, computer databases, and library archives.

- What challenges do they face? Records and other information are kept in many different places and they can be hard to track down.

registering a site

Once found, a site is registered and is given its own name and number. Archaeologists then make a base map that shows where the site is located. During excavation, archaeologists add to the map to show which portions of the site were excavated and where features and artifacts were discovered. A datum point, or point of reference from a United States Geological Survey benchmark, is established, and measurements are taken from that point to know exactly where artifacts or features are found.

Step 4: Excavating the Site

Once archaeologists excavate an archaeological site, it is destroyed. Today, archaeologists excavate a site only if it is already in danger of being disturbed, or if there is an important research question that cannot be answered in any other way.

Archaeologists carefully excavate, or dig through the soil, to uncover artifacts and features. They use trowels to remove soil and then sift it through a screen to make sure that no artifacts are lost. The artifacts are placed in separate labeled bags to send back to the lab for processing.

Archaeologists work on a grid system which gives every place a specific coordinate, or address, on the grid. Most archaeologists work in excavation units, or squares. Excavation take a long time. Sometimes, only a few test squares within the site grid will be dug, while on other sites the entire area is excavated.

Archaeologists excavate down into the ground looking for changes in the color and texture of the soil. These vertical soil layers make up the stratigraphy of the archaeological site. These stratified layers can show where people or the environment have changed the area due to things like erosion, gardening or farming, littering or dumping trash, or constructing buildings. Each layer represents a segment of time, much like a timeline. Each layer is excavated separately and is recorded and mapped before moving on to the next layer.

Archaeologists document everything they see, including changes in soil color and texture, by taking notes and making maps. A Munsell Color Chart provides standard names for soil colors.

The most important information that they document is each artifact's exact location on a site. This is known as its context. Context is the story that surrounds the artifact. It includes the location of other artifacts and information found with it. Archaeologists study artifacts found in the same context to better understand what happened in that exact spot a long time ago.

Artifacts from each context are placed in a bag marked with the grid coordinates and the layer number. This exact location where the artifacts are found – the square, layer and feature – is called the provenience, or context. Each provenience is assigned a unique record number, to help keep track of the artifacts.

- What tools are used?

- To dig: Shovel, screen, trowel, bucket, dustpan, and sometimes heavy equipment like backhoes or excavators

- To document: string and line levels, plumb bob, measuring tape, field records forms to write notes and draw maps, soil color charts (Munsell), and paper artifact bags

- To stay safe: tents, water, hard hats, boots, and safety vests

- What challenges do they face?

- Field work is outdoors. Bad weather, poisonous plants, and pests like ticks can make work difficult or dangerous.

- Archaeologists excavate on a grid system. Finding exact coordinates in an open field or measuring out a square unit can be difficult. Small errors in measurement over time can be magnified over time as new units are measured off of older units.

- Excavation is hard work, especially in rocky or compact soil, or in soil that is hard to pass through a metal screen.

- Excavation can be dangerous. Archaeologists sometimes work in contaminated soils or deep enough into the ground that they need to shore up the soil to prevent it from collapsing on top of them.

- Archaeologists have to make careful observations about soil color and texture. This can be difficult for people who are visually impaired.

- Sometimes the ground has already been disturbed by construction or deep plowing. This means the context of the artifacts has been lost.

Step 5: Cleaning and Cataloguing Artifacts

Excavation is only a small part of an archaeologist's work. After excavation, the job of cleaning, analyzing and interpreting begins. For every hour of excavation it takes at least twenty hours of laboratory and other work to complete an analysis and report. Often this study and analysis continues for years after the excavation has been completed.

Cleaning Artifacts: Artifacts arrive in the Alexandria Archaeology Laboratory from the sites in bags and boxes labeled according to the provenience, the specific location where an artifact or feature is found in the ground. Most artifacts are washed using water and a toothbrush. Some artifacts, like iron or organic materials like leather, can be damaged by water and are dry cleaned.

Sorting and Labeling Artifacts: When dry, the artifacts are sorted within each provenience into categories such as ceramics, glass, structural material (window glass, nails), miscellaneous (buttons, pipes, toys), organic artifacts (cloth and leather), bone, shell and seeds. Some artifacts are labeled with their provenience using a removable glue. Artifact assemblages (all artifacts from the same context) are studied together, making it necessary to mark or label each artifact.

Cataloguing: Cataloguing is the most difficult part of laboratory work. Alexandria Archaeology uses an illustrated glossary put together for in-house use, study collections, an extensive library of books, and the internet for aid in artifact identification. The staff and volunteers refer to a notebook of standardized terms to be used in cataloguing artifacts, to provide consistency and accuracy. Each artifact or each group of artifacts with the same description (e.g., five sherds of plain creamware body sherds; two bone 4-hole buttons with the same measurements; 50 fragments of window lass) are assigned a catalogue number, and described on a catalogue sheet. The information is entered into a computer database, along with digital images of the artifacts. The database can then be used to manipulate the artifact catalogue to analyze the site.

- What tools do they use?

- Cleaning: toothbrushes, sieves/colanders, sink, drying racks

- Sorting and labeling: magnets for testing for iron, printed paper labels, B-72 adhesive and paintbrushes

- Cataloguing: weighing scale, primary research materials like historical catalogs, secondary research materials like lab manuals, physical comparative collection, computer database system, camera

- What challenges do they face?

- Sometimes artifacts are processed in the lab long after they were excavated. In some cases, the original field records and notes aren't clear, which makes it more difficult to understand the collection.

- Some artifacts are difficult to identify. Archaeologists in the lab use books, lab manuals, and comparative collections to help identify unknown artifacts. Sometimes they need to reach out to other experts in the field to find a match.

- Washing and labeling artifacts can be time consuming. Gluing a small label onto a small artifact can be tricky without covering up identifiable parts of the artifact.

- Some materials are easier to preserve than others. Inorganic materials like ceramic and glass are very stable. Organic materials like wood, bone, shell, leather, and cloth are more susceptible to breaking down over time. They often need additional care or more regular maintenance.

Other Lab Processes:

- Crossmending Ceramics and Glass - Crossmending is the process of piecing sherds together to form a vessel, regardless of where the artifact fragments were found on the site. They are held together temporarily with tape to reveal the shape and size. Artifacts are only restored with reversible glue if they are to be exhibited, as restored vessels require more storage space and are subject to breakage. This process is like doing many three-dimensional jigsaw puzzles at the same time.

- Faunal Analysis: Faunal analysis, the study of animal bones, is also an important area of study in the lab. Faunal studies can tell us about the diets, types of livestock, socioeconomic status of the people, butchering practices, foodways, as well as the economy of the period. Faunal analysis requires a lot of specialized knowledge, and is normally done by consultants.

- Relative Dating: One aspect of interpretation is to determine the period or periods of time that the site was occupied. Artifact groups from each provenience are studied as a unit. These artifacts provide the archaeologist with a point to begin their study of the site. Manufactured products are very useful because their date and place of manufacture can often be identified according to advances in technology and changes in stylistic preferences. Archaeologists must then estimate when the artifacts were discarded. This can be a specific point in time or a span of many years, decades or even centuries. The concept of terminus post quem, Latin for 'the date after which', is used to determine the date of deposition, such as when a layer of trash was dumped into a pit or abandoned well. All of the artifacts found together in one level had to have been put there after the date that the newest artifact was manufactured. The date when this most recent artifact was first manufactured is known as the terminus post quem. A good example of this process can be found in Hayti: A 19th-Century Free African American Neighborhood.

- Absolute Dating: Absolute dating techniques using scientific methods, such as Radiocarbon (Carbon 14) or Potassium-Argon, are expensive, are only used on organic materials, and have a margin of error that can be as much as plus or minus 250 - 500 years. Because manufacturing information and dated samples of artifacts are available for the historic period, these absolute dating techniques are not necessary on most Alexandria sites.

What happens to archaeological materials once they’ve been excavated?

Go behind the scenes with archaeologist and collections manager Tatiana Niculescu to look at the City’s efforts to preserve, research, and exhibit artifacts both big and small.

Step 6: Curating the Collection

All artifacts are stored together, along with their field and lab records, in a temperature and humidity controlled environment. When archaeologists or other researchers have new questions, they can go back to the collection and study them further.

Some artifacts require extra stabilization to remain preserved over time. Depending on the material type and condition of the artifact, this can involve chemical treatments, mechanical cleaning, or simply storage in a specific environment.

The Alexandria Archaeology Museum stores collections and related field records, catalogues and other supporting documentation from most excavations within the city limits – whether the sites were excavated by staff or by archaeological resource management firms. The artifacts are stored in appropriate bags, boxes and other storage materials, and in a storage facility with a stabile climate, in order to ensure their long-term preservation. A database helps track the location of the artifacts, as well as their catalogue descriptions.

- What challenges do they face?

- Once artifacts are processed, they must be cared for. Maintaining and having enough physical space for collections is often a problem.

- As technology changes, more digital space is necessary for storage, and older formats of files must be updated. There must be enough digital space for the digitized notes, maps, artifact catalog, and field and lab photos.

- Managers of collections cannot monitor the space 24 hours a day. If the power goes out, a pipe bursts, or the temperature or humidity of the space changes, that can damage the collection.

Step 7: Sharing Results

The interpretation of the data gathered from the excavation is an ongoing and lengthy process, but cannot be overlooked. There is no point to digging and analyzing the artifacts unless you are prepared to find out what all of the information means. Ultimately, interpretation takes the form of publications such as site reports and books, lectures and public events, and museum exhibitions and school programs.

For archaeologists in Alexandria, the interpretation of each site adds to our knowledge of the growth and development of the City. It also provides a clearer understanding of how we arrived at our current state and the possibilities for our future.

Site reports, journal articles, book chapters, theses and papers on archaeology in Alexandria are listed in an online Alexandria Archaeology Bibliography and on the interactive Alexandria Archaeology Report Finder map.