Black Education in Alexandria, Part 1

Black Education in Alexandria: A Legacy of Triumph and Struggle

Black Education in Alexandria

Main page: Black Education in Alexandria: A Legacy of Triumph and Struggle

Part 1: Early African American Education in Alexandria,1793-1870

Part 2: Separate and Not Equal, 1870-1960

Part 3: The Legacy of Segregation, 1954-2023

More Information

Summary: Early African American Education in Alexandria. 1793-1870

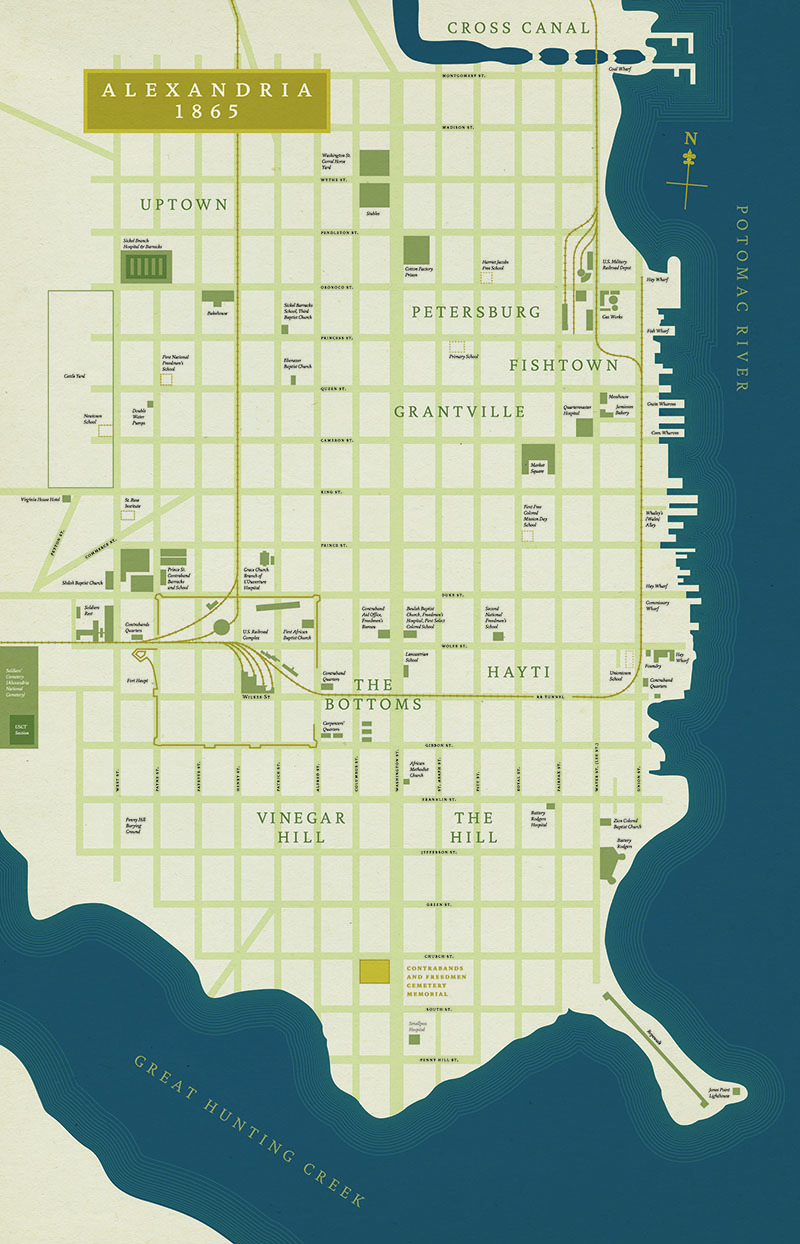

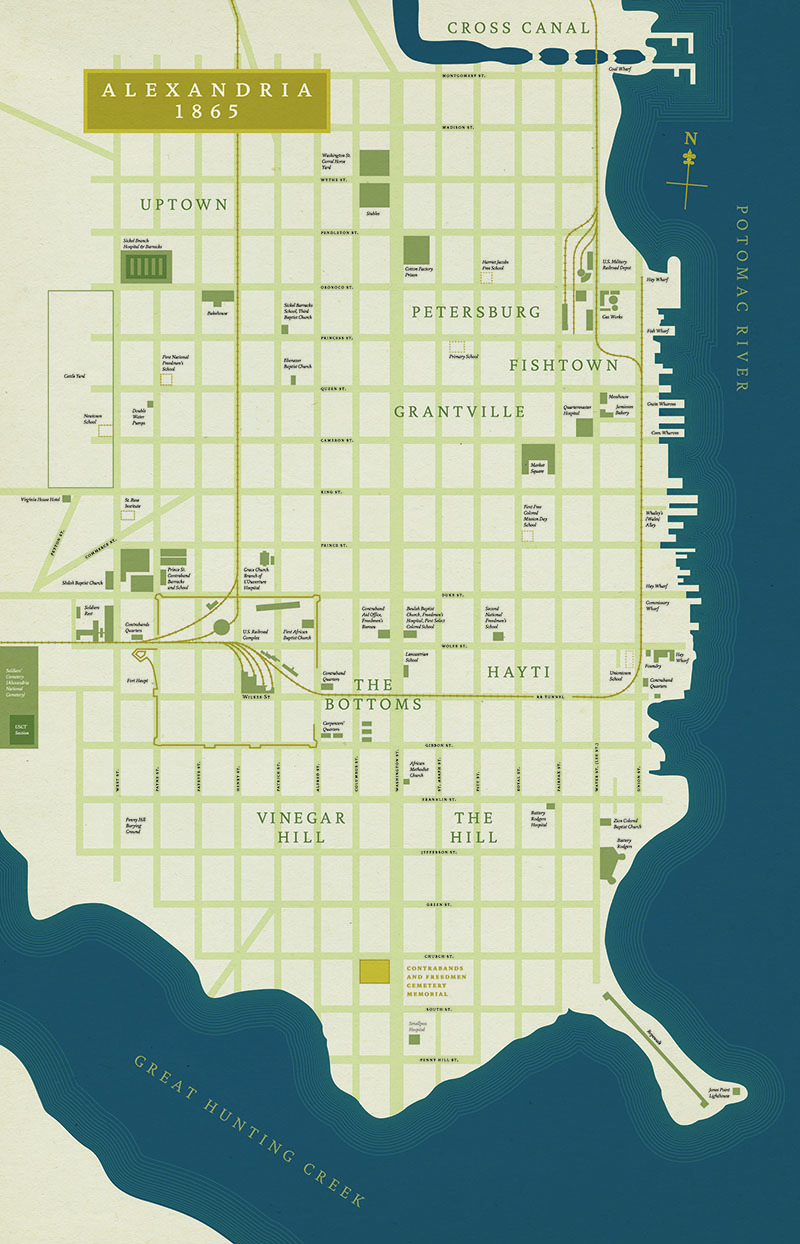

In the 19th Century, most African Americans would not have lived in places where they could access a formal education, but the District of Columbia was an exception. Because of Alexandria’s Capital status after becoming part of D.C. in 1789, the city had a comparatively vibrant education scene for both free and enslaved Black people as early as 1793.

Learning was precious to the Black community, and it was alternately encouraged and tolerated by white Alexandrians. But once Alexandria’s boundaries receded to Virginia in 1846, schooling was suddenly forbidden. Local white authorities quickly moved to enforce Virginia’s unforgiving laws, striking terror into the heart of the Black community as they did. Given this history, it is not surprising that soon after Union boots hit the docks on Alexandria’s shore in 1861, African American schools flourished.

Four years after the Civil War ended, Virginians ratified a new constitution that established a statewide public education system, an achievement sullied by white fears over the mixing of Black and white children. In the halls of the statehouse, African American lawmakers offered full-throated arguments for an integrated system, which they saw as the only path to true equality, but they simply could not overcome ingrained prejudices. This was a recurring theme that would plague education into the 21st-century. Unfortunately, the lawmakers were right, and a thriving Black education scene was hobbled after white authorities took over.

Under the Protection of the Capital 1789-1846

Alexandria became part of the nation’s capital in 1789, and the political distance from Richmond during these years created space for learning for both free and enslaved Black people. Initially, Quakers and white ministers offered educational opportunities to Black Alexandrians. By the second decade of the 1800s, Black teachers were establishing schools and earning salaries. Their successes ended abruptly after Richmond took control in 1846.

As early as 1793, Henry Wilbar, a white Quaker living in Alexandria, was teaching Black children and adults. As of 1798, Wilbur was operating an evening school on Prince Street where he taught Black boys ages 10-14 English and arithmetic.

Prior to the War of 1812, there were at least two schools for Black children in the Southeast Quadrant of Old Town. Mrs. Cameron ran a primary school out of her house on the corner of Duke and Fairfax Streets. She was white, and she charged a fee. Likewise, Mrs. Tutten, also white, charged a fee to instruct Black children in her house on the corner of Pitt and Prince Streets.

The same year the U.S. went to war with Britain, in 1812, a free school for Black children opened. Rev. James H. Hanson, the white pastor at the African Methodist Episcopal Church, along with an association of free Black Alexandrians, started a school in the Alexandria Academy building between Wolfe and Wilkes Streets. They had the support of an “enlightened and benevolent” white community who provided “aid and encouragement.” [Endnote 1]

The popular school was “composed of the most substantial colored people of the city and was maintained with great determination and success for a considerable period.” More than 300 students attended the school. The instructor was able to handle large class loads by employing what was called the Lancastrian Method that relied on older youth to tutor the younger children. [Endnotes 2,3]

Sometime in the early 1800s, Samuel Plummer, a white member of the board that governed the Washington Free School, held a night school for African Americans on Fairfax Street where he taught them to read and write, as well as arithmetic, geography, and music.

Unlike those who belonged to the free schools movement, the majority of white society viewed education as a privilege. In Colonial America and after the Revolution, it was considered the parents' responsibility to pay for their children’s schooling. People of both philosophical persuasions lived in Alexandria. However, the city was predominantly Christian, and both Protestants and Catholics allowed white churches to teach Black and poor white people to read as a matter of religious instruction. A number of white congregations in this city offered such instruction free of charge to small groups of Black children and adults.

One of the larger church schools was run by the nuns at St. Mary’s Catholic Church who taught Black children spelling, reading and Christian doctrine.

After a short time, Black congregations also started “sabbath schools.” [Endnote 4]

It was not long before educated Black Alexandrians started making a living teaching. One well-known African American educator, Alfred Parry, who had been a pupil of Rev. Hanson’s, established a night school for Black adults. Soon after, he opened a thriving day school called Mount Hope Academy to teach enslaved boys and girls. His school was attended by 75-100 children whose enslavers provided permission and paid tuition. [Deeper Dig 1]

Around the same time, African American Sylvia Morris held a primary school in her home on Washington Street.

Joseph Ferrell, “a man of decided abilities” who was “a baker by trade and a leading spirit among the colored people,” offered schooling in an alleyway between Duke and Prince Streets. Ferrell had to close his school when he “was sent to the penitentiary for assisting some of his race in escaping from bondage.” [Endnote 5]

The Impact of Nat Turner’s Defiance

Nat Turner’s 1831 violent cry for justice exposed the lie that the enslaved were content and awakened a profound white fear. In response, the Commonwealth forbade the education of Black people whether they were free or enslaved.

Ever since 1818, Alexandrians held a recurring debate over whether to return to Virginia. The Black community did not want the City to retrocede. After Turner’s revolt, some free Black Alexandrians attempted to assuage white anxiety by proactively signing a petition promising loyalty to local officials. [Deeper Dig 2]

At first, their brave pitch seemed to work. Parry was able to keep his schools going “even after the severest period of the persecution which followed the Turner insurrection in South Hampton County and the riots in Washington and other cities, from 1831-1835.” [Endnote 6]

But as time wore on, white Alexandrians interests grew more and more in alignment with Richmond and the rest of the South.

In 1837, when Virginia revoked the right of Black people to gather in groups, Alexandria followed suit immediately passing a similar ordinance. Mayor Bernard Hooe tried to use the new rule that would not allow Black people to gather “under the pretense or pretext of a religious meeting, or for any amusement” to shut down Parry’s school. Other Black schools were also harassed by white officials.

“In Alexandria the schools were subjected to annoyance and restraints under the provisions of the city ordinance prohibiting all assemblages, day or night,” according to an 1870 report on Black schools in the District before and during the Civil War by M.B. Goodwin.

The once supportive atmosphere in Alexandria was changing. “The hostility to the instruction of the colored people had become so strong that the children were obliged to conceal their school books on the street, and to dodge to and fro like the young partridges of the forest,” Goodwin wrote.

Around the same time, Horace Mann, an ardent abolitionist, was leading a Common Schools Movement in Massachusetts. He wanted to make education available to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay, by using public funds to open schools in every community. By ensuring students of all incomes and abilities learn together, he argued, there would be more economic mobility, and we would have better citizens and a more stable society - one in which class no longer mattered. [Deeper Dig 3]

As they had with Thomas Jefferson’s attempts to establish a limited free education for boys in the Commonwealth, Virginians clashed with Mann’s philosophy. Alex De Toqueville’s praise for the individual and argument that wealth, status and privilege were the result of hard work and good choices made more sense to a society steeped in classism and racial hierarchy.

1846: Despotism Descends

When the white men of Alexandria voted to reunite with the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1846, a swift persecution of the Black community followed. In Alexandria,

“The constables of the city were at once ordered to disperse every colored school, whether taught by day or night, on the weekday or on the Sabbath, and the injunction was most zealously executed. Every humble negro cabin in which it was suspected that any of these dusky children were wont to meet for instruction was visited, and so stern and relentless was the rule that the free colored people dared only in a covert manner to teach even their own children, a colored person not being allowed to read openly in the street so much as a paragraph in a newspaper. Some used to meet in secluded places outside the city, and, with sentinels posted, hold their meetings for mutual instruction, those who could read and write a little teaching those less fortunate. Thus, all the education which they could give their children was such as was dispensed by stealth in dark corners, except those who were able to send their sons and daughters to Washington and elsewhere, as many, by the most extraordinary exertion, continued to do through the next 14 years. But under the iron despotism of the ‘Virginia Black Code,’ those who sought their education abroad were expatriated, for the law strictly forbade such ever to return with their intelligence to their homes under penalty of fine or stripes.” [Endnote 7]

Free Blacks had opposed retrocession, but with no rights at the ballot box, they could not give voice to their desires. A significant number left town after the whites decided to rejoin Virginia, and over the next fifteen years further repression from Richmond compelled even more African Americans to leave Alexandria. [Endnote 8]

Liberation Upon the Tips of Bayonets

On Thursday, May 23, 1861, Virginia seceded from the United States. “The people of Virginia voted with substantial unanimity….to repeal the ratification of the Constitution of the United States of America,” wrote Edgar Snowden Sr., editor of the Alexandria Gazette.

At 5 a.m. on Friday, May 24, Union troops arrived by land and river. They took over the railroads, the telegraph and government offices, and raised the U.S. flag on Market Square. As the U.S. Army prepared Alexandria to be a base of operations, many of the city’s aristocratic families fled. [Endnote 9]

Mary Chase awoke to find she was alone in the house, abandoned by her enslavers. She “quickly appreciated the nature of the wonderful event,” and by September, she opened The Columbia Street School where she taught 25 formerly enslaved pupils each year from 1861 - 1866. [Endnote 10]

Within a month, Jane Crouch and Sarah A. Gray opened the St. Rose Institute for Black students on West Street between King and Prince.

Thousands of Black people fleeing enslavement were pouring into Alexandria, liberating themselves while causing an acute refugee crisis in the city. They were first called “Contrabands of War” because they were considered property, but later they were recognized as Freedmen. When they arrived, many were eager to obtain schooling. In some cases, the refugees set up schools to teach one another, in other cases, they went to schools organized by Alexandria’s Black community.

At the same time, teachers from Pennsylvania to Maine - the majority of them white - made their way to Alexandria. They had the financial backing of benevolent societies, churches and abolitionists who wanted to establish free schools for the African Americans who had made their way to freedom.

To help meet the needs of the freedmen, African American Rev. Clem Robinson, who had attended college and theology schools in the North, opened the First Select Colored School on Jan. 1, 1862, in rooms at Beulah Church. Among the trustees and founders were a who's who of Black Alexandrians who had been free before the war and who would continue to advocate for education, including Rev. G.W. Parker (Third Baptist), George Seaton, George W. Simms, Charles Watson, Anthony S. Perpener, George W. Bryant, Hannibal King, George P. Douglas, John Davis, J. McKinney Ware and James Pipe. Parker and Robinson were instructors, along with Mrs. Robinson and Ms. Amanda Borden. The team of experienced Black teachers offered a primary education, but also a theology school and a normal (teaching) school. More than 700 students enrolled in the first year with 15 attending the Normal or Theological schools.

Some of the very first freedmen to cross into Alexandria were given shelter in the old Alexandria Academy building on Washington Street. Leland Warring, who would go on to pastor Shiloh Baptist Church, was among them. In Nov. 1862, Warring opened a school for his fellow freedmen in the Academy’s classrooms. The following February, the school moved to the newly opened “Freedmen’s Home” on the corner of Prince and Royal Streets. The school became known as “The First Free Colored Mission Day School.” [Deeper Dig 4]

Within months Black teachers opened more schools to support the growing thirst for knowledge:

Charles Seals had a school at 81 Prince Street; Mary Simms opened a night school on Duke Street; William Harris and Richard Lyles, both Black Alexandrians, held a day and night school on Princess Street between Pitt and St. Asaph called The Primary School; and Anna Bell Davis and Leannah Powell, also Black, started the Newtown School and only charged students who could pay, the rest learned for free.

Alexandria’s Black community was able to respond quickly to the needs of newly self-emancipated African Americans because of their long history of investing in education. “These schools were the first to be set up in the nation, and to the honor of the colored people, be it said, were established wholly by themselves. They were private, in part pay schools, and a very large majority of the scholars, from first to last, were contrabands.” [Endnote 11]

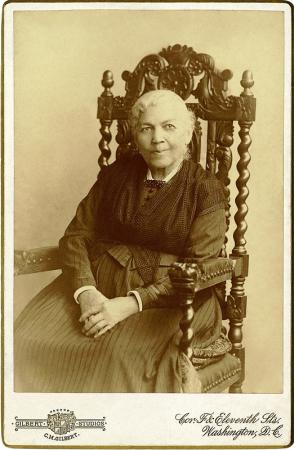

At the same time, skilled people backed by the Northern benevolent societies were getting to work meeting the needs of Freedmen. Among them was Harriet Jacobs, a formerly enslaved Black woman, whose first impressions of Alexandria after arriving in 1862 were lukewarm:

“There were other places in which I felt, if possible, more interest, where the poor creatures seemed so far removed from the immediate sympathy of those who would help them. These were the contrabands in Alexandria. This place is strongly secesh; the inhabitants are kept quiet only at the point of Northern bayonets. In this place, the contrabands are distributed more over the city.” [Endnote 12]

Jacobs went North to raise money to start a free school for those who settled in a neighborhood known as “Petersburg.” Upon her return she discovered that locals had raised $500 and built a “roughly-finished house for their school and meetings.” On January 11, 1864, The Jacobs Free School opened at this location. Jacobs, her daughter Louisa, and several white Northerners taught 170 students with ongoing support from the New England Freedmen's Aid Society.

Corp. L.A. Bermore, who was white, worked with Nancy William, a Black teacher, to open a free school called the Union Town School. It was located at the intersection of Wolfe and Union Streets. They taught about 80 students a year.

As the benevolent societies reached deeper into Alexandria more schools opened:

- Freedman’s Chapel

- Fort William School

- First National Freedman’s

- The Pennsylvania Freedmen's Relief Association at Zion Wesley Church

Non-Unionist white Alexandrians didn’t appreciate the waves of formerly enslaved people flooding the town. They resented the self-emancipated Blacks and barely tolerated schools set up by the Black Alexandrians they knew, let alone the newly arrived. But for the white people sent by northern groups they harbored an ice-cold dislike, refusing to lodge or even feed them. White parents let their children throw rocks at the teachers and their charges. A few of the older white residents continually registered frivolous “nuisance” complaints with the authorities in the vain hope the schools would be shut down. [Endnote 13]

Arrival of the Freedmen's Bureau

A few weeks before the end of the war in April 1865, an Act of Congress established a Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands to manage the needs of freedmen. Money from the sale of confiscated confederate properties was intended to support their programs.

After Lincoln’s death, on May 29, 1865, President Andrew Johnson betrayed the Freedmen’s Bureau by giving the rebels amnesty and allowing them to reclaim their confiscated lands. This left the Bureau with scant funds to operate, so they tried to make a meaningful contribution by prioritizing education. They streamlined aid from the benevolent societies and paid for the construction of school buildings. The Bureau’s leadership also wanted to establish training schools for teachers to standardize instruction. In Alexandria, with the help of the Black education establishment, the Bureau successfully opened a school that included a teacher training program.

On April 18, 1865, the First National Freedman’s School opened on Cameron between Payne and West Streets. A year later it moved to the corner of Payne and Queen Streets. (This was a partial tuition school.)

St. Patrick’s School for Black children opened on May 1, on Patrick Street.

Black teachers opened the Second National Freedman’s School on June 14, on Wolfe Street between Royal and Pitt, a partial tuition school with a very good reputation.

In Alexandria, the third, fourth and fifth national schools were opened by benevolent societies. In addition, two schools were being run out of L'Ouverture Hospital, another two in the Barracks Buildings, and one at Battery Rodgers.

Black Alexandrians opened two tuition schools: the New Primary School on St. Asaph between Wilkes and Gibbon Streets; and the Washington Street School that operated from a house at 65 Washington Street.

With so many free schools opening in 1865, Rev. Robinson’s First Select Colored School experienced a drop in participation, so they stopped charging fees and also became a free school.

About this time, George Seaton, a Black Alexandrian who had been free before the War, founded the Free School Society of Alexandria (FSSA). Seaton and leaders from the Black community launched a series of public meetings to drum up support to erect two new school buildings for free schools. Although many members had meager means, they managed to raise $1,600 and in 1866 paid for two building lots in The Bottoms and Uptown neighborhoods. [Endnote 14, Deeper Dig 5]

The FSSA worked with the Freedmen's Bureau to pay for the buildings and, in October 1866, the Bureau hired Seaton, a skilled carpenter, to construct one of the school houses on S. Pitt Street between Franklin and Gibbon.

In June of 1867, the Bureau contracted Seaton to build the second school on Alfred Street between Princess and Oronoco. He was also paid to build 200 desks and eight tables. The buildings were “very comfortable” and could seat up to 400 students. “The estimated value of the Alfred Street house and lot came to $7500, the other $6000.” [Endnote 15, Deeper Dig 6]

Once in operation, a total of 500 students enrolled at both schools. At the same time, the Alexandria Normal School - a training ground for teachers sponsored by the National Freedmen’s Relief Association - opened. At normal schools, children in primary and secondary levels were instructed together with teacher candidates who learned through practice. These schools were taught almost exclusively by white instructors from the North. [Endnote 16]

In addition to the free schools, Sarah A. Gray, of St. Rose Institute, opened The Excelsior School, another fee-based school, and taught an average of 70 Black students a year.

In his 1870 report to Congress, Goodwin wrote, “the colored children of the city have had vastly better school privileges than the white.”

With each advancement white resentment grew. Some Alexandrians, concerned over how slavery and the confederate cause were being portrayed in these schools, continued to ostracize the Northern teachers. While there were small pockets of support among Alexandria’s unionists and new northern immigrants, Goodwin wrote that most of the white residents were “strongly and even bitterly opposed” to helping the Black community. [Endnote 17]

The two schools built with Black labor, paid for by the Freedmen's Bureau on land owned by Black Alexandrians, and operated by a Black Board of Trustees, would become part of Alexandria’s public education system after 1870. White City authorities continually tried to obtain ownership of the real estate and the buildings. Then they neglected the buildings until they were in such disrepair that one burned in a fire and the other was too dangerous to use. In 1919, The City of Alexandria used taxpayer dollars for the first time to buy a lot and build a free school for Black children. The school - Parker-Gray primary school - was an empty shell when teachers entered it. The Black community stepped up to buy the equipment they needed to teach the students. It opened in 1920. Until then, Seaton and Hallowell school buildings were the only schools for Black children in the city. When Parker-Gray primary school opened it was the sole school for Black children in the City of Alexandria. [Deeper Dig 7]

Virginia Establishes a Public Education System

During the Era of Reconstruction that began at the end of the Civil War, former slave states had to create “reconstructed governments,” hold state conventions, and write new constitutions. In Virginia, 24 African American men were elected as delegates. Alexandria’s George Seaton attended an important meeting in Richmond in April 1867 that directed delegates to ensure a system of free schools would be established. They were successful and the new constitution obligated Virginia to support free schools for all children.

On July 6, 1869, Virginians ratified the constitution instituting the first statewide public school system in the history of the Commonwealth.

Virginia’s Superintendent of the Freedmen's Bureau Schools, Razla Morse Manly, reacted, writing that during the convention, the education system had been “standing on the table of a sick man for 15 months” receiving blow after blow from those who opposed public schools.

“The patient’s dislike for the medicine and hate for the doctor that compounded it, may retard and somewhat modify the effect of the dose, but it cannot destroy it” because “ample provision” was made in the constitution for the “permanent support of a comprehensive system of public free schools” by setting aside some of the state’s tax revenue to pay for education.

Manly had spent enough time in the state to know that Virginia’s “wealthy and aristocratics” would oppose and try to slow the movement, but, he said,

“It will certainly go forward until the free school shall be as common, as excellent, and as honored as before the war; it was scarce and contemptible. For the first time poor children as well as rich, regardless of past history or present condition were able to enjoy schools. The future of education in Virginia has never looked so hopeful for the poor and ignorant of both races as at the present time.”

On January 25, 1870, the military turned over control of Alexandria to civilians.

When the General Assembly met the next month, Rep. Seaton (R-Alexandria) was there. He sat on the Committee of Schools and Colleges and when the backlash against integrated free schools ginned up, Seaton, along with 30 other Black lawmakers, argued for a system built on equality. [Endnote 18]

In the end, the General Assembly agreed to a comprehensive school law that created the office of Superintendent of Public Instruction and a State Board of Education. The new officers would appoint local superintendents who could hire teachers and run the schools. What they did not agree to was a mixed school system. Seaton and the other Black lawmakers were not able to overcome the resistance from their white counterparts who feared relationships could develop between Black and white students if they learned together. Their hardcore adherence to racial hierarchy was “as solid as the primitive rocks of the Alleghenies.” [Endnote 19]

Virginia’s public school system was segregated from its inception.

Part 1 Endnotes

Endnotes

- Special Report of the Commissioner of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia: submitted to the Senate June 1868, and to the house with additions June 13, 1870, by M.B. Goodwin p. 282-.293; and Alexandria African American Heritage Park, Visitors Guide, VA. Ref. 975.5296 Alexandria Special Collections. It was either called the “Free Colored School” or the “Washington Free School.”

- Goodwin, Special Report, June 13, 1870.

- Alexandria Gazette, May 27, 1812, p.2.

- From the 1820s onward, the sisters of Charity (St. Mary’s Church) operated a small but “excellent” school for colored girls. They also maintained a large Sunday school for colored children where they taught spelling, reading and the Christian Doctrine. At the same time, the Sisters ran a large boarding school for white girls in a brick building on the corner of Duke and Fairfax Streets known as The Old Brig. Also, in 1916 St. Joseph’s Catholic Church on N. Columbus Street opened a school for Black students.

- Goodwin, Schools of the Colored Population, p. 283-285

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Cession and Retrocession of the District, Virginia Places, Boundaries No. 17; and “Many of the free colored people fled precipitately to Washington and to the North at the time of retrocession;” Goodwin, Schools of the Colored Population, p. 285.

- Alexandria Gazette, May 25, 1861, Extra Edition, p. 2.

- Goodwin, Schools of the Colored Population, p. 285.

- Ibid, p. 285.

- “Life Among the Contrabands,” by Harriet Jacobs, The Liberator, Sept. 5, 1862, p. 3.

- Goodwin, p. 293.

- Ibid, p.2 92. The land was purchased with $800 raised from freedmen at public meetings in 1866 organized by the Free School Society. George Seaton was the Founder and a member of the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees, according to Alexandria’s Deed Book at the Alexandria Library, Special Collections.

- Ibid, p. .292.

- "The Freedman’s Bureau and Negro Education in Virginia," William T. Alderson, The North Carolina Historical Review, Jan. 1952, Vol. 29, No.1, pp. 64-90. “The normal school was to teachers what theological, medical and law schools were to clergymen, physicians, and lawyers. While they could not give people brains, or qualify those naturally unfit for those professions, they were very properly demanded by public sentiment for admission to them.”

- Goodwin, Schools of the Colored Population, p.285; and Education Pioneer Sarah Gray, Alexandria Times, March 3, 2022.

- There were 30 Black lawmakers serving in the General Assembly in 1869, Encyclopedia of Virginia, African American Legislators in Virginia.

- "The Freedman’s Bureau and Negro Education in Virginia," William T. Alderson, The North Carolina Historical Review, Jan. 1952, Vol. 29, No.1, pp. 64-90. George Seaton voted against the public school bill because it required schools to be segregated, however, he truly believed in and wanted a public school system. [Read more: Remaking Virginia: Education; Biography of George Seaton.]

Deeper Dig

- M.B. Goodwin's report “Schools of the Colored Population” states that Alfred Parry, who was born a slave in Alexandria in 1805, was thrown into the Potomac by his mother "in her desperation" when enslavers were going to sell them separately. Parry was rescued and his mother "soon after" bought her freedom and then his. Parry’s manumission cost $50. [p. 283]

- Learn more about the 46 Petitioners in this video by Dr. Garrett Fesler, Alexandria Archaeology Museum

- Horace Mann died in 1859, before the Civil War broke out. Catholic immigrants and the Catholic Church were the biggest opponents to the Common School Movement because even though the schools were non-sectarian, Catholics worried it would spread Protestantism. Thomas Jefferson's version of public education didn't include women or Black people and reflected the hierarchy in Southern Society. [Read More: Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling; Thomas Jefferson’s Bill for Establishing a System of Public Education, ca. October 24, 1817.]

- Leland Warring was the father of Rev. Henry H. Warring. Both were pastors of Shiloh Baptist Church, but Henry was pastor when Alexandria lynched Benjamin Thomas on Aug. 8, 1899. Henry Warring baptized Thomas two years earlier when he was 14 years old, according to news accounts. Warring also gave Thomas’ eulogy at his memorial service, attended by more than 600 African Americans from Alexandria and Washington, D.C., who came to protest the lynching and to remember Thomas.

- The following were the first trustees who requested permission to charter the two free Black schools: Gustavus Adolphus Lumpkins, President; George Seaton, George W. Bryant, Anthony L. Perpener, Hannibal King, James Piper (Vice President), George P. Douglass, John H. Savis, Samuel W. Madden, J. McK. Ware, Charles Watson, George W. Parker, Clem Robinson, and George W. Sims.

Researched and written by Tiffany D. Pache for the Alexandria Community Remembrance Project.