Joseph McCoy Remembrance Walk

Joseph McCoy Remembrance Walk

The signs were in place from April 10-24, 2024

The Alexandria Community Remembrance Project marked the places in this city that were important to the story of the life and death of Joseph McCoy, an 18-year-old native Alexandrian accused of a crime and killed by a mob on April 23, 1897. The purple signs alerted passersby to Joseph McCoy’s existence and the role his life and death played in our shared history.

We hope that residents and visitors will step into the past and explore the crooked path that traces Joseph McCoy’s last hours. By walking the streets and noting the places where he lived, worked and was likely arrested, we remember a difficult part of Alexandria’s story. After touring the historic Black neighborhood, known as the Bottoms, travel to Market Square and see the police station where Joseph first learned about the charges he faced, which he denied, before eventually confessing. The young Black man twice experienced intense fear as an enraged white mob came after him with murderous intent. Finally, share his last terrified steps to Cameron and Lee Streets. There, honor him by saying his name, acknowledging Alexandria’s history of racial terror and promising to work to ensure a just future for all people.

This guide follows the last six hours of Joseph McCoy’s life chronologically, which zig zags geographically. Please review the map to choose a path, based on ability. The entire walk may take up to 2 hours.

Download a copy of the Guide.

ALLEGATION

Stop Number 1: Dr. O’Brien Medical Office

Sign at 900 Block of Cameron Street

“The father of Annie Lacy took her to Dr. O’Brien yesterday, who found her to be suffering from a specific disease. -Alexandria Gazette

Dr. Mathew O’Brien practiced general medicine on the 900 block of Cameron Street. On Thursday evening, April 22, around 6 p.m. Richard Lacy brought his eight-year-old daughter, Annie to see the doctor. She had been complaining of “feeling badly,” and though a doctor proscribed something days earlier she was growing worse. When Lacy returned home from work, his wife, Mary asked him to take Annie to see Dr. O’Brien, according to news accounts.

The Lacys had three daughters ranging in age from seven to 13, they also had a four-year-old son named James. Annie was the middle daughter between Nettie, who was older, and Lizzie.

After examining Annie Lacy, Dr. O’Brien asked her father if he “thought his child had been tampered with and he replied in the negative.” Some newspapers said Dr. O’Brien questioned the child and secured the information used to accuse Joseph McCoy, others wrote that Lacy interviewed his daughter. All accounts describe Annie as being “reticent,” “pressed,” and “reluctant.” The Evening Star account stated, “Dr. O’Brien had no sooner seen the case than he told what caused it. The little girl was pressed to tell who had done the fiendish deed, and it was then found out for the first time that McCoy had committed the heinous offense of rape.” The Alexandria Gazette added, “A malignant growth had to be removed.” And The Washington Post reported, “He [Lacy] closely questioned his little daughter about the affair. She was reticent and reluctantly told the story of the outrage.” The Washington Post article provided a description of multiple attempts to assault Annie that ended two weeks earlier when she was attacked inside an old kiln at the busy brickyard near the Lacy house. Annie’s sisters witnessed the crime and were alternatively threatened and paid to stay quiet, depending on the account. Several newspapers, most of which were written after the lynching, claimed Annie’s siblings were also assaulted by McCoy.

Dr. O’Brien hailed from Baltimore, Md., attended the Medical College of Ohio, and graduated in 1876. He practiced in Ohio for about 10 years before moving to Alexandria where he became a trusted physician among the white community.

HOME

Stop Number 2: McCoy Family Home

Corner of Wolfe and S. Alfred Streets

Joseph and John McCoy were raised by their Great Grandmother Cecelia McCoy and their Aunt Rachel Chase Gary (Geary, Gray) in The Bottoms, a historically Black neighborhood in Alexandria. They lived in a small wooden house at an address that no longer exists, but once stood at 491 S. Alfred Street, near the corner with Wolfe Street. Joseph H. McCoy was born in 1879 and his younger brother John McCoy arrived in 1882. Their mother was Harriet Chase, daughter to Cecelia’s daughter Ann and Samuel Chase. Joseph’s father was George McCoy, a resident of D.C. who may have been a distant relative of Harriet’s – there are no records of a marriage. In 1883, Harriet married Jarret Green, moved to Pennsylvania, and left her two boys with her grandmother. George McCoy married Amanda Pindell in 1899 and did not appear to play a role in either boy’s life. In 1895, when Joseph was 16 and John was 14, Cecelia died. The Alexandria Community Remembrance Project’s Genealogist Char Bah believes that Harriet’s sister, Rachel raised both boys. After a white mob killed Joseph, Rachel, Samuel and John moved to Washington, D.C. near Charles Chase, who was Rachel and Harriet’s brother.

ACCUSER

Stop Number 3: Richard Lacy Home

800 S. Washington Street

Joseph McCoy worked for Richard Lacy near this site and, according to the Washington Times, McCoy “was regarded as trustworthy.”

By 1891, Richard (Tobe) A. Lacy (Lacey), who grew up near Mount Vernon in Fairfax County, was renting this property across from St. Mary’s graveyard and next to the vibrant Alexandria Brick Company, an area referred to as Bromilaw Point. In 1897, this was where Alexandria blurred into Fairfax County.

Richard Lacy was the second boy born into a large farming family that lived near Mount Vernon. His wife Mary Grimsley’s family was from Accotink, currently located at Fort Belvoir. Lacy bought the property at 800 S. Washington St. in 1895, shortly after he inherited money from his father’s death. In news accounts, Lacy was described as a contractor. He hired Joseph McCoy to assist with tasks such as cleaning, cutting firewood, maintaining the stables and caring for the horses.

At least two newspaper accounts of the lynching indicate that Richard Lacy “took on” or hired Joseph McCoy at an early age, The Washington Times wrote that McCoy had been employed “almost continuously since his infancy” and The Washington Post stated McCoy had been working for Lacey for 16 years. Both papers were trying to establish that there had been a long and trusted relationship between the family and McCoy. But the Lacy’s were not living in Alexandria when Joseph was very young, as late as 1889 they were living in Fairfax. Unfortunately, the 1890 Census was lost in a fire. However, a newspaper article from March 1891 about the death of James Rash of Accotink - who was working for Lacey at Bromilaw Point indicates Lacy lived at 800 Washington Street. In 1891, Joseph McCoy would have been around 12 years-old. At that time, Lacy did not yet have any male children. This was the earliest McCoy could have been associated with Lacy, but it is more likely that he hired McCoy in 1894, when he took on a contract with Fairfax to “rebuild the approaches to the Hunting Creek Bridge.” McCoy would have been around 15 years-old at the time. McCoy’s Aunt Rachel, who was most likely caring for him, lived very close to the Lacy property.

There are two accounts of Joseph McCoy’s arrest, one of which, took place at this location:

Lt. James Smith arrested Joseph McCoy on April 22, 1897. During an interview that was part of an investigation by the Commonwealth of Virginia into the lynching, Lt. Smith claimed that after learning of the accusations against Joseph McCoy, he came to the Lacy home and found the young man chopping wood. Smith stated that he did not tell McCoy he was under arrest or that he was accused of a crime, but implied McCoy should go to the police station with him to keep the young man safe.

ARREST

Stop Number 4: Home of Aunt Rachel

Sign Location: 700 Block of Franklin St.

The police found McCoy at the home of his Aunt Rachel in Muire’s Alley and took him to the police station. When Mr. Lacy learned McCoy “had been captured, he became greatly excited, and ran to his house evidently with the intention of securing a revolver.” -The Washington Times

The alley no longer exists in the spot it did in 1897 where Joseph McCoy’s Aunt Rachel Chase Geary (Gary, Gray) lived at No. 4, Muire’s Alley with her husband Samuel. Their home was located behind a house at 714 Franklin Street where a relative of Samuel’s resided. Rachel was Joseph’s aunt and was likely raising him and his younger brother John. One newspaper, The Washington Times, reported that after learning of the accusation against Joseph McCoy, Lt. Smith found the young man at his aunt’s house and arrested him. Because this paper published this information before authorities developed a cover story we believe this is where Joseph McCoy was arrested.

The morning edition of The Washington Times, that went to print after the crime became known but before the lynching, carried the following story of the arrest: “When the horrible truth was discovered this evening, the father immediately went in search of McCoy, and would doubtless have killed the negro had he been able to find him at that time. The occurrence was reported to police headquarters about 7 o’clock, and Lt. Smith went immediately in search of the negro. He found McCoy at the home of his aunt, in Muire’s Alley, near the scene of his brutal crime. As soon as Mr. Lacy learned that the negro had been captured, he became greatly excited and ran to his home evidently with the intention of securing a revolver. The officer in the meantime hurried to the police station with his prisoner."

INTERROGATION

Stop Number 5: Station House

126 N. Fairfax Street

This is where Joseph McCoy learned he was arrested for criminal assault before being interrogated by police. The Evening Star reported, “At first, he denied everything but after a little persuasion he confessed the whole truth.” -Evening Star

The Station House was located on the east side of City Hall. Today, the faded words etched above what was an entrance to the police station can still be seen. Joseph McCoy spent his last hours alive in a cell in this building. This is where he reportedly confessed to assaulting Lacy’s daughter to Lt. Smith and John Strider, a reporter for the Washington Times and a city councilman.

The Washington Times exclusive stated, “McCoy was taken from his cell tonight and carried into the private office of Chief Webster by Lt. Smith. At first, when questioned about the charge made by the two little girls, he protested his innocence and declared that he had never attempted anything wrong. He finally, however, broke down and acknowledged that he was guilty of the crime charged against him. The details of the negro’s confession, which were given in the presence of a Times reporter, are too revolting for publication.”

After McCoy’s arrest, The Washington Post wrote, “A little later, he was visited by the Lieutenant and Mr. John Strider to whom he made a full confession, giving all the details of the crime.”

Around 8 p.m. Joseph was charged with a felony. Soon after, Commonwealth Attorney Leonard Marbury arrived at the station to officially record McCoy’s confession. More reporters were invited to hear the confession. It is likely Joseph asserted his innocence again to Marbury because the Evening Star, wrote, “At first he denied everything, but after a little persuasion he confessed the whole truth.” The Star also stated that when Joseph confessed he did so “without feeling or knowledge of the seriousness of his crime.”

The details of McCoy’s confession quickly spread throughout Alexandria and “excited groups of men gathered on the street corners” near the police station.

ATTACK

Stop Number 6: Station House

126 N. Fairfax Street

“Two desperate assaults were made on the station house, and leading business and professional men urged the crowd on. Four of the leaders of the first assault were arrested but were released by the mayor of the city after the lynching, in obedience to the clamor of the throng.” -Washington Post

The first attempt to lynch Joseph McCoy occurred shortly after 11 p.m. on Thursday, April 22. A crowd of around 150 people had gathered outside the police station. Lt. Smith addressed the mob telling them the police were prepared to protect the prisoner and advising them to “let the law take its course. If the negro [sic] is guilty, he will be hung all right.”

After the policemen filed inside and shut the doors, an “unidentified man” roused the crowd and urged them to “protect your daughters and sisters.” Several men struck the double doors with a large piece of timber stolen from a nearby lumber yard. The doors swung open to a spray of bullets. “Fire,” ordered Lt. Smith and officers again shot purposefully above the heads of the clamoring crowd. Police apprehended the rioters who had made it inside. The doors were shut, timber wedged against them as a brace and a make-shift barricade was erected. The would be lynch mob outside slimmed as a number of people lost courage.

The four men in custody included a member of the Alexandria Light Infantry and future policeman, and a leading merchant who was also an Alderman. The Alexandria Gazette reported that Richard Lacy was among those detained after the attack. No other newspapers corroborated this information. It was more likely they reported it to provide Lacy with an alibi.

Officer Knight later testified under oath that all four of those arrested were released before a second attempt to lynch McCoy, upon the promise they would “go home and stay there."

MAYOR THOMPSON’S HOUSE

Stop Number 7: Mayor Thompsons House

Sign Location: Corner of Wolfe and S. Fairfax Street

“Constable William Webster said that he was in the station house when the first attack was made, and when the crowd was repulsed he went to the residence of Mayor Thompson, whom he informed of the fact, and at the same time asked for the release of the four young men who were forced into the station house by the mob.” -Washington Post

In 1897, Mayor Luther Thompson lived in a house near this location on the 500 block of S. Fairfax Street. He was both an editor at the Alexandria Gazette and mayor. Because of his position as Alexandria's Chief Executive, Thompson had a telephone in his house for emergencies. After the police thwarted the attempt to lynch Joseph McCoy, they tried to call Thompson, but no one answered. Finally, at around 12:15, Constable William Webster walked to the mayor’s house and knocked on the door. Again, there was no answer. The officer was persistent and eventually, a second-floor window shuddered open. Thompson asked what the Constable wanted. Webster described the attempt to lynch McCoy, the arrest of several rioters and asked the mayor for instructions. In an interview that was part of the Governor’s investigation into the lynching, Thompson claimed he instructed the constable to “Notify Capt. Bryan of the Light Infantry immediately if you anticipate any trouble,” and then he said he went back to bed.

The Mayor could have summoned the largest military company in the state to defend the rule of law, he could have moved Joseph McCoy to a new location or added more police to protect him, he could have gone to the police station to ensure it was secure. Instead, the mayor told police to free the leaders of the attack and went back to bed.

Thompson confirmed that he understood the prisoner was supposed to be protected while in custody, and when asked by the investigator why he didn’t go to the scene to “investigate the condition of affairs,” Thompson said he believed “there was no danger of any violence …whatever.”

The Chief of Police, and father of Constable Webster lived less than a block away. It is likely the officer alerted his father, because the Washington Times, reported, “Chief Webster anticipated their (the lynch mob) return and collected his full force at the jail, there to await the return of the mob.”

ATTACK

Stop Number 8: Station House

126 N. Fairfax Street

“McCoy was cringing in one corner of the cell, almost tied in a knot. The mob did not see him. They thought they had got into the wrong cell. They looked again and found him.” – Richmond Planet

At 1 a.m. Friday, April 23, at least 500 people had collected outside the police station ginned up on rumor and innuendo, many imbibed spirits filling themselves with liquid courage, vinegar and spite. Within the throngs were leading citizens, a few of whom attempted to call off the vigilantes, but most participated and some urged on the mob. Joseph McCoy would have heard their hollering. He would have felt the rage they directed toward him as he listened to the low rumbling roar of hundreds of blood thirsty voices.

After officers refused to give McCoy to the mob, they surged forward, smashing shutters, chopping window sashes, hacking at the building with axes, sledges, crowbars, and picks. The heavy double doors heaved and gave way and bullets whirred and snapped above the sea of heads as police tried to drive back the rioters. Joseph hid in a crevice above the door of his cell.

The lynch mob was led by a short man who wielded an ax. With his help, they broke through the final door that led to the prisoners. When they didn’t see McCoy, they ran upstairs fearing he had escaped. Unable to stay tucked into the wall any longer, Joseph jumped down and slid under a wooden bench in the corner of the cell. Someone yelled, and then what seemed like a million hands clutched the young man’s shoulders, hair, shirt collar, and arms. They dragged him through the corridor, past the chewed-up double doors and dumped him onto Fairfax Street.

ABDUCTED

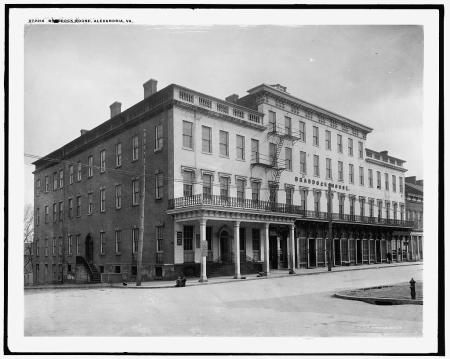

Stop Number 9: Braddock House

121 N. Fairfax Street

“When the mob got him in front of the Braddock House, they held a consultation as to where they should hang him.”

Evening Star

Joseph McCoy had been dragged from his cell and was on his knees in the middle of Fairfax Street. He was surrounded by white men, many whom he knew, and he begged for his life. Sweat, blood and tears ran together blurring his vision as he pleaded. The mob, deep in deliberation over the best place to hang McCoy, didn’t hear him.

TERRORIZED

Stop Number 10: Cameron Street

Sign Location: 200 Block of Cameron

“They carried him down Cameron Street on the run, and for a moment it was thought that he had escaped, and another howl was sent up.” - Evening Star

As the lynch mob marched down Cameron Street toward Lee, they beat Joseph with clubs “almost to insensibility.” He stumbled and fell beneath the crowd disappearing from sight. In the brief respite, Joseph’s tormentors walked past him. Then some thought he had escaped and a screeching howl forced the mob to halt, hands sought him and found him. The parade commenced. Afraid he may get away, they hastily decided to hang Joseph from a lamp post on the southeast corner of Cameron and Lee Streets.

LYNCHED

Stop Number 11: Lynching site

Corner, 100 Block of N. Lee Street

“Before swinging him to the lamp post, some of the mob, in their eagerness for revenge, cut the boy’s throat from ear to ear.” -Washington Times

A rope, pilfered from the awning of Mr. G.E. Price’s shop was made into a noose and looped around Joseph’s neck. A man smashed a cobblestone into his head, he was beaten and burned, sliced and shot. Joseph McCoy was jerked off his feet and the crowd broke into a riotous cheer.

“There will be no more outrages on white women in this town,” someone yelled. Blood ran from Joseph’s nose and mouth. His eye was swollen shut.

“Let it be a warning for the future,” growled a lyncher. They left his body hanging, neck unbroken, for at least a quarter-of-an-hour. At 2:30 a.m. the coroner arrived and asked that the body be taken to Demaine’s funeral home on King Street.

NO ACCOUNTABILITY

Stop Number 12: Former location, Demaine’s Funeral Home

817 King Street

A coroner’s inquest held here found Joseph McCoy came to his death “at the hands of parties unknown.” --Washington Post

By 7 p.m. on Friday, April 23, 1897, at least 100 people had gathered outside of Demaine’s funeral home at 817 King Street. They fanned across the intersection eager to hear news about the Coroner’s Inquest that was being held inside. Dr. William Smith reported the following of Joseph McCoy’s death: “resulted from strangulation. There was a burn on his face as if from gunpowder and it was considerably swollen. There was a large open wound just above his forehead and a contusion on the back of his head. Witnesses had cut away the flesh from the skull and found no fractures beneath these injuries. There were also three gunshot wounds on the left side of the breast. None of these wounds was sufficient to cause death.”

Police officers described a night of chaos and darkness in the hours and moments preceding the lynching. They said they didn’t recognize anyone and suspected that strangers to Alexandria were involved.

After 30 minutes of deliberation, the all-white jury, led by Alexandria Alderman Brill, reached the following verdict:

“We the jury, from the evidence, find that the deceased, Joseph McCoy, came to his death from strangulation at the hands of parties unknown to the jury, and further find from the evidence produced, that the officers of the police force did all in their power to protect the prisoner.”

The news of the verdict reached the crowd outside Demaine's funeral home and as they learned no one would be held accountable for Joseph’s lynching, fear that the African American community would retaliate spread among them. It wasn’t long before the white community was armed and parading through the streets in a show of defiant force that struck terror into the homes of Alexandria’s traumatized African Americans.

PROTEST

Stop Number 13: Penny Hill Cemetery

700 Block of S. Payne Street

“No claim was made by any of the man’s friends for the body. An aunt of McCoy called at Mr. Demaine’s and after looking at the body said, “As the people killed him they will have to bury him.” --Alexandria Gazette, Apr. 24, 1897

In the essay Exquisite Corpse, Ashraf Rushdy wrote that displaying the tortured and abused bodies of lynching victims was done to reinforce the power white people held over the black community. It had become the custom for the families of the lynching victims to quietly bury their loved one (s). They were more concerned with the spirit of the dead than their body. But in 1889, this changed, and a community of African Americans in South Carolina protested the lynching of eight local Black men by refusing to bury their bodies. More than 500 African Americans lined the streets at the funeral and called on God to burn the town.

“The body, whether buried or left to the elements, had become a symbol of the injustice and barbarism of the white community, the failure of the nation’s founding principles,” according to Rushdy.

Maybe Joseph’s Aunt Rachel knew this story, maybe she didn’t, but she was clearly making a statement when on Saturday, April 24, the only mother Joseph had ever really known marched into Domaine’s funeral home. She bravely bore witness to his broken face, his wounded skull, the bullet holes in his chest and then, she refused to bury her nephew.

“As the people killed him, they will have to bury him,” she said.

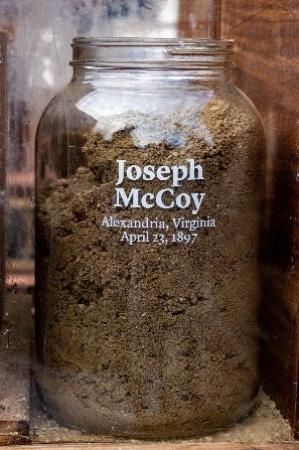

On April 24, 1897 at 3 p.m. Joseph McCoy, 18, was buried at Penny Hill cemetery.

Reflect and Remember

Please take a moment, at the place where Joseph McCoy was buried to reflect and remember. If you identify as white, consider speaking the following Acknowledgement Statement:

I hold the 1897 leadership of Alexandria responsible for failing to protect Joseph McCoy and for failing to prosecute the perpetrators.

I further hold Alexandria’s white community of 1897 responsible for:

- The racial terror torture and killing of Joseph McCoy;

- The terrorizing of the Black community;

- And their actions and inactions on April 22 and 23.

I acknowledge that my predecessors failed this young man, his family, and betrayed their neighbors.

I hope to begin to rectify this past injustice by:

- Giving back Mr. McCoy’s story;

- Telling the truth of our shared history;

- And by committing to a future Alexandria that welcomes diversity and provides equality and justice to all.