The Archaeology of Civil War Crimean Ovens

The Archaeology of Civil War Crimean Ovens

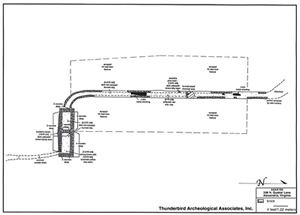

Crimean Ovens were underground heating structures built by Union troops during the Civil War to heat hospital tents. (Drawing by Wally Owen, courtesy of Thunderbird Archaeology.)

Stephen Potter, NPS National Capital Region Chief Archeologist, provided a reference to the MA thesis of Todd Jensen, on archaeological evidence of Civil War camps. The thesis contained a reference to a letter written by a Union surgeon describing a heating system for heating hospital tents. Wally Owen went back to the original letter and found a nearly exact description of the features found at the Quaker Lane and Quaker Ridge sites.

In November of 1861, Dr. Charles S. Tippler, Surgeon and Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac described how to build a heating system “...for warming the tents and drying the ground a modification of the Crimean oven, which has been devised and put in operation by Sr. McRuer, the surgeon of General Sedgwick’s brigade, appears to me to be the cheapest and most effective.” He goes on to describe the system:

A trench 1 foot wide and 20 inches deep to be dug through the center and length of each tent, to be continued for 3 or 4 feet farther, terminating at one end in a covered oven fire-place and at the other end a chimney. By this arrangement the fire-place and chimney are both on the outside of the tent; the fire-place is made about 2 feet wide and arching; its area gradually lessening until it terminates in a throat at the commencement of the straight trench. This part is covered with brick or stone, laid in mortar or cement; the long trench to be covered with sheet-iron in the same manner. The opposite end to the fire-place terminates in a chimney 6 or 8 feet high; the front of the fire-place to be fitted with a tight moveable sheet-iron cover, in which an opening is to be made, with a sliding cover to act as a blower. By this contrivance a perfect draught may be obtained, and no more cold air admitted within the furnace than just sufficient to consume the wood and generate the amount of heat required, which not only radiates from the exposed surface of the iron plates, but is conducted throughout the ground floor of the tent so as to keep it both warm and dry, making a board floor entirely unnecessary, thereby avoiding the dampness and filth, which unavoidably accumulates in such places. All noise, smoke, and dust, attendant upon building the fires within the tent are avoided; there are no currents of cold air, and the heat is so equally diffused, that no difference can be perceived between the temperature of each end or side of the tent. Indeed, the advantages of this mode of warming the hospital tents are so obvious, that it needs only to be seen in operation to convince any observer that it fulfills everything required as regards the warming of hospital tents of the Eighth Brigade, and ascertain by observation the justness of this report.

Learn more about Alexandria during the Civil War

The First Discovery – The Firebox End

The land where the first Crimean Oven was uncovered was on a residential lot on Quaker Lane which was once part of the plantation, "Cameron," owned by General Samuel Cooper. General Cooper was the Adjutant General of the U.S. Army (the second highest officer in the army) before the Civil War. When Virginia seceded, he resigned and became the Adjutant General of the C. S. A. Army. Because of his action, his property was confiscated by the federal government and one of the forts in the Defenses of Washington was built on his land. The Cooper house was torn down and the bricks used to construct the large powder magazine of the fort. The fortification was referred to as "Traitor's Hill" until 1863, when it was officially named Fort Williams. Federal army units camped in the vicinity of the fort and in many places throughout Alexandria.

Prior to development, the City, in accordance with the Archaeological Preservation Ordinance, required an archaeological investigation of the lot on Quaker Lane. It was likely that the remains of a Union camp were present because the property was just to the southeast of the site of Ft. Williams. Wally Owen, Assistant Director of Fort Ward Museum and a local authority on the Civil War, examined the area and observed how the property adjacent to the lot to be developed shows evidence in its undulating lawn of the raised regimental company "streets" with drainage ditches on either side, that are typical of long-term Civil War period encampments.

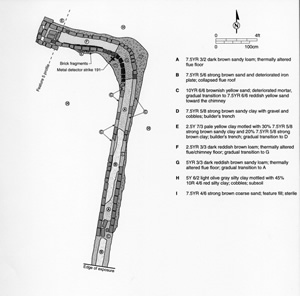

The developer hired Thunderbird Archeological Associates and the fieldwork was conducted during the summer of 2003 by archaeologists directed by Tammy Bryant. The owner had given permission for a local relic hunter to use a metal detector on the property and he found various Civil War period artifacts in addition to an area with bricks. He claimed to have removed “at least a hundred” bricks before the archaeologists began their work. The archaeologists uncovered a channel about 50 feet long, a foot wide, and about a foot below the ground surface edged on both sides by three courses of bricks. In three or four places thin sheets of metal, possible covers, were found crushed down into the bottom of the channel. The parallel lines of bricks descended down a slope and ended in a two course-wide brick rectangular structure about eight feet long, three feet wide and two feet deep. There was a partial dividing wall near the center of this box which might be the wall of the original box which was then expanded to double its size. The earth in the bottom of the box was reddened and baked almost as hard as a brick as was the dirt floor of the flue channel extending from the box. A layer of charred wood lay on the floor of the structure and was covered with a layer of fine sand about three inches thick. This probably was an ash pit that would have been below a fire where wood was burned. The fill soil of the entire feature contained artifacts dating to the Civil War and earlier, including Minie balls, a brass button from a New York Regiment, plus a brass and lead eagle breast plate. The end of the brick channel opposite the fire box was totally disturbed where the relic hunter had removed the bricks. The soil was scraped on each side of the flue to try to identify any remains of tent locations. The idea was that tents or huts could have been heated by hot air diverted from the flue channel. No evidence of structures was observed.

Archaeological Investigations at 206 North Quaker Lane (44AX193)

Tobacco importer Josiah Watson’s property, Stump Hill, was subdivided after he filed for bankruptcy in the late 1790s. Two roads were created through the property, providing access to the lots; one of these was today’s Quaker Lane. On the west of this thoroughfare lay the Cooper family plantation, Cameron, also known as Cooper’s Hill and, by Union soldiers, Traitor’s Hill or Fort Traitor (44AX199). Excavation here turned up a brick Crimean Oven, which likely would have heated the camp hospital tents. Also discovered was 19th-century artifact scatter, including bottle glass fragments mostly from alcoholic beverage bottles, metal hardware associated with uniforms and equipment, munitions, ceramics, and architectural materials. The high proportion of refined versus utilitarian ceramics indicated higher status personnel, that is, officers. Archaeologists purported that the 38th New York infantry regiment camped here; they were stationed in the area in the winter of 1861.

- Christine Jirikowic, Gwen J. Hurst and Tammy Bryant Phase I – Phase III Archeological Investigations at 206 North Quaker Lane, Alexandria, Virginia . Thunderbird Archeological Associates, Inc., Woodstock, Virginia, 2004.

- Public Summary

The Second Discovery – The Chimney End

In the summer of 2004, a property just to the south of the Quaker Lane project was to be developed. It was a lightly wooded row of backyards of modest houses built between 1940 and 1955. This property also had the potential to contain the remains of Union camps. John Milner and Associates archaeologists, directed by Joe Balicki, conducted the investigation. Through the use of metal detectors, and aided by a trusted local relic hunter, they found a typical scatter of Civil War-period dropped bullets, buttons, and other military accouterments, along with a number of small hearths indicating a light encampment. As the work continued, during the excavation of an epaulet, bricks were found. Further excavation uncovered another Crimean oven flue with the intact chimney end – the only part missing from the Quaker Lane site oven. The construction of this feature was nearly identical to the one previously found, except that the fire box end of this structure had been graded away, probably when the nearby house was built. Because the destruction of this feature could not be avoided due to development, it was decided to remove this structure to Fort Ward Museum for use in some future exhibition. The bricks were all numbered and photographed so the oven could be reassembled.

Archaeological Investigations for Quaker Ridge Housing (44AX195)

Five residential lots on approximately 2.5 acres were to be redeveloped into townhouses, thus archaeologists were required to study the site. Civil War-era artifacts suggested the presence of a soldiers’ camp: ammunition, buttons, buckles, cap insignia, knapsack parts, shoe nails, and a decorated pipe bowl. Further supporting this were eight features: seven hearths (five probably kitchen-related and two probably for heating tents) and a remnant of a Crimean Oven, which would have heated the camp hospital tents. The Crimean Oven remnant resembled that found at site 44AX193 on N. Quaker Ln. Archaeologists identified the site as the autumn-of-1861 New York militia camp, potentially that of the 38th New York infantry regiment.

-

Joseph Balicki, Bryan Corle, Charles Goode and Lynn Jones Archaeological Investigations for Quaker Ridge Housing (44AX195), Alexandria, Virginia. John Milner Associates, Inc., Alexandria, Virginia, 2005.