Alexandria Canal FAQ

What is a canal?

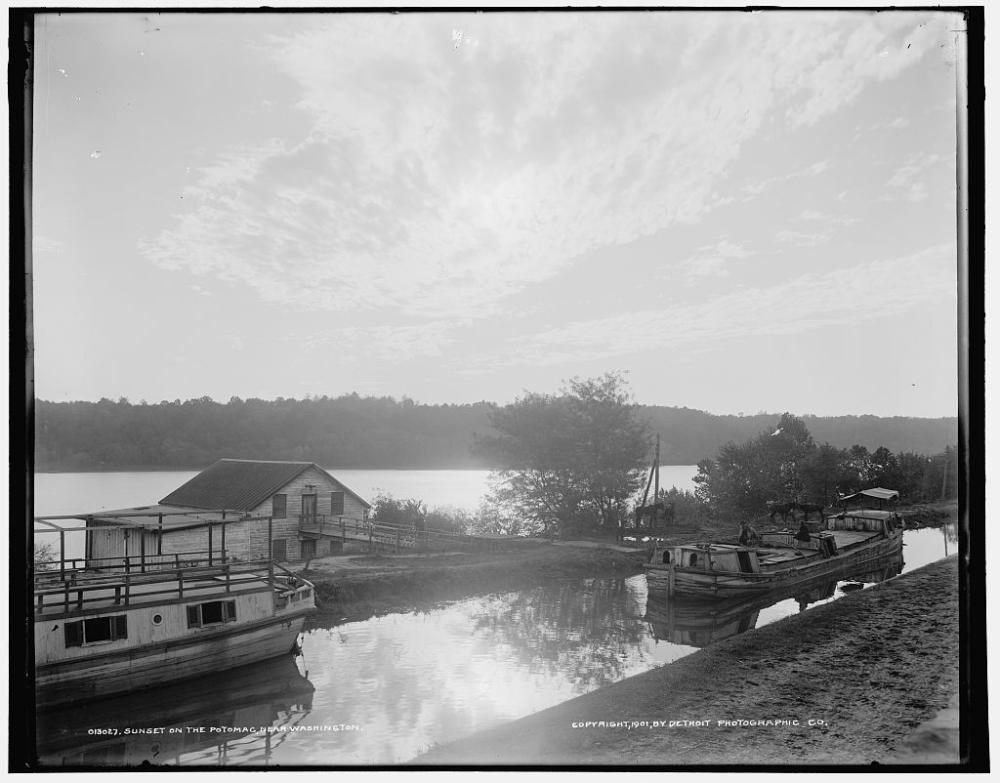

A canal is a manmade waterway. People built canals to transport goods and resources because it was easier to float them over water than to pull them over land by horse and wagon. Unpowered canal boats were often pulled by mules or horses walking a parallel towpath. Boats and barges were sometimes powered by steam as well. Locks and aqueducts allowed the boats to follow a more direct route, change elevation along the way, and travel the canal in both directions.

Lock: A lock is a small section of a canal that raises or lowers the water level, much like an elevator, allowing boats to navigate changes in elevation, including traveling uphill.

Basins/Pool: Wider sections of the canal are known as pools or basins. Basins served as storage reservoirs for canals, providing water for the locks. They also provided space for boats to load, unload, change direction, and wait for passage through a lock.

Aqueduct: Canal aqueducts are bridges for boats. They allow canal barges to cross both deep and swift river channels.

Why was the Alexandria Canal built?

In the late 18th and early 19th century, canals increased access to inland trade and connection to the growing western frontier. Unlike roads, they were an efficient way to move large amounts of goods across great distances. Railroads eventually won the 19th century transportation war as a cheaper and faster means of transport.

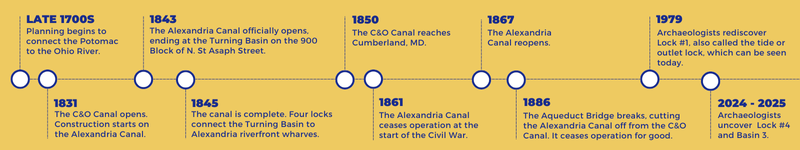

Initial plans for the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal (C&O) promised a route between the Potomac River and the Ohio River in Pittsburgh. Construction began in 1828, but the finished canal only made it as far west as Cumberland, MD and terminated at nearby Georgetown, cutting out Alexandria and threatening its position as a key player in the river trade.

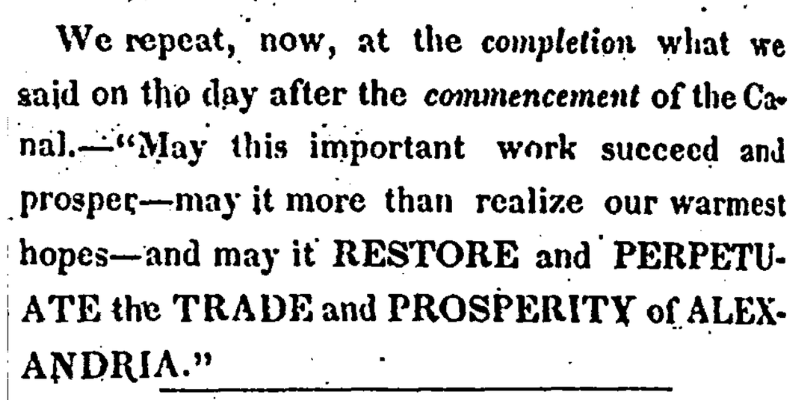

The town sought economic advantage by building the Alexandria Canal as a connecting spur to the C&O to reclaim their position as an economic power in the region. Competition was tight, but unlike neighboring Georgetown, Alexandria had the benefit of a deep-water port for merchant ships and locks that allowed the canal boats to reach the wharves along the Potomac.

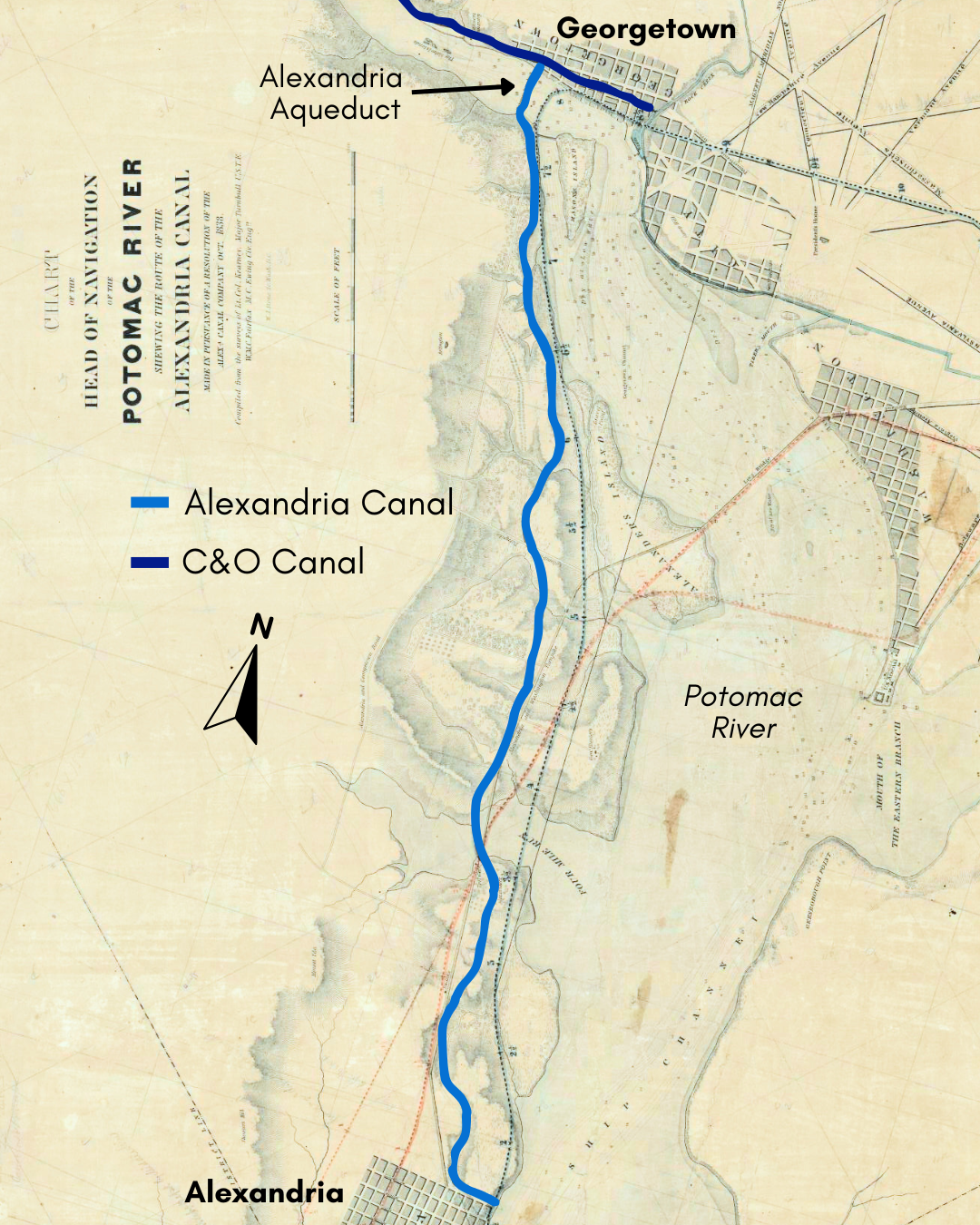

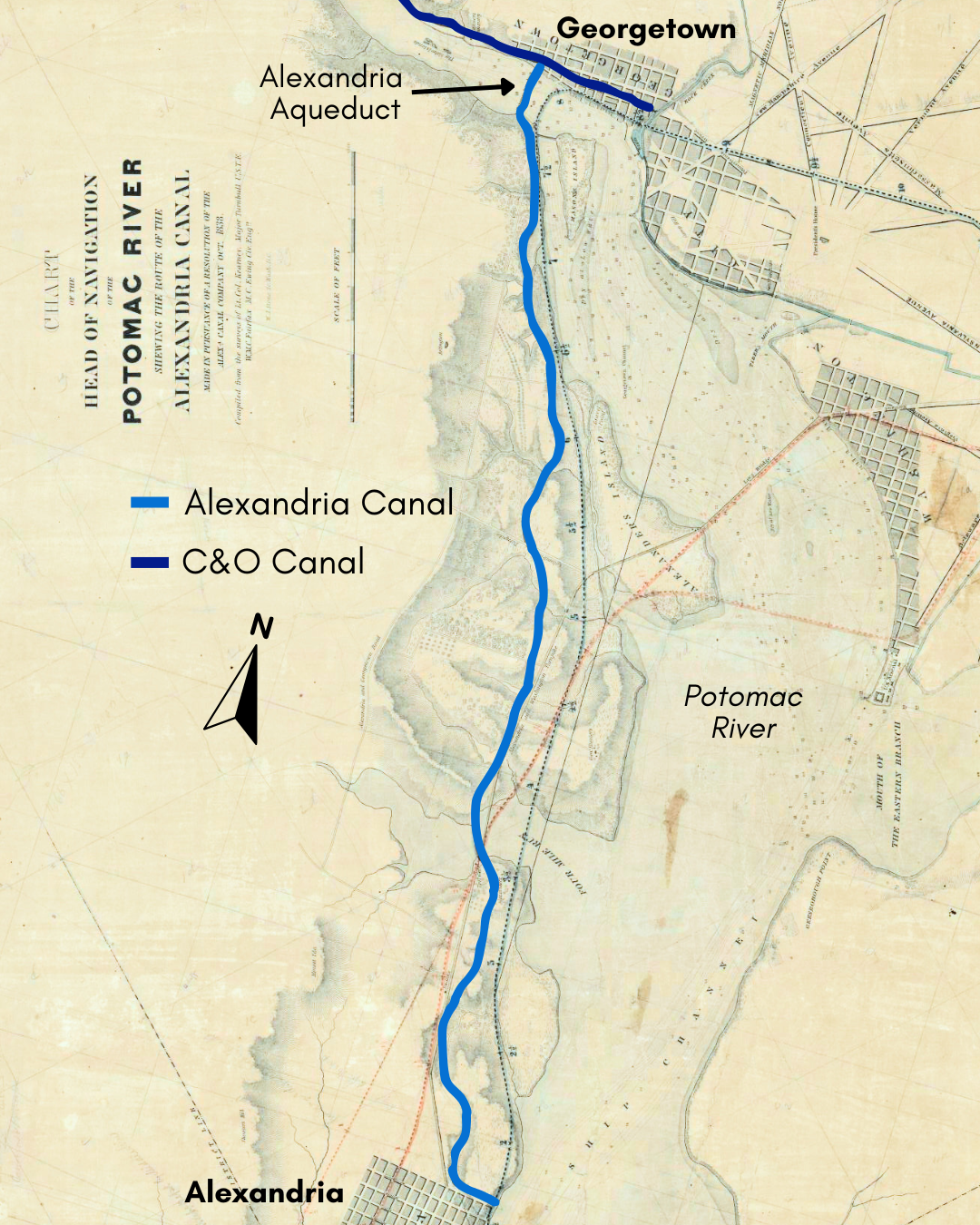

Chart of the head of navigation of the Potomac River shewing the route of the Alexandria Canal: made in pursuance of a resolution of the Alex'a Canal Company Oct. 1838. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

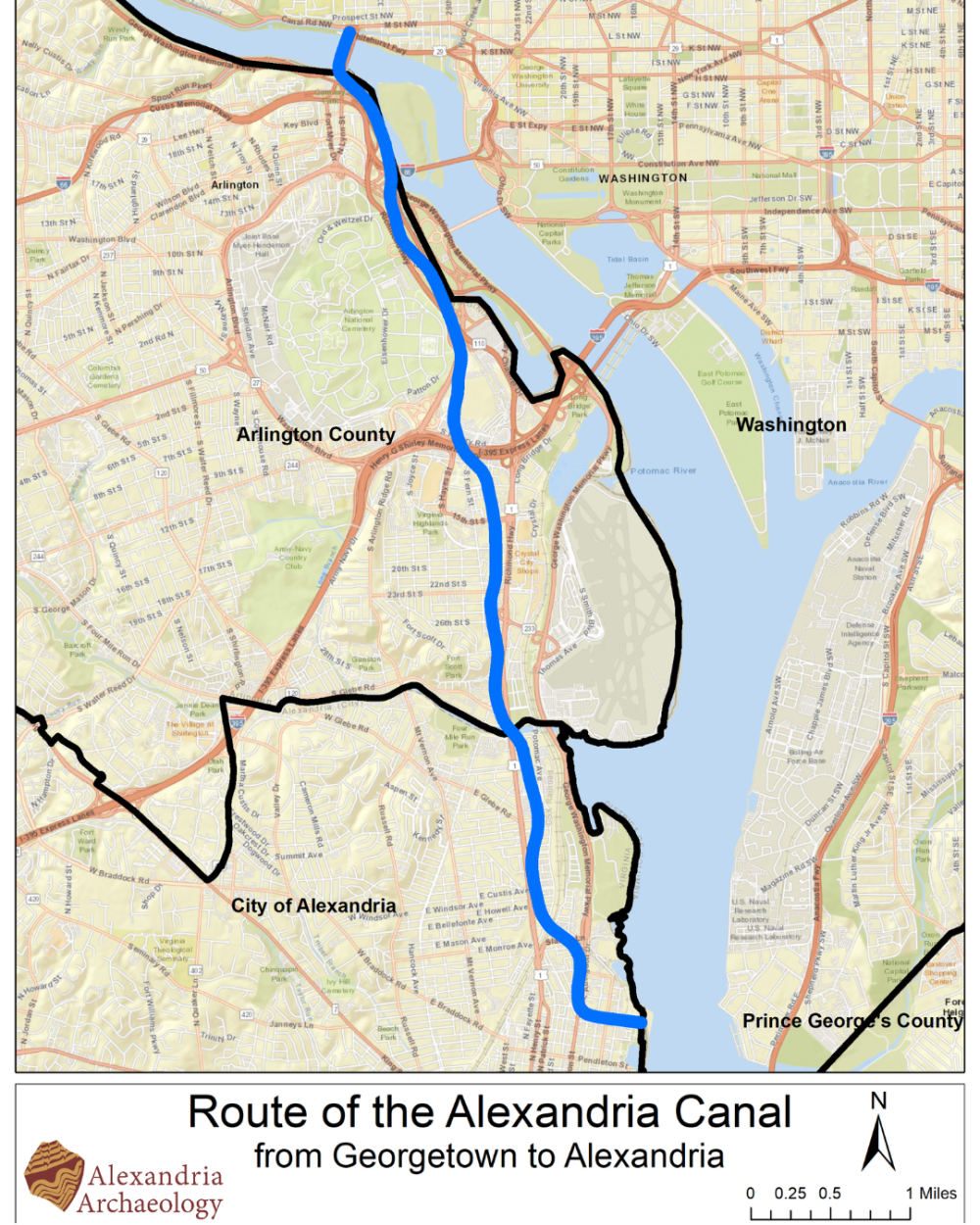

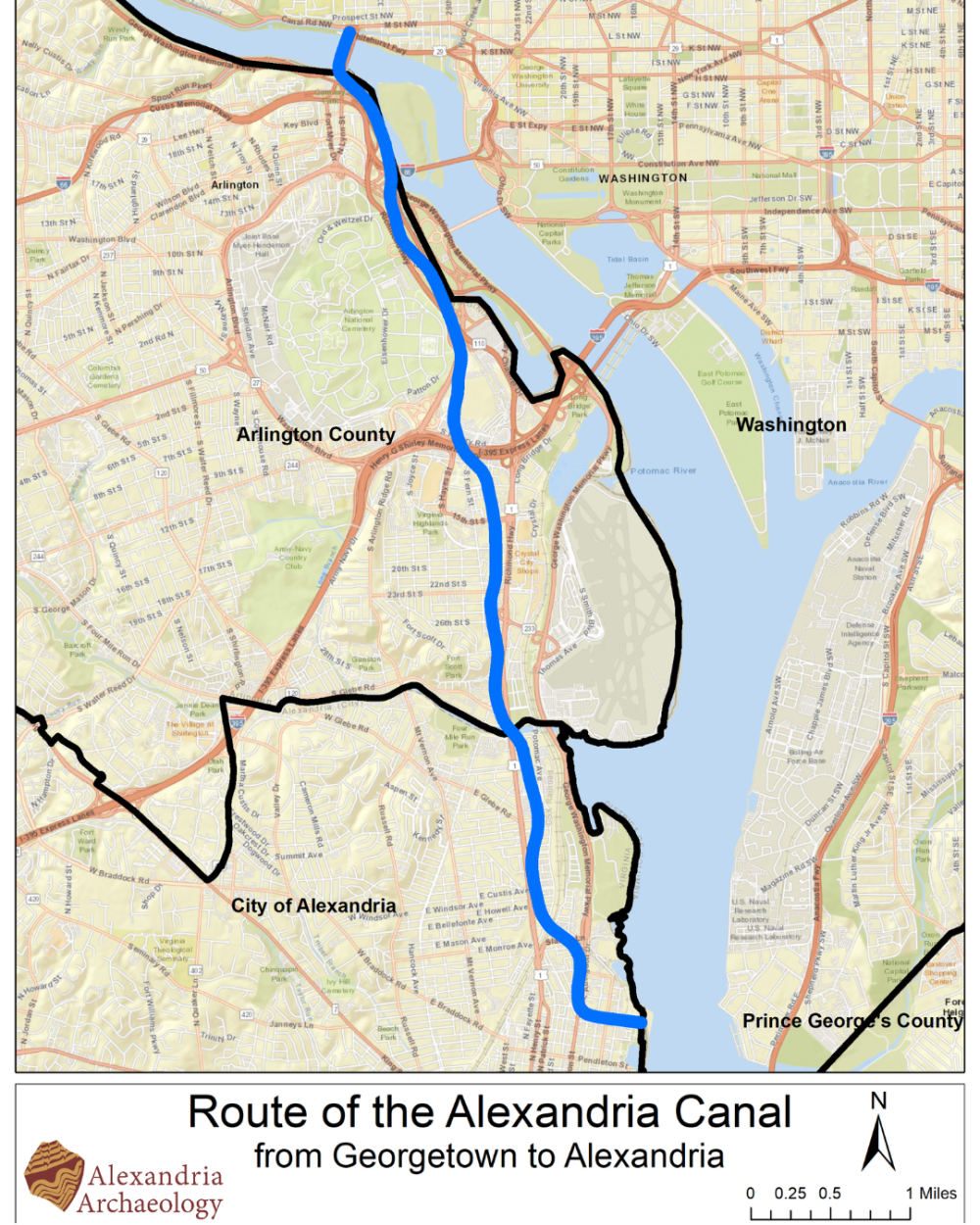

What path did it take?

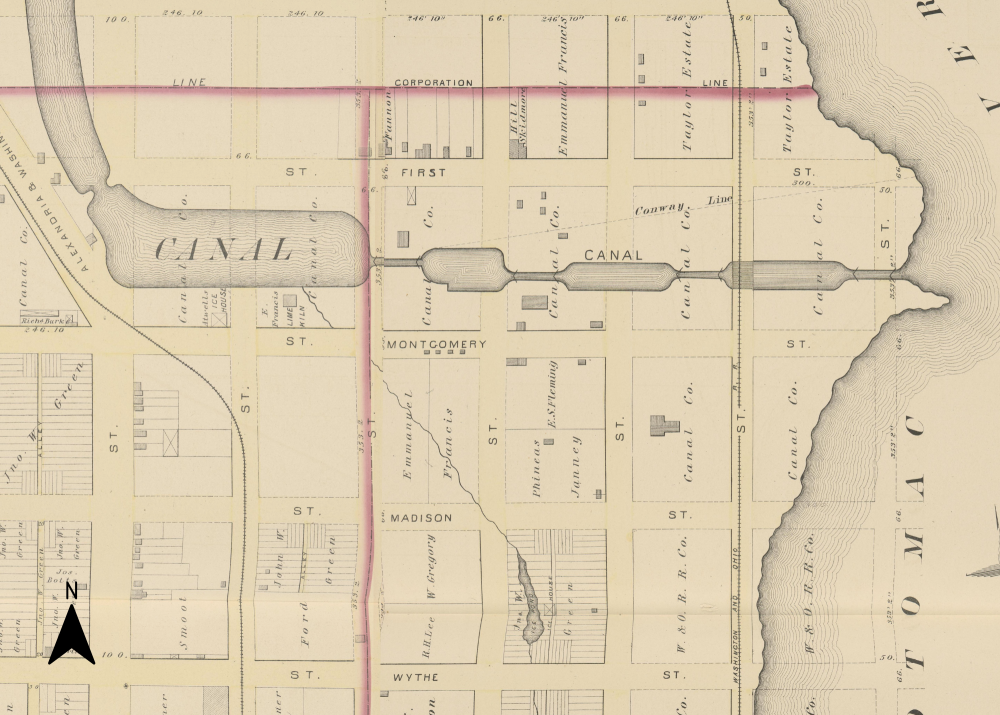

Once complete, the Alexandria Canal was seven miles long. Starting at today’s Tide Lock Park, the canal ran west between Montgomery and First Streets until it reached the Turning Basin near today's Washington Street. There, the canal made its way north towards Georgetown, briefly following today's George Washington Memorial Parkway before veering a bit west to follow a similar path as today's Route 1. The final stretch brought it across the Potomac River on the Aqueduct Bridge to meet with the C&O Canal in Georgetown. Boats would travel the canal in both directions.

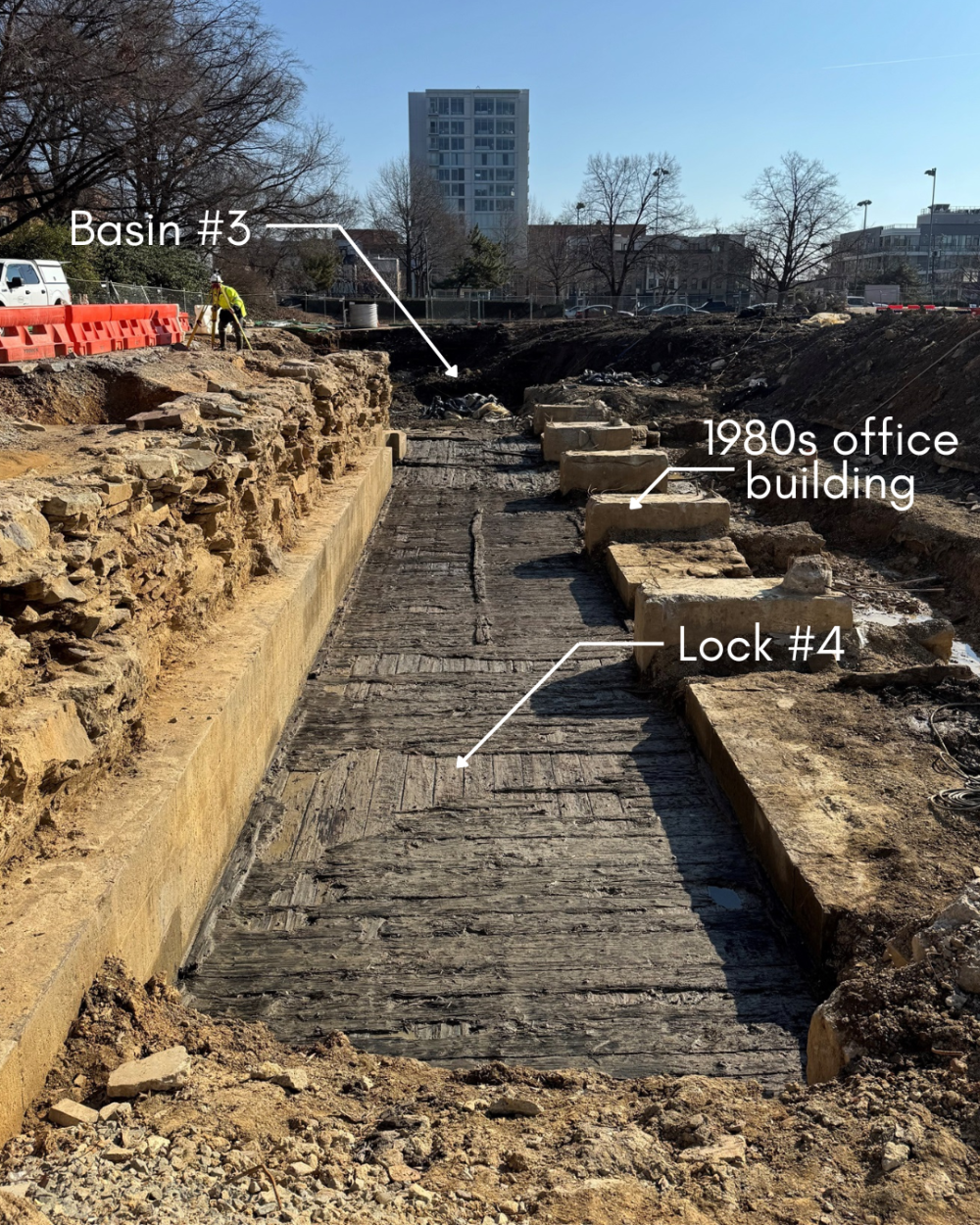

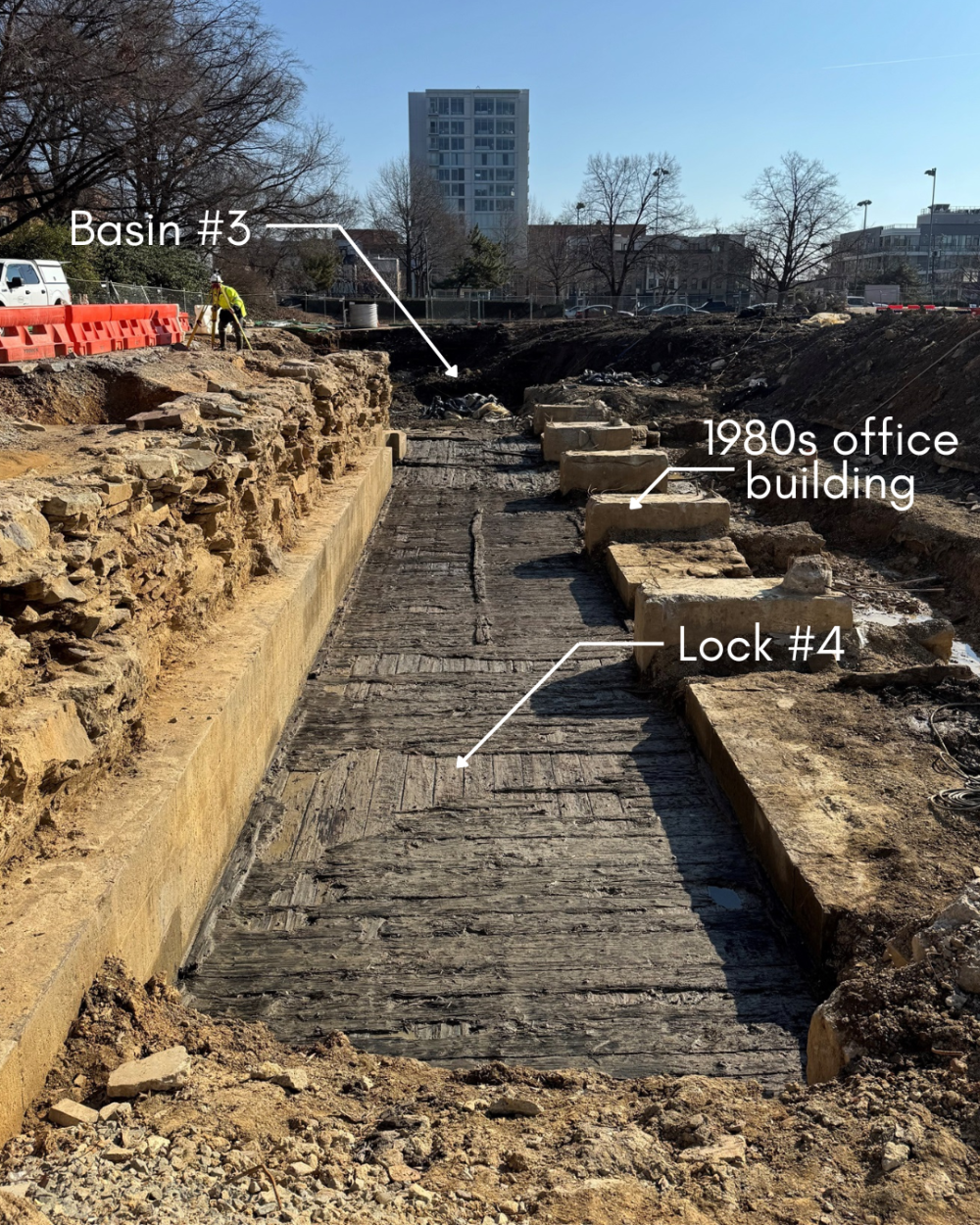

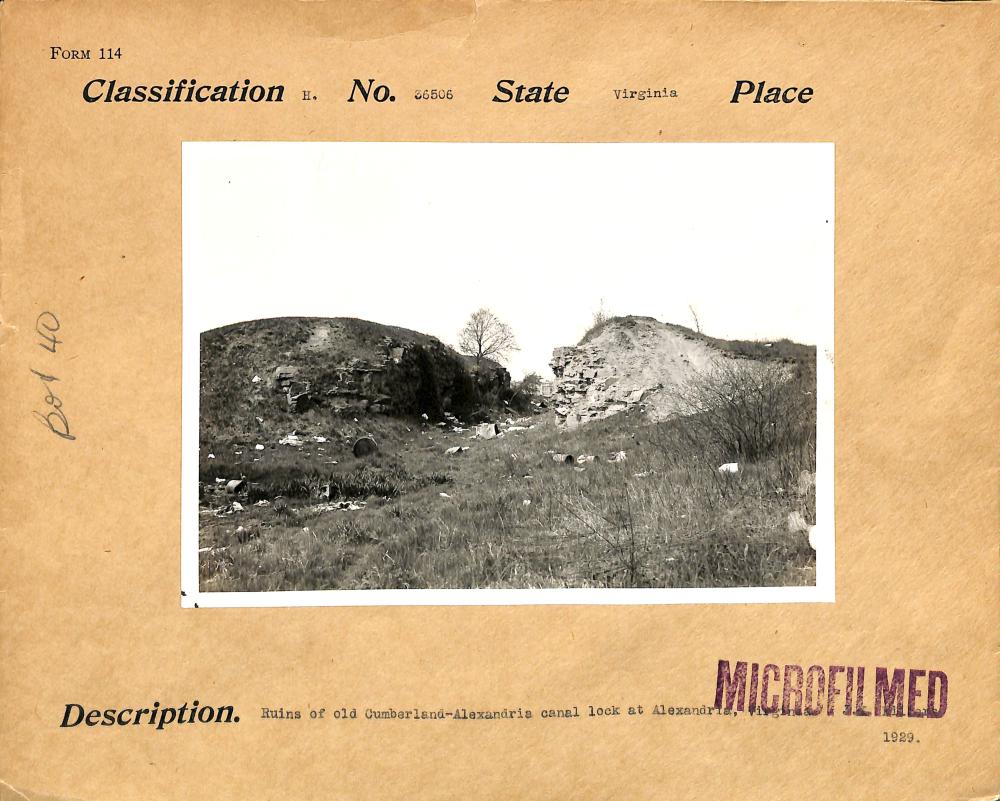

The Alexandria Canal had four locks to manage the 38-foot elevation change between the city’s Potomac River waterfront and the turning basin near Washington and First Street. The 2024-2025 excavation uncovered the westernmost lock at the 900 block of North Pitt Street. In 1979, archaeologists rediscovered the easternmost lock, known as Lift Lock No. 1 or the Tidal Lock, now reconstructed at Tide Lock Park.

The Alexandria Canal had four basins within city limits. In 2017, archaeologists working at 901 North St. Asaph Street uncovered the remains of the Turning Basin, a wide and shallow pool that allowed canal boats and barges to change direction, load and unload cargo, and wait for passage through the locks. The 2024-2025 excavation at 900 North Pitt Street uncovered a portion of the third basin, directly to the east of the larger turning basin.

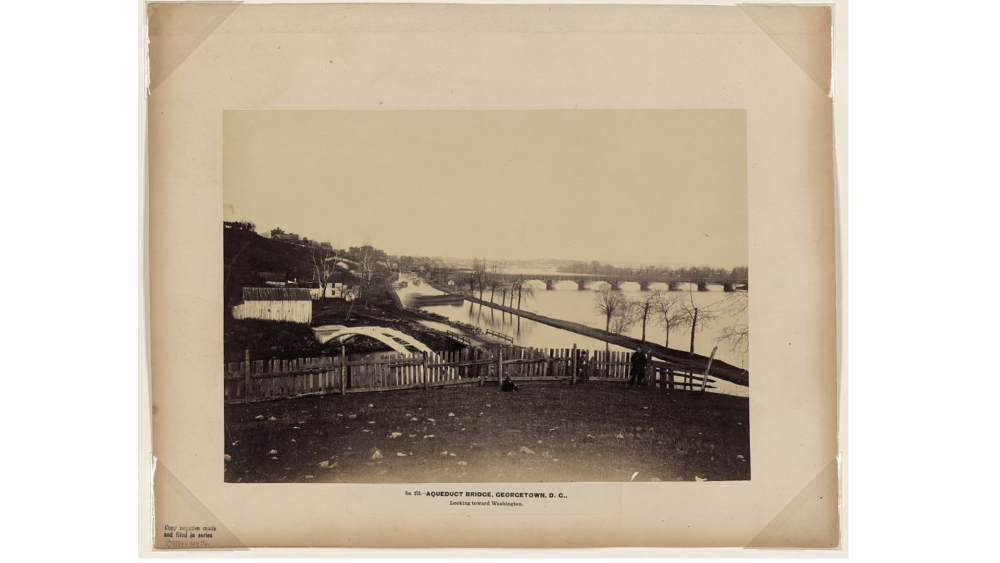

The Aqueduct Bridge, also known as the Alexandria Aqueduct, connected the Alexandria Canal on the western shore of the Potomac to the C&O Canal in Georgetown, crossing above the Potomac River near where the Key Bridge is today. The over 1000-foot span allowed boats to maintain their elevation, rather than descending to the river and then ascending again to the level of the C&O Canal, and allowed the unpowered canal boats to cross the deep and swift river channel. The Alexandria Aqueduct was completed in 1843 and removed in 1923, leaving behind the the remains of the north abutment on the Georgetown side of the Potomac River.

How was it built?

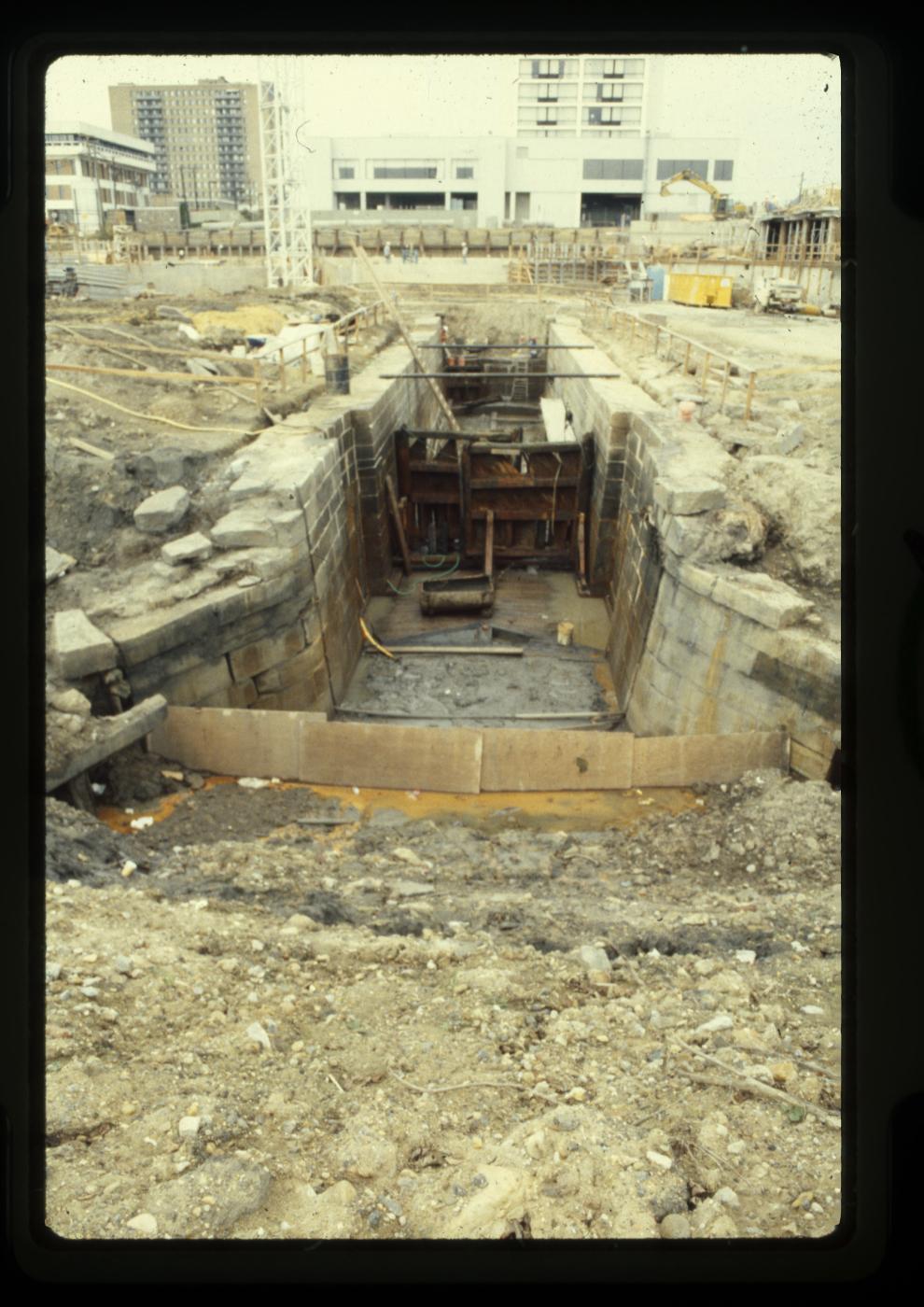

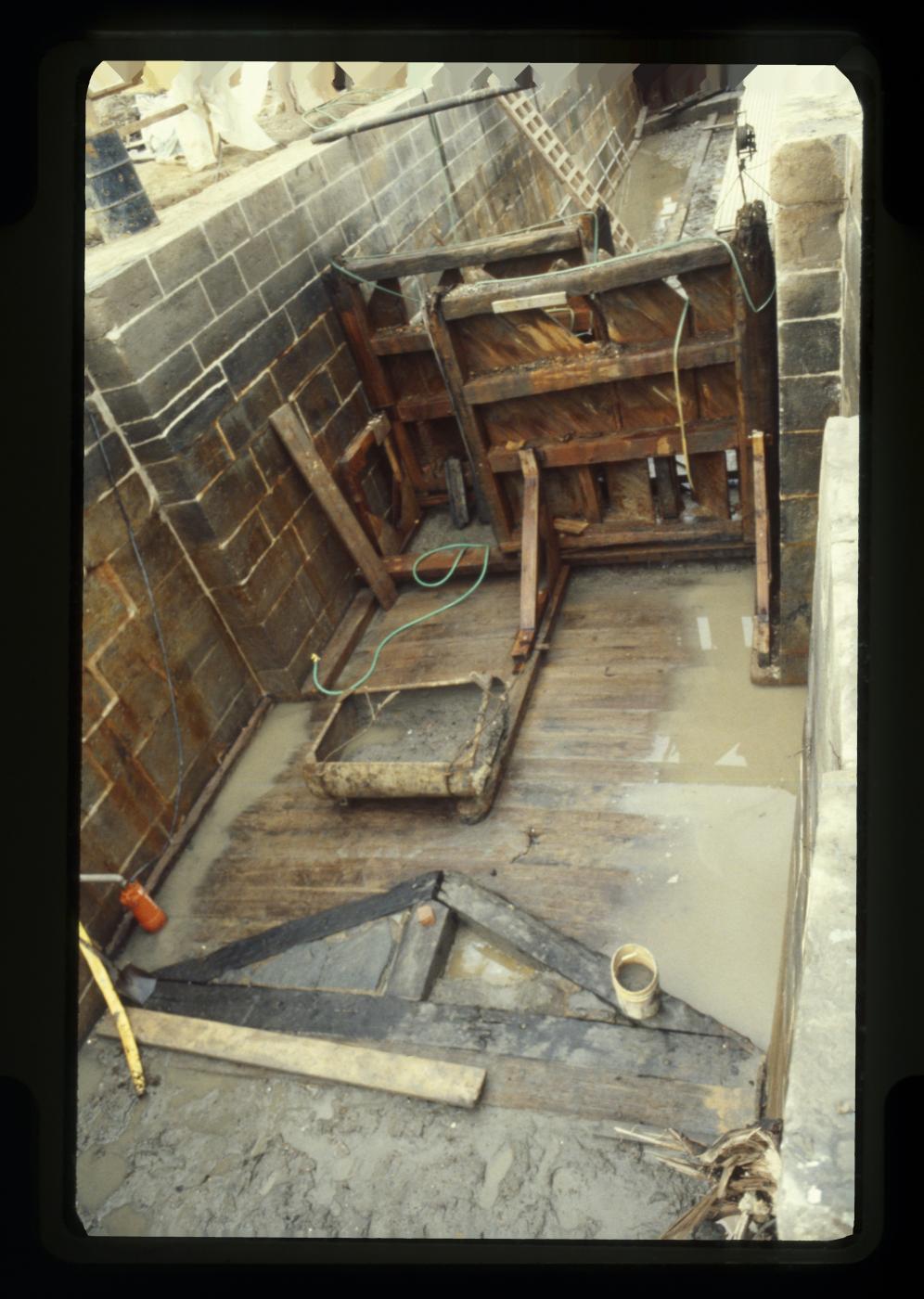

The Alexandria Canal was built largely through the forced labor of enslaved people, as well as paid labor. The majority of the canal was a clay-lined ditch, called a prism, with a towpath on one side for draft animals to pull the boats and barges. The locks were built out of timber, cement and locally available Aquia sandstone. Archaeologists have uncovered portions of the canal and have documented the wood floors, stone walls, and remnants of the lock gates and mitre sills.

When was the Alexandria Canal in use?

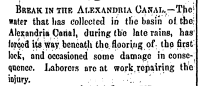

The construction of the Alexandria Canal began in 1831, the year that the Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) Canal opened. It opened for traffic in Alexandria in 1843 and was completed down to the Potomac River by 1845. The Canal required the aqueduct bridge and the C&O Canal to be in service and all were expensive and difficult to maintain. The Alexandria Canal was out of commission during the Civil War, reopened in 1867, and then ceased operation in 1886 when the Aqueduct Bridge was damaged. By the early 1900s many usable finished or dressed stones from the lock walls had been repurposed and Alexandrians began dumping trash and fill into the former canal.

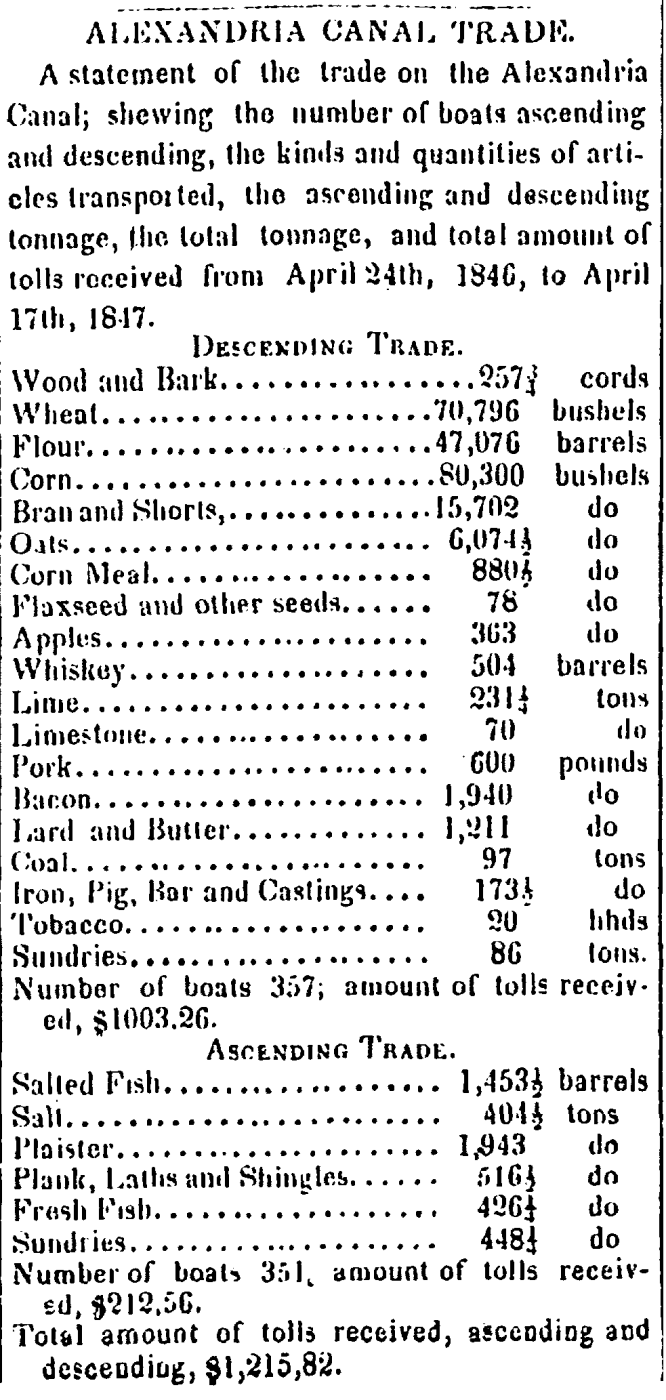

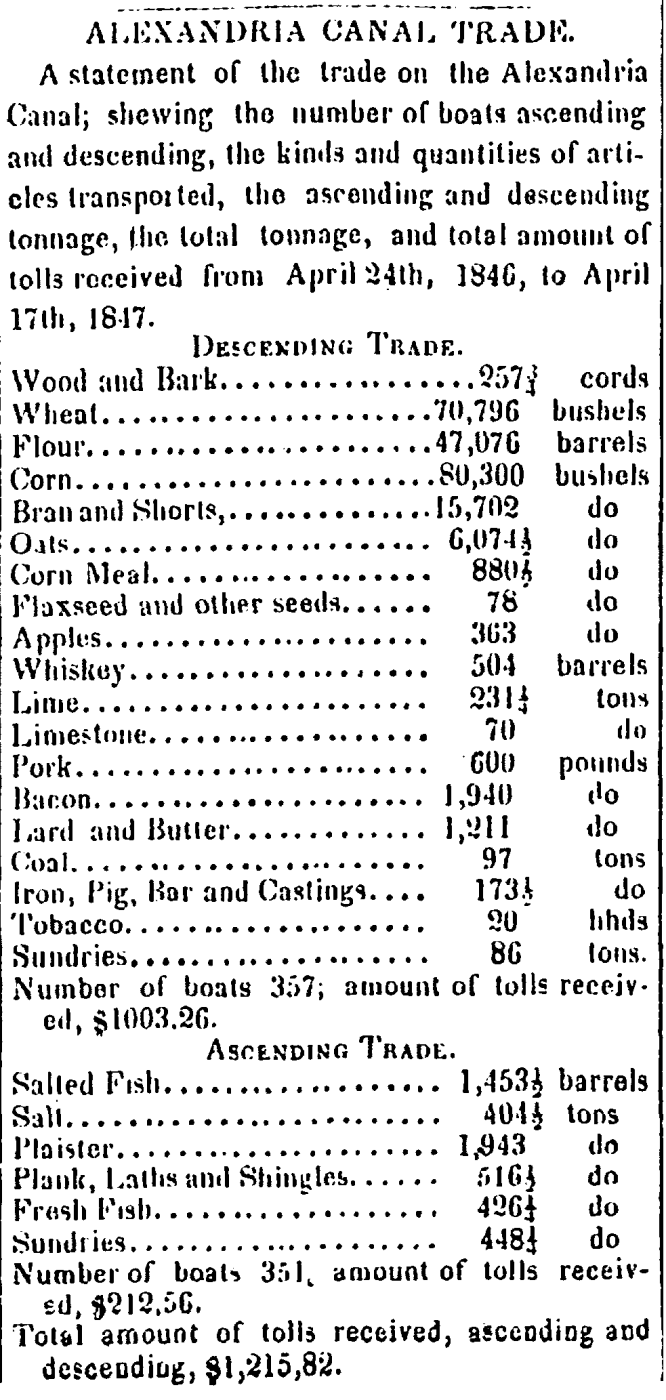

What did the boats carry?

The Alexandria Canal was used mainly for commerce, but was also open for passenger travel. Grain dominated the eastern-bound trade prior to 1850, before being surpassed by coal. Raw goods like stone and timber were also shipped. Some goods stopped in Alexandria, but most were bound for other destinations. Western-bound trade included fish, salt, building materials, guano, and consumer goods.

Can I still see the canal?

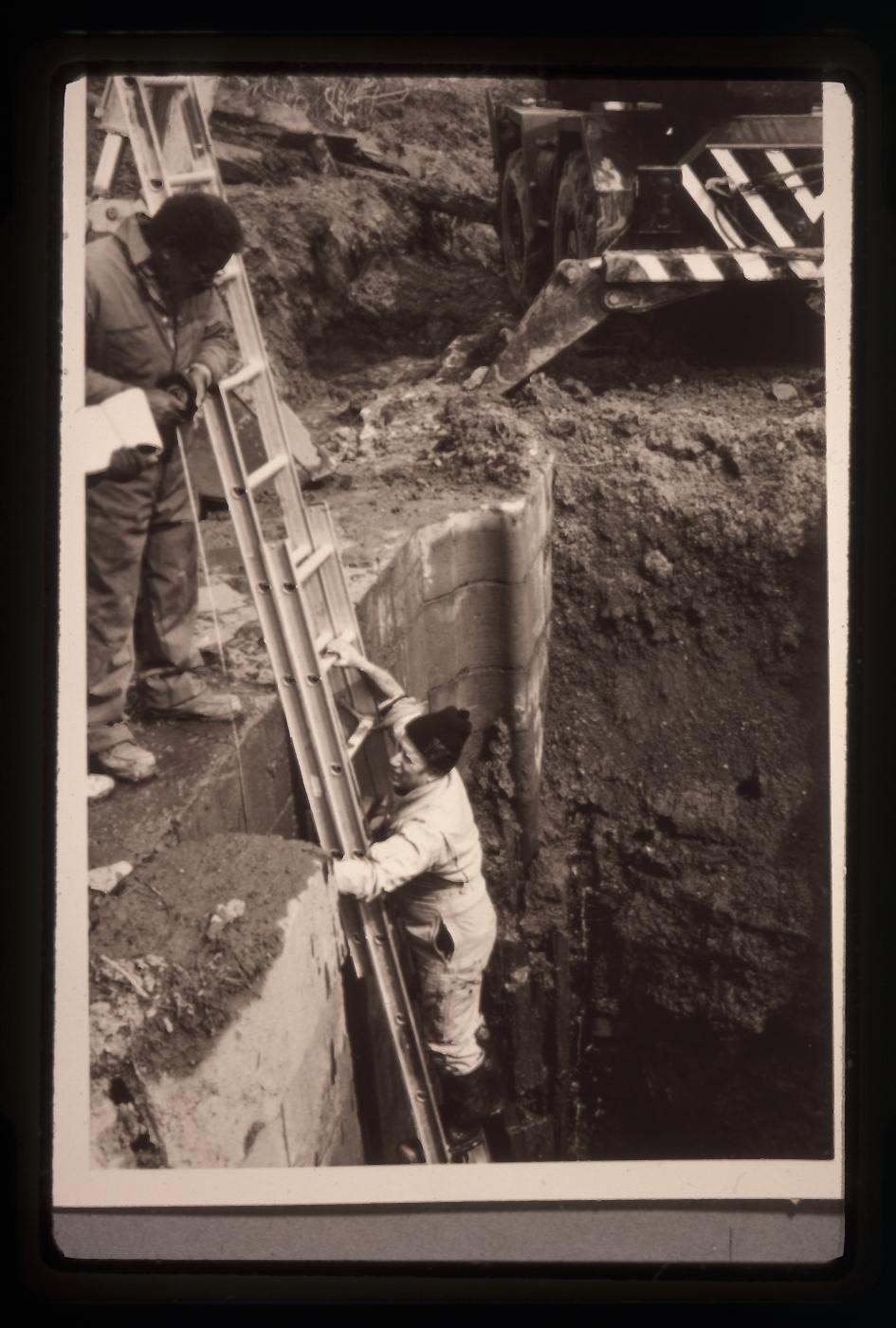

Archaeologists have excavated portions of the Alexandria Canal. In the late 1970s and into the 1980s, archaeologists uncovered a 90-foot section of the canal, including Lift Lock No. 1 (the tide lock). These archaeological investigations informed the design of present-day Canal Center and its Tide Lock Park, which includes a partially rehabilitated and reconstructed lock. Some canal stones were removed during excavation in 1985, marked with plaques, and placed in public areas throughout the city, including Beatley Central Library, Fort Ward Park, Rivergate Park, and Windmill Hill Park.

In 2024-2025, archaeologists uncovered the remains of Lock No. 4 and the third basin on the 900 Block of N Pitt Street. Alexandria Archaeology anticipated that the masonry remains of this large-scale piece of historic infrastructure may be preserved despite the development of a 1980s office building, and required the developers hire archaeologists to monitor and document the excavations. A sample of the cut stones were salvaged and stored in adjacent Montgomery Park for eventual re-use within a public waterfront park. View a 3D model of the excavated Lock No. 4 and third basin.

The canal’s Lock No. 3 and basin two are likely preserved one block to the east, under Montgomery Park. The remains of the north abutment of the aqueduct bridge are still visible on the Georgetown side of the Potomac River.