Archaeology at Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery

Archaeology at Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery

The goals of the archaeological investigations focused on the identification of burial locations to ensure protection during development, future maintenance of the site, and the recovery of information about the cemetery for use in the memorial design process.

In addition to important information about the cemetery itself, archaeologists discovered that, in the 19th century, the cemetery was dug through an important prehistoric site. While most of the tools are from the Archaic period, Alexandria's earliest artifact, a Paleoindian Clovis Point, was found here.

Site Report

Sipe, Boyd, with Francine W. Bromberg, Steven Shephard, Pamela J. Cressey, and Eric Larsen, The Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial, City of Alexandria, Virginia. Archaeological Data Recovery at Site 44AX0179. Thunderbird Archaeology, a division of Wetland Studies, Gainesville, VA and Alexandria Archaeology, Office of Historic Alexandria, 2014. (The report may be viewed by appointment at the Alexandria Archaeology Museum).

Learn more about the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial and its history.

The Cemetery

The primary goal of the archaeological investigations was to provide information to insure that all extant graves are protected during development of the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial and that the design reflects the historic character of this special place. Archaeological investigations conducted by URS Corporation in 1999-2000 and by Alexandria Archaeology in 2004 and 2007 identified locations of more than 500 of the 1,800 graves once located in the cemetery.

It is thought that at least half of the historic graves still survive on the property. In addition to the excavated areas, hundreds of graves are thought to remain in areas that are still protected under two concrete slabs remaining from 20th century structures, and below the asphalt and sidewalk of South Washington Street.

Excavations revealed the location of the graves, but archaeologists were careful to not disturb the burials, since they will be preserved on the site. Archaeologists were able to locate the grave shafts, or in some instances, the outline of the top of the coffins, by identifying subtle changes in soil color and texture. No grave can be associated with a particular person.

Historical records and archaeological information provide some understanding of the cemetery's historic landscape. A wooden picket fence surrounded the cemetery. The Army Quartermaster Corps supplied wooden headboards at the time of the burial. Each headboard was probably white-washed and had the name of the deceased written in black lettering. Several graves had stone markers, supplied by the families. A fragment of one stone marker was found during excavation. A small shed was situated on the site for tools and biers. Graves were kept “ever at the ready” by a three-man team of gravediggers who were freedmen themselves.

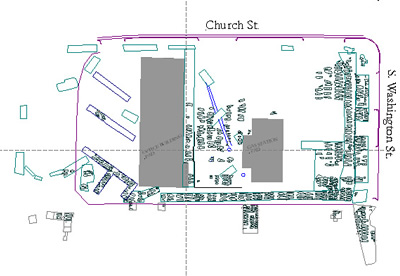

The gravediggers prepared each grave individually, and the graves were placed very close to one another in orderly rows. Archaeological investigations discovered lines of more than 50 graves extending north/south across the width of the cemetery parallel to South Washington Street. More than 46 rows of graves extend east/west parallel to Church Street. (The historic cemetery would have been larger.) A 12-foot gap between rows of graves along South Washington Street is believed to have been the entrance to the cemetery, and a carriage path extended westerly into the cemetery.

The deceased were placed in coffins that could be supplied by the family or purchased from the Army. Standard coffin sizes were produced at 2½, 4, 5, and 6-foot lengths for “destitute contrabands.” Fees were charged to others, at a cost of $2 to $5 depending upon size. The Gladwin Records, recording burials at the cemetery, chronicles chaplains officiating at some of the civilian services, while soldiers were buried with military honors.

The length of the grave shaft, or in some cases the coffin, was found through the archaeological work. While it is not possible to determine the gender of the deceased, children's graves are distinguishable by their small size. Analysis of the death records shows that more than half of those buried in the cemetery were under the age of ten.

When the City archaeologists encountered areas disturbed by earlier construction on the site, the upper parts of the burial shafts were often missing and the hexagonal outlines of coffins were found, sometimes just inches under the asphalt of the former parking lot. Further evidence of the desecration of some graves could be seen as coffin wood, coffin tacks, and, in some cases, human remains were found out of place, and some graves were completely graded away. White porcelain shirt buttons were also found. All artifacts associated with graves and human remains were recorded and left in place.

The hexagonal coffin shape is indicative of the traditional “shouldered” style common in late 18th and early 19th centuries. Archaeologists found a few of the coffin screws and tacks used to fasten the lid to the coffin box, and decorative hinges that allowed the top of the coffin to be opened for viewing of the deceased. They also found a fragment of a coffin handle, indicating that the individual may have been carried by mourners to the grave. Although no grave goods were discovered, one set of burials in the western part of the cemetery did have a covering of oyster shells. Many other pieces of ceramic and glass were discovered during the investigation, but there is no indication that they were associated with the graves, and they are likely to be trash associated with later activity on the site. Two Civil War-era bullets were also found during excavations.

1996-1998: Remote Sensing

In 1996 a documentary study was prepared, followed by remote sensing (ground penetrating radar and electromagnetic surveys) on the Old Town Mobil Station property. This work, conducted by personnel from Parsons Engineering Science, Inc., indicated areas of disturbance in the eastern half of the property, including utility lines, a tank field and a waste oil tank. These surveys also recorded at least seven north-south-running lines of subsurface anomalies that had the potential of being graves. The report on this investigation concluded, “Given the high potential for the existence of burials beneath the asphalt, especially in the rear of the lot, it is recommended that all design and construction plans avoid subsurface impacts in this area.” The report included the recommendation that if there are plans to impact the property, an archaeological investigation should be conducted to ascertain the nature of the anomalies and determine if burials are present.

In 1998, URS Corporation and Geosight, Inc. conducted a geophysical, or remote sensing, survey on the VDOT (Virginia Department of Transportation) land to the south and west of the gas station. One area was identified as having the potential for containing graves. The report recommended that archaeological excavations be conducted to better understand the nature of the soil stratigraphy and determine if graves were present.

1999-2000: Excavations on the VDOT Property

Excavations undertaken by archaeologist with URS Corporation established that burials were extant in the VDOT land on the southern part of the site. A total of 78 graves were identified. Based upon this work, the cemetery was determined eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

In this phase of work, archaeologists opened nine trenches in one area and twenty-five excavation units in another. A small area was stripped using a backhoe, and then excavated by hand to identify the location of grave shafts. The goal was to identify the location of grave shafts, but not to excavate the burials.

In addition to the grave shafts, other archaeological discoveries were made. On one part of the property, the soil stratigraphy showed multiple layers of fill extending to a depth of more than 13 feet. This was possibly the result of mining clay by the late 19th-century brick-making company, located on the adjacent block to the northeast, which once owned this property. Other finds included the articulated skeleton of a cow, and a well-preserved upright wooden barrel without a lid, possibly the remains of a well or privy. Over 1,300 prehistoric lithics were recovered from the plow zone and fill soils.

2004: Archaeological Testing on the Gas Station and Office Building Lots

Alexandria Archaeology undertook archaeological testing on the Gas Station and Office Building lots in 2004, to obtain general information about the depth of the fill across the property, the presence or absence of buried surface soils, and the limits of the cemetery. Results from this phase of work were used in planning for the demolition monitoring and data recovery phases of work, and will be ultimately used for the design of the park.

The businesses were still operational, so testing was limited to areas of the parking lot. Fourteen trenches were excavated and the locations of 45 burials were identified on this portion of the site. In addition, the buried surface layer yielded additional evidence of Native American occupation.

2007: Archaeological Excavations

After the businesses were closed, City archaeologists and a temporary crew carefully excavated extensive areas of the site in order to determine areas where graves no longer were preserved and where ones still remained. Care was taken so that, once the grave shafts were located, the burials were not disturbed. The archaeologists located more than 400 additional graves during the 2007 field season, bringing the total number of burials identified to more than 500. The burials were in fairly regular north/south running rows, all in the traditional Christian east-west orientation. The work also resulted in the discovery of the location of a possible carriage path into the site with an entrance on South Washington Street.

The investigation confirmed that construction of the gas station in 1955 and office building in 1960 had significant impact on the cemetery. Most of the original knoll was graded and the original ground surface of the cemetery only remains in a few places. This earlier construction disturbed the graves in some areas. Where the original ground surface survived along the western portion of the property, excavations yielded a few historic artifacts, including one grave that was marked on the surface with large oyster shells. Excavations also showed that, in the 19th century, the cemetery was dug through a significant prehistoric site. Many lithic (stone) artifacts were found, mostly dating to the Woodland and Archaic periods along with one Clovis point from the earlier Paleoindian period.

Following the excavations, over 20 loads of clean fill dirt were brought onto the site to create a 2-foot deep protective buffer over the top of the graves.

Research and Analysis

The work of research and analysis began long before any excavations took place. A map documenting locations of graves in the cemetery was produced and guidelines prepared to make sure that the graves were protected during construction of the memorial. A database of recorded information from each individual grave was compiled and linked to the site map to create a tool with which we could ask further questions and look at the site in spatial terms. Archaeologists were able to determine complete measurements (length and width) for 243 graves. Of these, 53 (or 18%) appear to be graves of children. Artifacts were catalogued and photographed, and a site report was completed by Alexandria Archaeology staff. An historian conducted research and wrote a history of the cemetery. Funds have been provided by a Save America's Treasures grant for publication of the history and preparation of additional web materials.

The Clovis Point

When the cemetery was in use in the 1860s, the gravediggers were probably unaware that they were digging into an important Native American site. Archaeologists discovered thousands of Native American stone artifacts, indicating that the site was used for the manufacture of stone tools over a period of thousands of years. The oldest artifact ever found in Alexandria, a 13,000 year-old Clovis spear point, was recovered here in 2007. A buried portion of the western slope of the cemetery continues to protect a significant Native American archaeological site.

This was the first time that archaeologists found a Clovis Point in Alexandria. The Clovis Point is a diagnostic marker for an era known to archaeologists as the Paleoindian period that lasted from as early as 13,000 to about 10,000 years ago. During this period, when mammoths still roamed North America, small bands of Native Americans moved frequently through this area, hunting and collecting plant resources. The Clovis Point is the first evidence of their presence in Alexandria.

In the Archaic period, from 3,000 to 10,000 years ago, several stone tools and thousands of quartz and quartzite flakes from the tool-making process were left on the site. Archaic period tools found at Freedmen’s Cemetery were identified as Morrow Mountain II and Halifax points, and a possible Rice Lobed point (Middle Archaic), and Savannah River, Hellgrammite and Calvert points (Late Archaic). The Archaic period saw the continuation of hunting and foraging lifestyle of the Paleoindians. They lived in seasonal camps while fishing and gathering shellfish. The Archaic Period also brought about the development of new tools such as ground stone axes, mortar and pestles, and weighted spear-throwers called atlatls.

A few Woodland period artifacts, including a Potts point (late/middle woodland), were also found, dating from 400 to 3,000 years ago. This period brought about the beginnings of agriculture, with Native Americans cultivating corn, squash and beans. In this period, they began manufacturing pottery, and some established more permanent villages on the shores of larger rivers. The use of horses and the bow and arrow began in the late Woodland period.

The Alexandria Clovis Point, made of quartzite, was broken during manufacture. According to Fairfax County Senior Archaeologist Mike Johnson, an expert in archaeology of this period who first identified the point, the tip broke off during late stage lateral thinning, when the knapper was trying to remove a small lump near the tip. Clovis points are usually made of high-quality chert or jasper, but the tool-makers of this period were highly competent and could adapt their technology to other stone which is harder to work, such as local quartzite cobbles.

Clovis is identified by its ground, concave base, bifacial blade, and the fluted channel, that allowed the point to be hafted or attached to a spear. Clovis points were manufactured and used by bands of hunters as they roamed the grasslands and open conifer forests that would have been present in Northern Virginia as the glaciers from the last Ice Age began to melt. The McCary Fluted Point Survey records every occurrence of this important artifact type in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2007, around 1,000 Clovis points have been found, including seven in neighboring Fairfax County. Most were made of chert and other imported stone rather than the local quartzite.

The early date, ca. 13,000 BP (before present), comes from a new look at radiocarbon dates related to other Clovis sites in various parts of the country. Clovis is named after a site in Clovis, New Mexico, where a distinctive fluted point and other tools were found in 1932 in association with a woolly mammoth kill. Clovis sites were until recently dated to ca. 11,200 BP, but new research has pushed these dates back by nearly 2,000 years. Other sites, such as Cactus Hill, point to the presence of even earlier pre-Clovis sites in Virginia.